The shootout between motorcycle clubs and cops in Waco, Tex. that left nine dead and led to more than 190 arrests may have been caused by competing claims of dominion over the state of Texas. But according to experts on outlaw biker clubs, the melee traces its roots to a larger generational shift in the makeup of the clubs themselves.

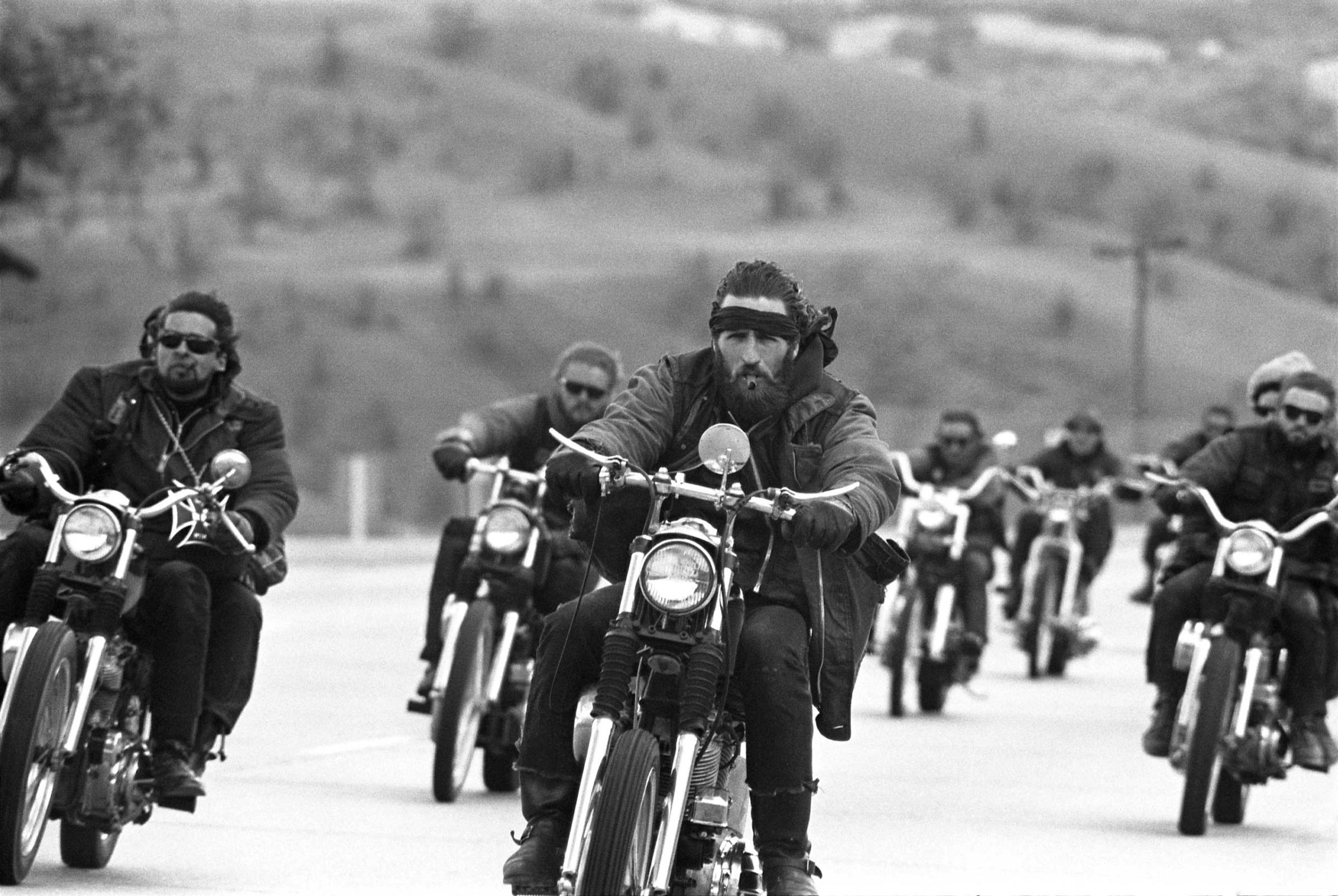

Outlaw motorcycle clubs sprang up in the late 1940s and were especially popular among combat veterans returned from World War II. Membership surged again in the wake of the Vietnam War, and seems to be experiencing another spike from younger veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. While there’s money in the mythos– many clubs have websites and gift shops and attorneys for Hell’s Angels routinely file trademark infringement suits–none of that diminishes the potent appeal that draws members. Besides a love of riding, that lure is often the unit cohesion that’s the bedrock of any military unit, and the extraordinary bonds created by shared risk.

“We’re entering now a third generation in this subculture, and I think that’s as much as anything what’s going on, what happened in Texas,” says Don Charles Davis, who writes the Aging Rebel blog from Los Angeles. Davis says he has no reason to doubt that the Waco shootout broke out, as widely reported, over turf: One club, the Bandidos, has controlled Texas since shortly after the club’s founding in the mid 1960s, mostly by Vietnam Vets, coloring its logo in the red and gold of the Marines Corps, and under the rubric, “We are the people our parents warned us about.” But Davis said he was struck by the relative youth of the Cossacks, the upstart club that also claimed Texas, and rolled into the Waco meeting of motorcycle clubs uninvited and in force.

