Before he climbed aboard the rubber raft that brought him to Europe this month, Behzad Habibi, a former translator for U.S. Special Forces in Afghanistan, tried to escape his country the legal way. In his hometown of Herat, he’d received death threats from the Taliban for serving as an interpreter to the American military, and under a U.S. law passed in 2009—the Afghan Allies Protection Act—Habibi felt he was entitled to asylum in the U.S. But his application came up short: He was missing a recommendation letter from a U.S. military officer, and his visa was denied.

He wasn’t alone. Among the thousands of Afghans and Iraqis who aided the American war effort in their countries—usually as translators, drivers or guides—most were left behind as the U.S. forces withdrew. This summer, amid the mass exodus of migrants from the Muslim world, they have gotten a fresh chance to seek refuge in the West. But the U.S. has taken no new steps to accept them, focusing instead on the vast numbers of people fleeing the civil war in Syria.

Since 2011, when the Syrian civil war began, the U.S. has accepted only about 1,500 refugees from Syria, a drop in the ocean of roughly four million people who have fled that country in the last four years. Under increasing pressure from Europe to do more, Secretary of State John Kerry said Sunday that the U.S. would boost its intake of refugees to 100,000 per year by 2017, up from the current yearly limit of 70,000. Kerry made the announcement while visiting Germany, which expects the arrival of more than 800,000 migrants this year, quadruple the number registered in 2014.

To help deal with the influx, the U.S. will focus on finding additional space for Syrians, Kerry told reporters in Berlin. But he made no mention of the Iraqis and Afghans who are also pouring into Europe. Their chances of getting to the U.S. have never been great. Starting in 2008, the U.S. passed a series of laws intended to grant special immigrant visas (SIVs) to the local guides and translators who helped the U.S. in Iraq and Afghanistan. But these laws have been woefully implemented: The U.S. State Department acknowledged in 2012 that out of more than 5,700 Afghans who applied for these special visas, only 32 received them. Many of the others have since turned to far riskier means of escape, and they are not hard to find among the hundreds of thousands of migrants arriving by boat in Europe over the last few months.

Waad Turki-Abed is another case in point. Soon after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, he says he agreed to work for U.S. forces as an informant in Baghdad, divulging the positions of militants leading the fight against coalition forces. Later that year, the Shi’ite militias in the Iraqi capital took revenge against Turki-Abed and his family by murdering his nine-year-old daughter. “They killed her because I worked for the Americans,” he says.

