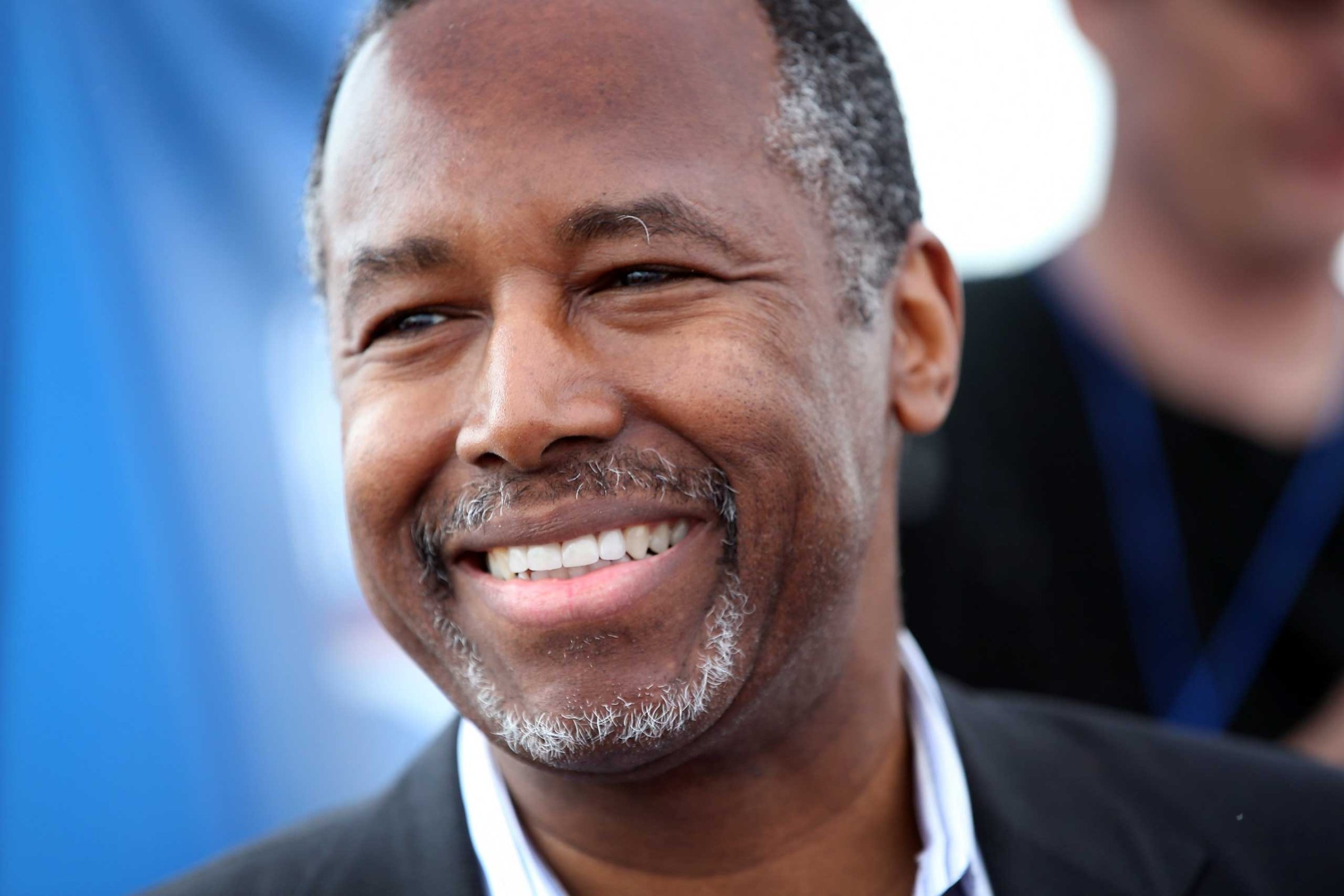

Ben Carson’s Facebook page is filled with animals. One dog reclines by a sign that says “Brownie Barks for Ben.” Grasshopper the rabbit stands by a homemade “Bunnies for Ben” flier. Lucky and Lulu the hamsters sniff around by a “Run Ben Run” sign planted the food in their cage.

Pictures of these pawed supporters are being posted in droves because Carson’s campaign team created a “Pet Week” on their social media accounts, which they say turned their Facebook account into the most engaged political page that week in June. “We’ve had a lot of pets involved,” communications director Doug Watts says of their social media strategy.