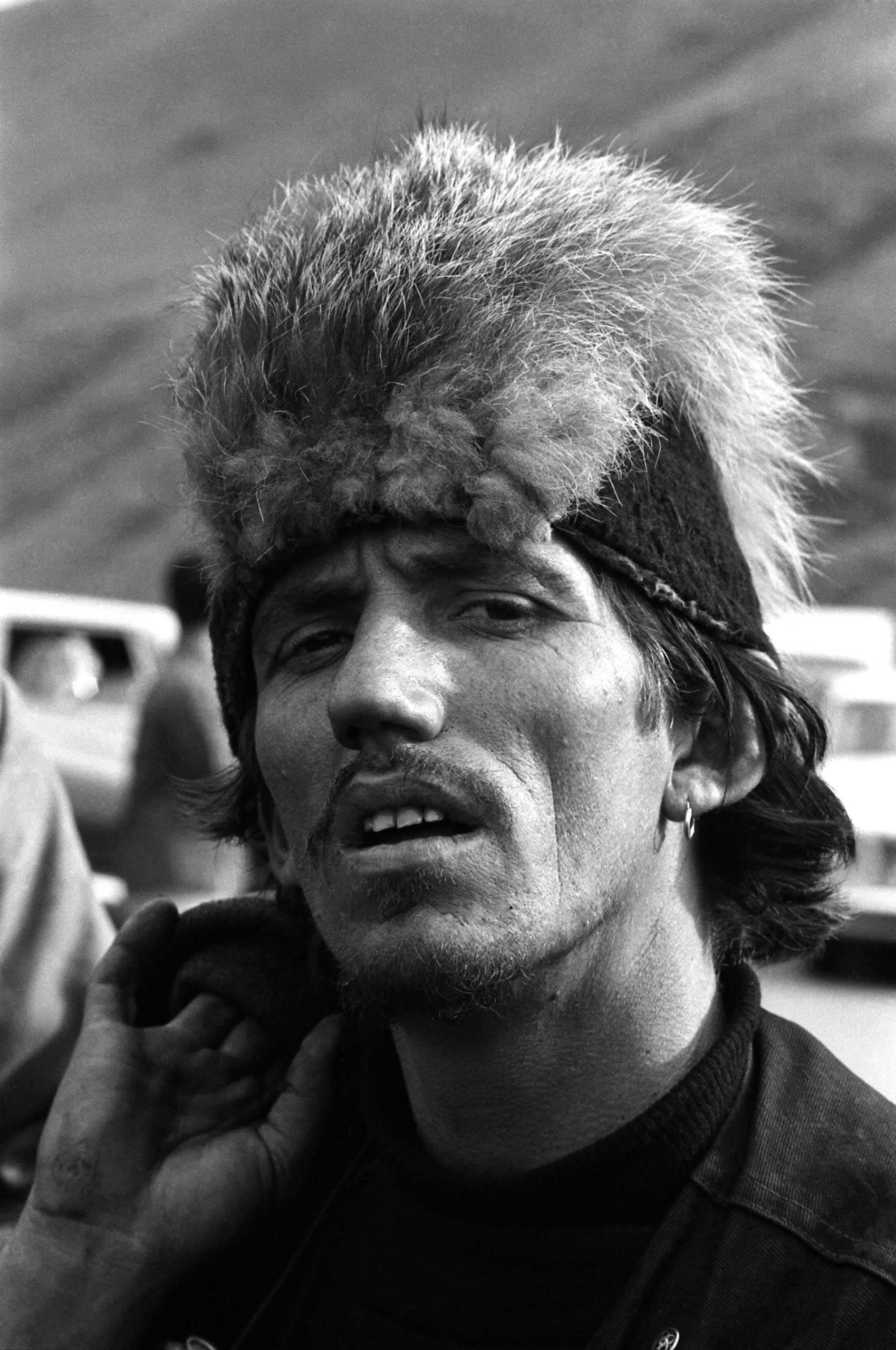

“They’re young. I’m old,” Davis says. “Vietnam vets who were the last big impetus to outlaws, we all have gray hair now. [Hell’s Angels founding member] Sonny Barger is like 76 now. ..A younger club isn’t scared.” He sees the Cassocks rolling on the Bandidos “the same way the Mongols decided to get it on with the Hell’s’ Angels, because they’d been to Vietnam and they weren’t afraid of anything. It’s not only a dispute over territory, but also a matter of generations. We’ve been at war for about 12 years now. There are a lot of disaffected combat vets, and that’s mostly where motorcycle outlaws come from, for various social and psychological reasons.”

Not every expert is fully on board with that theory. Randy McBee, a history professor at Texas Tech and author of the forthcoming “Born to be Wild: The Rise of the American Motorcyclist,” wonders whether anyone who might be dealing with the stress of combat would hang around anything as loud as a Harley engine. Yet the affinity of bikers to military service is on full display each Memorial Day weekend, when thousands assemble in Washington D.C. for the gathering called Rolling Thunder.

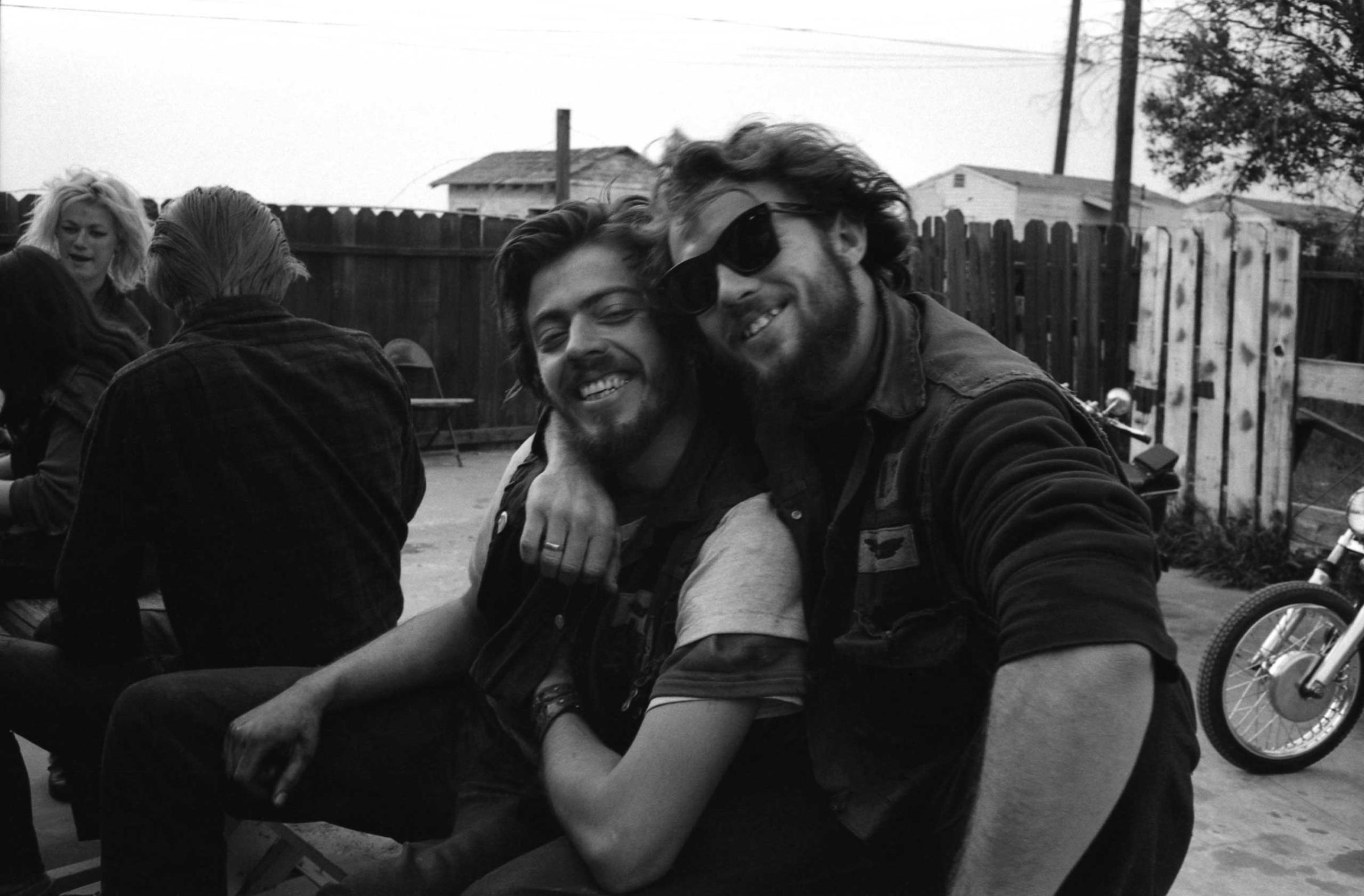

“The argument the Easy Riders were making in the ’80s is, the brotherhood that surrounds service, that surrounds conflict, that there’s no equal to that,” McBee says. “And the closet thing you can get to it is riding.”

