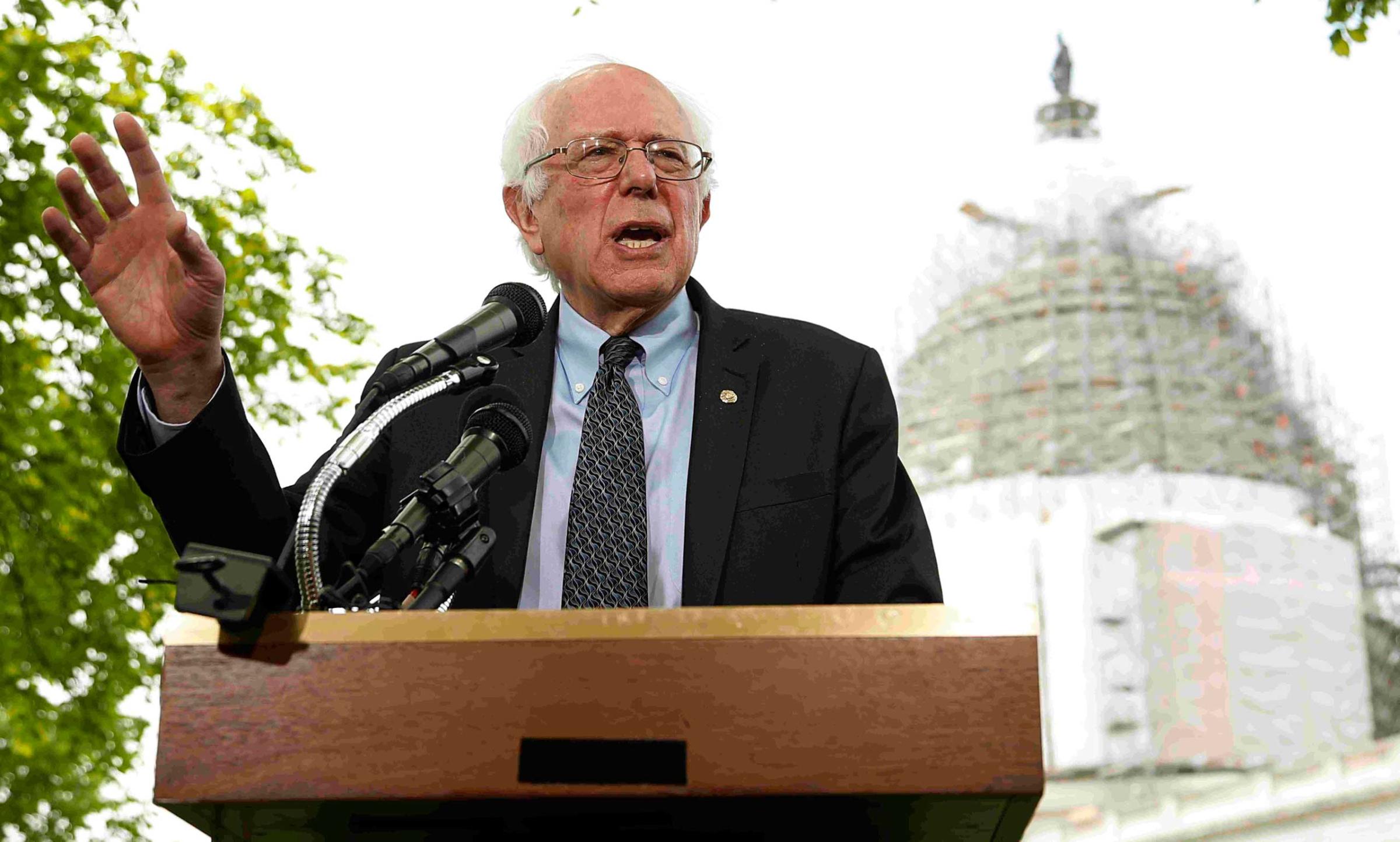

When Bernie Sanders was attacked by a hardened team of political operatives who dished dirt on him to reporters, the Vermont senator sniffed and turned to what he knows best: the moral of the story.

