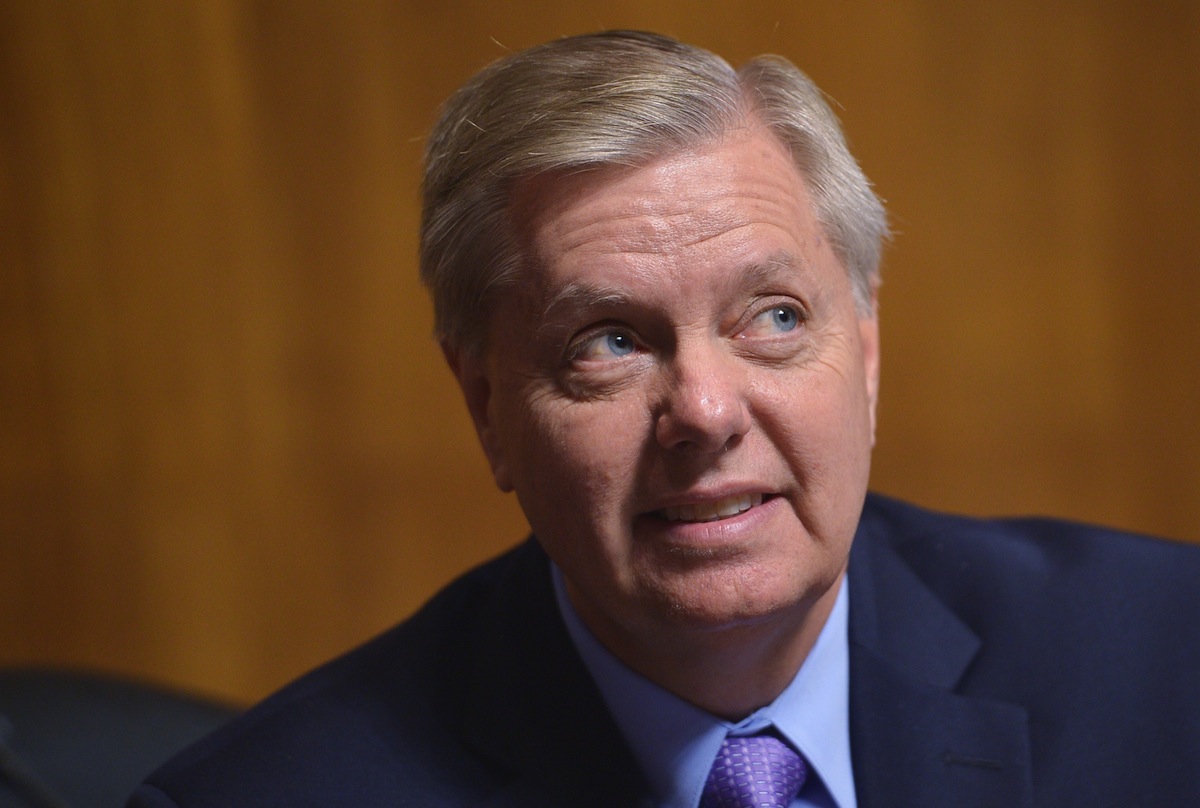

With his decision to announce his candidacy for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham has drawn the eyes of politics-watchers to his record of bucking his party on select issues.

In recent years, that has meant speaking out about the risks of climate change, backing President Obama’s Supreme Court nominations and supporting immigration reform. But that contrarianism dates back to one of his early defining moments in politics: the Monica Lewinsky scandal and the subsequent impeachment trial of President Clinton.

A former military lawyer, Graham was elected to the House of Representatives amid the 1990s tide of Newt Gingrich-led, small-government fervor. Though he often focused on issues like tax cuts in his early years in the House, he soon found himself drawing national attention for his attitude toward getting rid of Gingrich. When several GOP Congressmen attempted in mid-1997 to get themselves a new Speaker, Graham was identified by TIME as “a rebel leader”—but taking sides against Gingrich didn’t mean defying the party. Rather, he told the magazine he wanted to get across that “being conservative and mean are not synonymous.”

That tension between Graham and Gingrich continued into 1998, as the impeachment trial neared.

Graham, along with Mary Bono of California, was cited as one of two Republicans who might vote with Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee in order to prevent the vote from moving to the full House. He famously asked the rhetorical question “Is this Watergate or Peyton Place?” while dissecting the charges. Graham ended up voting for three of the four articles of impeachment, but even so he was the only Republican on the committee not to vote “aye” on all four. (The one he voted against was Article II, one of the perjury charges.)

In the end, TIME’s Margaret Carlson posited that his indecision about the vote came, perhaps, with ulterior motives. “Representative Lindsey Graham‘s early turn as Hamlet turned out to be a search for an unoccupied spot on the opinion spectrum that might land him on Meet the Press,” she wrote. “He found a ‘legal technicality’ that allowed him to vote against one article, earning him the valuable CONSERVATIVE BUCKS HIS PARTY headline in the New York Times.”

Whatever the motive, the reputation stuck.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com