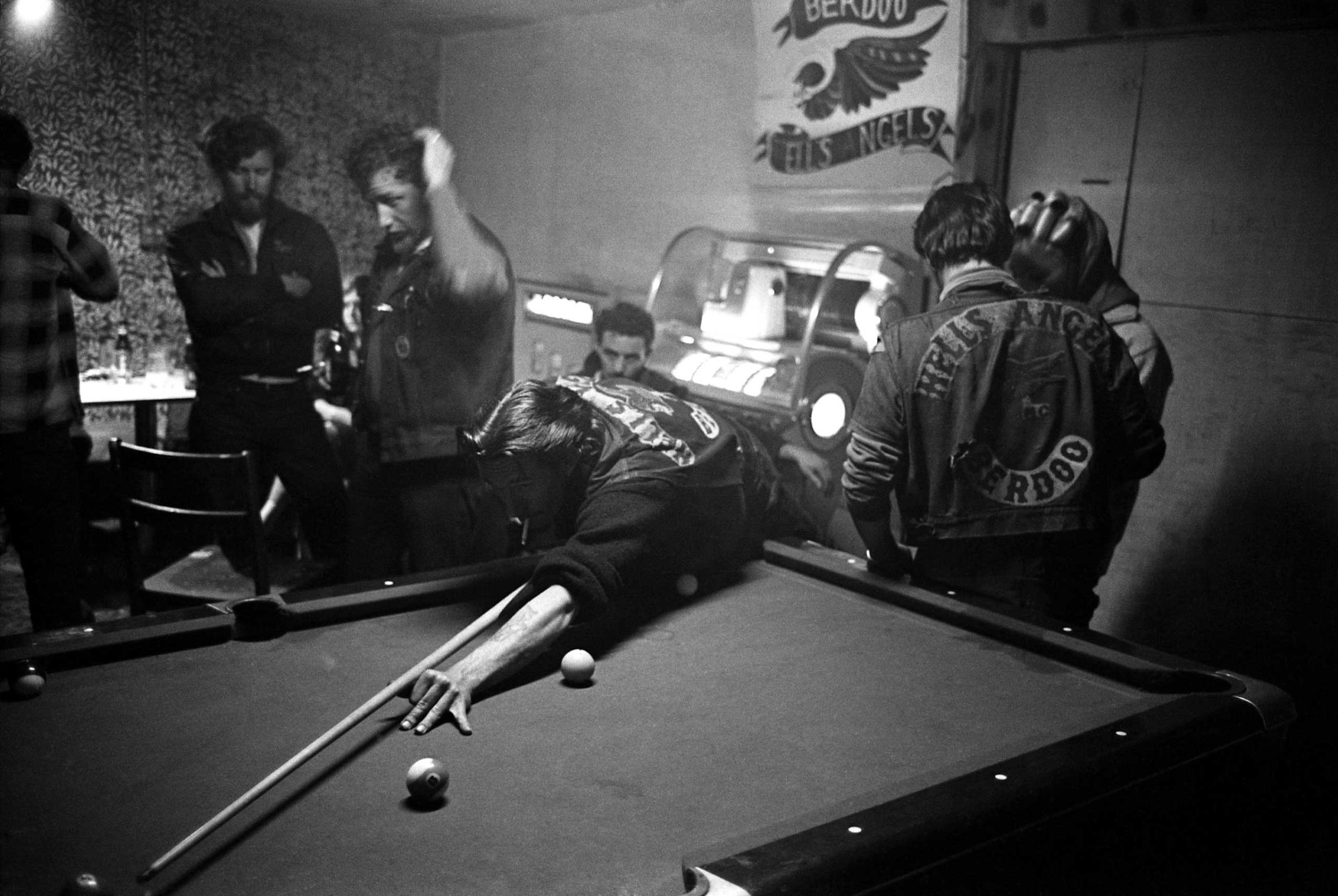

Still, McBee sees a difference between the older clubs–McBee calls the ’60s and ’70s “kind of the golden age of motorcycling”–and the upstarts. “It seems like there’s a boldness to it that’s hard to make sense of,” he says. “Most of the crimes that I’m familiar with from the ’60 and ’70s, were in [private] clubs, or bars, not in a restaurant in Waco, Texas.”

“Motorcycle clubs are function of military service, period,” declares William Dulaney, who is both national president of Hell on Wheels Motorcycle Club and a professor of organizational communication at Air University, located on Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama. “Chain of command is very strictly adhered to. Its’ about identity for a group of people who, outside this social structure, don’t have much identity. You’re talking about a core identity to a bunch of warriors.”

And yet, even as Harley sales soared and weekend warriors, known derisively by outlaw clubs as RUBs, or rich urban bikers, crowded highways, the clubs that started it all lost a lot of their juice. “Back in the ’80s, or like 1995, dude, gangland, no doubt about it,” Dulaney says. “But those days are gone. ” Federal RICO prosecutions and other law enforcement efforts have dramatically reduced the criminal threat level from outlaw groups, as perhaps has aging. Dulaney now numbers himself among the older generation, and understands the violence in Waco as a problem of kids these days.

“They don’t have years and years if not decades in the subculture, understanding that there is hierarchy,” he says. Young bucks may enjoy the swagger of wearing a leather vest, but they fail to respect the full import of the patches, or “colors,” sewn on the back, he says. The diamond-shaped patch reading “1%” denotes the wearer as a member of the outlaw elite. And the place name — “Texas” — sewn at the base of the vest in the embroidered crescent bikers call the bottom rocker, announces more than a claim on turf.

“The way to understand the bottom rocker, with 1 percenters, is it’s territory, yeah, but it’s responsibility,” Dulaney says. “Because they have responsibility to enforce peaceful coexistence in that area. Because if they don’t, law enforcement will come in and be all over you.”

