It’s enough to make a campaign get on its knees and beg. Literally.

Such was the scene earlier this month at Rocket Man, a dueling pianos joint in Columbia, S.C. A top aide in former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush’s campaign-in-waiting dropped to one knee and asked a respected South Carolina operative to reconsider her decision to join rival Mike Huckabee’s run at the Republicans’ Presidential nomination.

Hope Walker, who most recently was the state director for the South Carolina GOP, told her suitor that she was sticking with Huckabee and there was no need for Bush to phone her. Bush communications maven Tim Miller shook his head, stood up and moved onto his next potential hire at the other end of the bar. Miller is still wooing that operative.

For GOP campaigns looking to build a payroll of experienced aides, this is the new normal: lots of courtship and many promises.

With more than a dozen—and perhaps eventually as many as two dozen—contenders at various stages of preparation for a White House bid, the fight for staff is fierce. Promises of access to the candidate, special titles and bloated salaries are the new chits for the small subset of political professionals who have run campaigns before.

And that’s before the outside groups, the super PACs and the nominally apolitical groups such as Americans for Prosperity or the League of Conservation Voters start building their teams. Those groups are ramping up their staffs and activities, fueled by donors who can give an unlimited amount of cash. In turn, it’s becoming a bidding war.

Operatives who have networks in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina stand to be the campaign’s most obvious profiteers.

“It is harder to find this time because there are so many candidates or likely candidates,” said a veteran operative to Presidential hopefuls and a current adviser to a top-tier candidate who has yet to formally enter the race. “The supply isn’t here to even meet the demands. There is a dynamic that it feels like there is a shortage of staff.”

Part of it is more than a feeling. Take New Hampshire, which is scheduled to have the nation’s first primary on Feb. 9, 2016. In non-presidential years, elections there are typically used to build a bench of talent and train them for the coming White House runs. That didn’t happen in 2014; Senate hopeful Scott Brown imported many of his aides from across state lines in Massachusetts, and gubernatorial nominee Walt Haverstein ran a lackluster race that no one wants to repeat.

