The Season 5 finale of Game of Thrones, a body-count extravaganza even by the HBO series’ carnivorous standards, has boosted an unusual form of protest: sympathy for the ice zombies. Angry fans have taken to Twitter to declare that they are now rooting for #TeamWhiteWalkers, the undead army threatening to overrun the land and destroy humanity. The show’s world, Westeros, they say, is so horrible that it doesn’t deserve to survive, and besides, the White Walkers couldn’t be any worse than its current masters.

It’s an ironic lament, given that the A Song of Ice and Fire, the multivolume epic by George R.R. Martin on which the series is based, and the show have often been praised for their “gritty” and “realistic” approach to fantasy, in contrast to, say, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. In Martin’s world, virtue is not rewarded, the innocent suffer as much as the guilty, base motives are far more common than noble ones, and life’s seamy underside—from grisly violence to prostitution—is unflinchingly portrayed. But can the grittiness of Thrones be too much of a good thing—and are we wrong to equate “grim” with “realistic”?

When the series is criticized for excessive brutality and sexual violence, the standard defense is that it is portraying a fantasy version of late medieval Europe, a society not known for its humane or egalitarian attitudes. Yet historians say that life in medieval European societies, however unpleasant by modern standards, generally wasn’t quite as nasty, brutish, and short as in Martin’s Westeros (even making allowances for its wartime status). No feudal house of medieval Europe had a flayed man on its banners, as House Bolton does in Westeros. No medieval religion practiced human sacrifice, as Melisandre’s cult of the “Lord of Light” does. Monsters such as Joffrey Baratheon, Gregor Clegane and Ramsay Bolton certainly existed, but their relative frequency in the Game of Thrones cast of characters is more a matter of artistic choice than (pseudo-)historical accuracy.

Westeros also seems largely bereft of the things of lasting value created by medieval and early-Renaissance European civilization. The War of the Roses, the prototype for the series’ War of Five Kings, took place in the second half of the 15th Century, an era that also saw a remarkable flourishing of art, culture, and knowledge. Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli were starting their careers in Italy, Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales were published in England, the library at Oxford was founded, and the printing press, invented around 1440, turned books from the province of scholars and clerics into a pleasure for much larger audiences, with first-time printings of earlier medieval masterpieces as Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, and the works of Plato and the first treatise on astronomy. The 15th Century also had mystics such as Margery Kempe and pioneering humanist philosophers such as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

In earlier centuries, too, the brutality and squalor of medieval life coexisted with remarkable creativity, pursuit of knowledge, and spiritual aspirations that were about faith and charity, not fanaticism. Compare Martin’s saga and its HBO incarnation to Ken Follett’s 1989 historical novel Pillars of the Earth, and the 2010 cable miniseries based on it. Pillars, like Game of Thrones, deals with an internecine war for the throne and portrays plenty of wanton violence. But it also has leading characters passionately devoted to the construction of a great cathedral, which the miniseries’ last shot shows in modern times to emphasize that their quest endures. Meanwhile, on Game of Thrones, one character who had a visible passion for knowledge—Stannis Baratheon’s daughter Shireen—met a horrible death this season, burned at the stake in a fruitless sacrifice.

Something else missing from the world of Game of Thrones is civic discourse. While the feudal social order was authoritarian and often harshly oppressive, it also allowed for a constant process of negotiating the liberties and immunities of different classes. The Magna Carta, whose 800th anniversary fell on the day after the season finale, was one of many medieval charters limiting the powers of rulers and defining the rights of subjects. Of course, too often—especially in times of war—such documents offered little effective protection against the powerful, but if nothing else, they made the concept of personal rights and freedoms a part of societal values. In Westeros, the very existence of a Magna Carta equivalent seems almost unthinkable.

Perhaps Game of Thrones is fitting fantasy for a cynical time in which civic discourse is widely assumed to be a façade for power-grabbing and the notion of transcendent or enduring value is in doubt. But is a world of almost relentless brutality and grotesque sadism more realistic than fairy-tales of chivalrous knights and fair ladies?

I think the world of Ice and Fire has enough goodness to root for humanity. This isn’t a story in which all the good people inevitably turn out to have some inner rot, or turn bad given the right incentive. True, a distressing number of them are now checkmarks in the body count. But we still have Sam Tarly, a character with a hunger for learning, and his brave and loyal companion Gilly (and her baby). There are still the honorable Brienne and Ser Davos; there are Daenerys, Tyrion and friends; there are Sansa and even Theon. Perhaps in the upcoming books and seasons, we will see more of the human spirit prevailing.

