If there’s one company capable of literally breaking the Internet, it’s likely Google, the sprawling giant that provides everything from search results to viral videos and operating software for smartphones and tablets. On Aug. 10, the 16-year-old company did so figuratively, at least, by announcing it would rename and reorganize itself in one of the most unusual moves in Silicon Valley history.

Google–comprising the firm’s best-known ventures including Google.com, Android, YouTube and its advertising businesses–will become a subsidiary of a new umbrella outfit called Alphabet. The latter will be a holding company with far-flung units pursuing driverless cars, life extension, Internet balloons, delivery drones, broadband service and more. “From the start, we’ve always strived to do more, and to do important and meaningful things with the resources we have,” company co-founder and chief executive Larry Page wrote in a blog post announcing the change. “We are still trying to do things other people think are crazy but we are super excited about.”

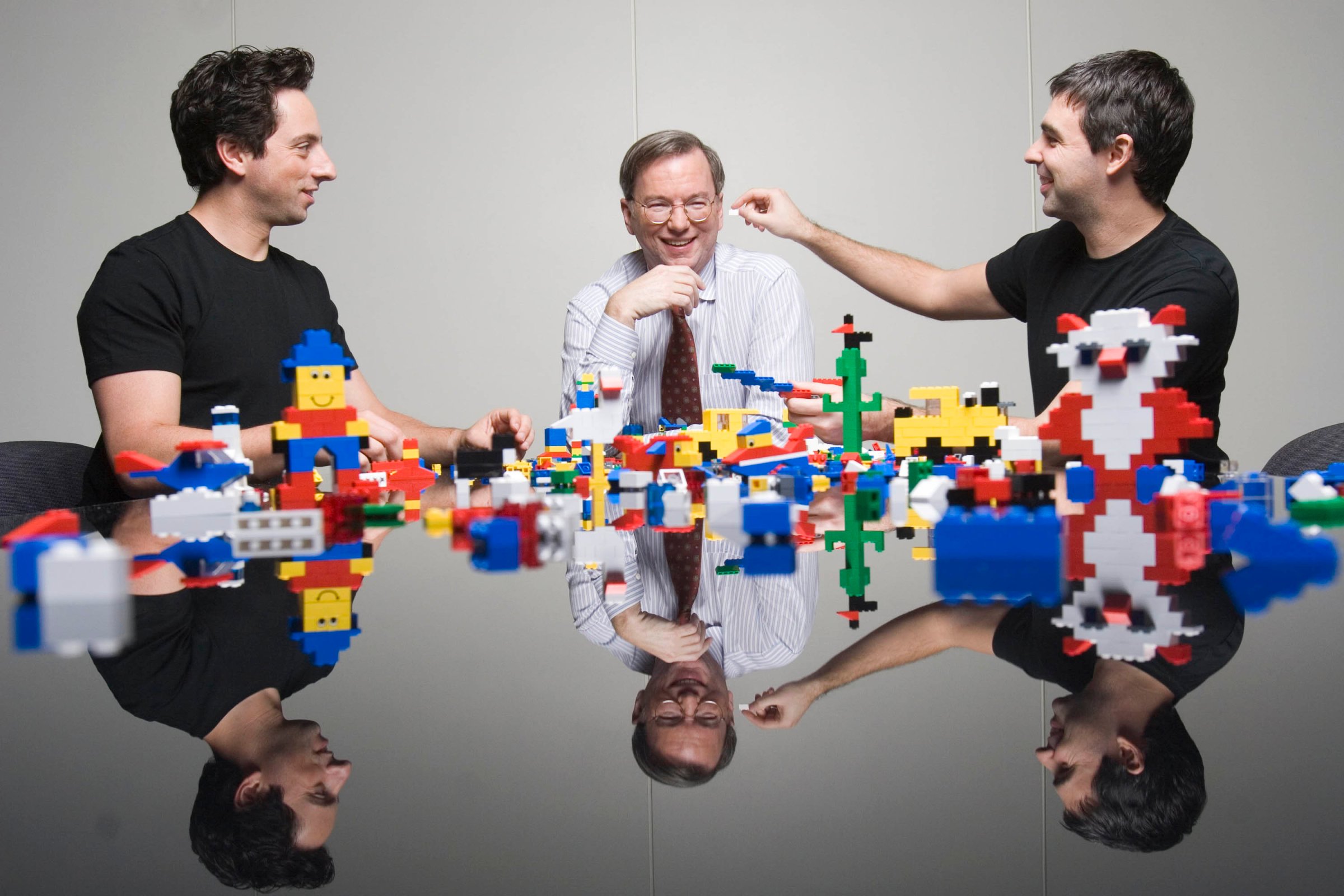

Alphabet–the name is a play on the diversity of companies it operates as well as a reference to alpha, a measurement of return adjusted for risk–will be overseen by Page, co-founder Sergey Brin and chief financial officer Ruth Porat. A slimmed-down Google, which generated almost all of the firm’s $66 billion in revenue last year, will be run by new CEO Sundar Pichai, a rising star who has overseen the company’s consumer products. Page likened the structure to the one employed by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, which owns well-known subsidiaries ranging from Geico to Dairy Queen.

More than a change of name or redrawn org chart is at stake. Google’s founders are grasping for an innovation model that can sustain the company in perpetuity–and perhaps show a way forward for other technology firms. History is rich with examples of companies that grew large and wealthy by mastering the tools of a particular era, only to ultimately become irrelevant. This problem, shorthanded as the “innovator’s dilemma” since Harvard professor Clayton Christensen coined the term in the late 1990s, has been simmering in Page’s and Brin’s minds since the company’s earliest days.

But how to endure in Silicon Valley is more or less a mystery. Apple’s model has been to continually disrupt itself, plowing profits from a current cash cow into ideas that will eventually eclipse it. IBM, before it, shed its signature business, computers, to evolve. Now Google’s founders surmise that they have found their own model. (Google declined to make executives available to talk about the strategy.)