“That’s what negative campaigning is about,” Sanders tells TIME in an interview for this week’s cover story, responding personally to an attack against him by a Hillary Clinton-affiliated super PAC, Correct the Record.

Clinton’s surrogates finally bared their teeth this week and attacked Sanders after months of watching him surge in the polls, linking Sanders in opposition research sent to a reporter with the socialist authoritarian president, Hugo Chavez. The research pointed to a program Sanders negotiated to buy discounted Venezuelan heating oil for low-income Vermonters; Sanders pointed out to TIME that Vermont was the sixth state to do so.

“To connect that to all of Chavez’s views or activities is preposterous,” Sanders says. “I think it’s very unfortunate, and that is the kind of politics that I am trying to change.”

It’s the answer of a candidate who has never played politics like his rivals. The prevailing brand—barbed attacks, research passed to favored reporters in private emails, well-funded research machines—is anathema to Sanders. He has no super PAC and a only a thin staff at his headquarters in Vermont, with little manpower to research dirt on his opponents. This is a strategy Sanders doesn’t know how to employ. Soap opera, Sanders scoffs.

In a traditional campaign year, his would be a losing stance. But in a year of deep disappointment with the political status quo, the usual rules don’t apply. Sanders’ above-the-belt approach reflects the purity of the movement that he is seeking to build, and it’s what has brought crowds as large as 28,000 in Oregon and 11,000 in Arizona. Sanders’ “political revolution”—a sweeping far-left platform that includes universal healthcare, free tuition at public universities, a $15 minimum wage and comprehensive campaign finance reform—doesn’t dwell long on personal slights.