The pet strategy wouldn’t fly at most campaigns. But then, Carson isn’t running just any campaign. Everything about his candidacy has been unorthodox from the start, and even his staff are amazed by the outcome. “None of us … have ever seen anything like it,” Watts says. “It’s a different thing than we’re accustomed to with candidates. Usually it’s a hard sell. With Ben, it just really isn’t.”

The retired neurosurgeon recently tied with Donald Trump for first among Republican voters in one Iowa poll with 23% of the vote, and he ranks second nationwide in Republican polling averages. He has also proved himself a veritable fundraising machine, raking in $21.5 million, according to his campaign, with $6 million coming in August alone. As of August 1, he was behind only Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz in hard money totals.

So how has he done it? With a strategy focused on exploiting social media and engaging his supporters from a distance. While other candidates camp out in early primary and caucus states, he has not set foot in Iowa in nearly a month. His campaign has focused almost entirely online, eschewing television ads for direct mail and posts on Facebook. As a result, he has made almost all of his money from small donations of $200 or less.

Carson went from a few hundred thousand Facebook fans at the beginning of the year to more than 2.7 million today. By comparison, Jeb Bush has less than 300,000 likes on his page; Marco Rubio has less than 1 million. (Carson is still topped by Donald Trump, who has 3.6 million.)

Carson’s team says they’ve done this by having fun with Facebook content with things like Pet Week. “[It’s] not all boring and government oriented and politics oriented,” says Watts. But these silly Facebook photos mean real cash for the Carson campaign.

Take, for example, the Healer Hauler. That’s the name of Carson’s new bus, the moniker chosen through an online competition. Carson’s campaign said that if people donated $50, they could get their child’s name written on the side of the bus, “so that every morning when Dr. Carson got on the bus he would remember why he was running,” says campaign manager Barry Bennett. Carson will now see about 4,000 reasons he’s running on the side of the Hauler; his campaign made $200,000 from the fundraising stunt.

Or take the ballot check in South Carolina. To get on the ballot in South Carolina, candidates have to pay $40,000. So Carson’s campaign reached out on Facebook and asked people in the state to donate $40 to help them write the check. They made $160,000 in two days. “If he posts, ‘I’ve scratched my left ear,’ we get 9,000 likes,” Watts says of Carson’s social media celebrity.

Of all the Republican candidates, Carson has the highest percentage of contributions coming from donations of $200 or less. According to his campaign, 97.8% of all contributions have been small dollar amounts, making up 82% of the total haul. Only liberal wunderkind Bernie Sanders makes up more of his contributions from small donations. Of the campaign’s total donations, about 10% come from Facebook asks like the bus and the South Carolina ballot; the rest come from direct mail, online and major donors.

Carson’s team hopes to ride this wave of $50 checks into early 2016 when the primaries start. Campaign manager Barry Bennett says the goal is to win in Iowa (“excellent chance”) and South Carolina (“really good chance”) and get into the top four in New Hampshire, where the voters tend to be less socially conservative. Then it’s on to the South. “We want to be in the top four going into the SEC primary,” Bennett says.

To achieve this, the team is going to avoid spending on television and stick to their small money, social media approach. “You can go out and wave your arms and carry around balloons and try to get on TV and have that kind of attention-getting activity, “ Watts says. “It’s not his style, it wouldn’t fit him at all, and you expend a great deal of effort and get very little return. So we spend a lot of time on the Internet.”

They also plan to avoid any negative campaigning. While other candidates make the headlines by trading verbal barbs, Carson refuses to spar with other candidates, and even if they attack him first. “We made a choice at the beginning of the campaign, when we never envisioned Trump getting into the race, that we were not going to be criticizing, attacking or dealing with any of the other candidates and their campaigns even if assaulted by them, which we expect to happen,” Watts says. “It’s not Dr. Carson, it’s not the way he works.” (For his part, Trump has said, “I like Ben a lot. He’s a good guy.”)

Carson has a staff of 57 spread over 5 states and 34,000 volunteers in all 50 to help him on the ground. The campaign is starting a new fundraising effort with their volunteers that Bennett calls “micro-bundling,” fitting with their strategy of targeting small dollar amounts. Instead of asking volunteers to raise $100,000 for the campaign, they’ll ask college students or others without access to large donors to help them raise just $100 or $500.

The key to the strategy succeeding will be Carson maintaining his support as voters get closer to casting their ballots. Carson has consistently been near the top of the polls. His campaign is confident that these surveys, which often aren’t predictive of the eventual nominee at this point in an election cycle, will count when it matters: “Survey results are votes at that point in time,” senior strategist Ed Brookover says.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Tessa Berenson at tessa.Rogers@time.com