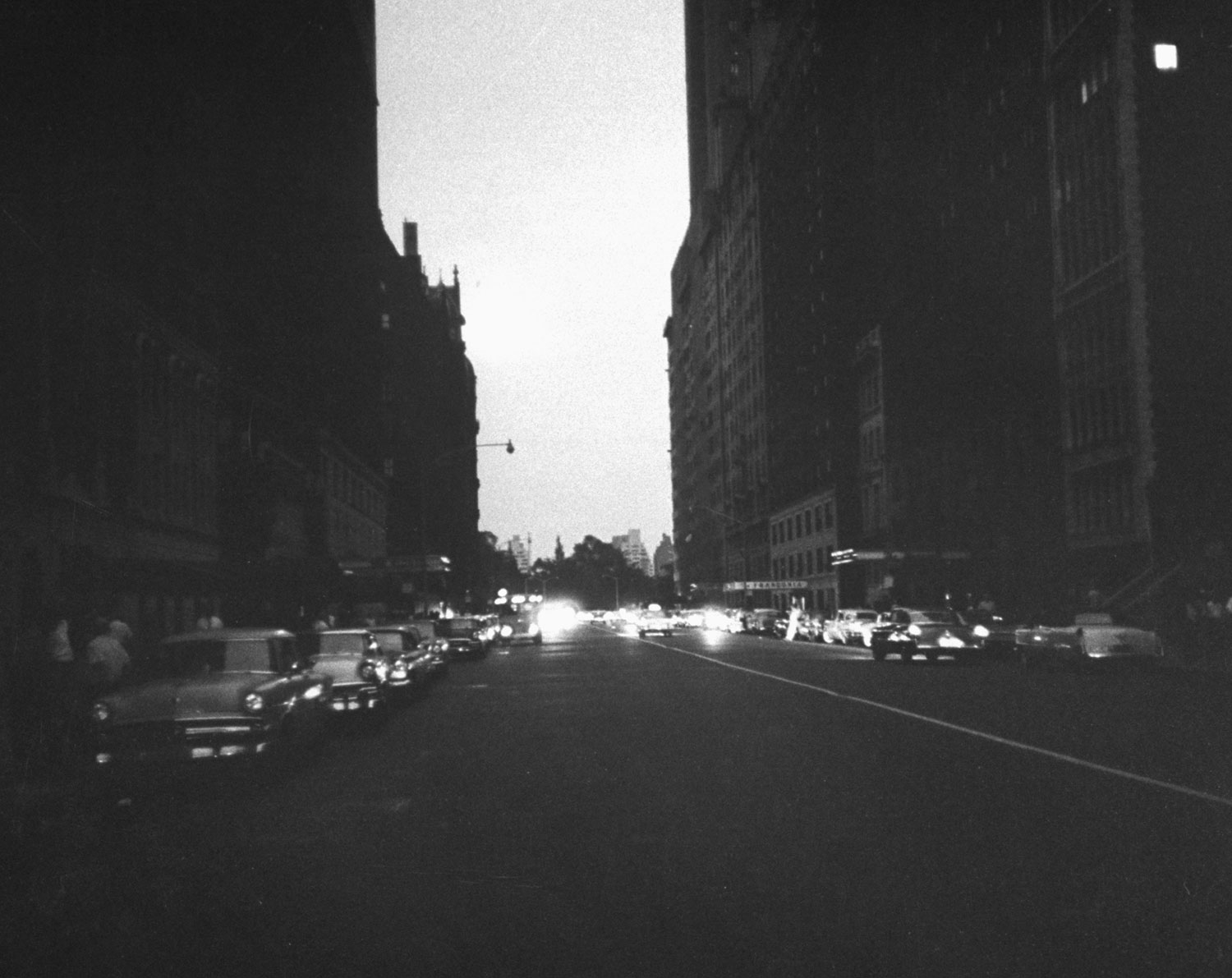

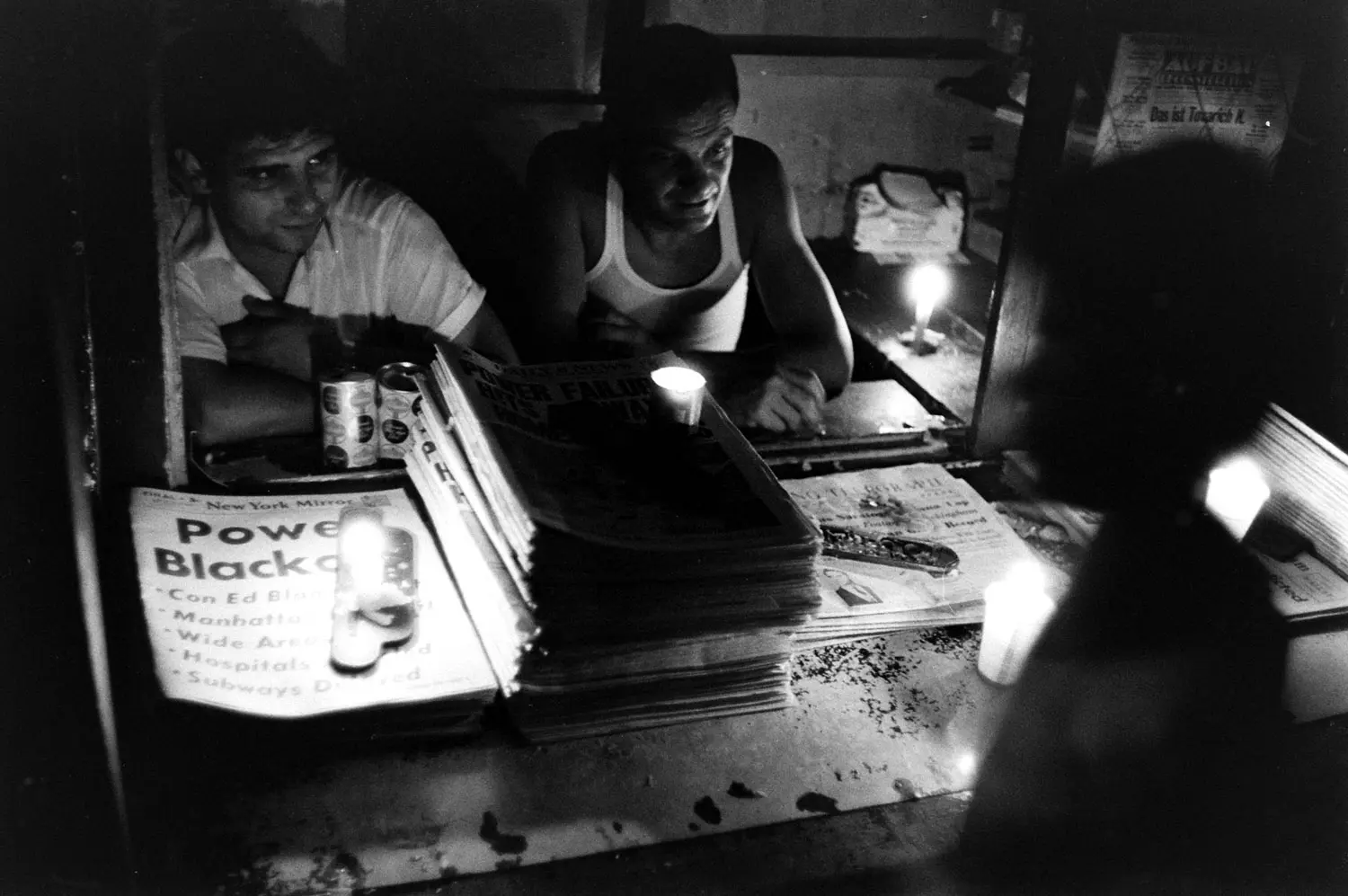

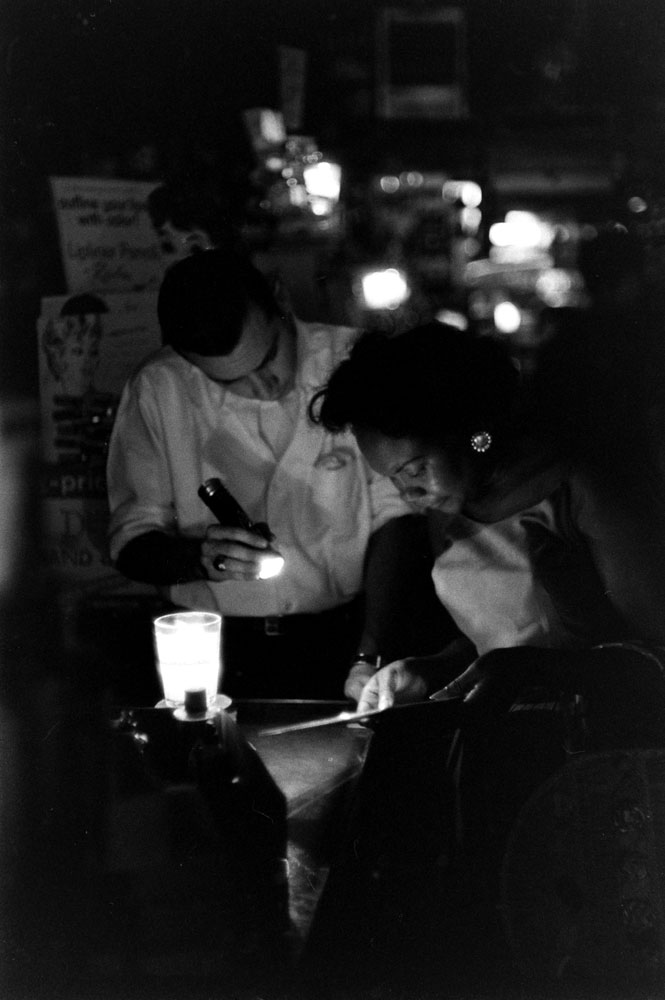