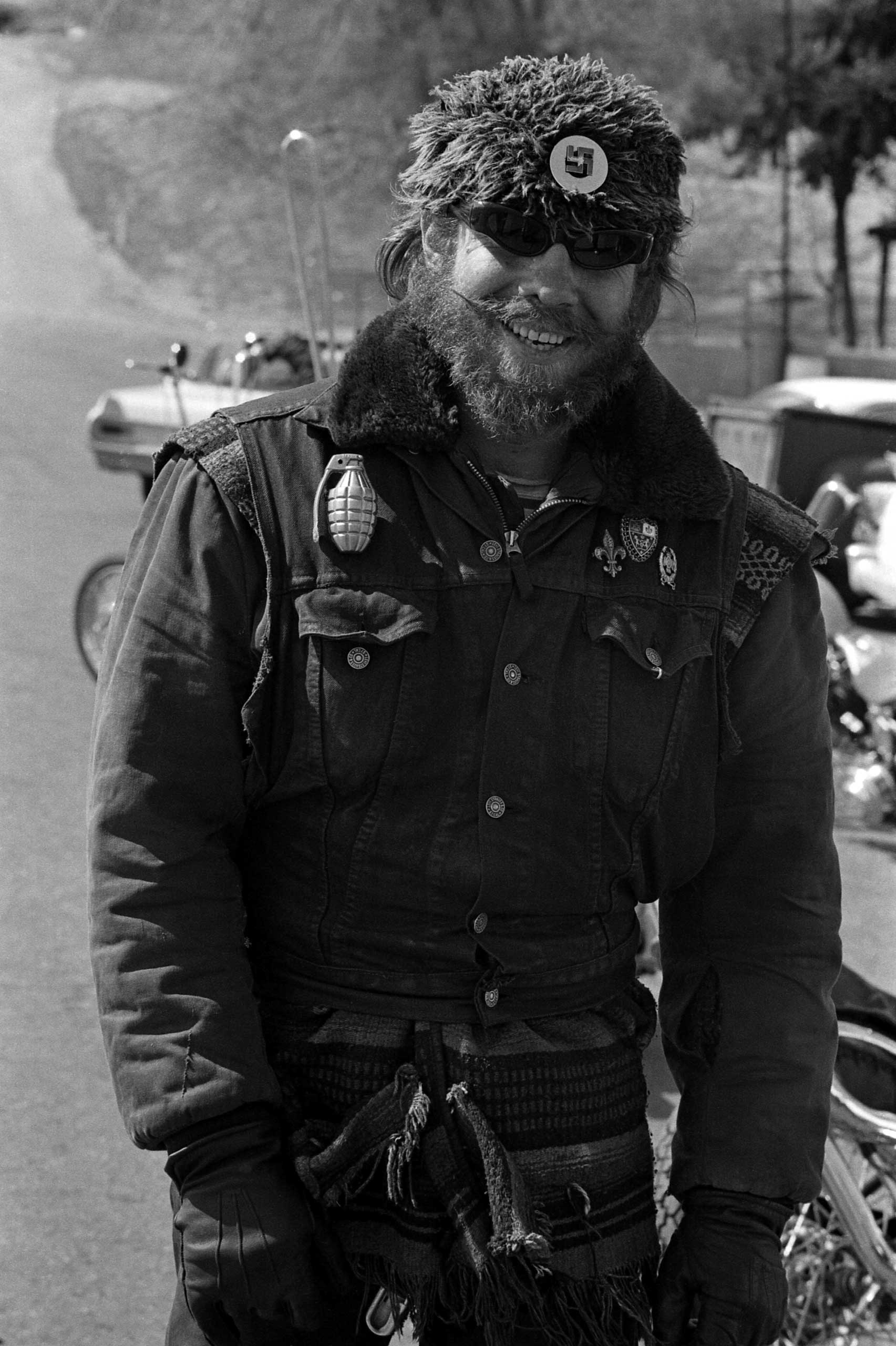

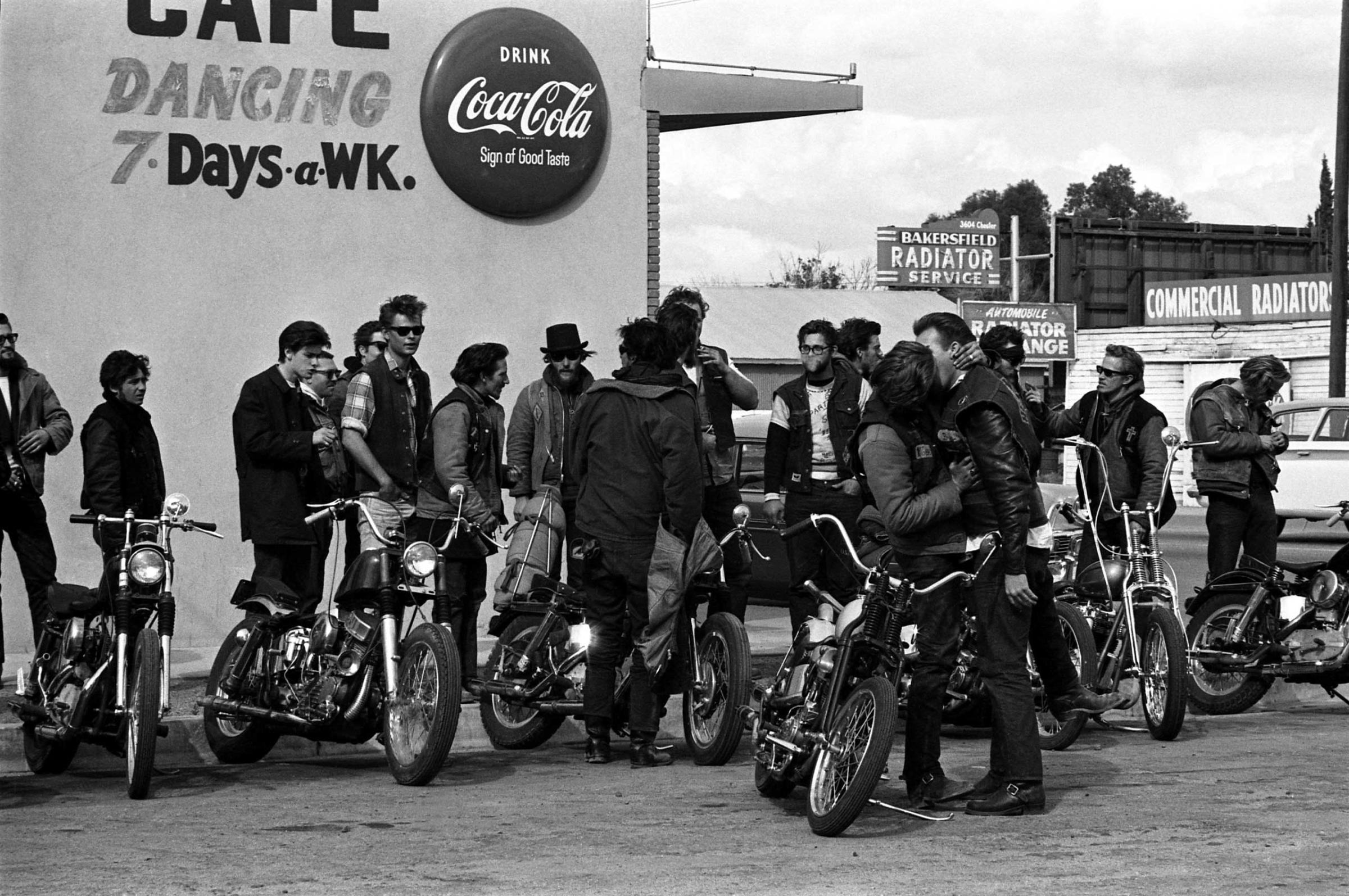

