The U.S. flew “no-fly zones” over northern and southern Iraq for more than a decade before the 2003 U.S. invasion that toppled Saddam Hussein. U.S. warplanes kept Iraqi aircraft out of the sky, and targeted Iraqi air-defense systems that threatened to shoot. Now, along with neighboring Turkey, the U.S. is planning to launch something similar over a stretch of northern Syria.

Eliminating Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria along a strip of the Syrian-Turkish border is the key goal, opening up a safe haven for tens of thousands of Syrians displaced by the country’s four-year-old civil war that has killed more than 200,000. Whether the move hastens the ouster of Syrian dictator Bashar Assad—or leads to the shootdown and possible capture or death of an American pilot—remains unknowable.

U.S. officials stressed Monday that Washington and Ankara are planning to step up bombing of ISIS targets on the ground, and not create a formal no-fly zone, which would bar Syrian warplanes from bombing runs. “It’s not a no-fly zone—it’s a bombing campaign,” says retired Marine general Anthony Zinni, who oversaw the Iraqi no-fly zones as chief of U.S. Central Command from 1997 to 2000. He doesn’t think such a bombing campaign will have much effect. “We see how well a year of bombing has worked in Iraq,” where ISIS remains in control of much of the western part of the nation.

The chance of clashes between Syria and U.S. and Turkish aircraft will be more likely once details of the new zone are hammered out and stepped-up U.S.-Turkish attacks on ISIS targets begin. “I think they’ll tell the Syrians to just stay out of the air space,” Zinni says of U.S. and Turkish commanders. “They’ll issue a demarche: ‘If you shoot any air defense weapons at us, we’ll nail you.’ That’s what we did to the Iraqis.”

State Department spokesman John Kirby said Monday that the Syrians aren’t challenging U.S. warplanes. “There is no opposition in the air when coalition aircraft are flying in that part of Syria,” he said. “The Assad regime is not challenging us; [ISIS] doesn’t have airplanes … they’re not being shot at.”

But that’s hardly a guarantee. U.S. commanders will ensure their flight crew fly high and well clear of any known Syrian air-defense threats to minimize the chance of a U.S. pilot being shot down and—in the worst case—falling into ISIS’s hands and murdered. But accidents and snafus can occasionally happen. “We never even had a plane scratched,” Zinni says of the more than 200,000 U.S. flights in the Iraqi no-fly zones from 1992 to 2003. “It was absolutely remarkable.” (Unfortunately, this record was marred by the 1994 shootdown of two U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopters, killing all 26 aboard, by a pair of U.S. Air Force F-15s.)

Conflicting loyalties and priorities complicate the more aggressive campaign. Last week, after a suicide bombing blamed on ISIS killed 30 in a Turkish border town, Turkey began flying air strikes against ISIS targets in Syria, and gave the U.S. long-sought permission to launch air strikes from Turkish bases. Turkey, a NATO ally, is growing increasingly concerned with ISIS on its doorstep, the growing refugee problem, and military successes by its Kurdish minority, some elements of which are seeking their own state.

Kurdish forces control most of the Syrian-Turkish frontier, and the Turkish government views them as a threat much like ISIS. Ankara is also more interested in toppling Assad than battling ISIS. “If there is one person who is responsible for all these terrorist crimes and humanitarian tragedies in Syria, it is Assad’s approach, using chemical weapons, barrel bombs against civilians,” Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu told CNN. His government has called for a NATO meeting Tuesday to discuss the ISIS fight.

