This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Myth 1: Emperor Hirohito was a God

After the overthrow of the Japanese Shogunate in 1868, the four southern tribes, the Satsuma, Choshu, Saba and Tosa, sought to embed the legitimacy of their new regime by the re-promotion of an eighth century myth that the Japanese Emperor was a God. The myths were set out in two official chronicles, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters: AD 712) and the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan: AD 720).

The powers of the Emperor did not survive as power shifted to the Shogun system and until 1868 the Imperial Japanese family continued to exist largely in obscurity and often in relative poverty. As often happens with revolutionary regimes, a new national identity was required to justify and embed the country’s new military rulers. An infant Emperor Meiji was adopted as the new order’s figurehead and self-justification. Japan’s new regime re-emphasized the role of the Emperor as a living God, making it the heart of an ideological indoctrination taught in the new state school education system. The Japanese Army took this further by the simultaneous incorporation of Bushido (the military scholar code) into its military programs. Thus the overthrow of the Shogun was portrayed less as a revolution and was characterized instead as the Meiji Restoration, a title that gave moral justification to a successful armed insurrection.

Myth 2: Hirohito was simply a constitutional monarch forced into war by his generals

In March 1946, some nine months after the Pacific War had been brought to an end, Emperor Hirohito made a testament about his role in the war. In a bizarre scene, Hirohito had a single bed set up on which he lay in pure white pajamas on the finest soft cotton pillows. In eight hours of statements, the Showa Tenno no Dokuhaku Roku (Emperor’s Soliloquy: his post-war testament) Hirohito absolved himself for all responsibility for the war by claiming that he was a constitutional monarch entirely in the hands of the military: ‘I was a virtual prisoner and was powerless.’

This was a lie. Although by convention Hirohito behaved as a constitutional monarch, the Meiji Constitution granted him absolute power – he was after all enshrined as a God. On three separate occasions during his rule he had demonstrated his absolute powers; in 1929 he forced the resignation of his prime minister; in 1936 he overruled his military advisors to insist on the harshest treatment of the young officers involved in the coup d’etat known as the 26 February Incident in 1945; and finally in August 1945 he overruled his advisors by insisting on a Japanese surrender. Hirohito had the power to stop Japan’s military adventurism in the 1930s but chose not to. As his former aide-de-camp Vice-Admiral Noboru Hirata conjectured, “What [his majesty] did at the end of the war, we might have had him do at the start.”

Myth 3: Hirohito was a peace-loving scientist only interested in ocean mollusks

After the Pacific War, General MacArthur’s propaganda machine as well as the Imperial court went into overdrive to convince the world that the Emperor was a peace loving man, a scientist, whose main interest was the study of hydrozoa, microscopic jellyfish. Hirohito was indeed an avid gentleman scientist. However he was also a young man with an interest in the minutiae of military activity. He had a war room built underneath the Imperial Palace in Tokyo from where he could follow Japan’s military adventures in detail. Even the military hierarchy complained at the level of resources needed to update the Emperor. Throughout the war, he mainly wore a military uniform and to celebrate great victories he rode a pure white charger in parades in front of the Imperial Palace. Furthermore, although the Emperor’s court papers were destroyed before the Allies could seize them, it seems clear from contemporary accounts that as Japan’s war situation deteriorated, that he became increasingly shrill in his criticisms of the military, and more insistent on his own strategic suggestions.

Myth 4: Hirohito did not know about the Rape of Nanking and the genocide in China

The Rape of Nanking was widely reported in the Japanese Press, even relaying in gory detail a competition between officers as to who could cut off most Chinese heads. Hirohito could not have been unaware of these reports particularly as his own family was closely involved in the atrocities in China. His own uncle, Prince Asaka had commanded the Japanese troops at Nanking. As a reward Hirohito gifted Asaka a pair of silver vases and they also resumed their regular games of golf.