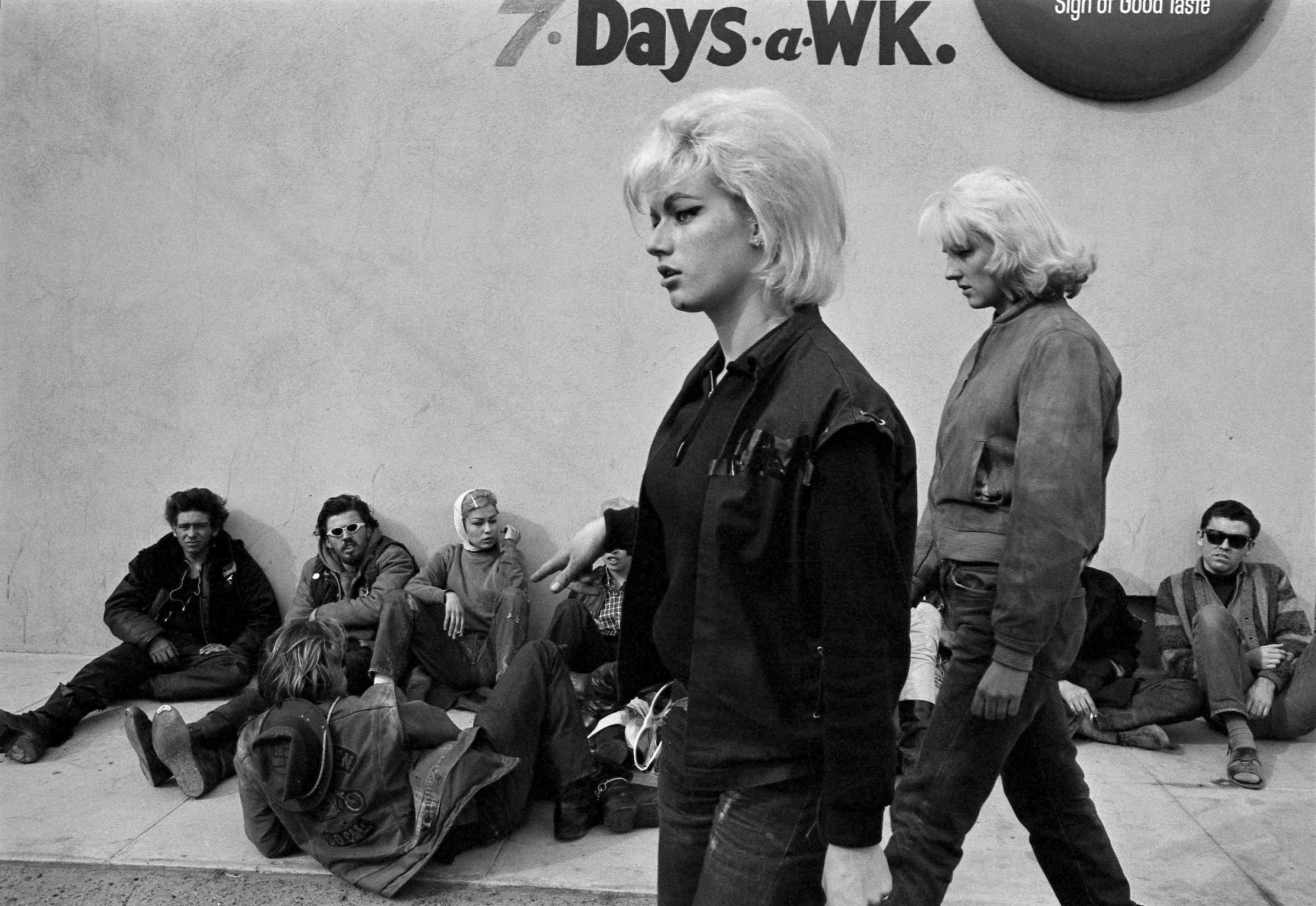

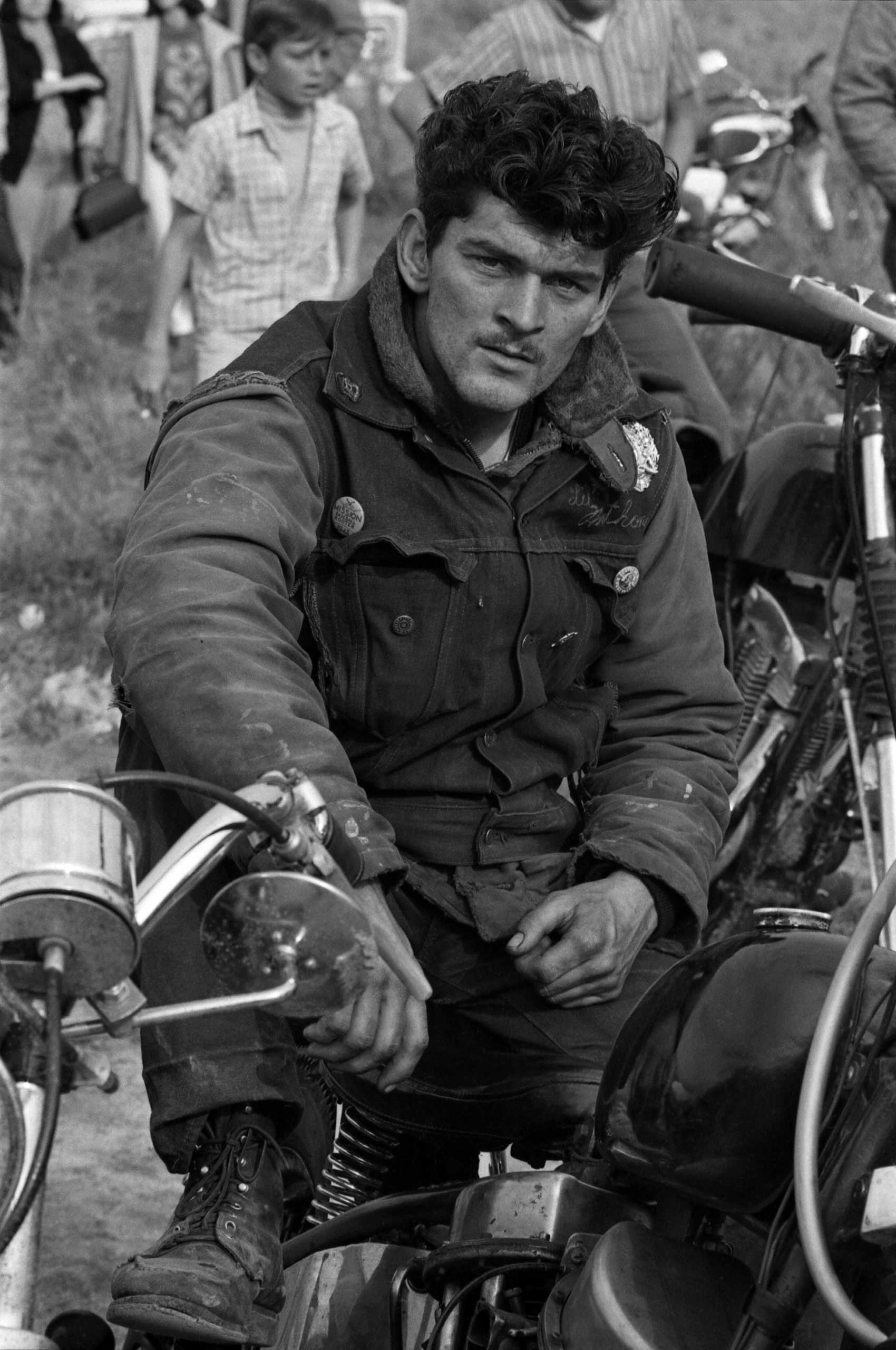

