Jeb Bush’s official campaign headquarters sits tucked away in a nondescript Miami corporate park, across from a Wal-Mart SuperCenter and around the corner from a Chick-fil-A and a Denny’s diner. Bush’s plane tickets and hotel rooms are reserved by schedulers in the grey fortress. His speeches are drafted in dank cubicles. When his top lieutenants on his payroll meet, they huddle in the conference room in a bunker-like former utility building about 10 miles from Miami’s glorious beaches.

But the real base of power for the former Florida Governor’s bid for the White House is almost 3,000 miles away in Los Angeles. When it is time for millions of dollars of television ads to start, that happens in the Carthay neighborhood. There, longtime Bush adviser Mike Murphy and his team of fewer than a dozen ad makers, researchers and digital ninjas collaborate in a spacious, light-filled office suite that is more fitting for a Hollywood blockbuster than a political campaign. Already, the super PAC has raised $103 million—some of it with Bush’s direct help.

Welcome to the new type of White House campaign, one where the biggest spender is not the candidate and outside advisers will have more interactions with voters than anyone on the ballots. A handful of deep-pocketed donors can pick up the tab for a massive advertising blitz and only a Kleenex-thin barrier keeps the outside groups from the campaigns. When Sen. Ted Cruz was ready to release a summary of his fundraising to date, his campaign included the super PAC’s haul, too, lumping the whole sum together.

Maybe they should. The team running what is now the Bush campaign and the Bush super PAC huddled frequently at the Dallas Hyatt to plot strategy before the race officially got started. Sen. Rand Paul has his nephew-in-law running his nominally independent super PAC. Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal’s super PAC is run by his one-time boss, former Rep. Bob Livingston.

But Bush’s approach to the super PAC is the one that is—depending on who is telling the story—either the most imaginative or the most audacious.