In a genocide that killed 20 to 30 million Chinese, the Emperor’s relation, Field Marshal Prince Kanin, gave the authorization for the use of gas. Prince Mikasa, Hirohito’s youngest brother, even visited Unit 731 in Manchurian where live vivisection and other experiments were carried out on Chinese and western prisoners. Although unproven, it seems highly unlikely that the inquisitive Hirohito would have been uninformed by his relatives of these activities conducted by the Japanese Army. Like Hirohito, all the imperial family was excused prosecution at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Myth 5: Hirohito apologized for Japan’s war crimes in the Pacific War

It is variously reported that Emperor Hirohito offered to give a formal apology for Japanese war crimes including the attack on Pearl Harbor. Supposedly MacArthur, in order not to undermine the Tokyo War crimes trials refused to allow this. However if Hirohito had really wanted to issue an apology to the nations of Asia and to the United States he could surely have done so by handing a press release to the international press. In 1975, when asked about the “responsibility for the war,” Hirohito replied, “I can’t comment on that figure of speech because I’ve never done research in literature.” It is an obfuscation that is fully reflected in the Japanese post-war historiography taught in schools and universities.

Francis Pike is a historian, journalist and specialist in Asian economics, politics and history. He is the author of Empires at War: A Short History of Modern Asia Since World War II (2009). His latest book is Hirohito’s War: The Pacific War, 1941-1945 (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015).