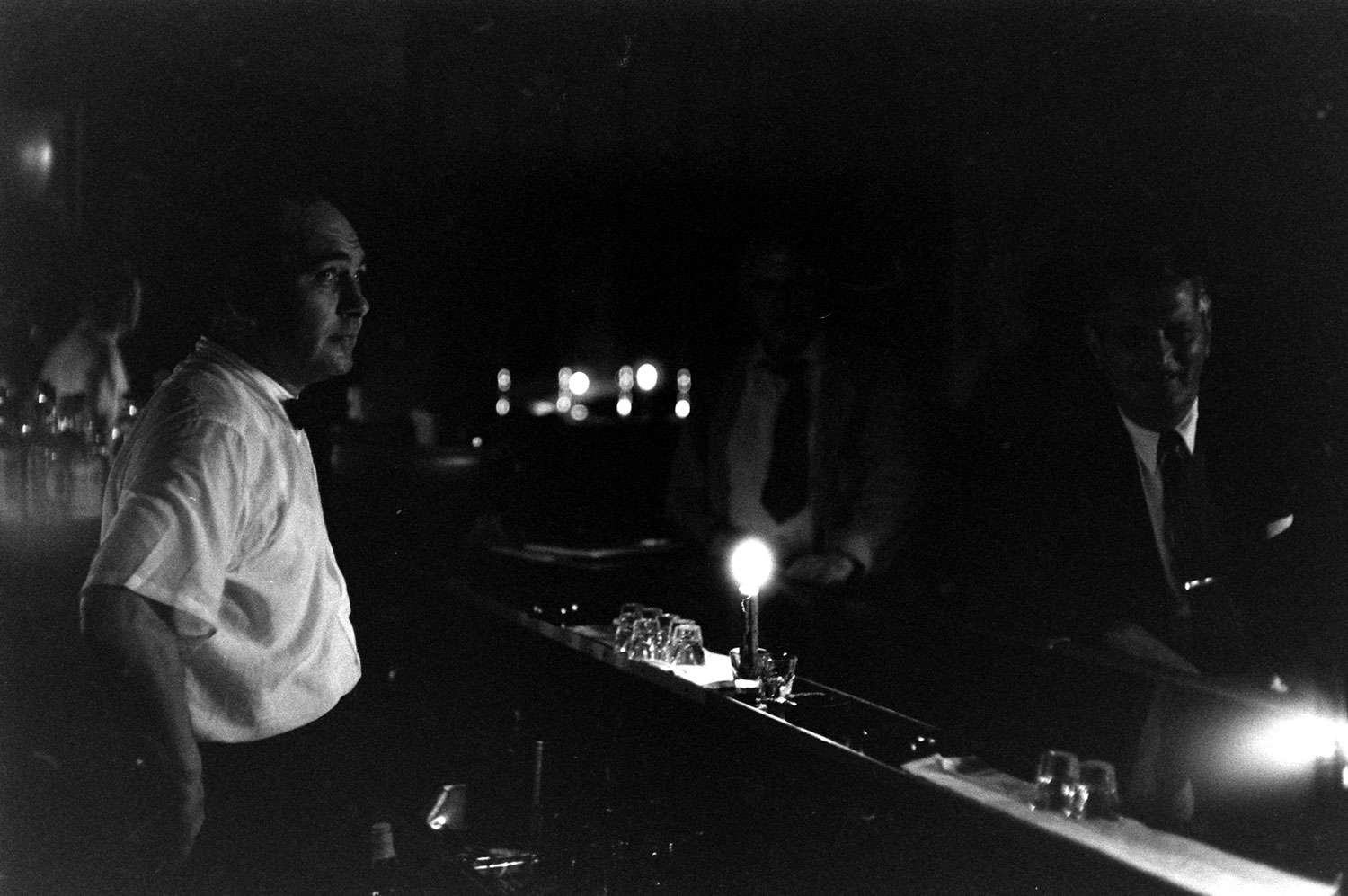

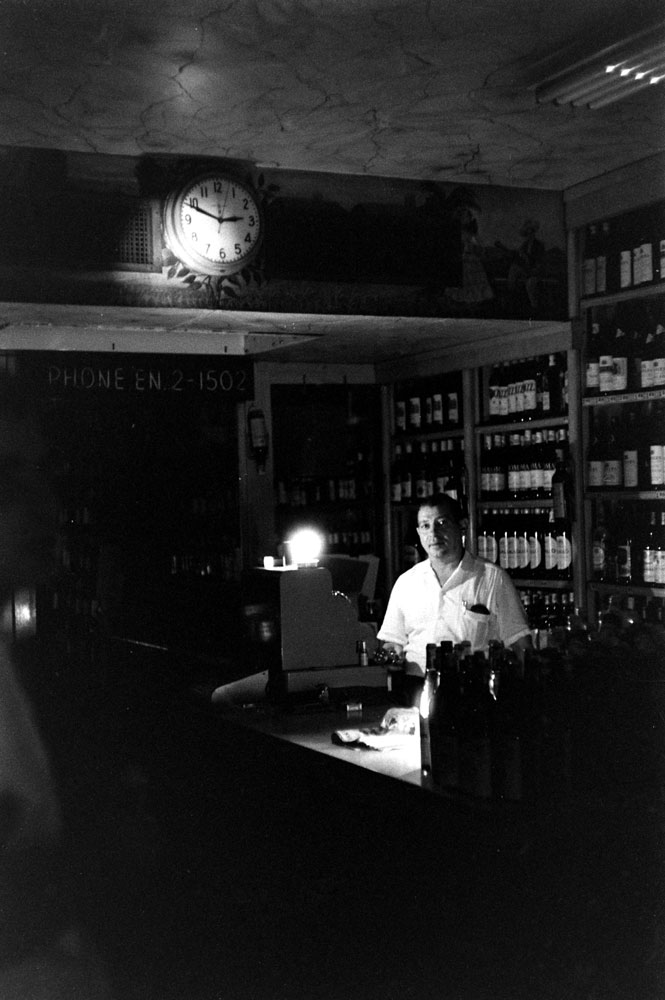

The blackout that hit New York on this day, July 13, in 1977 was to many a metaphor for the gloom that had already settled on the city. An economic decline, coupled with rising crime rates and the panic-provoking (and paranoia-inducing) Son of Sam murders, had combined to make the late 1970s New York’s Dark Ages.