But Game of Thrones, along with Martin’s saga, is still a compelling illustration of the basic truth that when fiction offers an unflinching look at the ugliness of life, it should not lose sight of the better things that are no less real—and that make survival worthwhile.

Melisandre / Rasputin

If the idea of an ambitious mystic who manipulates a gullible ruler into destroying his kingdom and legacy doesn’t ring a bell, you haven’t read enough Russian history. While much of the source material for Game of Thrones comes from medieval Europe, Martin may not draw exclusively from that era. And Melisandre seems to take after Rasputin, who held great influence over Tsar Nicolas II and his wife, Alexandra, just before the Russian Revolution. Rasputin was a Russian mystic who first gained the confidence of Tsarina Alexandra and then the Tsar himself, thanks to his ability to ease the suffering of their son Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia. Just like Melisandre, Rasputin encouraged the Tsar to lead his armies in battle—in World War I, another wintry hellscape—which proved to have disastrous consequences for the Tsar. Eventually, partly because of the corrosive effect of Rasputin’s influence, the entire family was murdered in the Russian Revolution. One big difference is that Rasputin made the Tsar’s son Alexei feel better, while Melisandre condemned Stannis’ daughter Shireen to death.

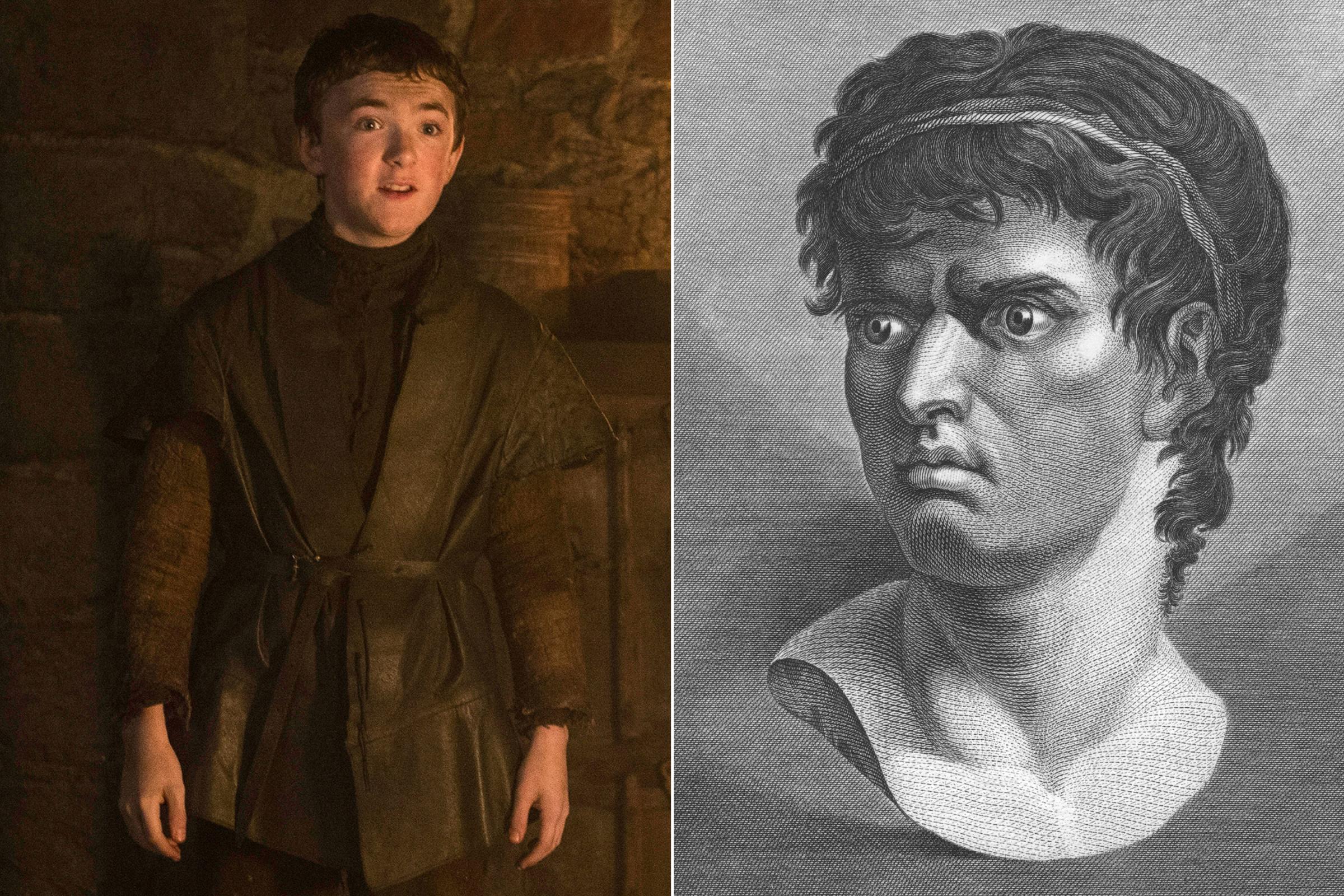

Olly / Brutus

Jon Snow’s shocking murder bears a striking resemblance to Julius Caesar’s. Both were stabbed repeatedly, with each knife held by a different colleague. And just as it was for Caesar, Jon receives his final blow from one of the people he trusted most: Olly, the farm boy who watched the Wildlings slaughter his parents. Olly had been Jon’s protege, just as Brutus had been Caesar’s trusted friend (at least in Shakespeare’s retelling of the assassination) but both turned murderous after their mentors assumed too much power. In Jon’s case, it was the unilateral decision to let the Wildlings south of the Wall; in Caesar’s case, it was when he named himself “dictator in perpetuity.” No wonder everyone seems to be tweeting, “Et tu, Olly?”

Fighting Pits / Colosseum

In Mereen, and elsewhere in Slavers’ Bay, slaves fight to the death for cheering audiences and a chance to gain their freedom. In Ancient Rome, slaves and fighters fought as gladiators in the Colosseum for the same reasons. The fighting pits even look like the Colosseum, down to the subterranean chambers where the fighters wait for their turn.

Loras Tyrell / King Edward II of England

Loras Tyrell and King Edward II of England were both handsome, both considered excellent fighters, and both brought down by their scandalous affairs with men. Loras Tyrell was imprisoned by the High Sparrow for his fooling around. King Edward II was widely rumored to be romantically involved with his squire and companion Piers Gaveston, despite his marriage to Isabella of France, who is remembered as a cruel but beautiful queen. (Remember that Loras was betrothed to Cersei, who is nothing if not beautiful and cruel.) Edward II’s romance with Gaveston strained his relationship with the barons he ruled and caused tension in his marriage to Isabella–Gaveston reportedly even wore jewelry that Edward had given her. These factors, along with a series of wars and invasions, probably led to Edward’s abdication in 1327.