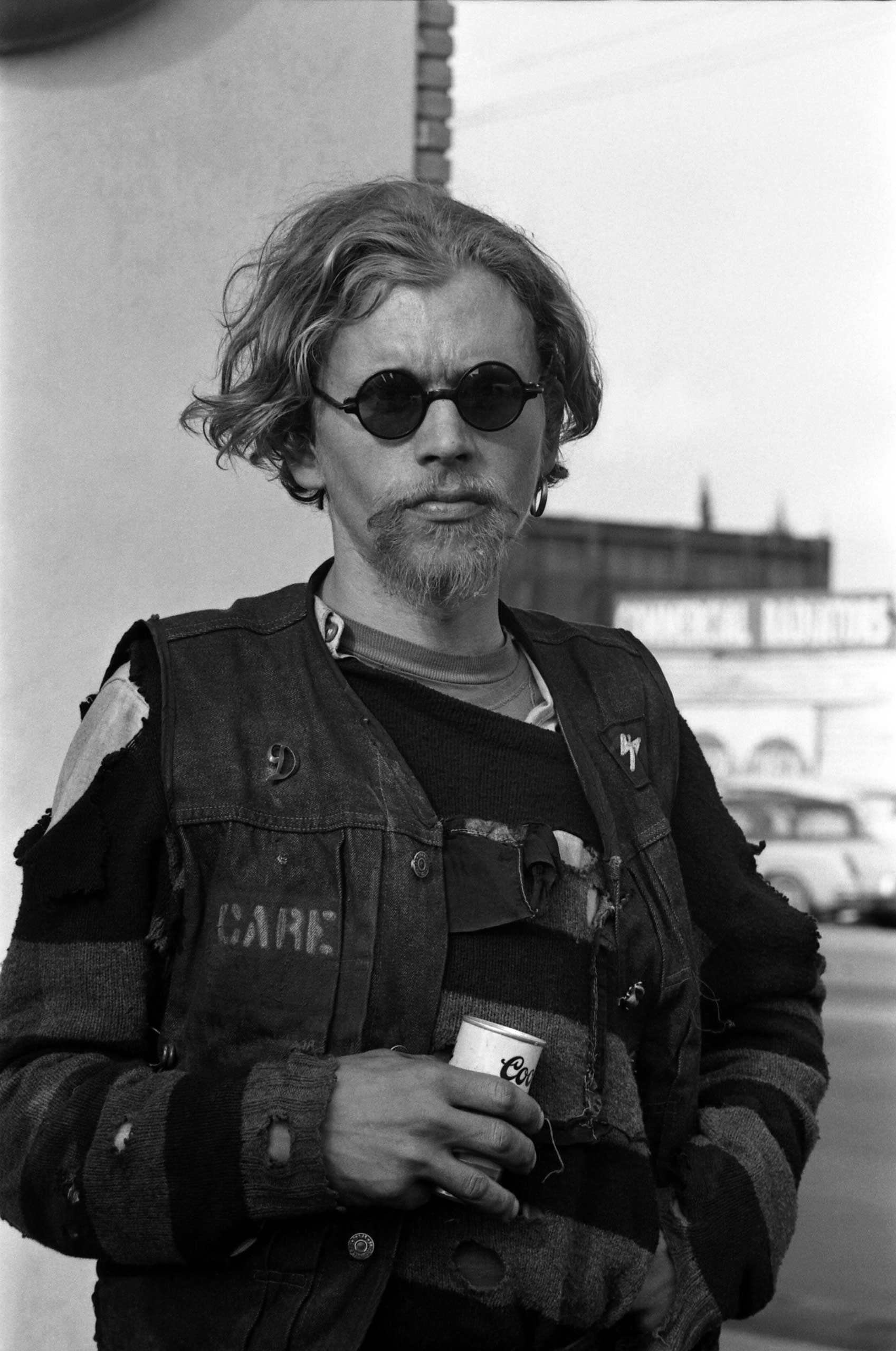

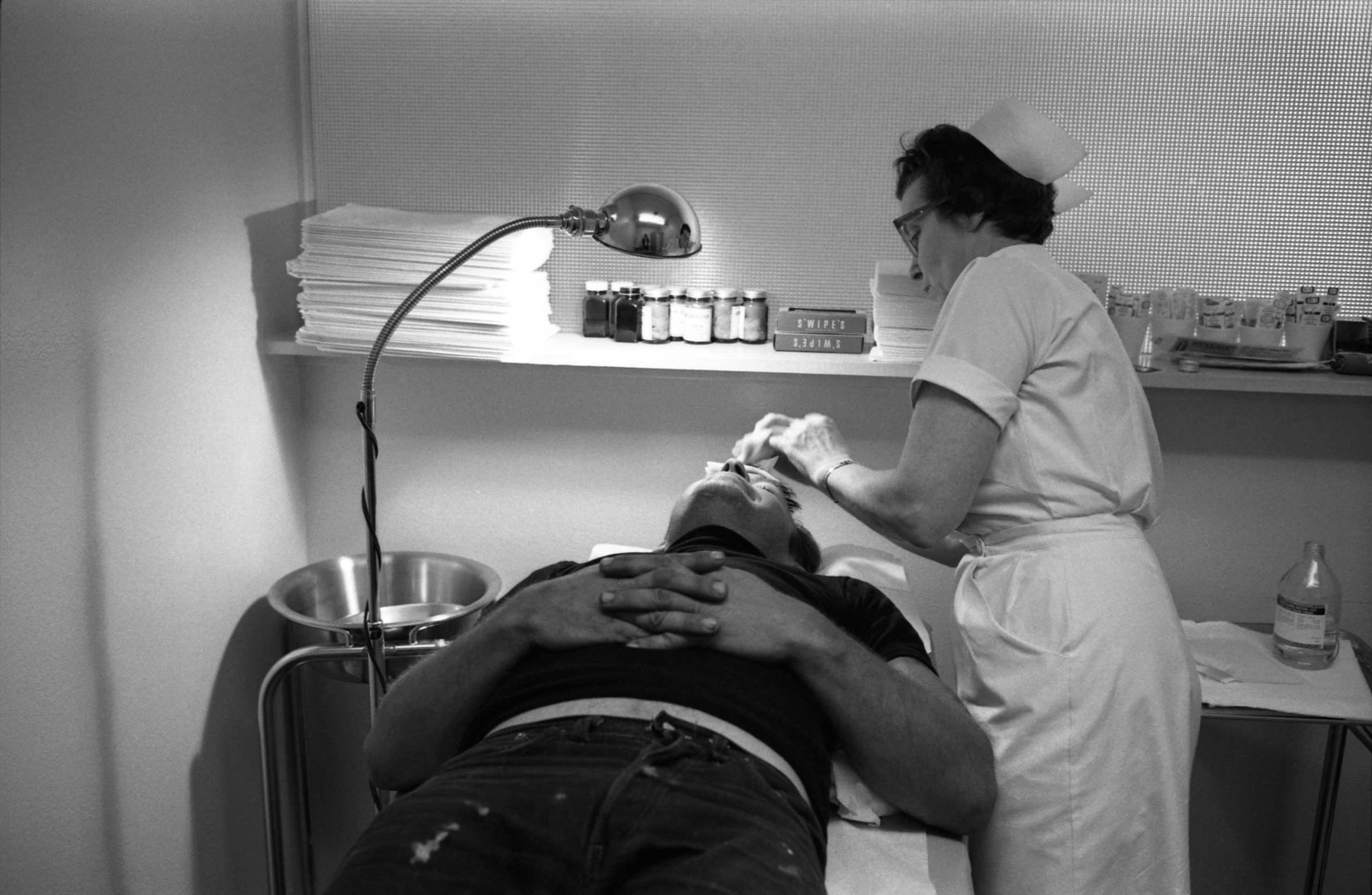

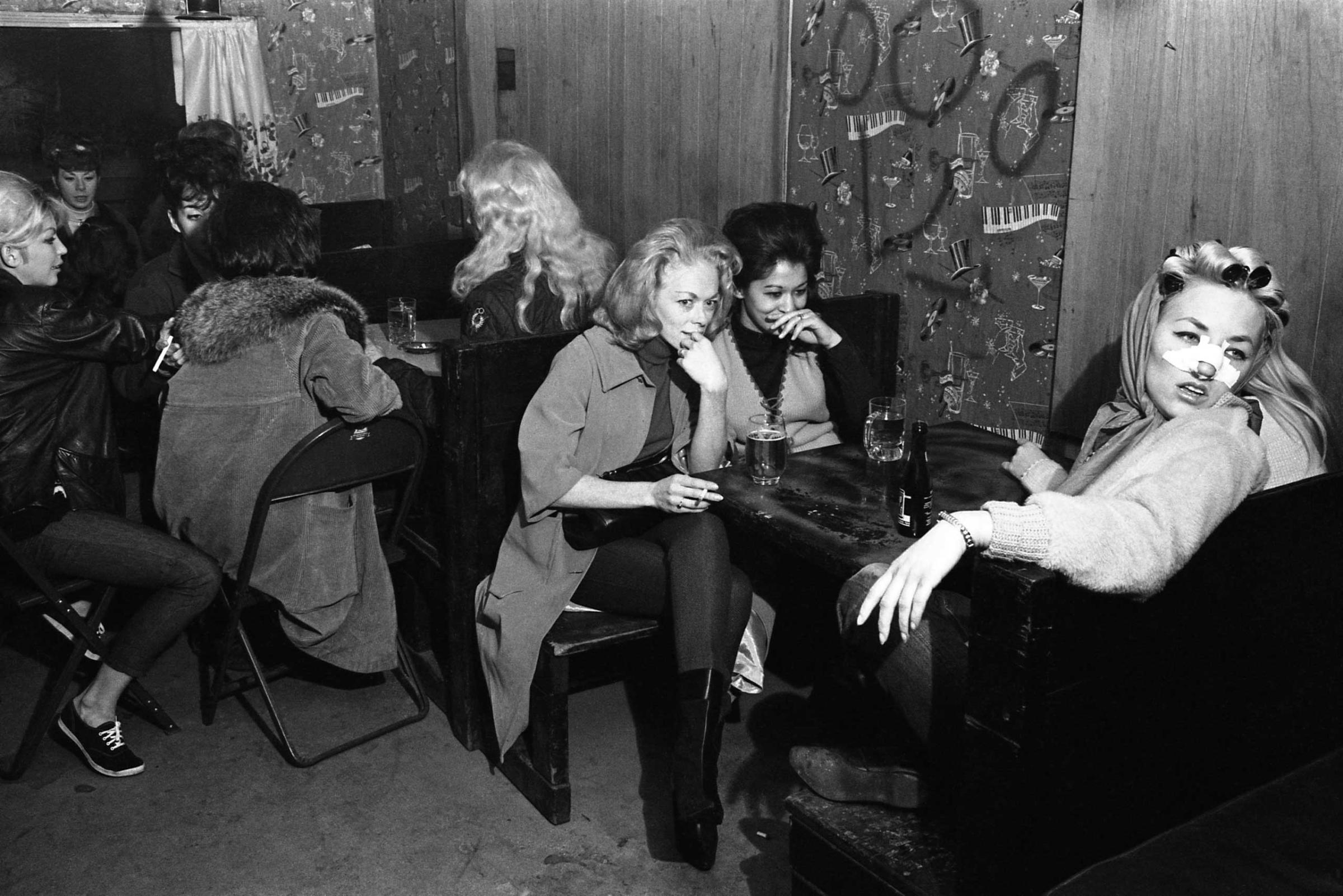

