Commemorative mass gatherings are a part of Hong Kong’s DNA.

Every year on June 4, tens of thousands of people throng the city’s iconic Victoria Park in memory of those killed in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square Massacre. It is the only part of China where the infamous gunning down of peaceful democracy campaigners in 1989 is even discussed, let alone marked by a sea of candlelit solemnity.

July 1, the day in 1997 that Hong Kong was handed back to China by the British after more than 150 years of colonial rule, has also become a fixture in the city’s political calendar. Thousands use it as a day of protest, to make their voices heard on a range of political issues from LGBT rights to better treatment for migrants workers and ethnic minorities, in a way that would never be permitted in mainland China.

Monday, however, marks a new anniversary in China’s most open city — of its most epoch-making mass gathering yet.

On Sept. 28, 2014, thousands of angry protesters flooded onto the broad sweep of Harcourt Road in Admiralty district — the city’s political heart, being home to the Hong Kong government’s headquarters, the legislature and the local People’s Liberation Army garrison. It was the first time since Tiananmen that so many people had come together on Chinese soil to call for greater political freedom.

What brought them onto the streets was the imprisonment of 17-year-old Joshua Wong, 24-year-old Alex Chow and about a dozen of their student-activist comrades. They had been arrested and subdued using pepper spray after scaling the fence outside the Legislative Council Complex two days earlier, in a symbolic bid to reclaim the square outside it.

Speaking to TIME a year later, and standing just a few meters away from the fence itself, Wong, now 18, calls it “the best decision I made in the past few years.” Without his ascent of the fence and subsequent detention, he explains, the mobilization of the masses for a street occupation that would last the next three months might never have happened.

By the time he returned to Admiralty on Sept. 29, after about 46 hours in custody, nearly 100,000 people had filled the streets, with similar street occupations materializing before the gaze of startled tourists in the city’s popular shopping district, Causeway Bay, and across Victoria Harbour in Kowloon. Tear gas was fired repeatedly by the police against the Admiralty protesters during the night, further inflaming their already heightened passions and prompting thousands more to emerge in a show of solidarity.

“It’s really a picture that I will never forget,” says Wong, the bookish young activist who quickly became known as the most prominent face of the ensuing pro-democracy protests and who was named as one of TIME’s Most Influential Teens of 2014. “It is really one of the elements that motivate me to continue to fight in the future.”

The arrest of Wong and the other students blew the head off a conflict that had been building for a month. On Aug. 31 last year, the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress — the communist government’s rubber-stamp legislative body — handed down a controversial ruling stating that although Hong Kong’s people would be able to directly elect their leader, known as the chief executive, for the first time ever in 2017, only candidates screened and approved by a 1,200-member committee loyal to Beijing would be able to stand for election.

“The decision indicated that China was not prepared to make any concessions, so we had to move on to organize the occupation,” says Benny Tai, a University of Hong Kong law professor who was working independently of Wong and the others.

He originally floated the idea of a civil disobedience movement called Occupy Central With Love and Peace. It was to be a smaller protest — he envisaged around 10,000 people at the most — and it was scheduled, provocatively, for China’s National Day on Oct. 1. But the spontaneous appearance on the streets of more than 10 times that number on the night of Sept. 28, and the surge of support for the arrested student leaders, compelled him to declare an early start to his protest.

“We saw thousands and thousands there — much more than we expected,” Tai tells TIME. “The determination was much stronger than we expected. Even when they faced tear gas and pepper spray, they did not retreat.”