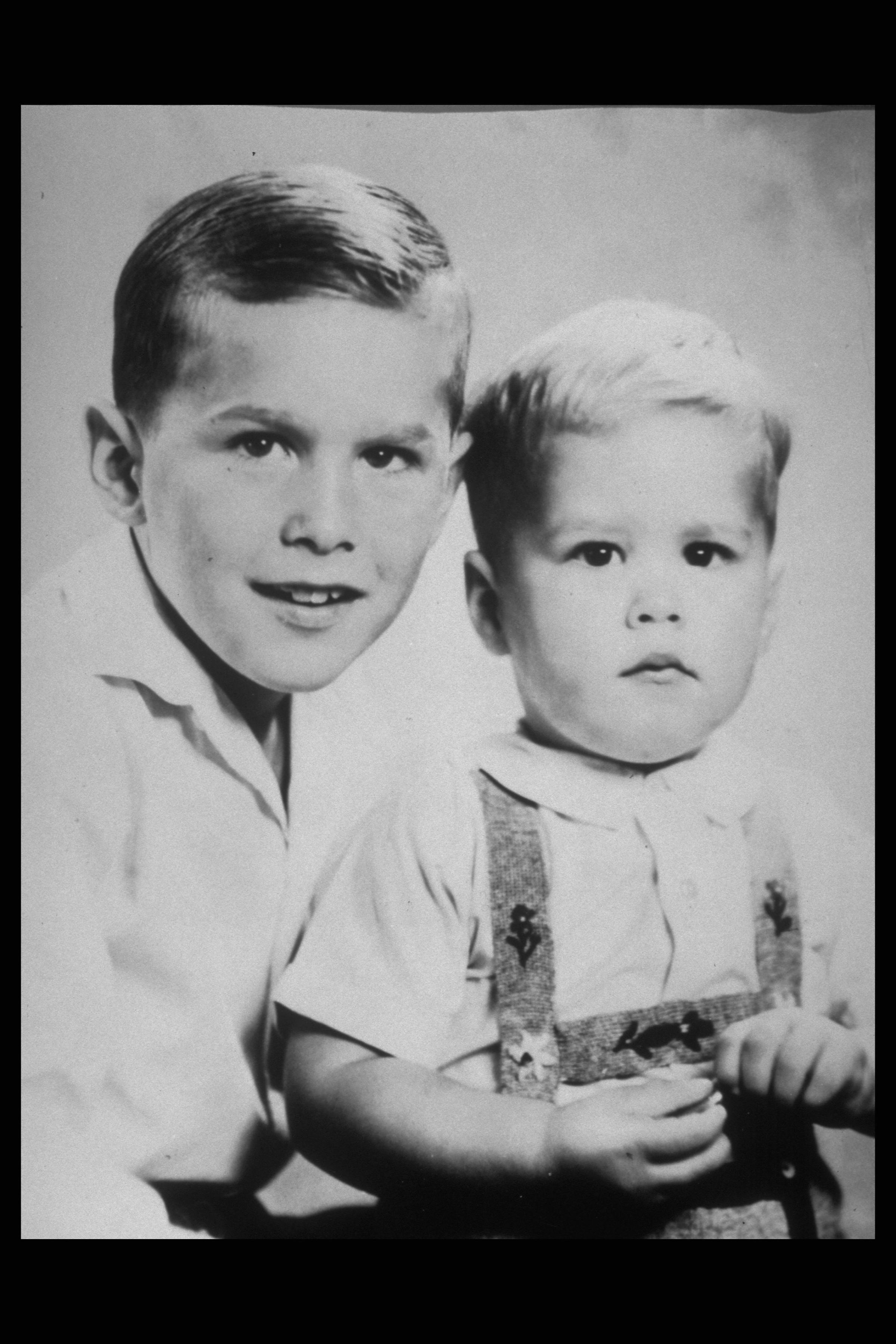

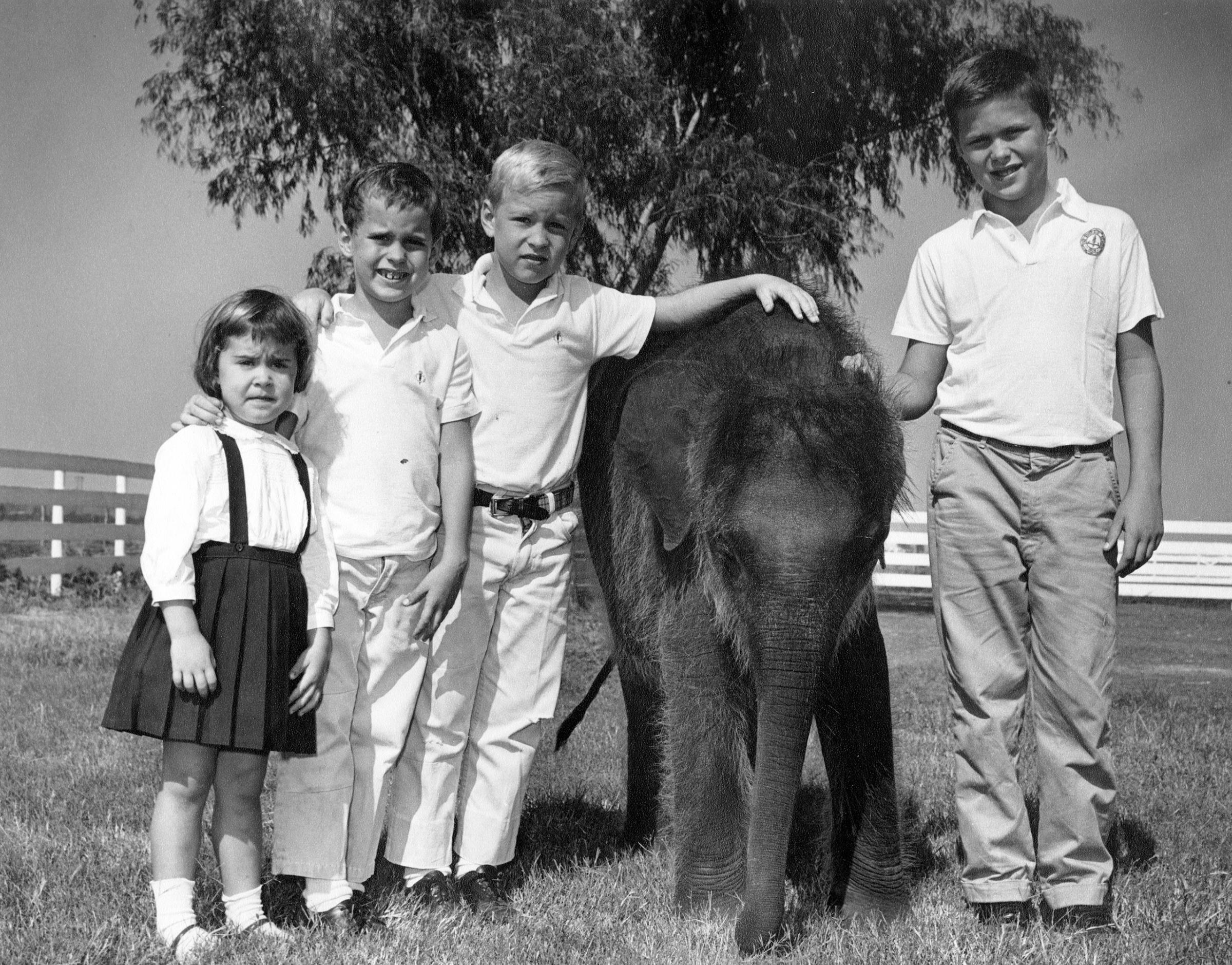

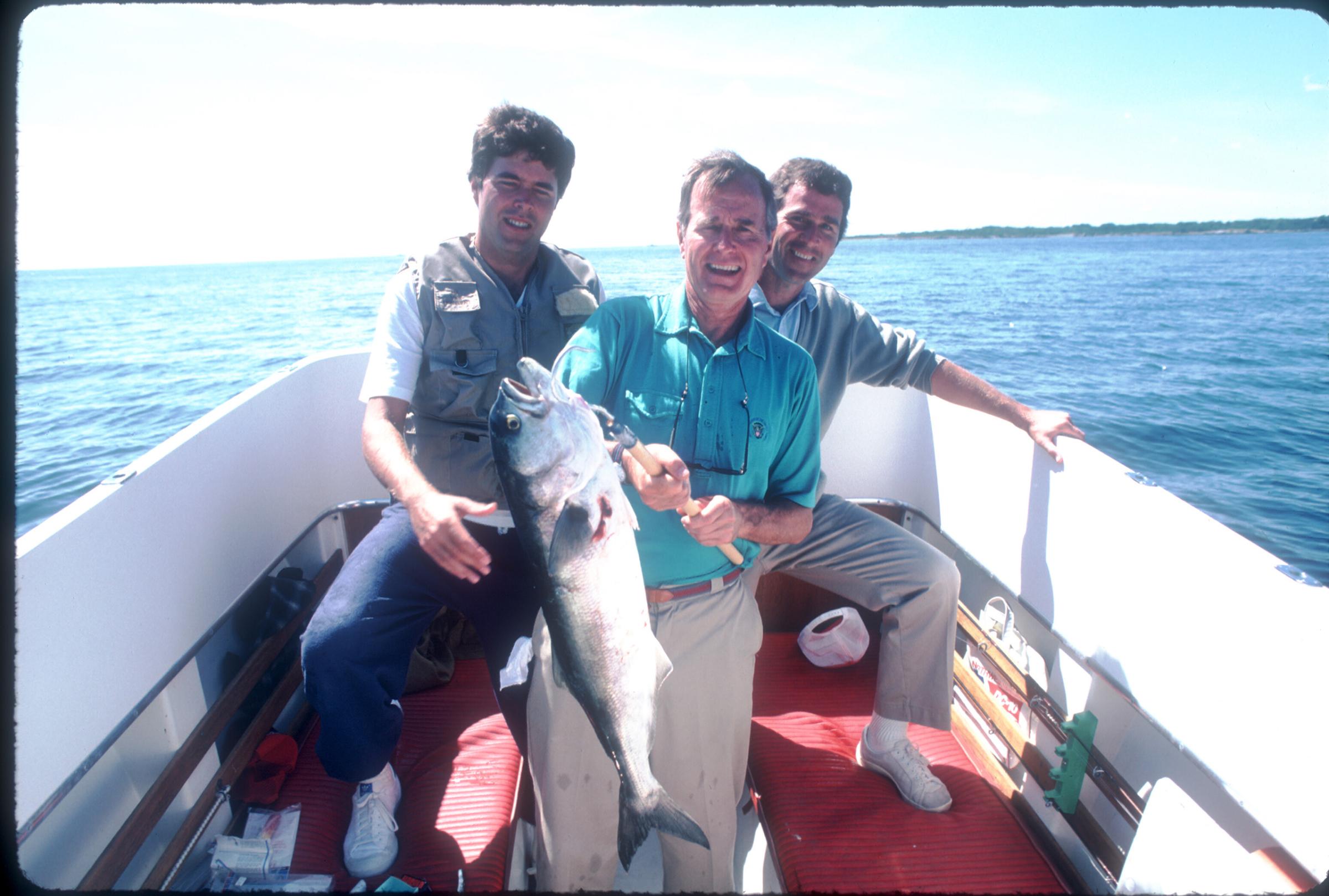

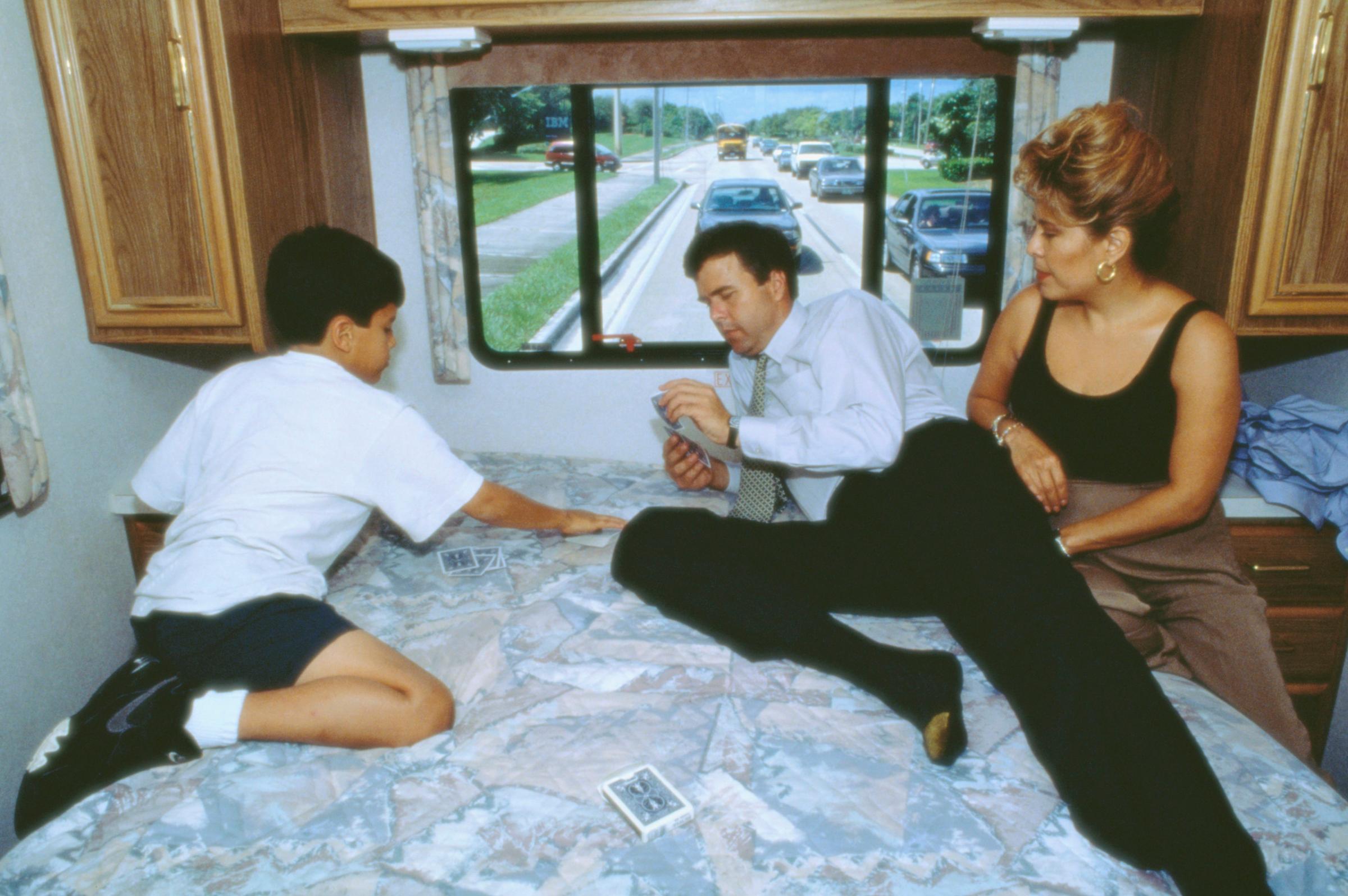

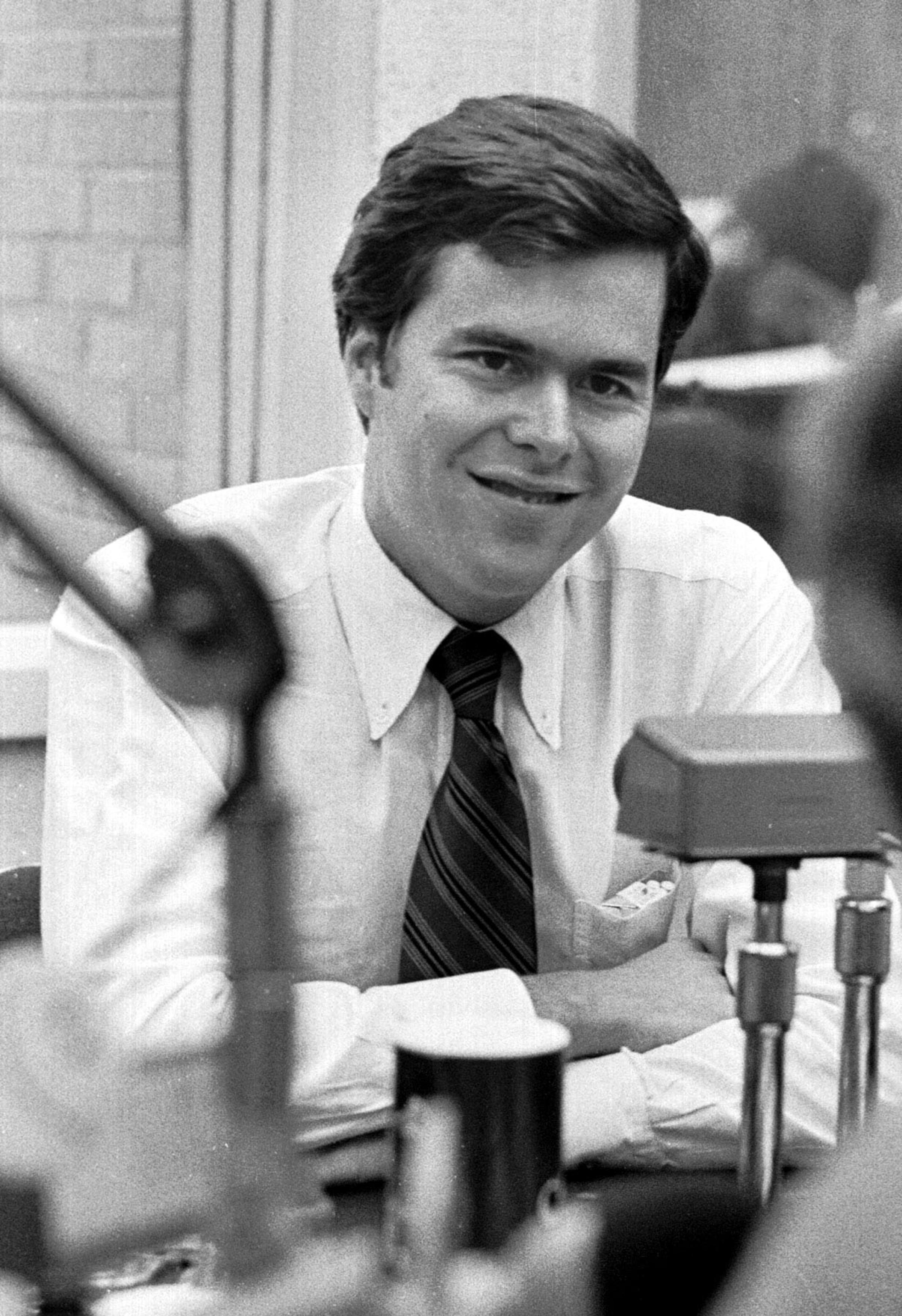

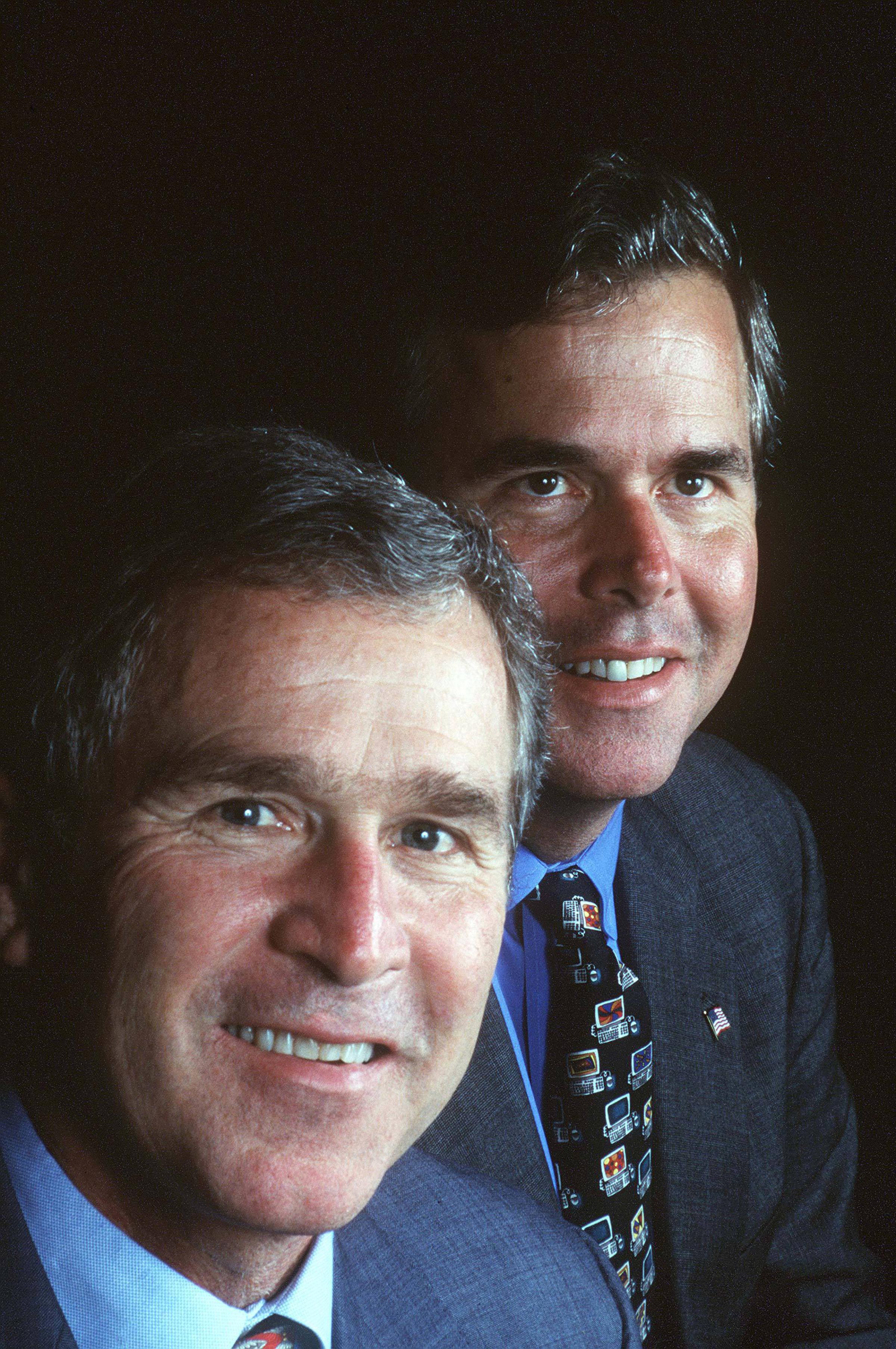

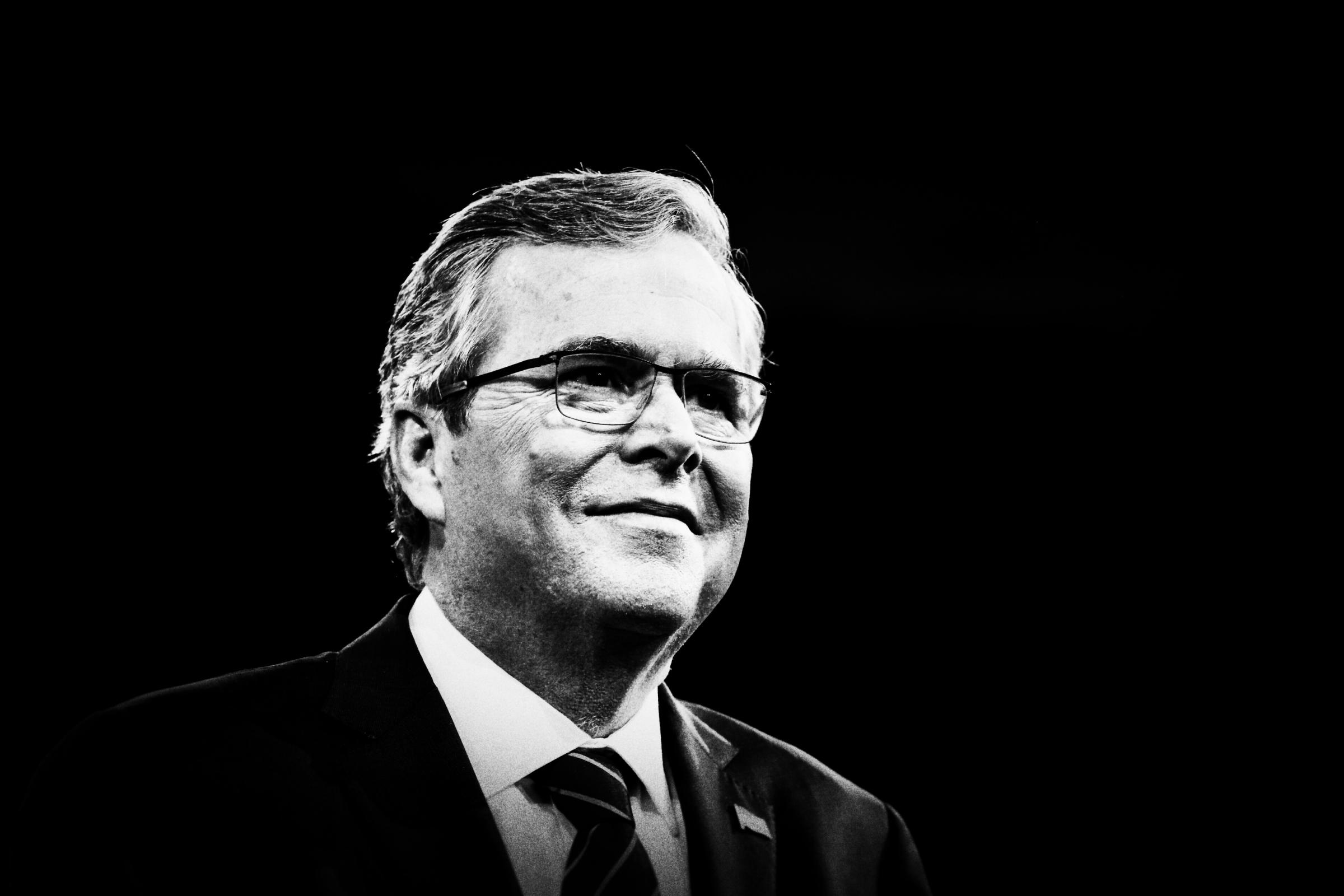

See Jeb Bush's Life in Photos

Campaign and super PAC aides could, and did, discuss broad strategies for how to approach the primary and general elections, including the strengths and weaknesses of Bush and his Democratic and Republican rivals. But where some advisers have maintained that campaigns and super PACs could coordinate during the entire pre-campaign period, Bush’s team opted for a more conservative position, banning all coordinated talk of specific expenditures.

