When Ryan O’Leary went to war for the third time, he was expecting to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS), the militant group that has captured vast swathes of Iraq and Syria. After serving with the Iowa National Guard in Iraq in 2007-8 and then in Afghanistan in 2010-11, he went back to Iraq earlier this year of his own volition. The intention, he told the Des Moines Register in June, was to train Kurdish soldiers — the Peshmerga — to drive ISIS out of its northern Iraqi strongholds. “ISIS isn’t just a fight for them,” he said then. “It’s a fight for all of us.”

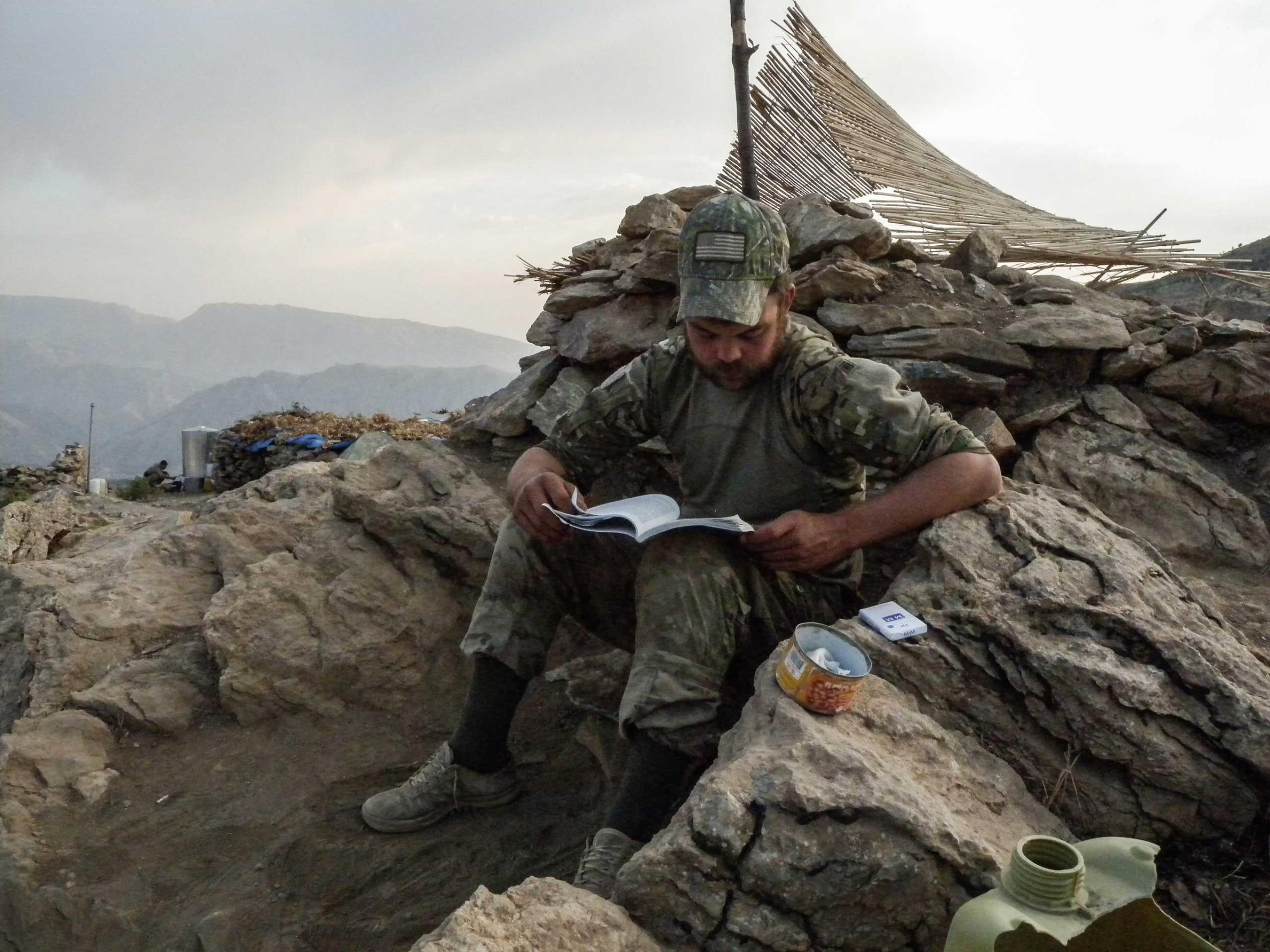

But the 28-year-old’s journey took a slightly different direction once he got to Iraq. Now, O’Leary is patrolling the border between Iran and Iraqi Kurdistan embedded with a faction of the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI) deep in the Qandil mountains. And he’s training the soldiers not to fight ISIS, but Iranian forces he says are repressing Kurdish minorities in the region. “I’ve pretty much changed my view,” he tells TIME in a telephone interview. “There’s no difference between Iran and ISIS, they do the exact same thing to these people. It’s just not reported as much.”

