Spoilers for Game of Thrones follow, of course:

The second episode of Game of Thrones season 5 began with Arya Stark coming to Braavos and reciting a list. “Cersei, Walder Frey, The Mountain, Meryn Trant.” In “Mother’s Mercy,” the season 5 finale, her list got one name shorter, as she mastered the game of faces well enough to stab Syrio Forel’s killer Trant to death.

Cross another off the list. Write a few more down. Does payback feel good? And does the feeling last?

Everyone else has a list too–other characters and those of us watching the show–and those lists only got longer in season 5, as atrocities multiplied and injustices mounted. And though the finale left us with a higher-than-usual number of cliffhangers (or Wall-hangers, as the case may be), it was also run though with characters facing consequences. But they didn’t offer clear, unambiguous satisfaction. Because as “Mother’s Mercy” demonstrated, consequences may come, but not necessarily for the right reasons, or to the right people, or for their worst sins.

Let’s start in the North, with Stannis Baratheon in the snow. For all the million times we’ve heard Stannis described as Westeros’ greatest military strategist, we’ve mostly seen him losing–except against an overpowered Wildling army–and in the end we saw him swallowed up, in a sweeping overhead shot, by the Bolton cavalry as he commanded an army not big enough to besiege a snow fort.

Stannis’ last mistake was not one of strategy so much as morality and emotional intelligence. He saw his sacrifice of daughter Shireen as necessary to win the North and achieve his destiny, but it looked to most of us like a dealbreaker. Turns out soldiers aren’t crazy about following a filicidal, monomaniacal religious fanatic into battle, either: consequences! He’s left to slump against a tree (a kingly moment of stoic desolation as rendered by Stephen Dillane) and await the death blow from Brienne of Tarth. We never see the blow land, though, and it’s retribution not for Shireen at all but for his brother Renly.

And it gets more complicated, because Stannis had been set up both as deserving of consequences and as an agent of consequences we wanted to see–he was marching to war, after all, against Ramsay Bolton. Badass as Brienne may be, she’s not likely to overthrow the Boltons singlehanded, which left Theon and Sansa to take a leap of faith off the wall of the castle. (Again, if we don’t see someone land in a bloody spray a la Myranda, I’m going to assume they’re alive until proven otherwise.) Consequences are satisfying–until they have consequences of their own.