For example, they could discuss Ben Carson’s vulnerabilities as a first-time candidate, but couldn’t plan for a specific ad hitting him on that in the week leading up to the Iowa Caucuses.

“The timing of having a super PAC publicly acknowledging it supports a candidate and raising money early, allows you huge flexibility in using that money,” said one person briefed on the Bush campaign and super PAC’s plans.

On Thursday, Bush’s campaign announced it raised $11.4 million over just 16 days. An hour later, Right to Rise USA released its fundraising haul: a record $103 million haul, with $98 million cash on hand.

By raising so much, so soon, Bush’s team is hoping to get a jump on ad reservations—a tactic already employed by Sen. Marco Rubio’s far smaller independent effort—seeking to avoid a repeat of one of Mitt Romney’s critical errors. In 2012, one third of Restore Our Future’s funding came in in the final eight weeks of the campaign, at which point the airwaves were already saturated and the group had to pay high prices for fewer ads than the pro-Obama efforts.

Now the group can reserve TV ad time, invest in a digital operation, explore mail—with its six-week lead time—and potentially run a phone banking operation. It’s a flexibility that has never-before-existed in a presidential campaign.

Early indications were that the super PAC could have branched into field work on behalf of Bush’s campaign, much like how fellow Republican candidates Carly Fiorina and Bobby Jindal have used their outside groups. But the effort was abandoned, at least for now, because most of the benefit of field work comes from coordinating with the campaign.

The Bush super PAC has already started spending its money, beginning this week with a $47,000 digital effort opening salvo in Iowa and New Hampshire to boost Bush and attack former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Senior Right to Rise aides say that they’re following a