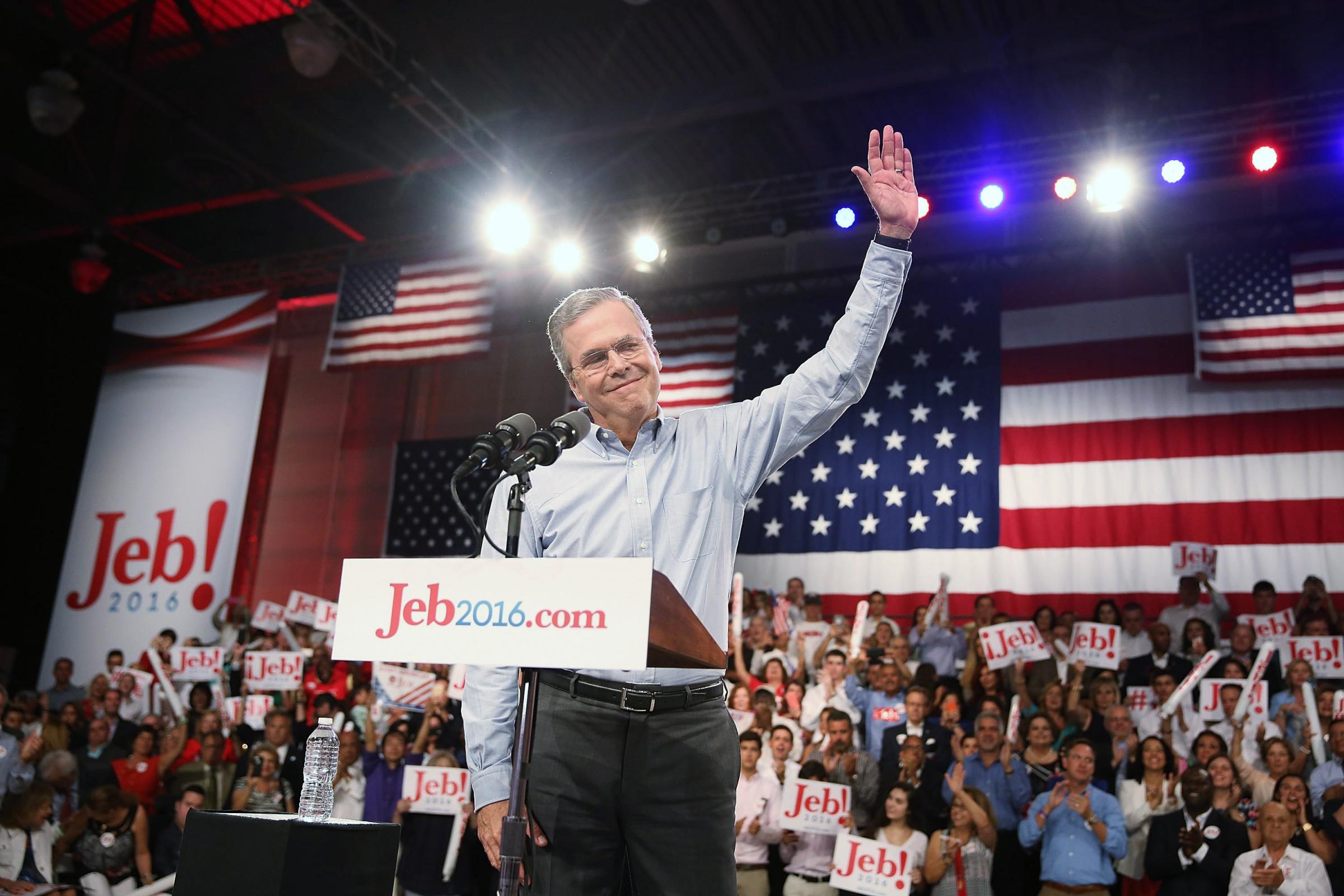

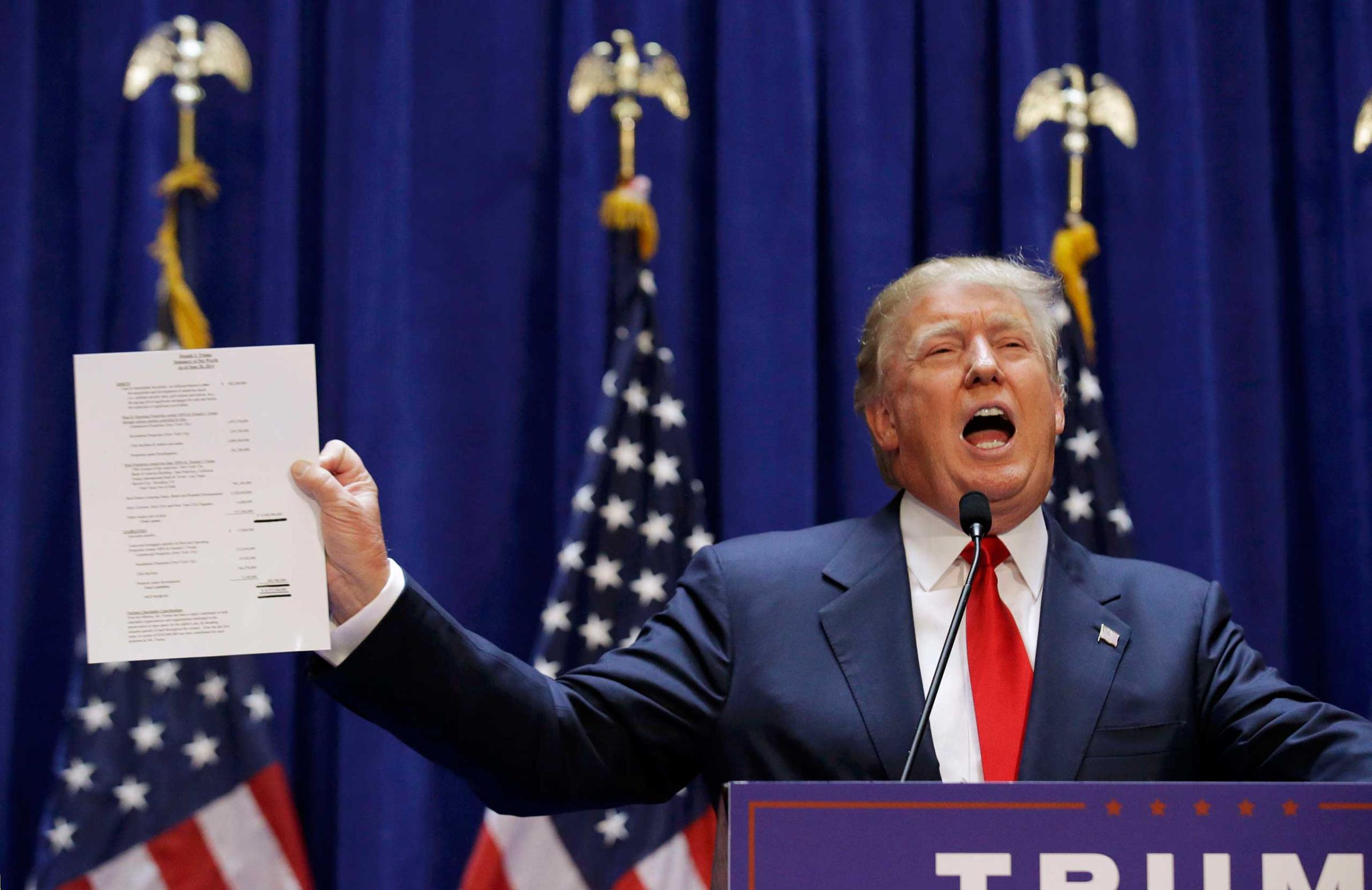

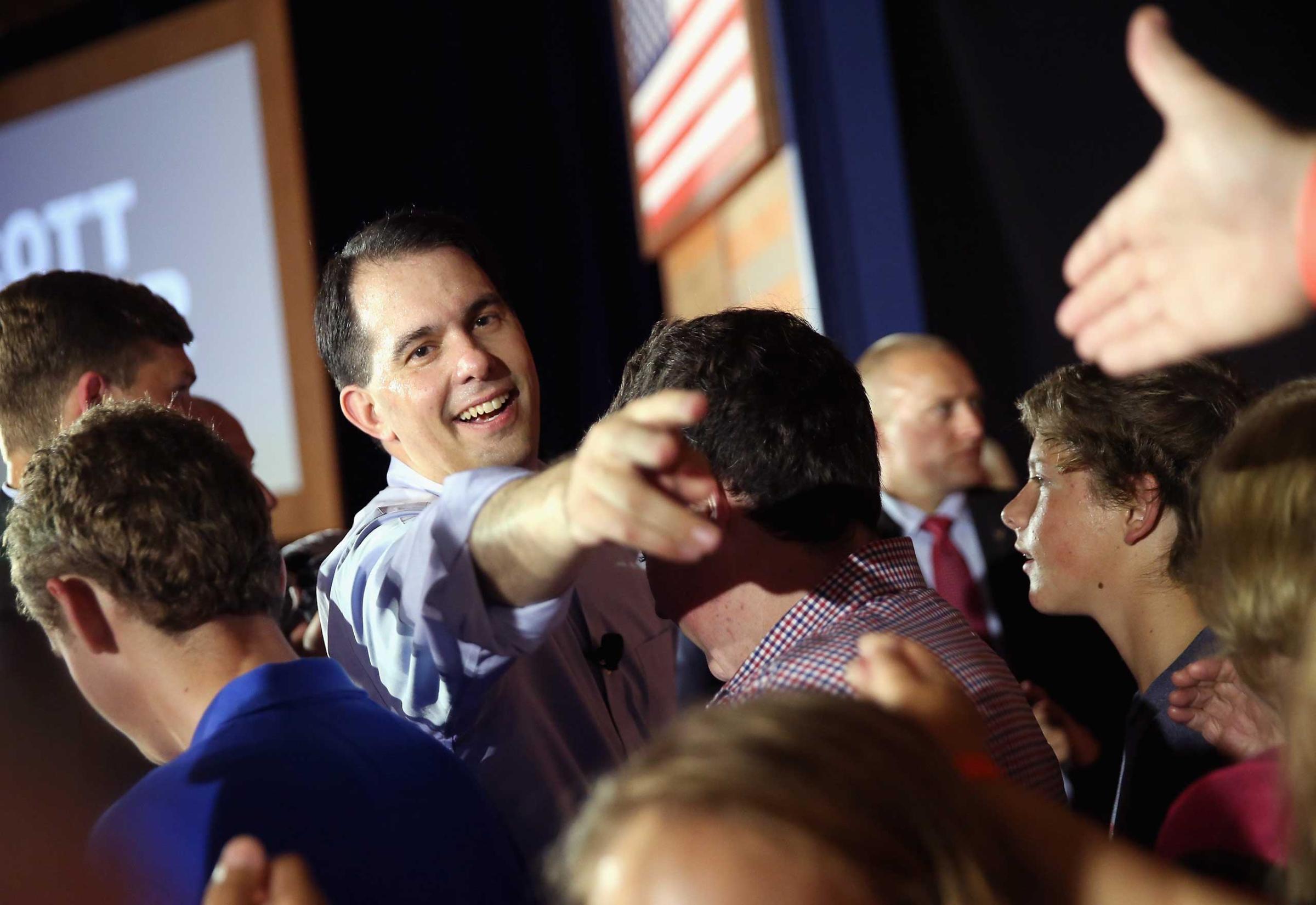

See the 2016 Candidates' Campaign Launches

Some 182,000 people have asked Sanders how they can volunteer, setting up tables in farmers markets, canvassing door-to-door and preaching the word on colleges quads and sports arenas. Stories abound of supporters such as Bob Friedlander of New Hampshire, who left his position as a palliative care doctor to volunteer full time, or Corbin Trent of Tennessee, who sold his food truck business and campaigns full time for Sanders, driving around the state on his own dime.

They say they are attracted by Sanders’ authenticity—pointing to his nearly 50-year-long career as an activist—and his vision, which sounds like a progressive’s Shangri-La: healthcare for all, a trillion-dollar jobs program and big money out of politics.

Most observers say Sanders’ movement is a quixotic gesture, destined to die a demographic mess if he fails to shake Hillary Clinton’s firm support from African-American voters.