Visiting the Googleplex, the company’s Mountain View, Calif., headquarters, has always been a nonpareil experience, not quite captured in parodies like the hapless Hooli campus on HBO’s Silicon Valley or the sinister offices of The Circle in Dave Eggers’ 2013 novel of the same name. It’s most akin to touring an Ivy League research institution on the first warm day of spring: Ph.D.s everywhere, some whizzing around on the company’s multicolored bicycles, some debating the limits of artificial intelligence on the lawn, many more indoors teaching algorithms to do new things. As a result, Google has at times seemed more like a collection of brilliant people whose pursuits are funded by a quirk in the evolution of the Internet–the wild profitability of search ads–than a firm with a vision.

This kind of kinetic culture is fine when a company is young. But with time, questions of how to maintain innovation and retain talented workers come to the fore. What’s more, over the past decade investors have gotten more adept at lobbying companies, no matter how profitable, that they deemed to lack focus. Apple and Microsoft, for instance, have been egged into instituting investor-enriching stock-buyback programs or giving up board seats. Google’s move–as well as Page’s promise to more transparently report the expenditures associated with its long shots–will presumably insulate Alphabet from such meddling.

More important, if it takes, the creation of Alphabet may come to be seen as a more sophisticated understanding of what drives innovation. Each subsidiary will have its own chief–often a brilliant figure. Nest, the smart-home-gadget maker, will have Tony Fadell, the so-called Godfather of the iPod. Google X, the research-and-development lab, will have Astro Teller, a computer scientist and novelist. Calico, charged with extending the human life span, will have Arthur Levinson, the former head of pioneering biotech firm Genentech. Not surprisingly, Page described Alphabet as “businesses prospering through strong leaders and independence.”

In this light, Alphabet begins to look more like a confederation of the world’s most ambitious companies than an unfocused, if very rich, tech company squandering its gains on a series of larks. Whether or not Page’s reshuffling amounts to more than semantics depends a great deal on what Alphabet does next. In time, the umbrella may expand. For example, the electric-car maker Tesla, which Google reportedly almost acquired in 2013, suddenly looks like a logical Alphabet company. Same for Twitter.

Then again, if the more focused, cash-generating Google subsidiary begins to flounder, Alphabet may come to be seen as the worst sort of misdirection. Google, after all, has a long history of management reorganizations that haven’t always hit the mark. (Analysts mostly cheered the Alphabet announcement, and Google’s market cap grew by $20 billion the following day.)

Finding a way to continue innovating is important for Google’s–or rather Alphabet’s–future. But there is an even more fundamental question in the background: What are corporations good for? At a base level, companies are “little platoons,” in the words of Edmund Burke, that represent the ties that bind and drive us forward. By reorganizing itself, Google is trying to find a logical way to support its own array of little platoons marching ahead.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com