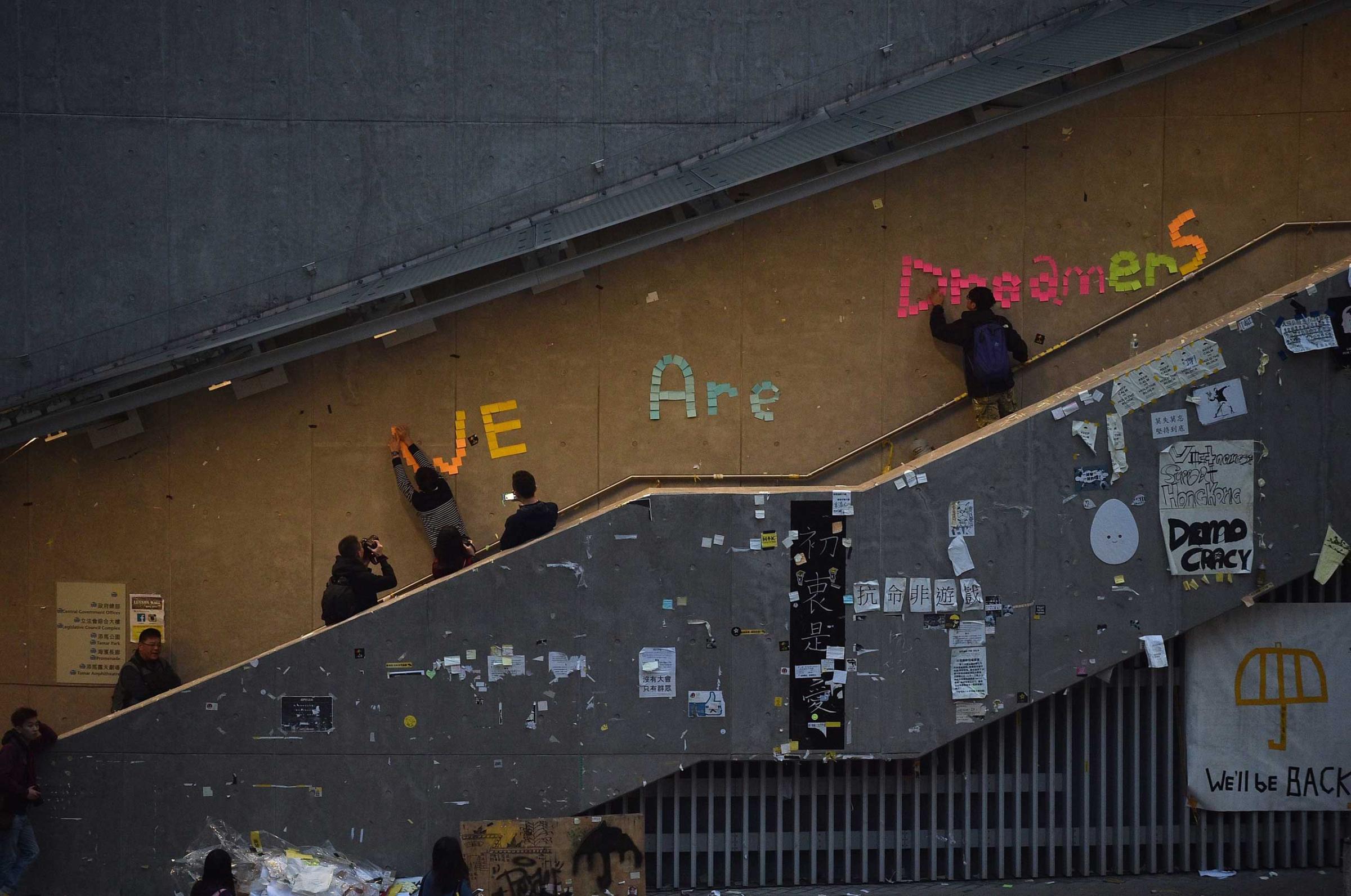

Occupy Hong Kong would go on for the next 79 days, and took on another name, the Umbrella Revolution (or the Umbrella Movement, depending on who you ask), after the umbrellas protesters used as shields against the eye-watering chemicals being sprayed by the police.