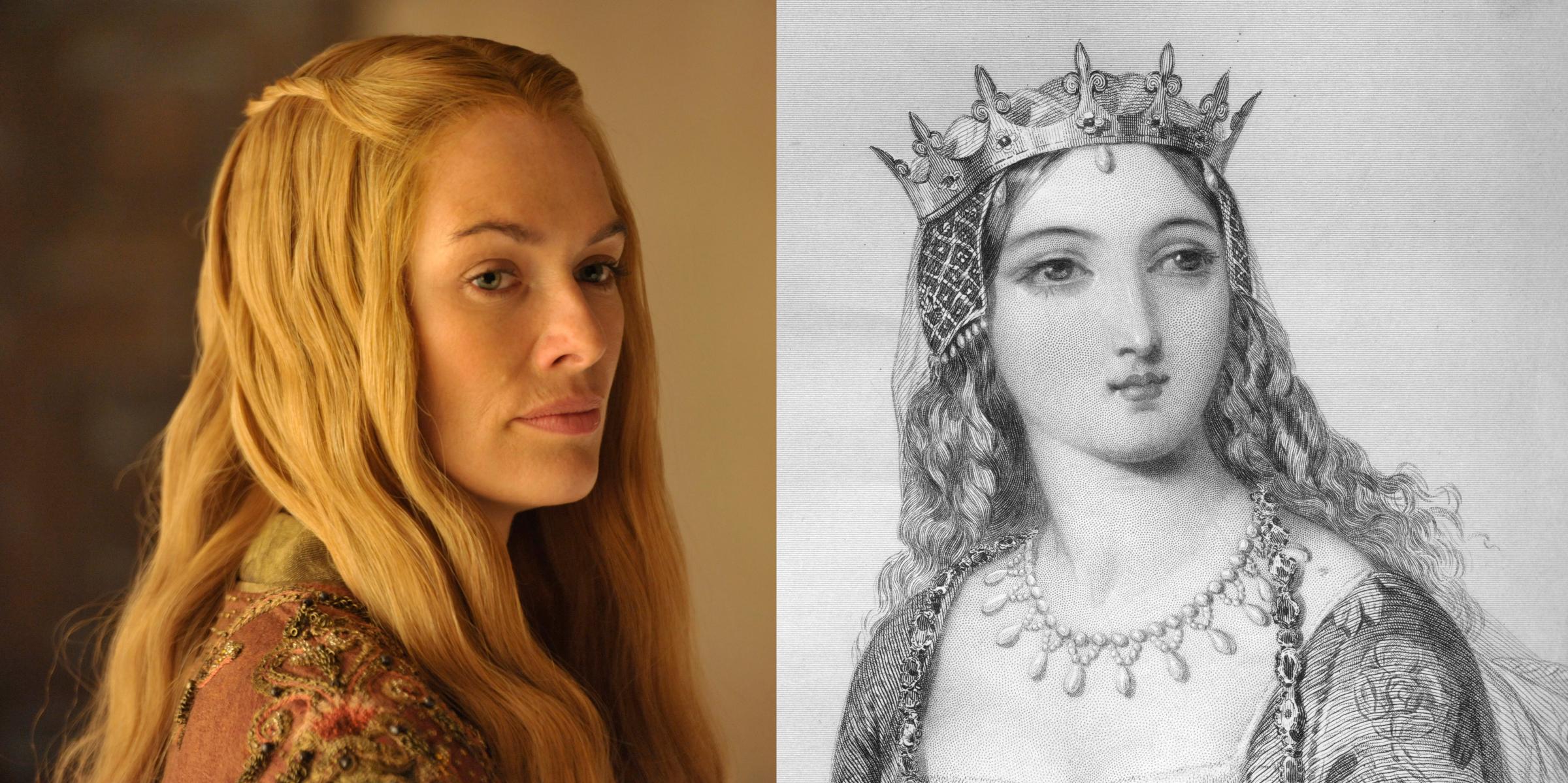

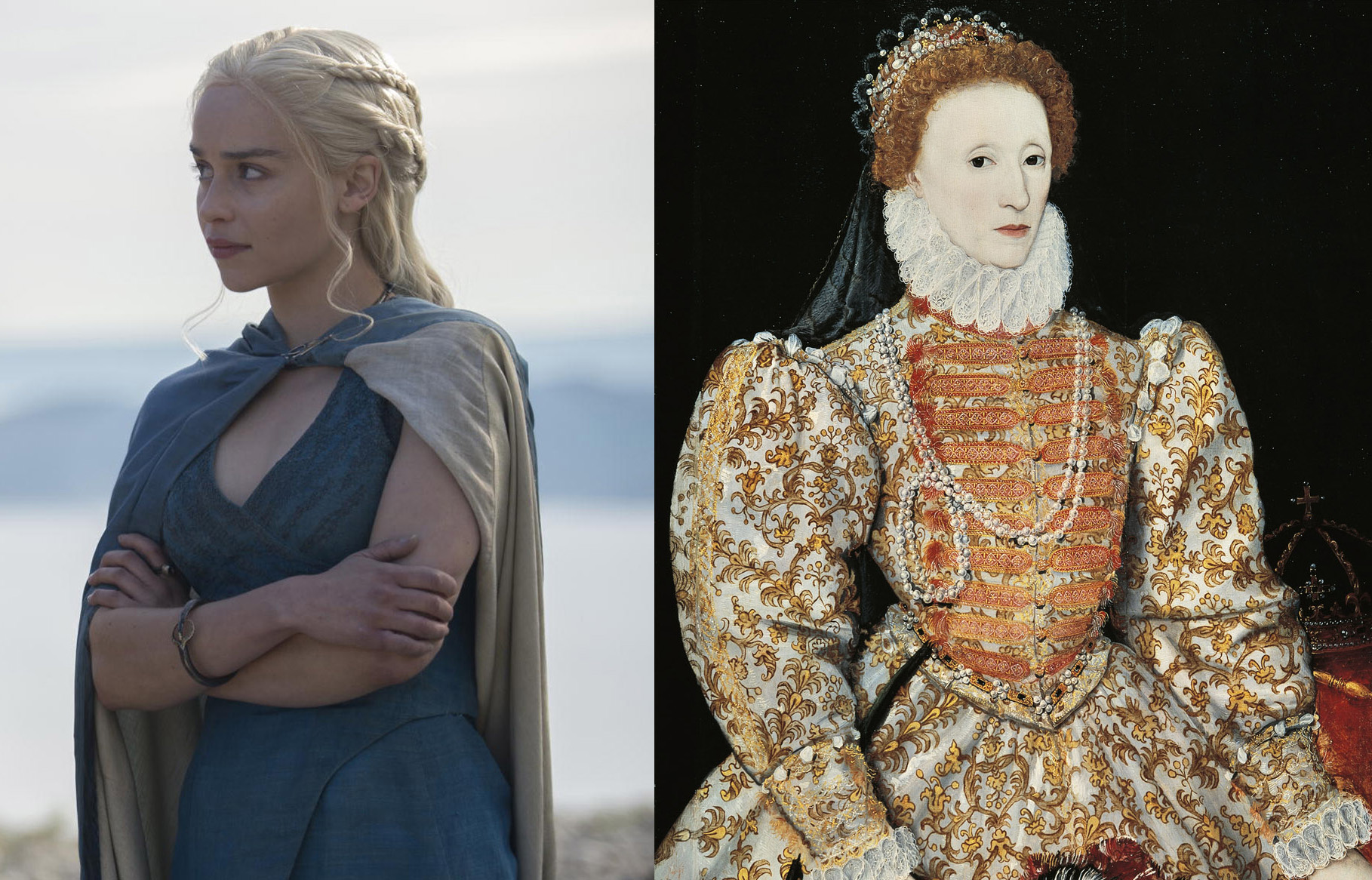

See The Real-Life People Who Inspired Game of Thrones Characters

We saw more imperfect consequences in the episode’s most harrowing and effective storyline, the punishment of Cersei Lannister. Who among us hasn’t wanted to see Cersei punished for something–the persecution of the Starks, the effective coup against King Robert, the unjust downfall of Tyrion, for starters? Sleeping with her cousin Lancel, however, was probably not high on any of those lists.

Yet that was the crime she was done in for–and, really, for the crime of being a woman, the target of a religious reformation that is populist, concerned for the poor, but also deeply misogynistic. It’s not a stretch to call her punishment a slut-shaming. (The commoners yelling “Slut!” while a septa chanted “Shame!” is your tipoff.)

Fine, you might say: and they got Capone for tax evasion. Should it matter that Cersei suffered consequences, but in the wrong way for the wrong thing? It matters morally–I would bet even Cersei-haters felt sympathy with her by the end of that march–but it also matters practically. The last we see her, she’s cradled in the arms of Ser Robert Strong, the Frankenguard whom Qyburn promises will vanquish all her enemies. Now we have a committer of legitimate wrongs herself legitimately wronged, motivated and empowered to strike out in kind. (And this before she knows that the poisoned body of her only daughter is sailing home to her.) Does anyone think only the High Sparrow will suffer for it?

All that led to the episode’s stunner of a conclusion, in which Jon Snow suffered a consequence none of us asked for–but that the episode invited us to see from the standpoint of the vengeful as well. To us, of course, Jon is among the closest to a legitimate hero Game of Thrones has, self-sacrificing, principled, able to risk body and soul for a larger good. But to Olly? He’s the man who took in the very people who butchered his parents before his eyes–a loss no better to him, after all, than the sacrifice of Shireen was to us. Think how badly you wanted payback against Stannis: then make yourself an orphan boy, with your new Night’s Watch brothers echoing that Jon is a traitor–and put a knife in your hand.