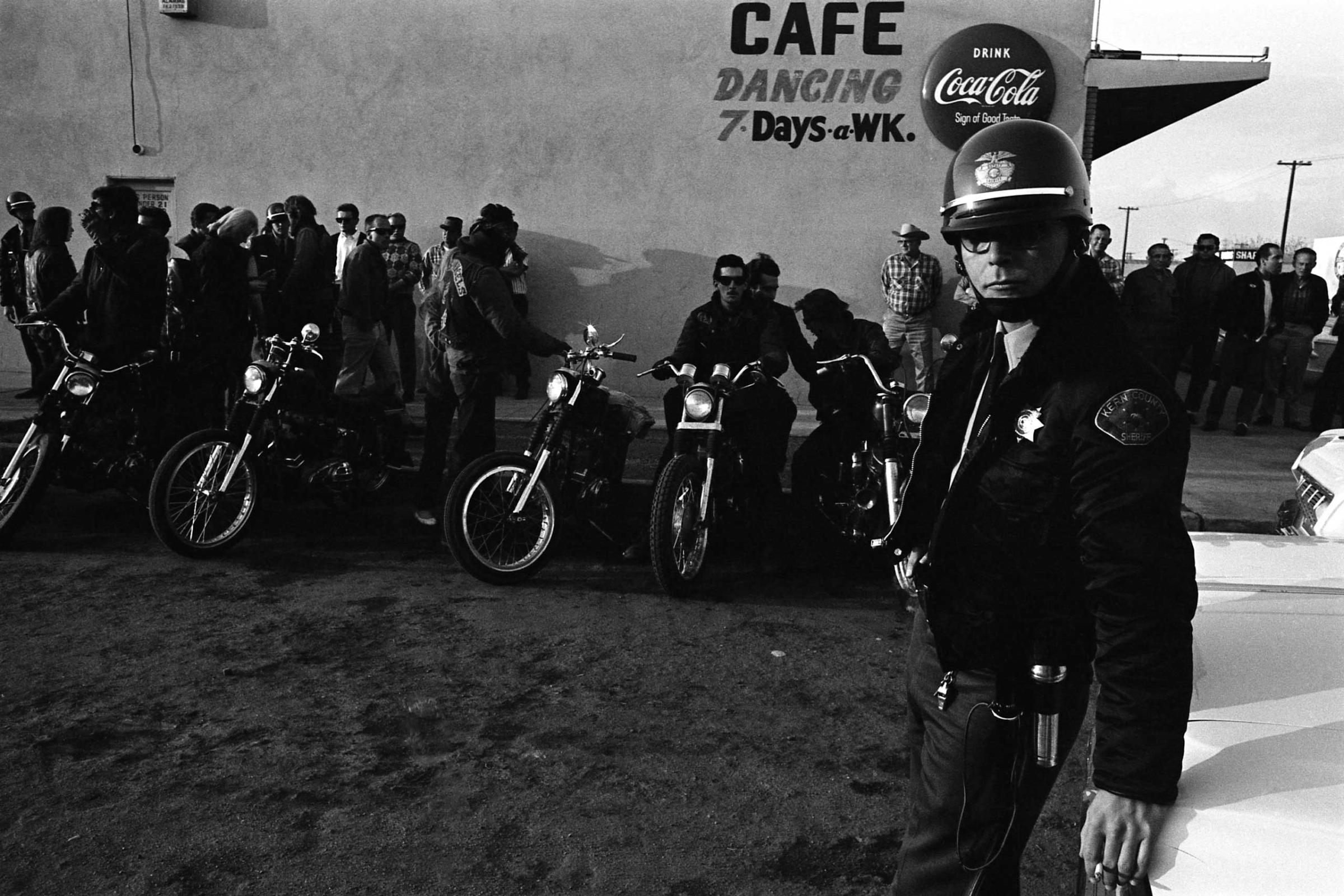

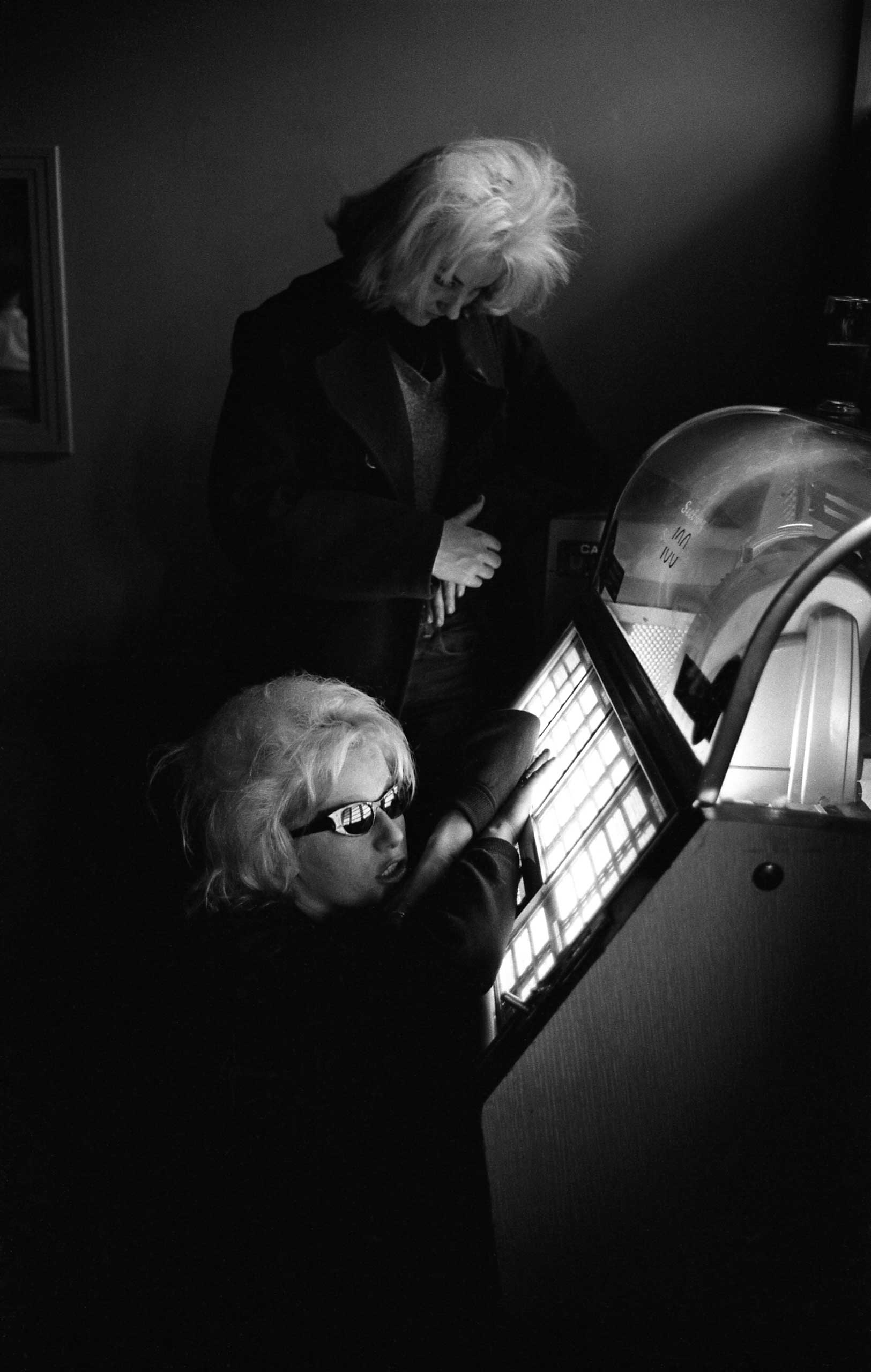