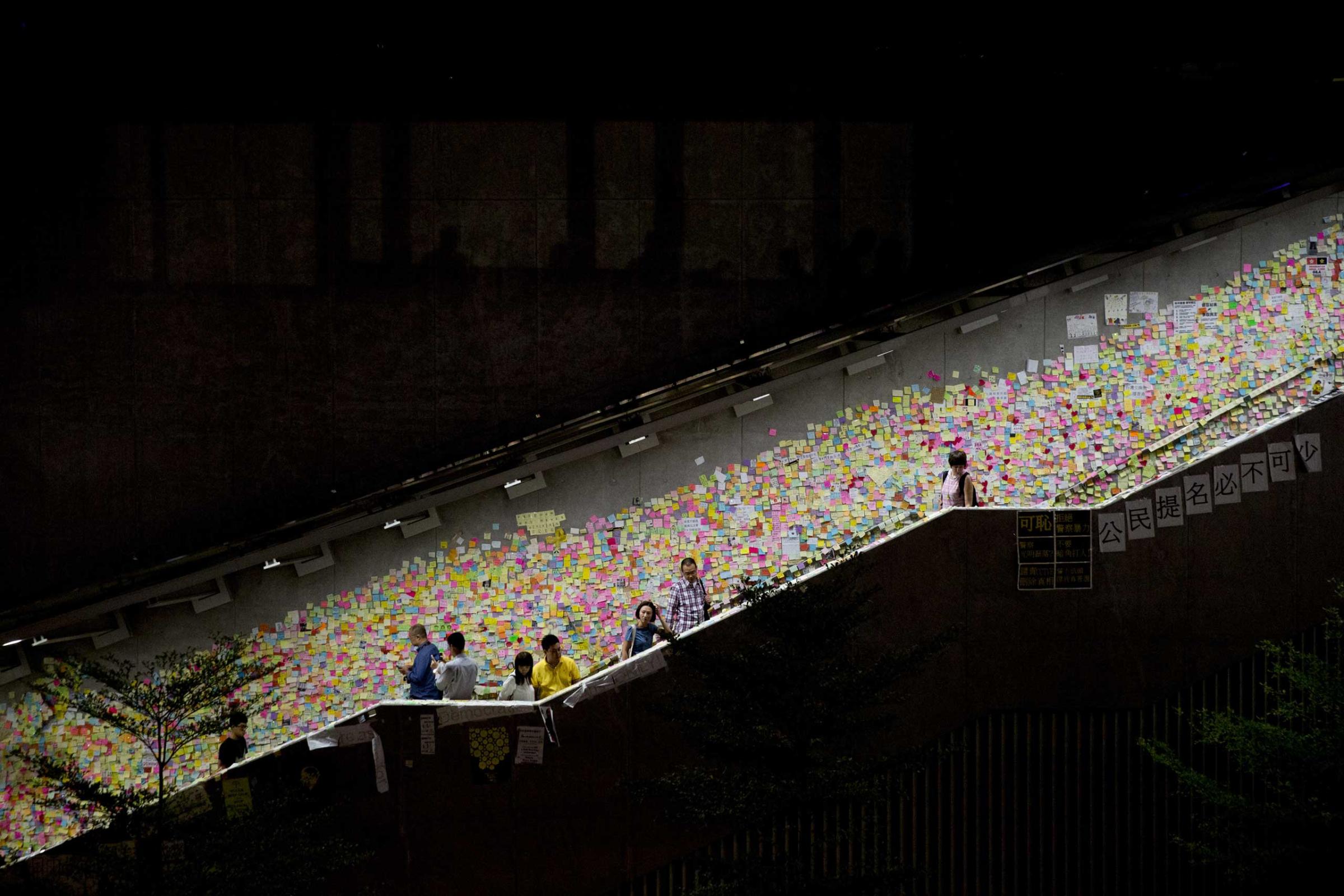

The protesters occupied downtown districts with elaborate tent villages that won international admiration for their peacefulness and order. The largely student inhabitants set up study zones and recycling centers. Volunteers swabbed out nearby public restrooms and kept them stocked with toiletries donated by the public. Artists installed sculptures and outdoor exhibitions. At the Admiralty village — the area was quickly dubbed Umbrella Square — a strip of grass by the side of the road was turned into an organic herb garden. The plate glass windows of expensive boutiques and showrooms, which would have been the targets of stone-throwing anarchists elsewhere, were left unmolested by the polite and well-spoken Hong Kong undergrads. Tourists flocked to the protest sites for photos and office workers, during lunch hour, would take their sandwiches and bento boxes and sit unselfconsciously among the protesters, savoring a city center without snarling traffic or choking fumes.

But as momentous as the protests were, they ended up achieving virtually nothing in terms of tangible results. The main demand of the protesters — a revision of the 2017 election rules — fell on deaf ears in Beijing, while current Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, seen by opponents as a servant of China’s authoritarian government rather than of the people he was appointed to lead, remains in power despite widespread calls for his resignation.