So good intentions and payback and the certitude of righteousness end, with Jon’s eyes going dim as he bleeds out into the snow. (Dead? Actually dead? As a reader of the source books, I know no more than you do of Jon’s fate, but I guess the fact that I’m mentioning his death, or “death,” this far down in the review is evidence of how permanent I think it is, no matter what Kit Harington says for now.) It’s the biggest, but by no means only, “To Be Continued” Benioff and Weiss stuck on the end of this season, as Arya went blind, Dany met the Dothraki again, and Daario and Jorah went hunting after her a la Aragon, Gimli and Legolas in The Lord of the Rings. (Though, of course, this time the search party left the dwarf behind.)

Jon aside, I’m guessing more of these characters make it through than we suspect, lest the only ones left playing the game of thrones by series’ end will be Olenna Tyrell and Hot Pie. So what to make of season 5? More than even more serial dramas, Game of Thrones really is telling a single story–which means that, to me, the series always seems greater as a whole than it does in any individual year.

That said, we can assess separate storylines. Dorne turned out to be a viper holding a giant goose egg in its teeth. On the other hand, the season did a particularly good job bringing together the disparate storylines in the North with emotional power, though it involved the most changes from the books and the biggest controversies. (Whether you felt Sansa should have been sent off with Ramsay in the first place, the show took the repercussions of her rape seriously, and allowed her to build strength even through being terrorized.)

Meereen was a mixed bag but at least efficiently handled, while–though this may partly be recency bias from the powerful Cersei scene–the political and religious machinations in King’s Landing paid off better than I expected. Meanwhile, the season did an elegant job building its world and mythology, in sequences like Jorah and Tyrion’s awe-inspiring journey through Valyria. (And Braavos? Let’s be honest, I’d be grateful for Arya scenes even if she’d spent the whole season learning to shuck oysters.)

But it wasn’t pretty, and as I wrote earlier, I can entirely understand anyone who decides it’s too relentlessly punishing for them. Because it’s a single story, Game of Thrones is not the kind of series that can end a season with triumphs for the good guys, before introducing new challenges for them the next year.

You know the saying about three-act drama, where you get your characters into a tree in the first act, throw rocks at them in the second, then get them down in the third? In Game of Thrones‘ seven acts (or eight or however many it takes), it gets them in a tree, throws rocks, then throws anvils and wildfire and death icicles, and then the tree comes to life and eats some of them. (Unless a character is lucky enough to become a tree.)

But I would distinguish between Game of Thrones‘ being a dark series and its being a hopeless one. And I saw cause for hope in the season’s best episode, “Hardhome,” though ironically it ended in the defeat and rout of a mission led by a character who is now (allegedly) dead. In that standoff with the Night’s King and his undead army, we saw the reminder that there is an actual greater good–and a greater bad that threatens all life, Lannister, Targaryen and Stark alike. There is something more to the story than hoping that the lesser evil ends up living in the Red Keep.

So I believe, or I hope, anyway, there there is a bigger game afoot, something more in the end than unsatisfying vengeance against terrible people by compromised people–something more than monsters fighting worse monsters. (That’s why, though it seems like a potential digression, I’m intrigued by the idea of Tyrion and Varys running Meereen, seeing if the answer for the beleaguered city is not dragons or harpies but simple competent governance.) I can’t know that–at this point, nearly every character’s story has ended where the books now are, or passed it–but not knowing, strangely, makes me more optimistic.

It’s hard to keep sight of the bigger picture here all the time, though, what with all the injuries and atrocities. They put us in the position of the list-makers, rooting for payback and defining characters’ worth and utility in terms of what they can do to the bad guys. But maybe–call me as naive as Jon Snow–there will be a role in Game of Thrones for characters who can prove themselves not through what they do to others, but what they do for others.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com