For the fifth time in seven years, a state high court has ruled that employers have the right to fire employees who use medical marijuana.

In a decision released today, the Colorado Supreme Court found that Dish Network, the national satellite TV provider, did not act illegally when it fired Brandon Coats, a Denver-area call center rep, in 2010 after Coats tested positive for marijuana. Although Colorado law permits the use of medical marijuana, the court ruled that Dish was within its rights because pot remains illegal under federal law.

Although the case is limited to Colorado, the court’s decision has national ramifications. Previous cases in California, Montana, Oregon, and Washington all swung for the employer, but the Colorado case was seen as the best chance for a ruling in favor of medical marijuana patients–and not just because of the state’s embrace of medical and recreational pot.

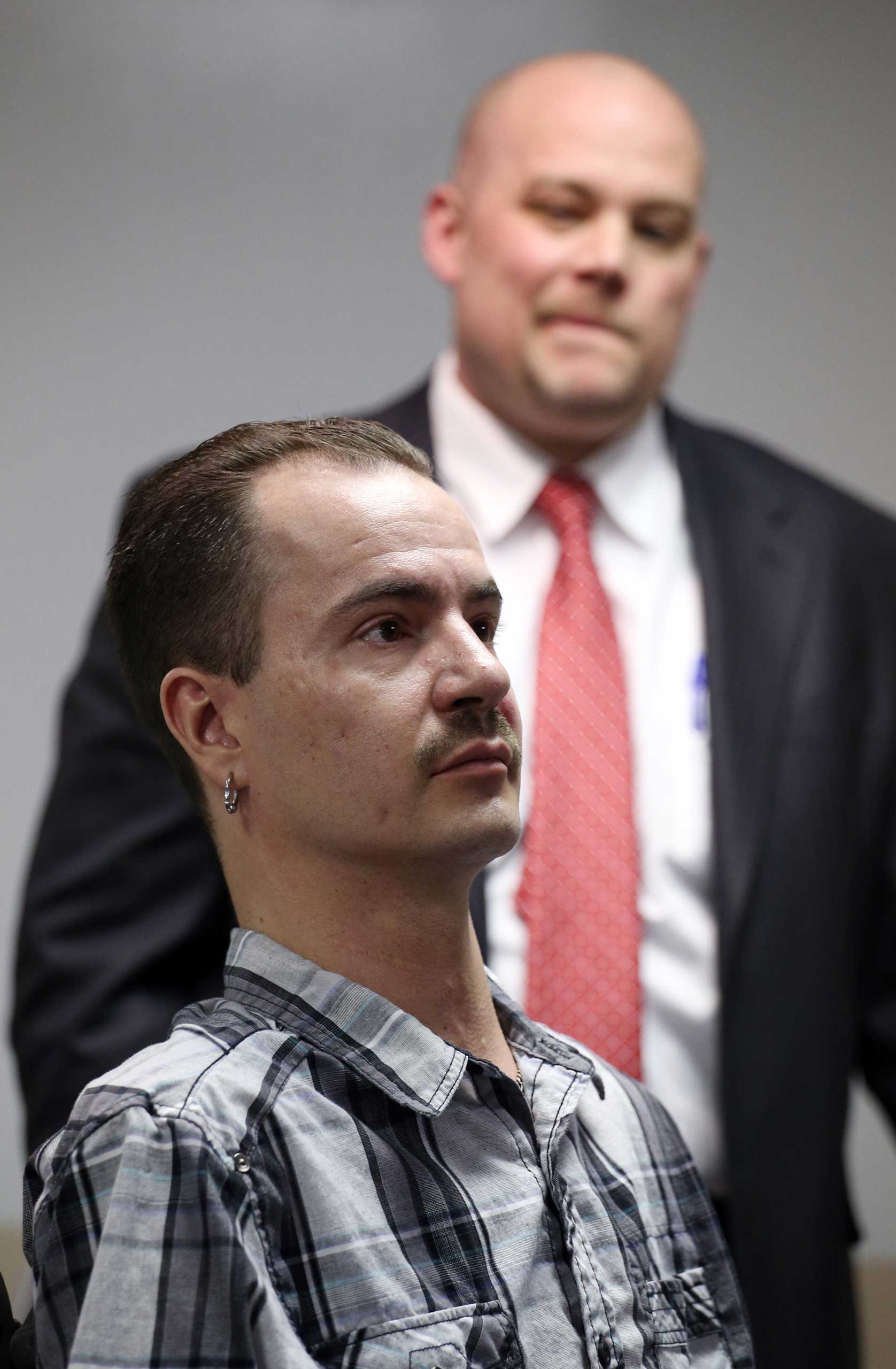

For one, Coats was a particularly sympathetic plaintiff. The 35-year-old has been quadriplegic since a car accident at age 16 and has been considered a model employee since being hired by Dish in 2007. In 2009, Coats obtained a state-issued license and began using medical marijuana at night, after work. “I take it at home every night,” he said in an interview last year. “It helps me sleep. I wake up with less stiffness, and it quiets my spasms all through the next day.” By sleeping off the psychoactive effects, he could report to work clear-headed the next day while the antispasmodic effects of the drug continued to calm his system. In 2010, Coats was selected for a random drug test. He came up positive for marijuana–as he told his boss he would–and was fired soon after for violating Dish’s anti-drug policy.

Coats and his lawyer, Michael Evans, contested the firing in state court. Similar marijuana patients in other states had sued–and lost–by citing the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), or the state’s medical marijuana statute. Colorado is one of 23 states and the District of Columbia that allow medical pot. These laws allow a patient to cite medicinal use as a legal defense against criminal marijuana charges, a practice known as “affirmative defense.” But State courts have declined to expand the statutes to include immunity from firing. In fact Colorado’s medical marijuana law, like those in many states, holds that employers are not required “to accommodate the medical use of marijuana in any work place.”