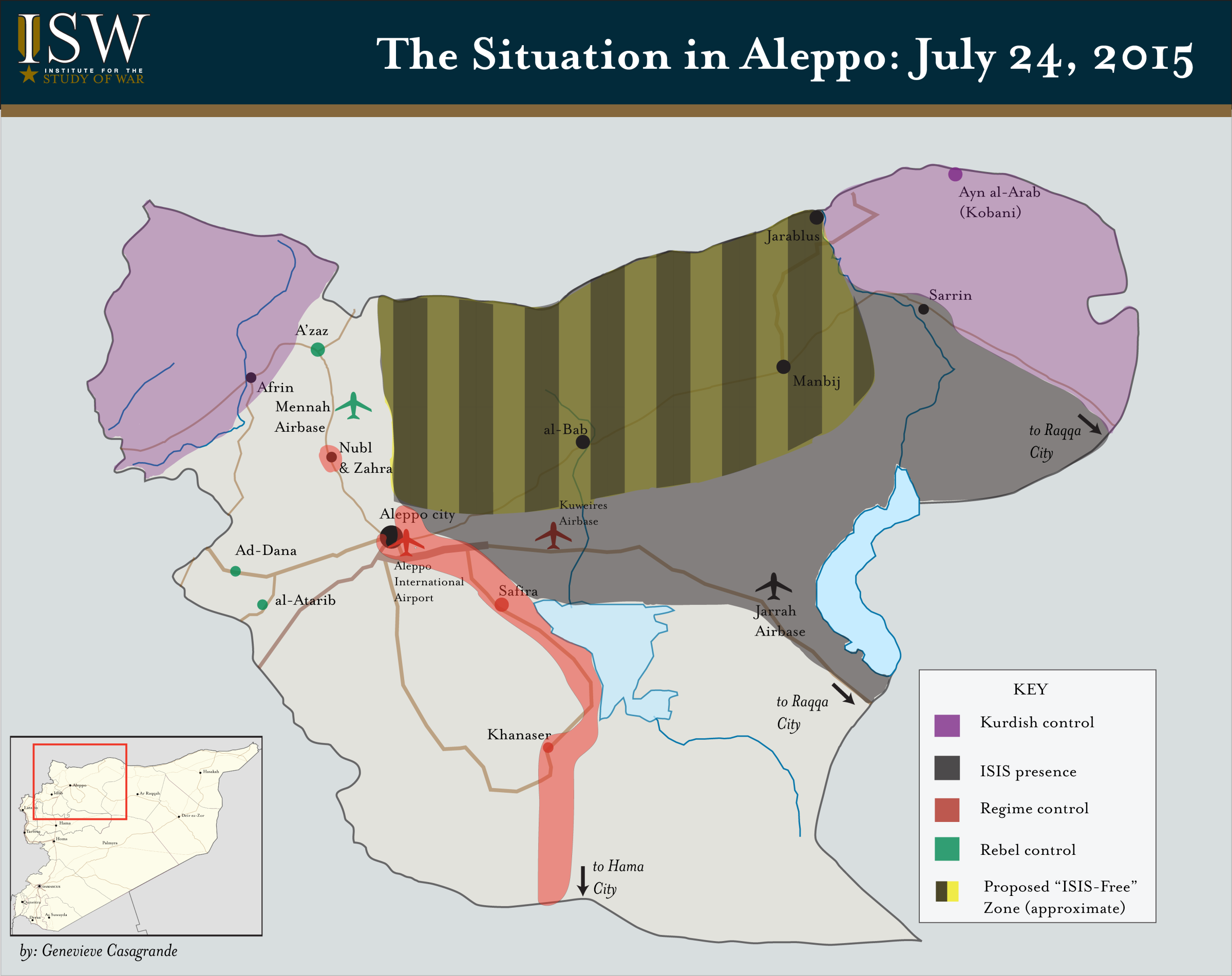

U.S. and Turkish air power are expected to be used to reinforce Syrian rebels on the ground who are battling ISIS, creating a 68-mile “no-ISIS zone” along the Syrian-Turkish border. “Moderate forces like the Free Syrian Army will be strengthened…so they can take control of areas freed from [ISIS], air cover will be provided,” Davutoglu told Turkey’s A Haber television news channel.. “It would be impossible for them to take control of the area without it.”

U.S. officials have been complaining since the Pentagon began bombing ISIS targets a year ago of a dearth of reliable partners on the ground, in both Iraq and Syria. ISIS drove the U.S.-trained Iraqi army out of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, a year ago, and the U.S. has trained only about 60 Syrian rebels to fight ISIS’s 30,000-strong force.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com