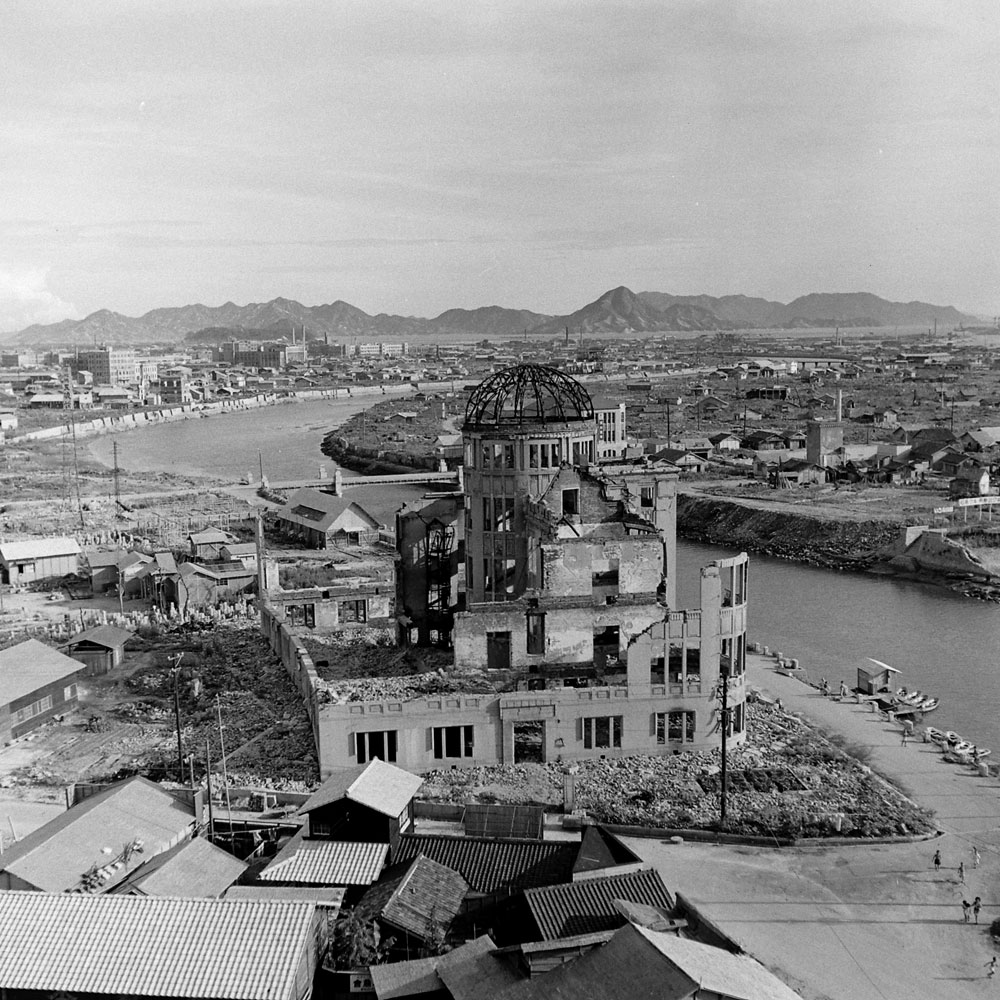

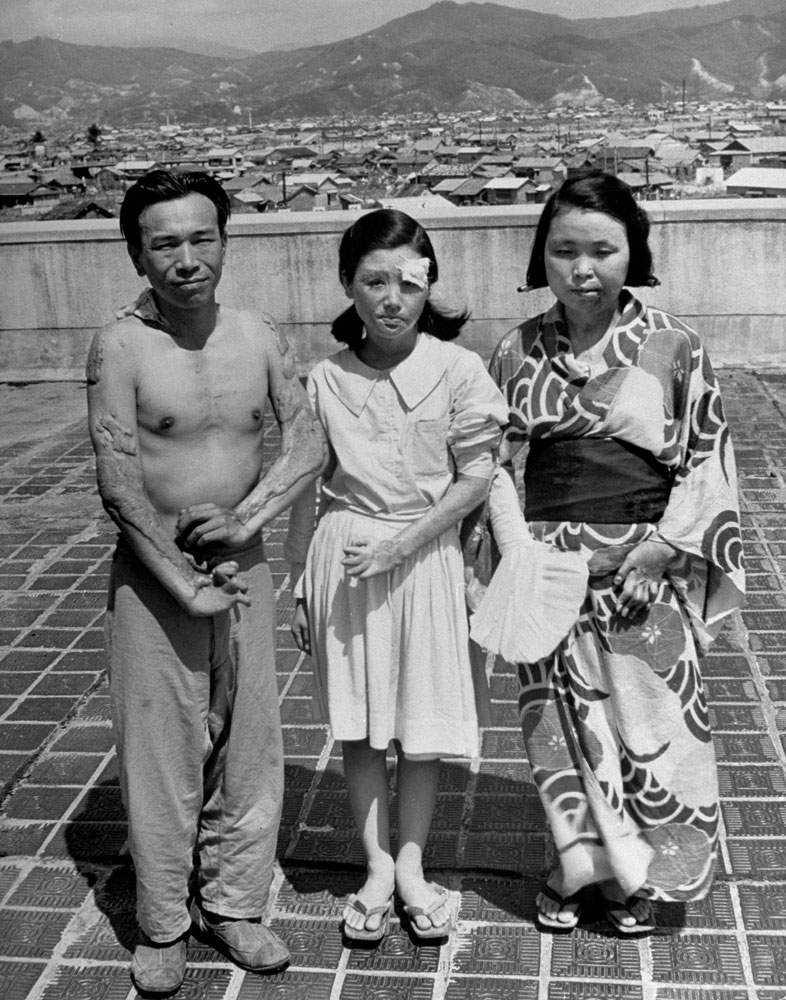

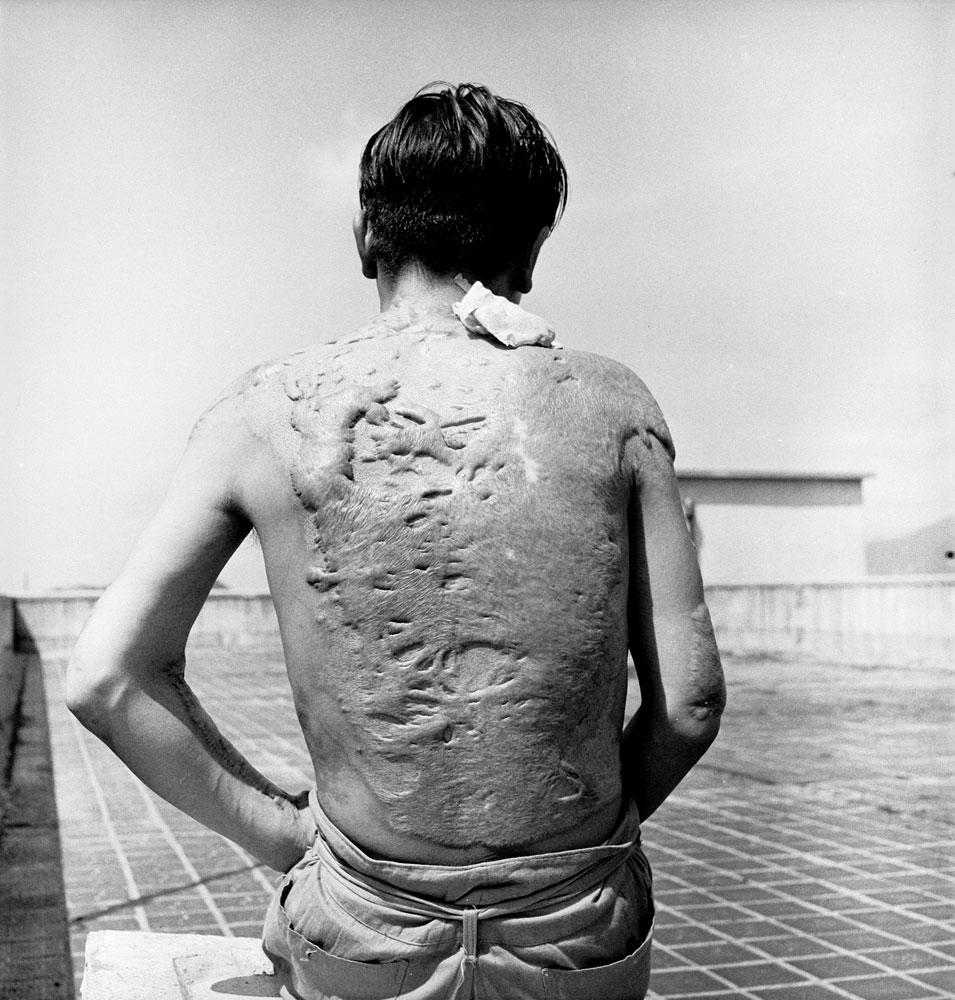