The KDPI is one of several political organizations representing Iran’s Kurds, an ethnic group of about 7 million people living both in Iran and in the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq. The party has been outlawed in the Islamic Republic for decades, as it advocates for greater independence and European-style social democracy. The unit O’Leary is with patrols the mountainous border ostensibly to defend Kurds against Iranian aggression.

So how did O’Leary get involved? He says he felt rootless after returning from Afghanistan in 2011, and itched to serve again in some way despite suffering some symptoms of PTSD. “I felt a bit lost when I got back,” he says now. “I didn’t have a purpose.” A Kurdish translator for his National Guard unit put him in touch with a British former soldier who was training Peshmerga, who gave him some contacts in northern Iraq. Against the advice of his family — and the U.S. government — he flew out in June.

When O’Leary arrived in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, he said he went looking for a Peshmerga unit “that wouldn’t allow me to get babysat.” He met with an official with a faction of the KDPI who convinced him the bigger threat to the region’s Kurds was not ISIS, but Iran. “ISIS isn’t a permanent threat to Kurdistan or even the region,” O’Leary says. “But the influence from Iran in this region is getting insanely huge. It’s a hardline religious view.”

So he teamed up with KDPI soldiers in the border region northeast of Erbil, becoming “basically the first Westerner they’ve ever let in,” he says. He claims to be teaching the soldiers tactics picked up from his own days in the military, using what little Kurdish he has picked up; how to mount an ambush, how to observe troop movements, how to give basic first aid. His trainees aren’t like the battle-hardened Peshmerga, who are fighting ISIS in northern Iraq; there’s no rank structure, and the men can be as old as 60.

Tensions have indeed been rising between Iranian Kurds and the regime in recent months. In May, thousands of Iranian Kurds took to the streets in the Iranian city of Mahabad and elsewhere in a series of sometimes violent protests against the regime. Armed Iranian Kurdish parties threatened to send militia to Tehran if the Islamic Republic wouldn’t grant them autonomy. O’Leary claims Iran has shelled border villages and executed civilians on the border and that Kurdish groups have made raids on Iranian outposts.

He won’t talk about current operations but said the troops he is with are “trying to avoid direct conflict.” Instead, O’Leary says, the focus is on preparing to defend the border during an Iranian incursion he believes will come once the U.S. approves a nuclear deal. Without military sanctions the country will finally feel emboldened to crack down on its rebel minorities, he says. “I think this will escalate to armed conflict, and when it does I’ll be there for it.”

It may not come to that, says Martin van Bruinessen, professor of the comparative study of contemporary Muslim societies at Utrecht University. Although there have been Iranian military incursions into Kurdish areas in the past, he says, the regime has long agreed to forgo military action on the border so long as Iraqi Kurds prevent Iranian exiles from mounting attacks. As for the pending nuclear deal, “the Iranian Kurds are in fact rather hopeful of a liberalizing impact,” he says.

There’s little doubt who is the more serious regional foe, he adds. “The confrontation with ISIS, in which Iranian proxies are playing a significant part and Iran’s influence in general appear to be increasing, represents a more serious threat to the KDPI.”

So what do the U.S. authorities make of a U.S. citizen inserting himself into a decades-old conflict between Iran and its Kurdish minorities? Rasheeda Clements, a spokesperson for the State Department, tells TIME that the U.S. government does not support any U.S. citizen traveling to Iraq or Syria to train soldiers for the KDPI. “Any private U.S. citizens/civilians who may have traveled to Iraq or Syria to take part in the activities described are neither in support of nor part of U.S. efforts in the region.”

O’Leary says he’ll stay in the country until he feels he has made a difference. His goals are to make the international community aware of the threat posed by Iran to Kurdish minorities, he says, and to prepare the troops for whatever fighting there is to come. Finally he has a purpose, he says. “I’m not just out here running around with a gun, I’m trying to change things.”