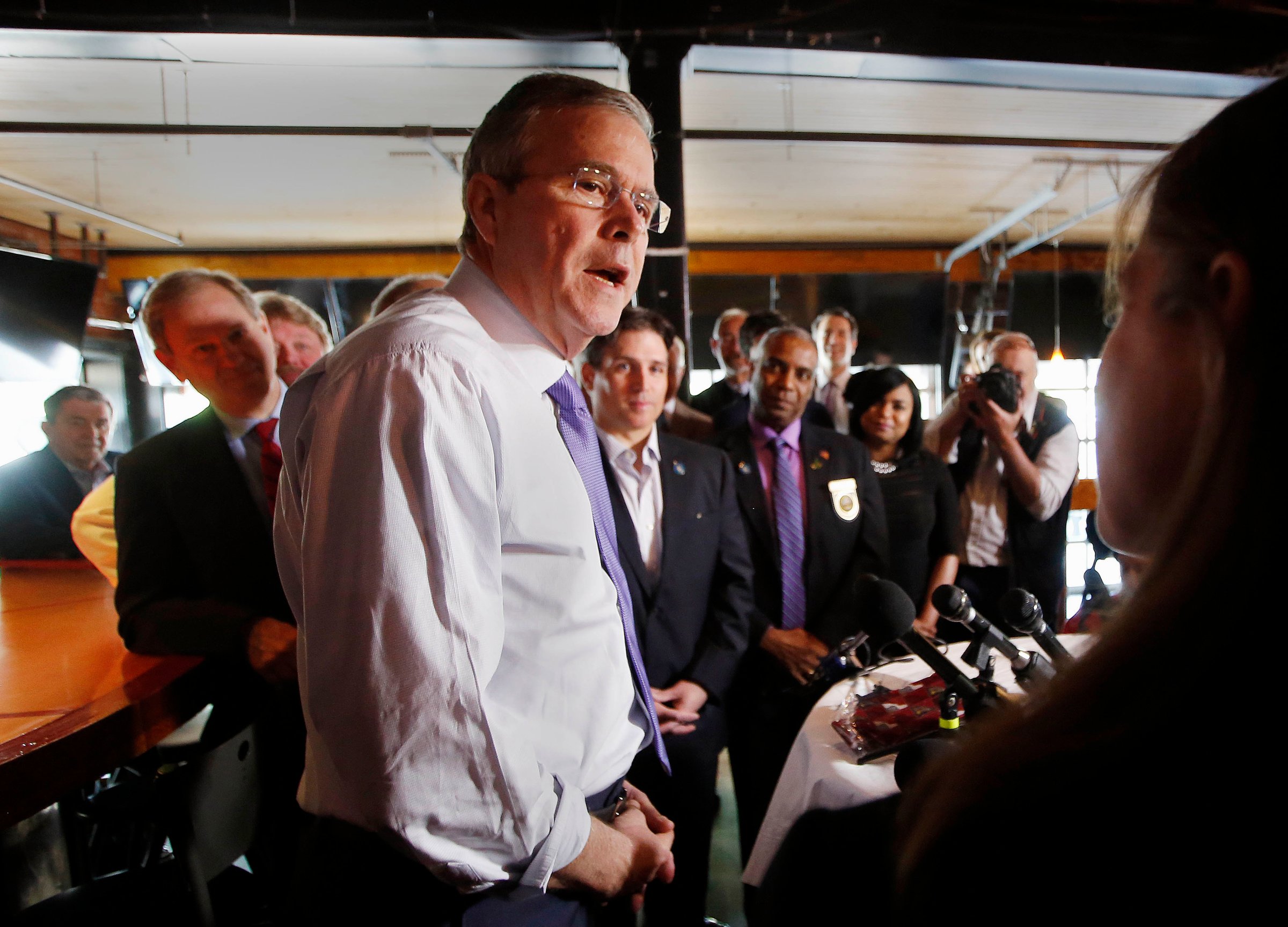

The result is what one aide calls a BYOS dynamic: Bring Your Own Staff. Miami-based Miller was at Bush’s side last week in New Hampshire on a trip to New Hampshire. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker had his Madison-based aides with him on a recent trip. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie has no plans to hire New Hampshire-based communications aides and sent a former Trenton-based adviser to New Hampshire to lay the groundwork for a potential run.

Even Sen. Kelly Ayotte had to import talent for what could be a tough re-election bid in 2016. The de facto head of the New Hampshire GOP recruited a campaign manager, Ben Sparks, from his most recent campaign helping Dan Sullivan win a Senate race in Alaska.

It is a dynamic that is playing out in the other states, and at national headquarters, where finding bodies to put into jobs is taking up a lot top campaign aides’ time.

“With the potential for 19 candidates, anyone who has a hint of a resume gets to be a political director or a state director,” said an established political adviser who has four Presidential campaigns on her resume. She, however, is sitting this campaign out despite repeated phone calls from presidential hopefuls and their staffs.

“Their pitch was: ‘Whatever you want,’” she said. She is passing even though she is leaving potentially hefty paychecks on the table. Her 2012 job paid her $10,000 a month and she figures she could have more than doubled that in 2016.

None of the declared or likely candidates has filed campaign finance reports that would indicate salary levels for the 2016 race. But among the sought-after operatives—friends to each other in non-election settings—they speculate some of the top staff hires are earning as much as $35,000 each month.

To be sure, there is money to be made Presidential politics. In late December of 2011—days before Iowa’s caucuses—then-state Sen. Kent Sorenson resigned from Rep. Michele Bachmann’s Presidential campaign to join Rep. Ron Paul’s. According to his plea deal in a campaign finance case, he received $73,000 for the defection. And that was over a move from a sixth-place finisher to a third-place candidate in 2012.

With 2016 looming, the price is only increasing. “They’re inflating the prices of these guys,” said a longtime adviser to a former governor chasing the nomination. “They know it’s a short run and they want to milk it for all it’s worth,” he added.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com