This post is in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin. A version of the article below was originally published on the Ransom Center’s Cultural Compass blog.

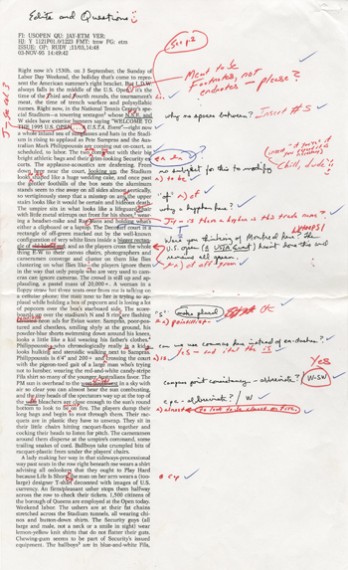

In 1995, Jay Jennings, a former editor of Tennis magazine, commissioned David Foster Wallace to write an article about the U.S. Open, which was published as “Democracy and Commerce at the U.S. Open” one year later. In 2010, Jennings contributed a file of corrected proofs and correspondence to the Ransom Center relating to the essay and revealing Wallace’s close involvement in the editorial process. Wallace had warned Jennings that he would be a difficult editee, but the papers demonstrate the contrary. Though Wallace’s comments on the proof pages are often assertive, they are equally good-natured, dotted throughout with smiley faces, and oftentimes showing his humor. Jennings recounts his working with Wallace:

In 1995, I contacted a young writer named David Foster Wallace to ask if he would come to the U.S. Open over Labor Day weekend and riff on the scene, not so much the one on the court but that going on all over the grounds of the National Tennis Center in New York. Though he was not widely known, editors were clamoring to have him to riff on some scene or another on the basis of a hilarious, hyperobservant essay he’d published in Harper’s magazine in 1994 about the Illinois State Fair. A few years earlier he’d written about playing junior tennis on the windy plains of the Midwest for Harper’s, so I knew he was a deft player and knowledgeable fan. The lure of the all-access media pass was the clincher and he agreed to do the story for much less than he could have commanded elsewhere.

We put him up at the official hotel, the Hyatt above Grand Central Station in Manhattan, and I met him in the lobby on Sunday morning to ride the shuttle bus out to Queens. Unshaven and in his trademark bandana, he looked the part of a raucous rock star but was unfailingly polite, appreciative, and both excited and a little nervous. At the site, we settled into the main stadium for the marquee match that day, between eventual champion Pete Sampras and a rising Australian star, Mark Philippoussis. I remember being concerned by how few notes he was taking in his tiny notebook and wondering if he was getting enough material. We chatted about tennis and books and other things, I pointed out my boss (a woman in a sunhat nearby), and after the match he decided to wander off on his own. Over the next two days, we’d meet up occasionally on the grounds, and as we were leaving together one day, he asked me if I wanted to join him and his friend Jon (Franzen, then a struggling novelist in New York) for a showing of Larry Clark’s film KIDS that night. My then-wife had other plans for us, so I had to demur, to my eternal regret, relegating myself to an even smaller DFW footnote in literary history. The story he produced from that weekend and his tiny notebook proved to be one of the longest (and best) Tennis magazine has ever run, and I had difficult battles with the lady in the sunhat, as Dave and I came to call her, to see that it was published as Dave intended it, footnotes, eccentric abbreviations and all. In the essay, after having spent only a few days there, he had crystalized all the annoyances, grievances, glories and grandeur that those of us who had been attending the event for years had observed but with more humor, sharpness and empathy: the “felonious” price of the Häagen-Dazs bars, the “big ginger beard” that made one of the ball boys look like a “ball grad student,” and the “mad crane” style of a 6’6″ player.

We held the story for a year to run in our 1996 U.S. Open issue, and in the interim, Infinite Jest was published and Dave became the reluctant darling of the literary world. After the issue appeared, he generously wrote to thank me for the short profile I’d written of him for the magazine’s “Editor’s Page” and, again later that year, to explain why the Tennis story would not appear in his collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, even though he thought it better than another tennis piece, “The String Theory,” originally from Esquire: the latter had received more attention and to include both would be too much tennis for the book. He didn’t owe me that explanation but, like his intellect, his empathy was wide-ranging and deep, and he knew that having the Tennis story in the collection would probably help my editing career. Instead, I got a consolation prize I enjoyed even more: he put me in the acknowledgements as “Jay (I’m Suffering Right Along With You) Jennings,” commemorating our joint battles with my superior.

We continued to correspond sporadically over the years, the last time just months before he took his own life, when I wrote to him about an exhibition match I’d seen between the retired Pete Sampras and John McEnroe. He replied by postcard that he thought McEnroe was ‘so lovely to watch play’ but ‘a ghastly TV commentator,’ a contrarian view I shared. When I heard he’d committed suicide, I remembered an earlier postcard he’d sent me, not so much for what he wrote, which was typically funny and kind, but for the picture. It showed a detail from the exterior of Salisbury Cathedral in England, a close-up of a stone bust in a silent, eternal, open-mouthed scream; on the verso, the work, a portrait of pain, was identified simply as “Head of Man.”

Jay Jennings is the author of Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City, and the editor of Tennis and the Meaning of Life: A Literary Anthology of the Game and Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany.

See more about the Ransom Center’s collection here at the Harry Ransom Center blog

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com