The odds were against Coats. So his lawyer tried a novel approach. Colorado has a “lawful activity” statute that prohibits employers from discriminating against employees for engaging in legal off-duty conduct. Coats’ marijuana use, Evans argued, was exactly that: legal and off duty. Dish replied that Coats’ medical pot, though consumed off-duty, was nevertheless active on-duty. “Coats freely admits that his [medical marijuana use] affected him while at work, even claiming that it altered his job performance,” the company said.

In effect, a drug Coats said helped him perform better at work was the reason he was fired.

This is the kind of Alice in Wonderland logic born of a circumstance in which marijuana is simultaneously a state-legal medicine and a federally illegal drug. (Because Coats’ firing happened in 2010, Colorado’s 2012 legalization of recreational pot had no bearing on the case.) But Dish’s argument wasn’t as crazy as it might sound. Steroids improve a baseball slugger’s job performance. Cocaine can increase a factory worker’s short-term productivity. To maintain a drug-free workplace (or at least a federally illegal drug-free workplace), Dish was willing to sacrifice the career of one employee–even one as sympathetic as Brandon Coats.

In the end, Coats’ case, like those before his, couldn’t overcome the inexorable power of federal law. Colorado’s “lawful activity” statute, the state high court ruled, did not extend its protections to activities considered illegal under federal law. In a released statement, Dish Network officials said they were pleased with the decision: “As a national employer, Dish remains committed to a drug-free workplace and compliance with federal law.”

The ruling, said Evans, means that “most employees who work in a state with the world’s most powerful medical marijuana laws will have to choose between using medical marijuana and work.”

Coats described himself as “very disappointed” by the decision. “If we’re making marijuana legal for medical purposes we need to address issues that come along with it,” he said.

The latest ruling means that those issues won’t be solved at the state level anytime soon. The barrier is clear: Little will change unless the federal government evolves its own position on marijuana.

Barcott is a journalist who has contributed to the New York Times, National Geographic and other publications. His new book “Weed the People, the Future of Legal Marijuana in America,” from TIME Books, is now available wherever books are sold, including Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com