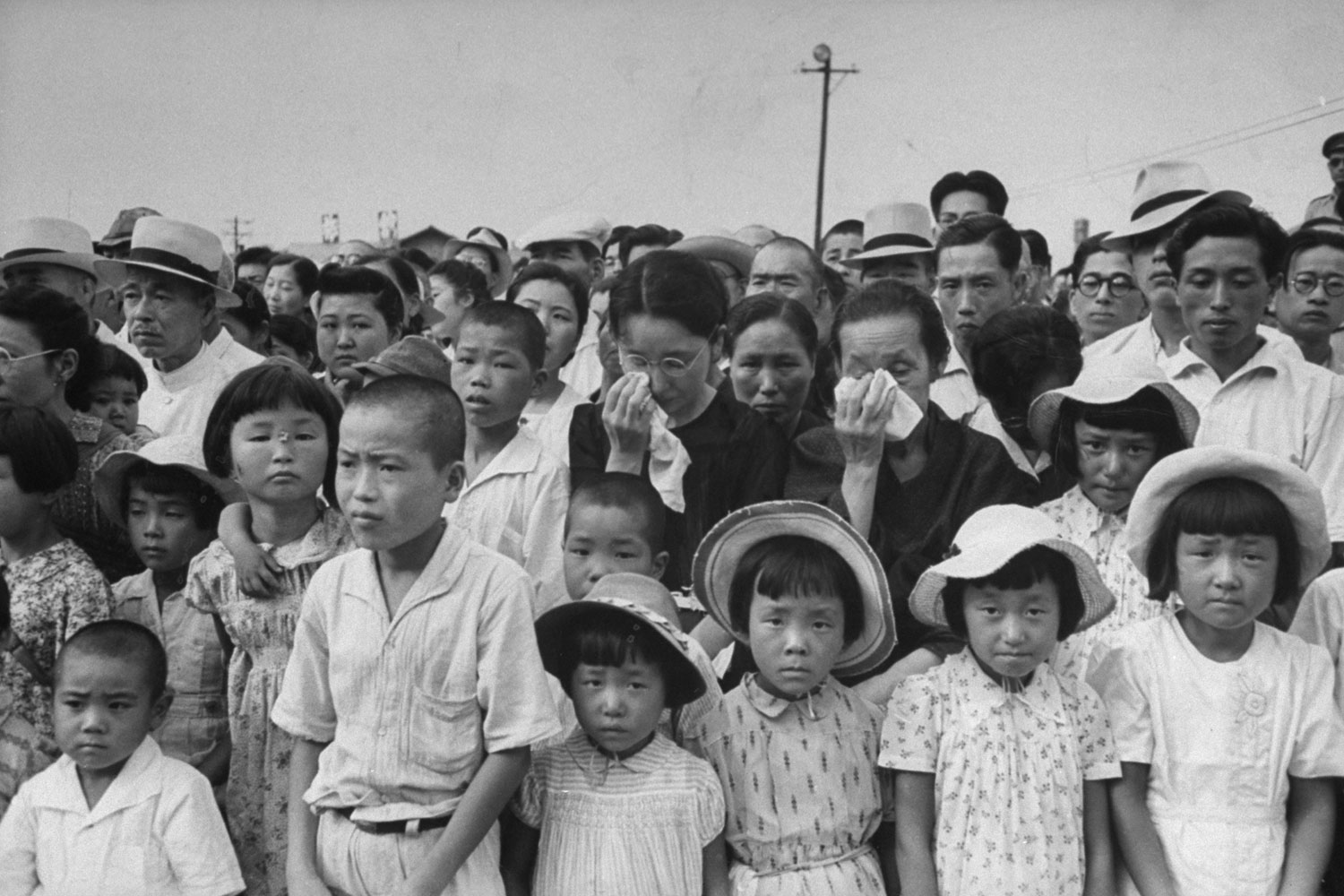

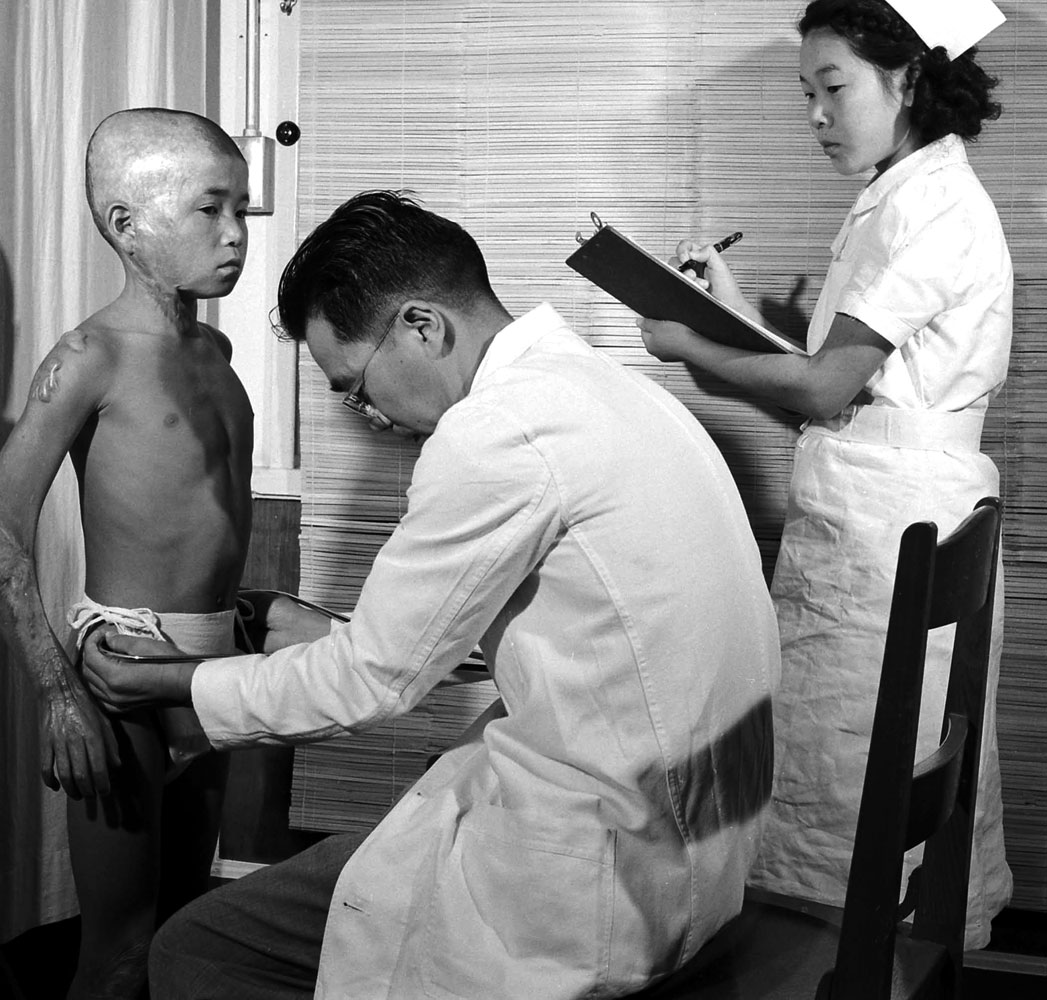

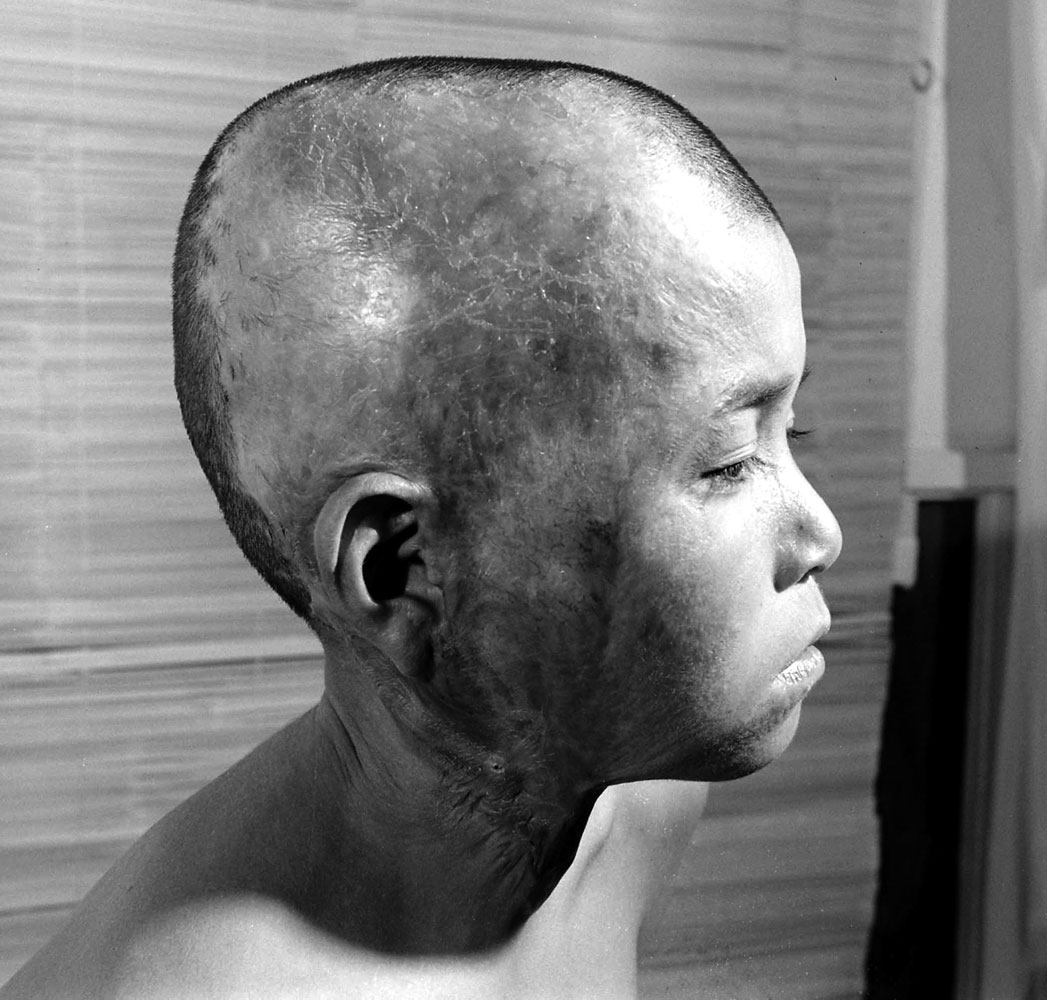

After Hiroshima: Portraits of Survivors

![Hiroshima's children patiently wait their turn for a complete and detailed physical examination in ABCC's [Atom Bomb Casualty Commission] temporary laboratory clinic.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/14_00717439.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com