playbook written and run before. The change now, however, is that they’re getting started sooner and more openly. The pro-Bush effort is unusual in that it was formed and raised money heavily before Bush was a declared candidate, and was clear about its association with him. Aides say Bush never directly made a fundraising ask, even before he declared his candidacy.

Coordination rules prohibit scripting an ad featuring the candidate, but the super PAC has found clever workarounds. At Bush’s announcement event, a space on the press riser alongside the likes of NBC and ABC was reserved for Right to Rise USA. The group released a super-cut of the speech set to soaring music a week after the announcement. The catch: they had to white-out any official campaign signage.

That’s not all. The super PAC’s film crews did hours of interviews with Bush about his legislative and personal records, including education reform and cutting the size of Florida’s government, which can be cut down later into an ad by the super PAC team. In essence, the super PAC banked the bulk of its footage for commercials before it had an official candidate.

But there are challenges to such an approach. In a traditional campaign structure, if an ad maven needed details of the candidate’s record, he or she could phone up the candidate or walk down the hall to ask for specifics in person. Murphy cannot do that. To remedy that, Murphy has done the next best thing: he hired a longtime aide to Bush during his time as Governor. That individual is now the link between Bush’s record as Governor and his current campaign’s super PAC.

Also, if a candidate hated an ad, he or she could shelve it. With a super PAC, there’s no mechanism for the candidate to kill it. The scofflaw message can air thousands of times and there’s nothing a candidate can do. But if everyone in Bush’s orbit sticks to the pre-campaign plan, that should not be a problem. After all, they spent months practicing for this moment.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com