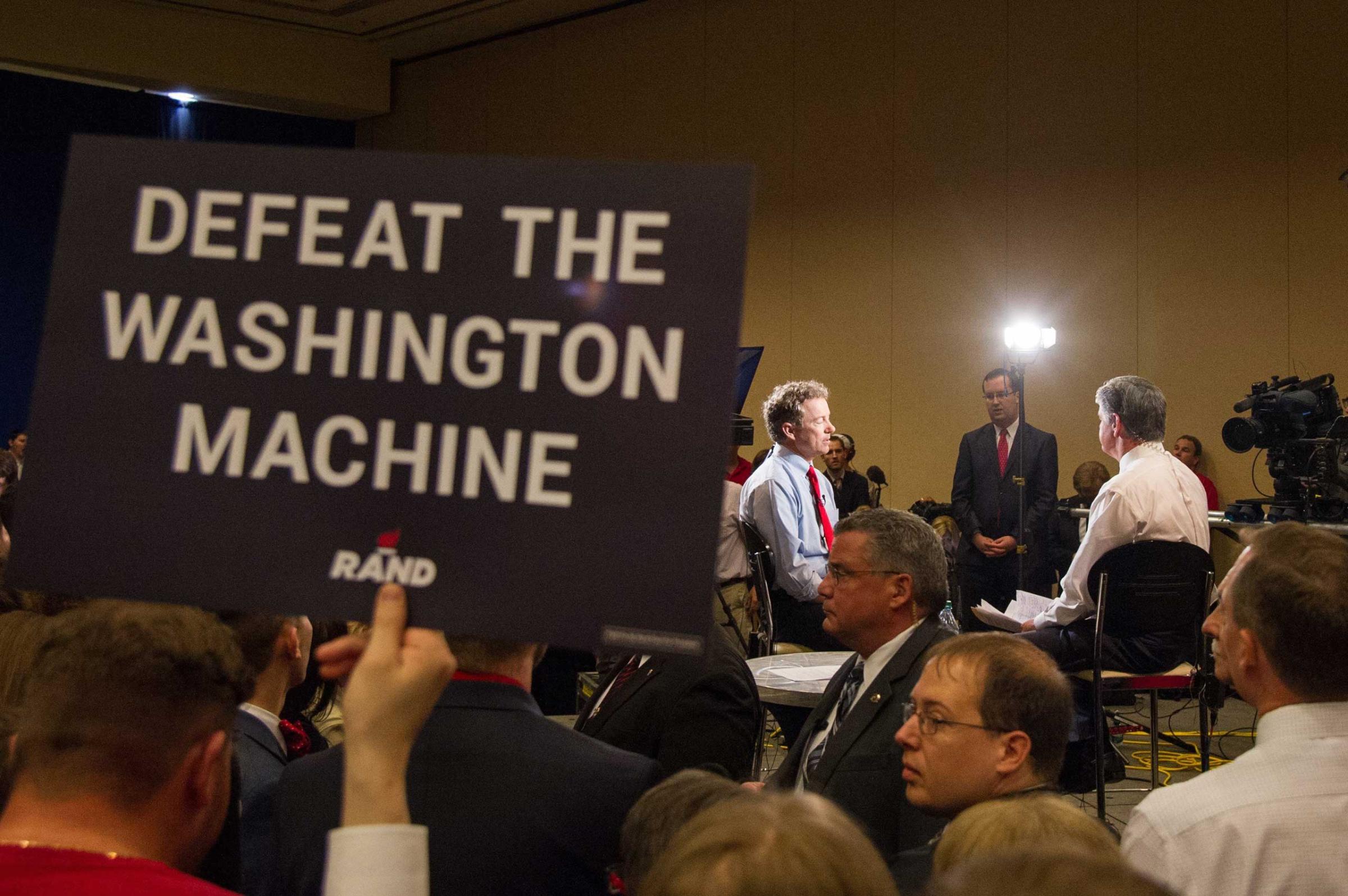

Sanders says his fight is aimed at challenging Washington interests. He sees clearly drawn moral lines, pledging to fight an issue-based campaign that he hopes will mobilize millions. “In this fight we are taking on the greed of the billionaire class,” he tells TIME. “And they are very, very powerful and they’re going to fight back furiously. And the only way we succeed is when millions of people stand up and decide to engage.”

As Sanders surges in the presidential race and overtakes Clinton in New Hampshire and Iowa, he is beginning to draw fire from the frontrunner’s surrogates. Rep. Joaquin Castro, a Clinton supporter, criticized Sanders for not reaching out to the Hispanic caucus in Congress. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo compare Sanders unfavorably to Clinton, and Sen. Claire McCaskill in June suggested Sanders is too liberal to be elected. Clinton has complimented Sanders obliquely, saying he’s done a good job campaigning, but she has not mentioned his name on the trail.

Read More: The Presidential Candidate Who Agrees the Most With Pope Francis

Brock’s super PAC, Correct the Record, is one of the organizations that can spend unlimited sums of money this election cycle thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United. Sanders, meantime, vows to overturn the decision with a constitutional amendment, and he does not have a super PAC.

For his own part, Sanders has not restrained himself in criticizing Clinton’s positions, and he can tick off their differences one by one. “Secretary Clinton and I have very significant disagreements on a number of issues,” Sanders says. “How we deal with Wall Street. I believe in reenacting Glass-Steagall and breaking up these big financial institutions, she does not. Our views on foreign policy will be different. I voted against the war in Iraq and she didn’t.”

“I believe in raising minimum wage nationally to $15 an hour and I don’t believe that’s her positions,” Sanders continues. “I believe we have got to kill this Trans Pacific Partnership, that is not her position. I believe we have got to stop the Keystone Pipeline, she has not made a position on that. I voted against the USA Patriot Act she voted for it.”

Sanders often cites Pope Francis, saying he admires the Pope’s advocacy for the poor and screeds against income inequality. When the Pope visits Washington next week, Sanders will be cheering him on.

“The message to the Pope is: Keep doing what you’re doing,” Sanders says.

To read more of TIME’s interview with Sanders, check out the magazine story here.