After almost three months without result the protests began to lose steam, popular support and direction, and were unceremoniously and anticlimactically cleared in mid-December.

Protest leaders like Wong and Tai, however, say that even if their immediate aims were not achieved, the Umbrella Revolution brought about the political awakening of a generation.

“The ruling class has dominated the future of the new generation,” says Wong, who is still three years shy of being able to contest political office and is just about eligible to vote. “If we hope to decide our future ourselves, the first step for us to do is to … get more bargaining power.”

Tai says many people who were somewhat “wishy-washy” about politics are now more committed toward the goal of genuine democracy.

“A lot of Hong Kong people have been changed by the Umbrella Movement, and it’s not limited to the younger generation,” he says. “They are transformed.”

The big question, now, is how this vibrant metropolis, with its millions of politically sophisticated citizens, cements its place in a 21st century China that seems only interested in exerting more control. Nobody seems to have an answer.

Holding Out for Genuine Democracy

Hong Kong is governed by a miniconstitution called the Basic Law, drafted during the run-up to the handover of sovereignty. It outlined that it would be returned to the Chinese government as a “Special Administrative Region” under a principle known as “one country, two systems.” This means that Hong Kongers supposed to enjoy a more open economy and far greater freedom of speech than their counterparts in mainland China. It also promises a “high degree of autonomy” and eventual “universal suffrage.” The problem that lies at the root of the pro-democracy movement, however, is that Hong Kong and China define those two terms extremely differently.

“It’s not as if you just call anything universal suffrage — you cannot treat people as if they are all damn fools,” says Hong Kong lawmaker Emily Lau. “It’s more than one person, one vote. It has to have one person, one vote, but in the process the voters must have a genuine choice.”

Lau, chairwoman of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party and a prominent pro-democracy crusader who was also briefly arrested during the Umbrella Revolution, echoes a commonly held belief that Beijing has reneged on its promise to allow Hong Kong a fully democratic election.

“It’s only those who are supported by Beijing, those who are tolerated by Beijing, who will be able to stand, and those that Beijing doesn’t like will not get a look-in,” she says. “So it’s not genuine democracy.”

Despite the widespread public repudiation of the limited voting mechanism put forth by Beijing, the Hong Kong government attempted to enforce it in mid-June this year in the form of an electoral reform bill. However, Lau and 26 other pro-democracy lawmakers from various parties — known collectively as the pan-democratic camp — unanimously rejected the bill in a Legislative Council vote. When they realized that they were four votes short of the two-thirds majority required for the reform to pass, several pro-Beijing lawmakers staged a confused walkout in the hope that it would stall the proceedings, but it did not because voting had already begun. In the end, only eight pro-Beijing legislators were left in the chamber to vote for the bill.

Its failure means that Hong Kong will revert to its previous system of electing the chief executive through a 1,200-member election committee comprised primarily of the city’s pro-Beijing elites, a result many lament as a significant setback for the city’s political progress.

“Even though the political reform package wasn’t ideal, it still meant a step forward in terms of maintaining the democratic momentum in Hong Kong,” Lau Siu-kai, a sociologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and former head of a government think tank called the Central Policy Unit, tells TIME in a telephone interview. “The loss of this momentum is very unfortunate,” he adds.

“Personally I’m disappointed,” says James Tien, honorary chairman of the pro-establishment Liberal Party and one of the eight legislators who had voted in favor of the bill. “I think having your chance for 5 million people to elect the chief executive, even with three candidates screened by Beijing, is better than the current situation.”

That’s not how the democrats see it.

“They want to thrust it down our throats, this electoral reform package, which can do nothing but use our votes to legitimize a vetting process,” says Alan Leong, leader of the pro-democracy Civic Party, in an interview with TIME.

“I’m glad that by vetoing this electoral reform proposal, we are able to keep our dignity,” he adds.

A Bold Call for Self-Determination

Whenever the Hong Kong soccer team takes to the field at home nowadays, a resounding chorus of boos fills the stadium. The fans’ jeers are not directed at the much loved athletes but at “March of the Volunteers,” the Chinese national anthem which Hong Kongers are now supposed to adopt as their own.

China has vehemently protested the practice, and the sport’s governing body FIFA has threatened to impose sanctions that might require the Hong Kong squad to play a November home game against the Chinese national side in an empty stadium.