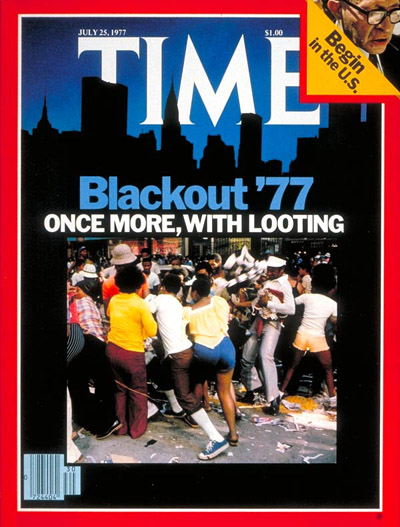

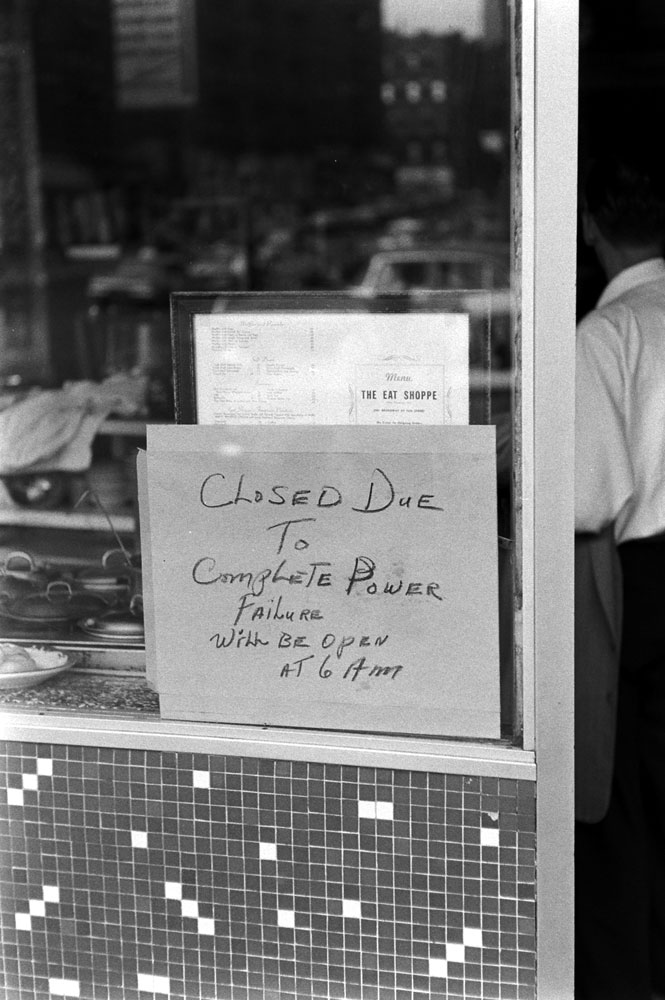

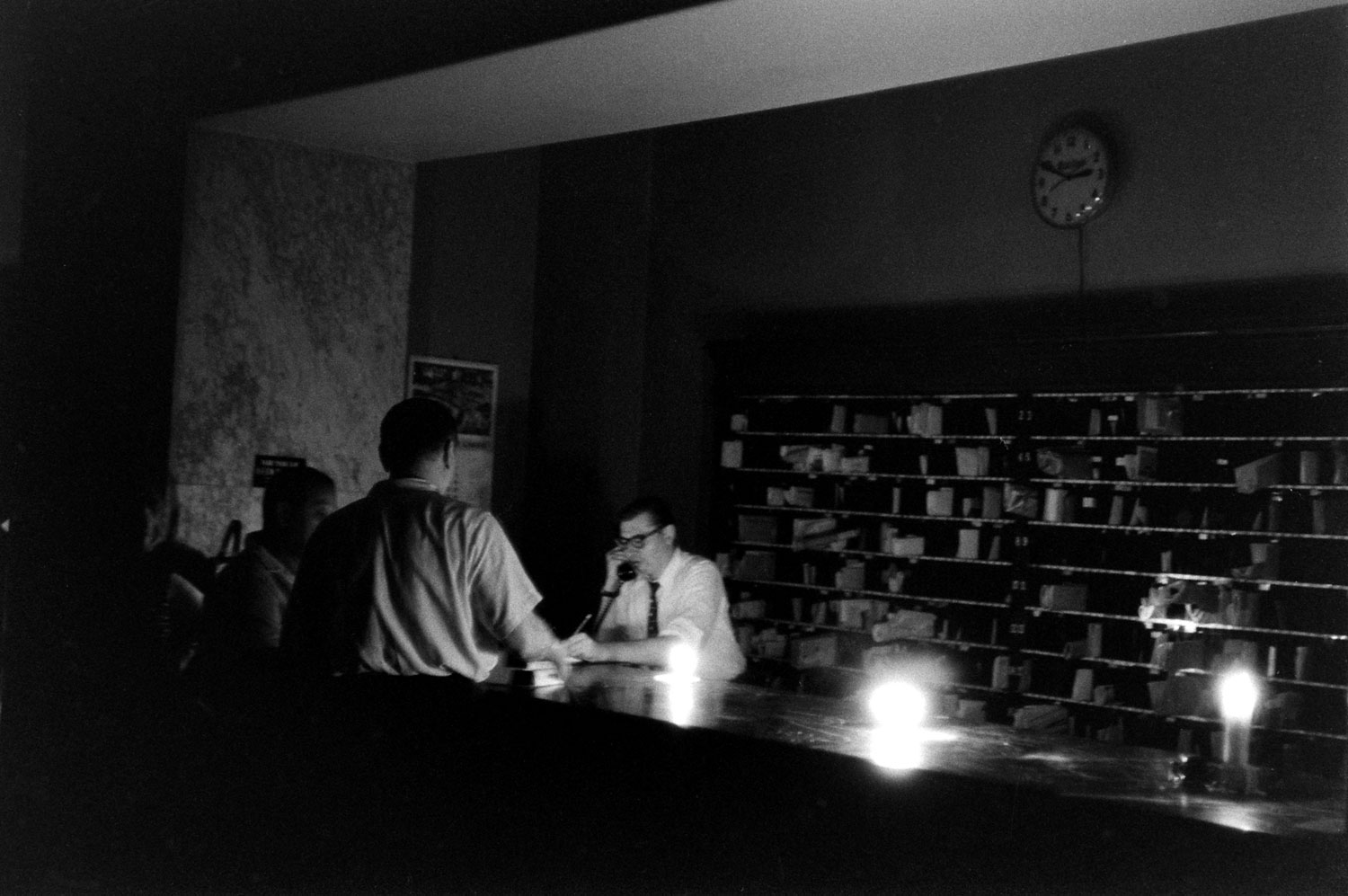

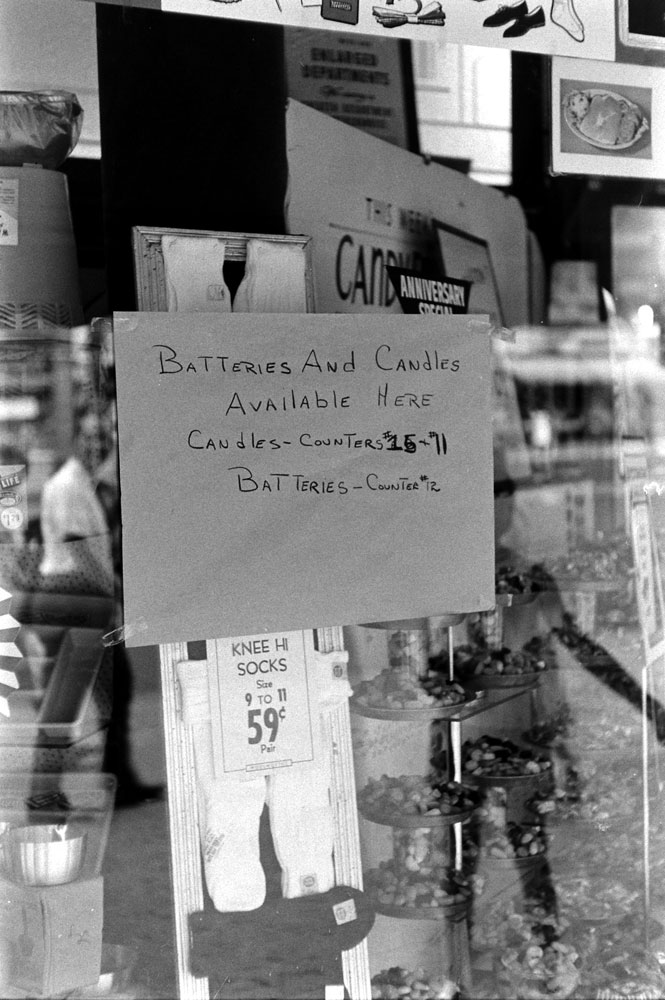

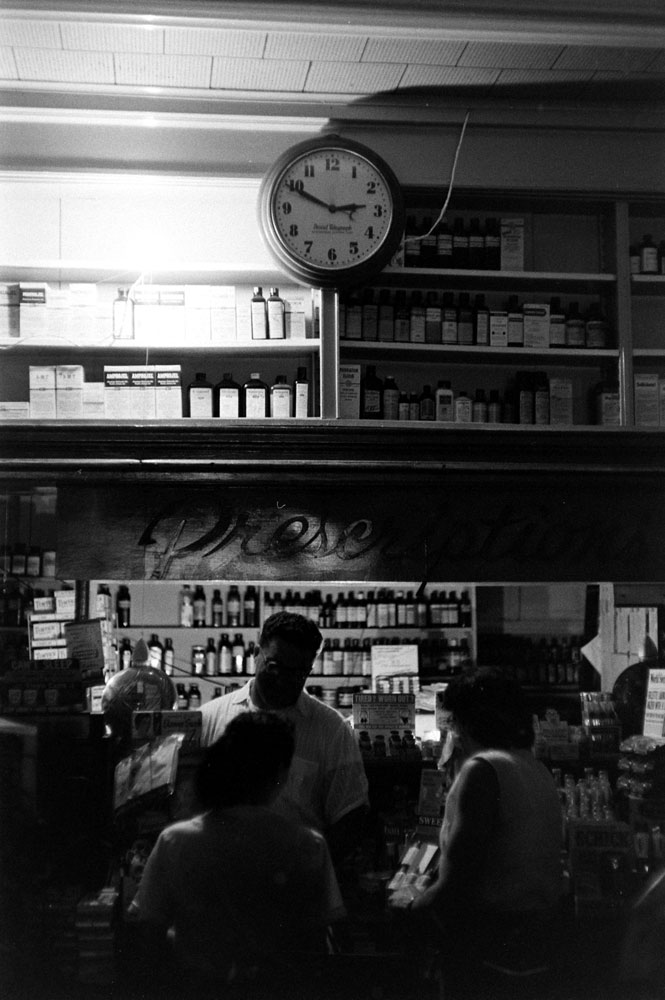

Then lightning struck, and the city went dark for real. By the time the power came back, 25 hours later, arsonists had set more than 1,000 fires and looters had ransacked 1,600 stores, per the New York Times.

Opportunistic thieves grabbed whatever they could get their hands on, from luxury cars to sink stoppers and clothespins, according to the New York Post. The sweltering streets became a battleground, where, per the Post, “even the looters were being mugged.”