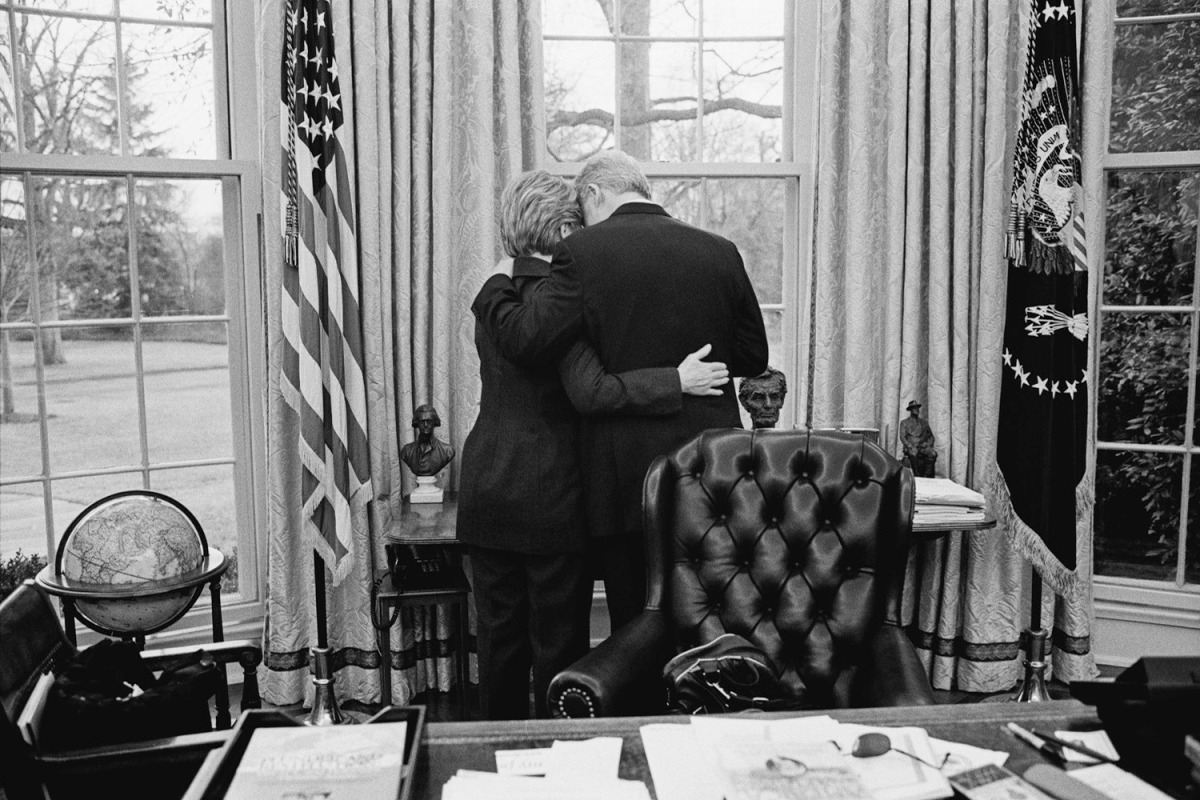

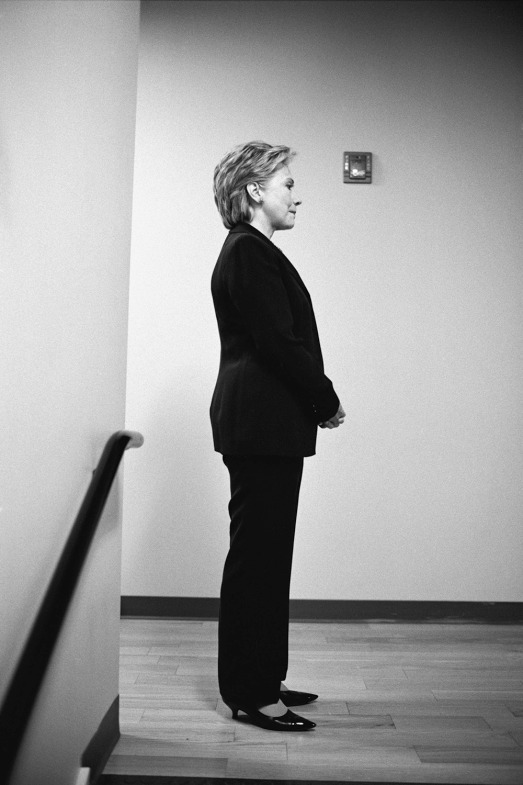

See an Intimate Portrait of Hillary Clinton

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com