Valyria / Pompeii

Remember when Jorah Mormont took Tyrion Lannister through that spooky ghost city full of Stone Men during the kidnapping-slash-road trip? That was Valyria, the capital of the Valyrian Freehold, once the most powerful civilization in the world and ancestral home of the Targaryens and their dragons. Valyria had been destroyed hundreds of years before the story begins, in what looks like it must have been a massive volcanic event. Tyrion recites a poem about that disaster, known as the Valyrian Doom, as they row through the ruins: “They held each other close and turned their backs upon the end / the hills that split asunder and the black that ate the skies / the flames that shot so high and hot that even dragons burned.” It’s impossible to ignore the comparison to Pompeii, an ancient Roman city that was completely destroyed when nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted, killing almost every inhabitant of the city. Even the imagery of citizens who died as they “held each other close” is eerily similar to the bodies found during the excavation of Pompeii. No dragons, though.

Shireen / Iphigenia

O.K., so this one’s not technically history—but you still might learn about it in history class. Stannis Baratheon isn’t the first warrior-king to sacrifice his daughter to win the favor of the gods. In Greek mythology, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia in order to implore the Gods to change the wind patterns so he can sail for Troy to fight the Trojan War. Both Stannis and Agamemnon are told by prophets (or, in the case of Game of Thrones, it’s Melisandre) that the only way to ensure victory is to sacrifice their daughters, and both Shireen and Iphigenia are unaware of their fates. And in both stories, the daughter’s sacrifice leads to the demise of her mother: in Game of Thrones, Shireen’s mother Selyse hangs herself after witnessing her daughter’s death, in Greek mythology Iphigenia’s mother Clytemnestra murders Agamemnon for killing their daughter, and is then murdered by her own son as revenge.

Cersei / Jane Shore

Cersei’s hideous walk of shame in the Season 5 finale wasn’t completely made up– that kind of public humiliation was a common medieval punishment for women who were found guilty of adultery or other sexual transgressions. But Martin has said that Cersei’s particular penance was inspired by Jane Shore, the mistress of King Edward IV of England who was forced to walk the streets as a harlot after Richard III took power. Richard was likely punishing Shore for conspiring against his rise more than having sex out of wedlock, but he still forced her to walk around in her undergarments, with bare feet, in 1483. In other circumstances, medieval women found having sex with someone who wasn’t their husband were forced to do the walk naked, as Cersei did.

Read more about the link between Cersei and Jane Shore here: The True History Behind Cersei’s Game of Thrones Walk of Shame

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com