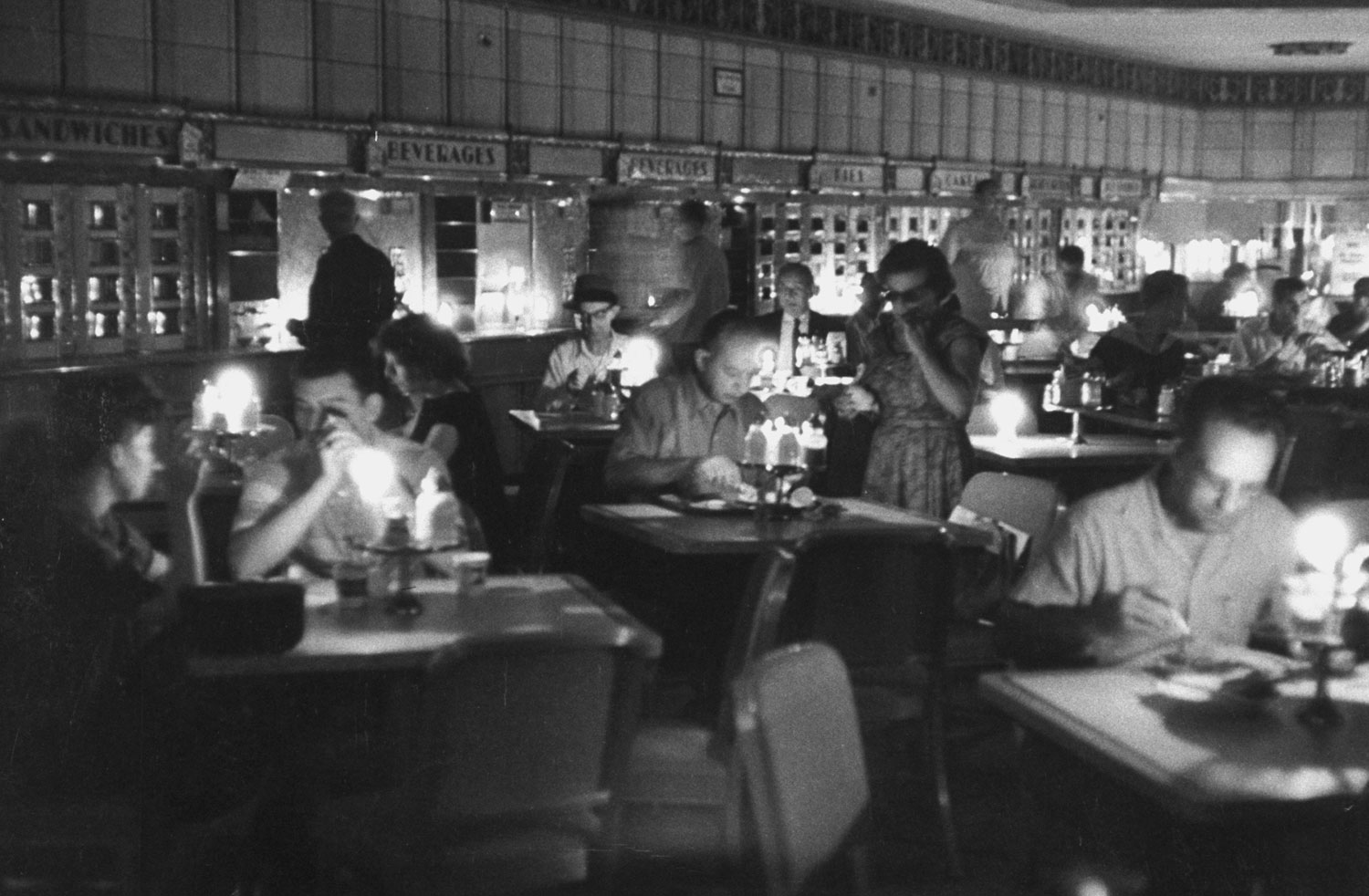

The mayhem of 1977 came as a night-and-day contrast with New York’s previous citywide blackout, in 1965. The earlier outage affected far more people (25 million, spanning New York and seven other states, plus two Canadian provinces, compared to the 9 million people in New York and its northern suburbs who lost power in ’77, per TIME). Yet the effects were dramatically, devastatingly different. As TIME put it, the 1977 blackout left the city powerless in terms of electricity and also powerless to stop the people who seized the opportunity to riot. “They set hundreds of fires and looted thousands of stores,” the magazine noted, “illuminating in a perverse way twelve years of change in the character of the city, and perhaps of the country.”

One TIME editor remarked that the tenor of the blackout had more in common with the 1964 Harlem race riots than with the 1965 blackout, which had been generally seen as an example of the city’s resilience. Now it seemed as if New York had set itself to auto-destruct. TIME noted how news media outside the city characterized the crisis:

Sample headline from the Los Angeles Times: CITY’S PRIDE IN ITSELF GOES DIM IN THE BLACKOUT. Newspapers abroad also focused on the looting. A headline from Tokyo’s Mainichi Shimbun: PANIC GRIPS NEW YORK; from West Germany’s Bild Zeitung: NEW YORK’S BLOODIEST NIGHT; from London’s Daily Express: THE NAKED CITY.

The blackout ultimately shone a spotlight on some of the city’s long-overlooked shortcomings, from glaring flaws in the power network to the much deeper-rooted issues of racial inequality and the suffering of the “American underclass,” as TIME dubbed it. Some saw the worsening circumstances — and institutional neglect — of this group of people as the key to the differences between the two New York blackouts. The ’77 blackout presented a rare opportunity for the powerless minority to suddenly seize power, TIME concluded, quoting the head of the National Urban League as saying, “[The underclass] in a crisis feels no compulsion to abide by the rules of the game because they find that the normal rules do not apply to them.”

Read TIME’s cover story about the blackout, here in the archives: Night of Terror

Lights Out New York: The 1959 Blackout

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com