When it comes to international relations, there are many ways to change the situation on the ground. But the Chinese are trying a new one far off their coast: they are creating new ground.

It’s part of Beijing’s plan to extend its claim to 90% of the South China Sea, and now the Chinese government is ordering the U.S. and other nations to steer clear, or at least to seek permission before visiting the neighborhood.

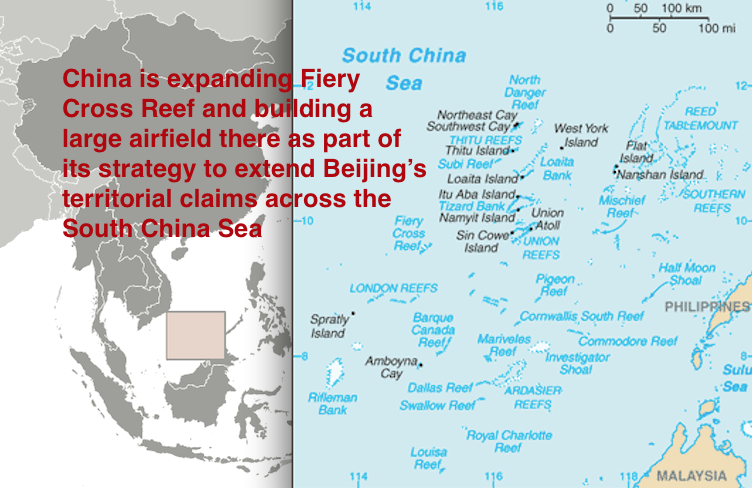

Sure, it’s not a whole lot of land. China has dredged about 2,000 acres of once-submerged sand to enlarge five islets in the Spratly Islands between Vietnam and the Philippines. That’s a 0.00009% increase in the country’s total land mass of 2.3 billion acres or roughly three times the size of New York City’s Central Park.

But if China continues on its present course—and the international community doesn’t back down—military confrontation seems likely. Luckily, China must reinforce its military claims to the disputed islands before such a showdown, which gives each side time for negotiation.

China said Monday that it had formally complained to Washington about its “provocative behavior” following the flight of a U.S. Navy surveillance plane over the region last week. The Chinese had warned the a U.S. Navy P-8 surveillance plane eight times to leave Chinese airspace as it flew near Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratlys. The Navy plane refused.

“We urge the U.S. to correct its error, remain rational and stop all irresponsible words and deeds,” foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said Monday. “Freedom of navigation and overflight by no means mean that foreign countries’ warships and military aircraft can ignore the legitimate rights of other countries as well as the safety of aviation and navigation.”

China’s claim of extended sovereignty is upsetting its neighbors, including the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam, as well as Washington. But their denunciations will be little match for the changes coming to the South China Sea sandscape. Unlike U.S. and allied rhetoric about international law, the Chinese are literally making concrete claims in the Spratlys.

“They have manufactured land there at a staggering pace just in the last months,” U.S. Navy Admiral Harry Harris, who becomes commander of U.S. Pacific Command on Wednesday, tells Time. “They’re still going,” he adds. “They’ve also made massive construction projects on artificial islands for what are clearly, in my point of view, military purposes, including large airstrips and ports.”

So far, beyond words of warning to those getting too close to what China contends is its territory, it has only dredging gear, bulldozers and graders to enforce its claim. So the U.S. is ignoring it. But that, Pentagon officials believe, is all but certain to change. And as it changes, the stakes, and resulting tensions, will grow.

The U.S. Navy is weighing dispatching additional warships to the region to buttress its claim that these are international waters. Washington insists that contested sovereignty claims must be resolved through diplomacy and not dredging.

The Chinese digging is happening atop “submerged features that do not generate territorial claims,” David Shear, the Pentagon’s top Pacific civilian, told a Senate panel May 13. “So, it is difficult to see how Chinese behavior in particular comports with international law.”

Such legal niceties are not deterring Beijing. China is building a long airstrip and has deployed an early-warning radar on the Spratly’s Fiery Cross Reef. That will give the Chinese improved detection of what it claims are intruders into its national airspace.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has pushed China’s claim of sovereignty further out into the South China Sea, where it conflicts with claims of local U.S. allies like the Philippines. The U.S. says it can fly within 12 miles of a nation’s coast, while China says its permission is needed for any flights coming within 200 miles.

The early-warning radar, U.S. officials believe, is only the first step in China’s quest to control one of the world’s most vital waterways. More than $5 trillion in goods passes through the South China Sea every year. It contains rich fishing grounds, and potentially great reserves of oil and other natural resources.

The sea is speckled with more than 30,000 islands, making conflicting territorial claims common. The Spratlys consist of some 750 islets and atolls. While spread across 164,000 square miles—the size of California—they total only 1.5 square miles.

The Chinese are likely to bolster their early-warning radar on Fiery Cross Reef with air-defense radars, U.S. Navy officials believe. Once early-warning radars detect incoming aircraft, they will hand off that information to the air-defense radars, which would allow the Chinese to track—and target—any incoming aircraft.

But air-defense radars and the blips they reveal on China’s radar screens are worthless without anything to back them up. So the air-defense radars, U.S. officials believe, ultimately will be tied into a network of air-defense missiles. They’ll be capable of shooting down any interlopers.

Once an air-defense network is in place, China will probably reinforce its claim to what it views as its growing archipelago by basing fighter aircraft there.

Shear, the Pentagon official, noted that China’s land grab is different than Russia’s now underway in Ukraine. “China is not physically seizing territory possessed by or controlled by another country,” he said. “They’re not evicting people from contested land features. They’re not nationalizing territory.”

But they are building an aircraft carrier some 1,000 miles from the Chinese mainland. No one knows better than the U.S. Navy the value of an airfield in the middle of an ocean.

Sure, it won’t be moveable. But it also won’t be sinkable.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com