The spectators’ behavior is just one of the ways in which a long-standing disdain for the mainland and its citizens has manifested itself since the Occupy Hong Kong protests ended late last year.

Weekend protests at shopping malls in Hong Kong-China border areas, directed against Chinese “parallel traders” who buy up essential goods like diapers and milk powder in bulk to resell in the mainland, resumed earlier this month following a six-month hiatus.

A spate of similar protests earlier in the year prompted the government in April to place a limit on the number of weekly visits citizens of Chinese border city Shenzhen could make to Hong Kong. Protests in late June also targeted organized groups of Chinese street musicians singing in Mandarin rather than Hong Kong’s primary language, Cantonese.

Both sets of sometimes violent demonstrations were reportedly initiated by so-called localists — pro-Hong Kong radicals who advocate a spectrum of separation between Hong Kong and China, ranging from greater autonomy to complete independence.

“It will take awhile to counter this sort of negative sentiment toward the motherland on the part of some of our younger people, although I think the bulk of them know that so-called Hong Kong independence is a nonstarter,” says Regina Ip, a pro-establishment legislator and chairperson of the New People’s Party.

Although politicians and analysts are mostly dismissive of the localists and deem their goal highly unrealistic, many of them admit that the larger anti-China sentiment is and should be a concern of the Beijing government. So should the long-term determination of the city’s young.

Student leader Wong, and his supporters, are already stressing the need to look decades into the future — at the year 2047, when the 50-year transition period stipulated by the handover agreement between China and Britain expires. In an essay for TIME, Wong argues that what freedoms Hong Kong has by then will be lost unless they are firmly entrenched in a culture of democracy and autonomy. And the development of that culture, he writes, “involves getting a consensus from both the local and international community that Hong Kongers shall have the right to determine their city’s future.”

He adds: “Hong Kongers should not only focus on universal suffrage, but also fight for the city’s right to self-determination.”

It is a startling call. The communist government has faced calls for self-determination from Tibetans, and Muslim Uighurs in the far-flung region of Xinjiang. But this demand is being made by Han Chinese students in a city rightly regarded as one of China’s great showpieces. It strikes at the heart of the unity and consensus that the central government is so anxious to enforce.

For now, however, most eyes are focused on the 2017 chief executive election. If the incumbent gets re-elected, Occupy Hong Kong founder Tai says, “that will cause more people to feel dissatisfied with the existing system and the tipping point may come.”

If Leung does not come back to serve a second term, however, the attention will be directed toward the next chief executive. The prevailing notion across the political spectrum is that Hong Kong’s next leader needs to strike a firmer balance between making the city’s standpoint clear to the Chinese government and conveying Beijing’s diktats to the people.

The Liberal Party’s Tien, who, despite being pro-Beijing, has been one of Leung’s most vocal critics, says China needs to ensure the next appointee “is not a ‘yes’ man that simply takes orders from Beijing, but is willing to fight for the 7 million people of Hong Kong to express our views to the Beijing leadership.”

The question is whether China will allow an individual like that to assume power.

“Beijing will only choose a particular person as the chief executive only after it has formulated a strategy towards Hong Kong and decided on the role of the chief executive in that strategy,” says Lau of the Chinese University. “A chief executive without Beijing’s blessing is not going to be able to govern Hong Kong.”

Another big question is whether Hong Kong — gradually losing its unique position as China’s financial hub, with so many other mainland cities on the make — will be in a position to push back when the next opportunity for reform comes in 2022.

“When you talk to China in five years or 10 years, do we still have today’s bargaining power?” Tien asks. “Maybe they won’t even give us the same [reform], they’ll give you something less because they’ve moved even further in terms of everything that they want — or because Hong Kong’s contribution will be even less.”

As it asserts its position as the world’s next superpower on the global stage, China will likely be increasingly less receptive to Hong Kong’s demands and more inclined to simply dictate terms.

“When we came to power, we thought we could allay the fears and build a better working relationship with the central government,” says Jasper Tsang, the current president of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council who will end his term next year. “But recently the opposite has been happening — every time we push forward Beijing tightens up, and it’s begun a kind of vicious circle.”

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Rishi Iyengar / Hong Kong at rishi.iyengar@timeasia.com