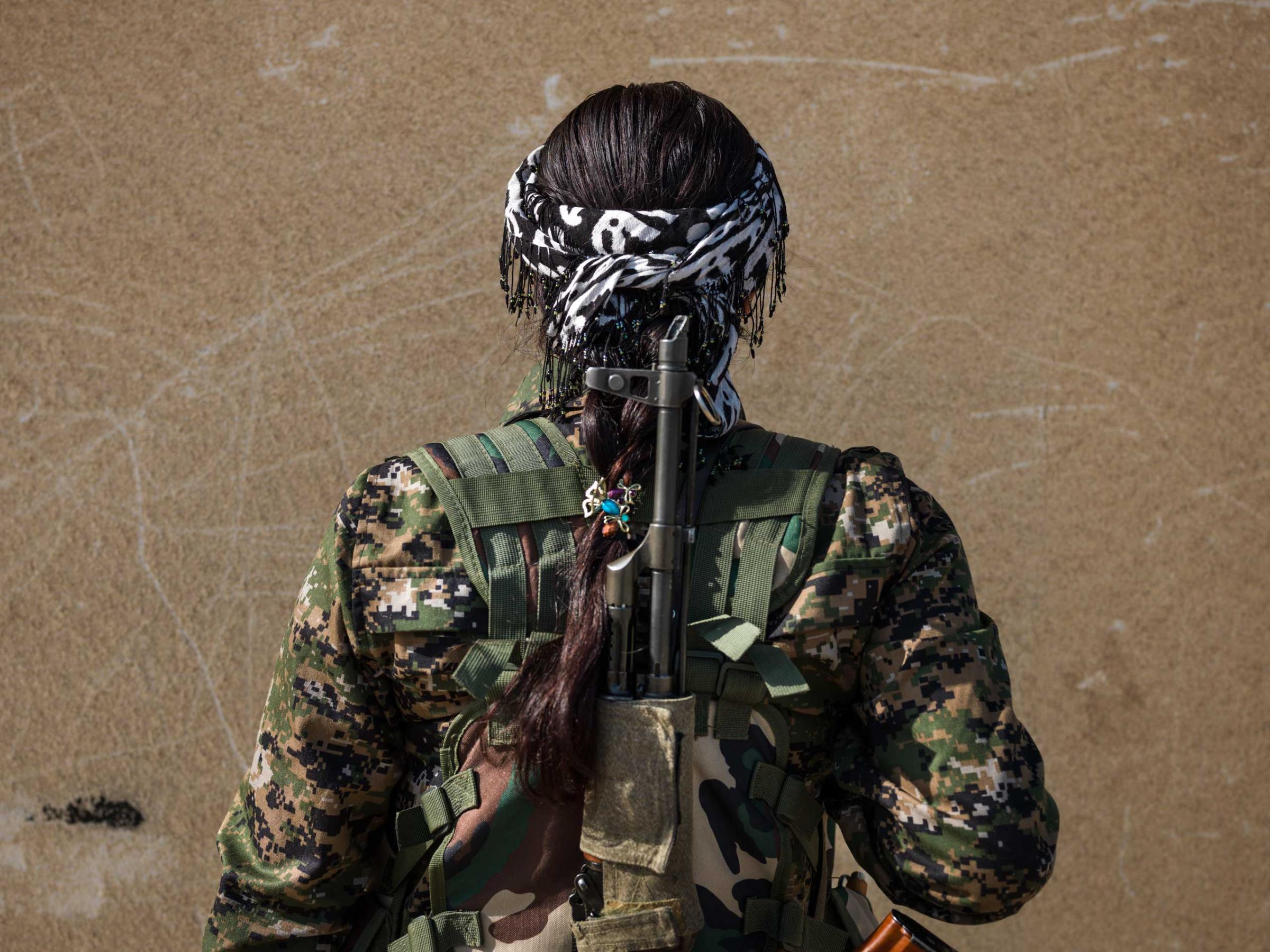

Meet the Kurdish Women Taking the Battle to ISIS

![18-year-old YPJ fighter Torin Khairegi: “We live ina world where women are dominated by men.We are here to take control of our future..I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been matryred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path." Newsha Tavakolian for TIME Zinar base, Syria "I joined YPJ about seven months ago, because I was looking for something meaningful in my life and my leader [ Abdullah Ocalan] showed me the way and my role in the society. We live in a world where women are dominated by men. We are here to take control of our own future. We are not merely fighting with arms; we fight with our thoughts. Ocalan's ideology is always in our hearts and minds and it is with his thought that we become so empowered that we can even become better soldiers than men. When I am at the frontline, the thought of all the cruelty and injustice against women enrages me so much that I become extra-powerful in combat. I injured an ISIS jihadi in Kobane. When he was wounded, all his friends left him behind and ran away. Later I went there and buried his body. I now feel that I am very powerful and can defend my home, my friends, my country, and myself. Many of us have been matryred and I see no path other than the continuation of their path."](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/kurdish-women-fighters-syria-isis-newsha-tavakolian-09.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com