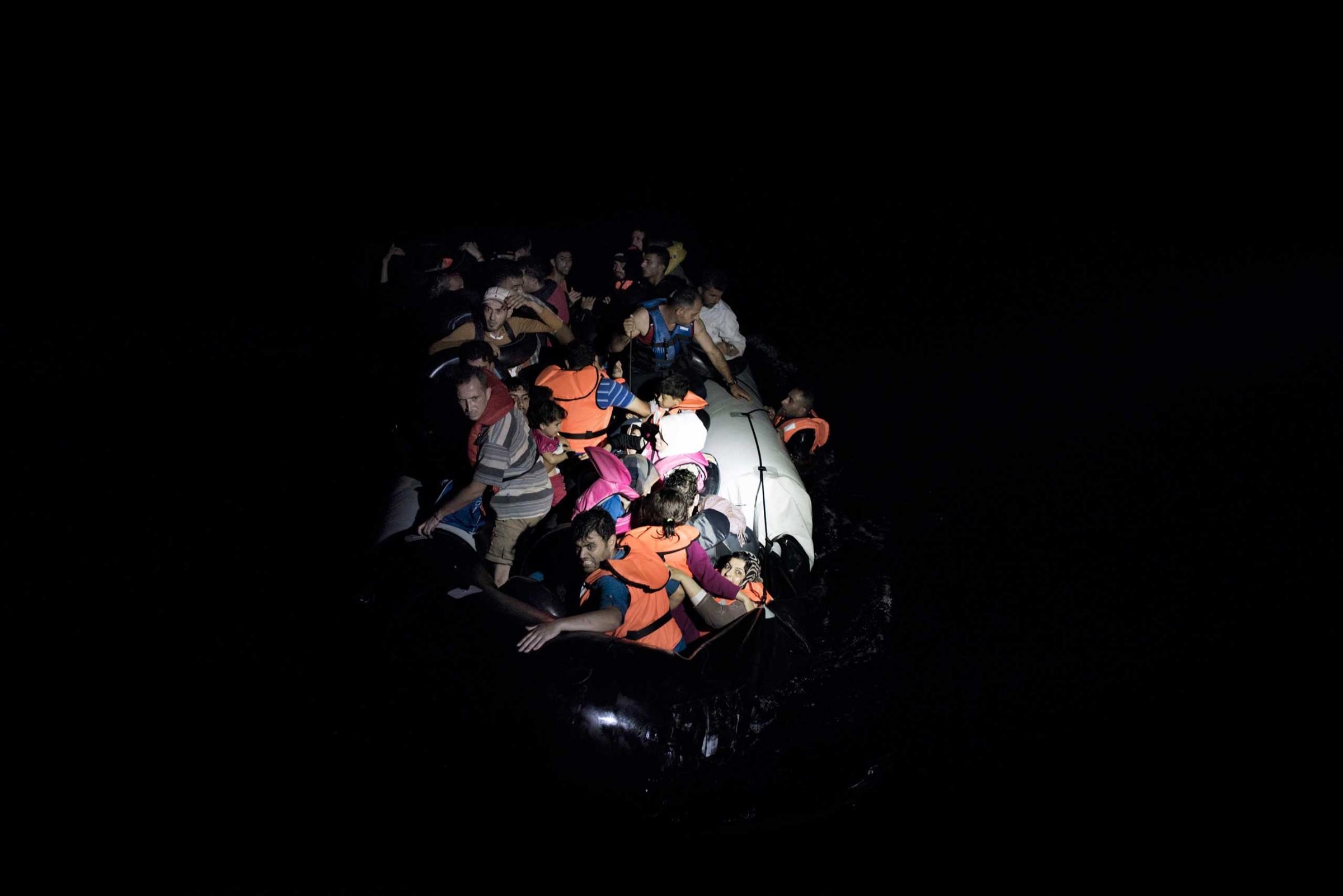

When TIME met Turki-Abed in early September, Greek coast guards had just pulled him aboard their patrol vessel in the Aegean Sea, rescuing him and 46 other migrants from the overcrowded dinghy they were using to cross from Turkey to Greece. Turki-Abed, sporting a greying goatee and a T-shirt that said On The Road, was among the few fluent English speakers among them. He said it was the second time in a decade that he’d been forced to flee his home because of war.

In 2007, as U.S. troops prepared to pull out of Iraq, Turki-Abed fled to Syria with his wife and son, settling in Damascus as refugees. Five years later, a different war came to Syria, and as the fighting intensified around the capital this summer, his 16-year-old son Noor set out on the migrant trail toward Western Europe. He called his parents in Damascus nine days later to say he was about to cross by boat from Turkey to Greece, and then Noor stopped answering his phone. After a few anxious days spent waiting for news, his father set out to find him. “I already lost a daughter,” Turki-Abed said aboard the Greek coast guard vessel. “I don’t want to lose my son.”

Folded and stuffed into his fanny pack is a copy of a letter from the U.S. military command in Iraq, certifying that he worked for the allied forces as a guide. Though his first priority is to find his son along the migrant trail, Turki-Abed, who is 56, says he then plans to present the letter to the nearest U.S. embassy and apply for refugee status for himself and his family. “If the U.S. helps us, then we will go to America,” he says.

These Photos Show the Massive Scale of Europe’s Migrant Crisis

But such pleas for help often run up against U.S bureaucracy. Habibi, the Afghan translator, says it would have been impossible for him to get all the documents required for a special immigrant visa. In 2011, the Taliban came to his home in Herat and threatened to kill him and his family if he worked one more day for the Americans. “My boss, a captain, called me and asked why I don’t come,” recalls Habibi. “I told him I can’t come to work anymore. It’s too dangerous.” Even traveling to the American base to receive the captain’s recommendation letter could have cost him his life, he says.

So he laid low and waited for his next chance to flee, this time illegally. Early this summer, as the tide of migrants heading toward Europe intensified, his parents began scrounging together the money for Habibi to leave as well. The most dangerous part of the journey was also the most expensive: human traffickers charge more than $1000 to bring migrants from Turkey to Greece on rubber boats. But the most difficult part was saying goodbye. “It’s f—ing hard to leave home, leave everything,” he says, his English tinged with the profane vernacular he picked up from U.S troops.

On Sept. 4, when his boat came ashore on the northern coast of Lesbos, one of the Greek islands nearest to Turkey, Habibi said his plan was to make it to Europe for now, most likely to Germany. But ultimately he wants to settle in the U.S. and bring his parents over from Afghanistan. “After all this,” he says, looking around at sea and the boat he had just used to cross it, “the Americans owe me.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com