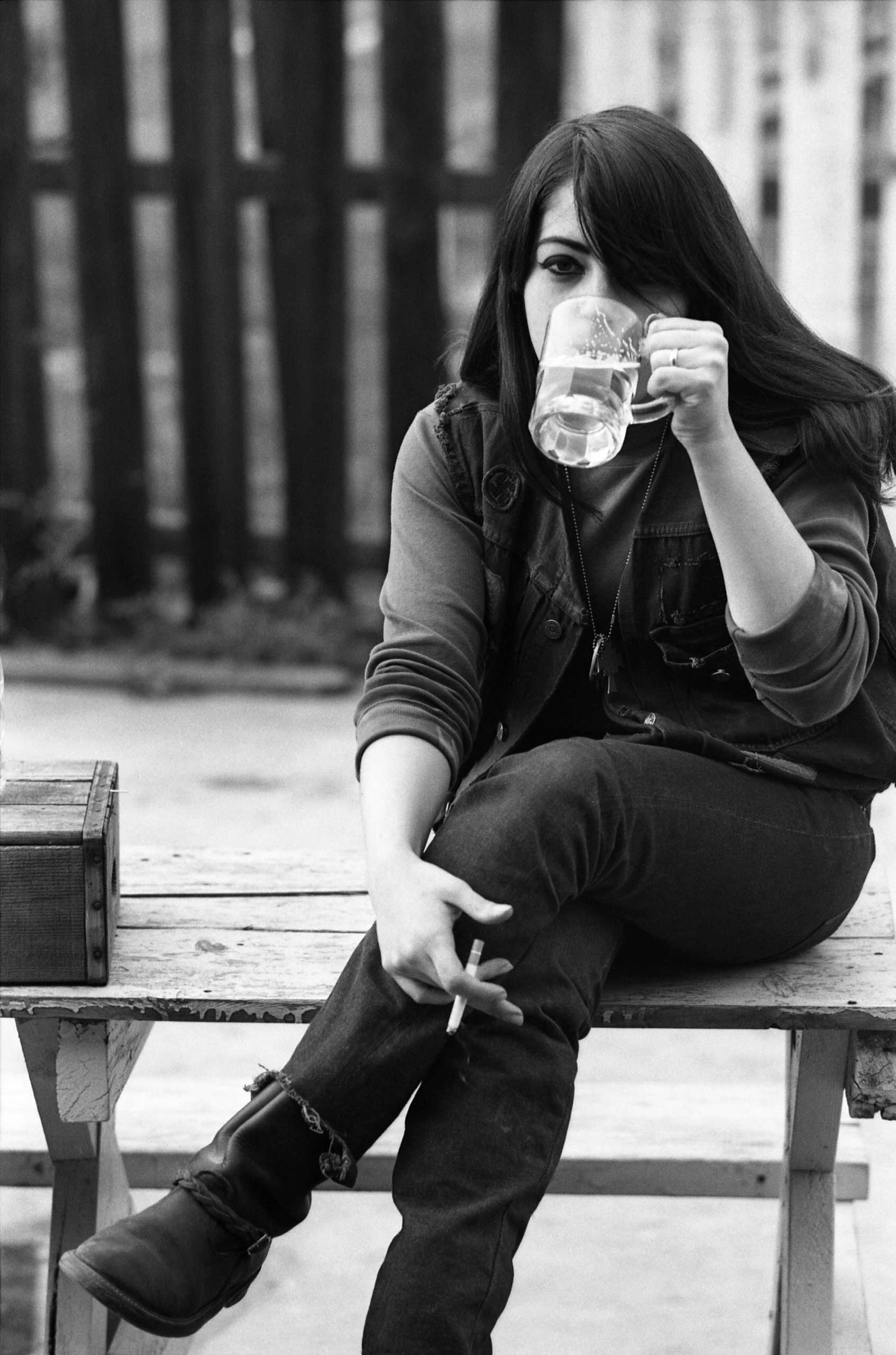

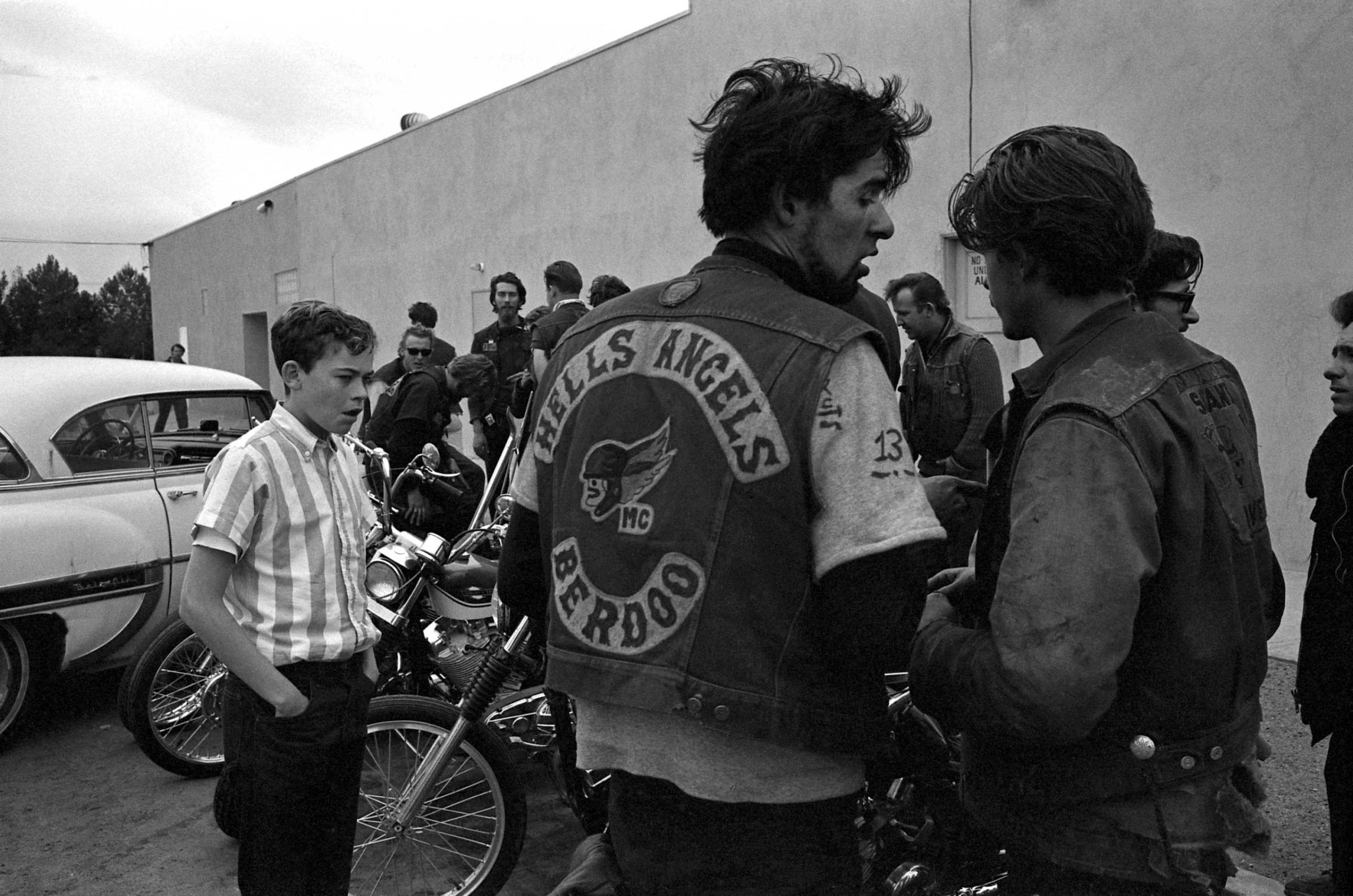

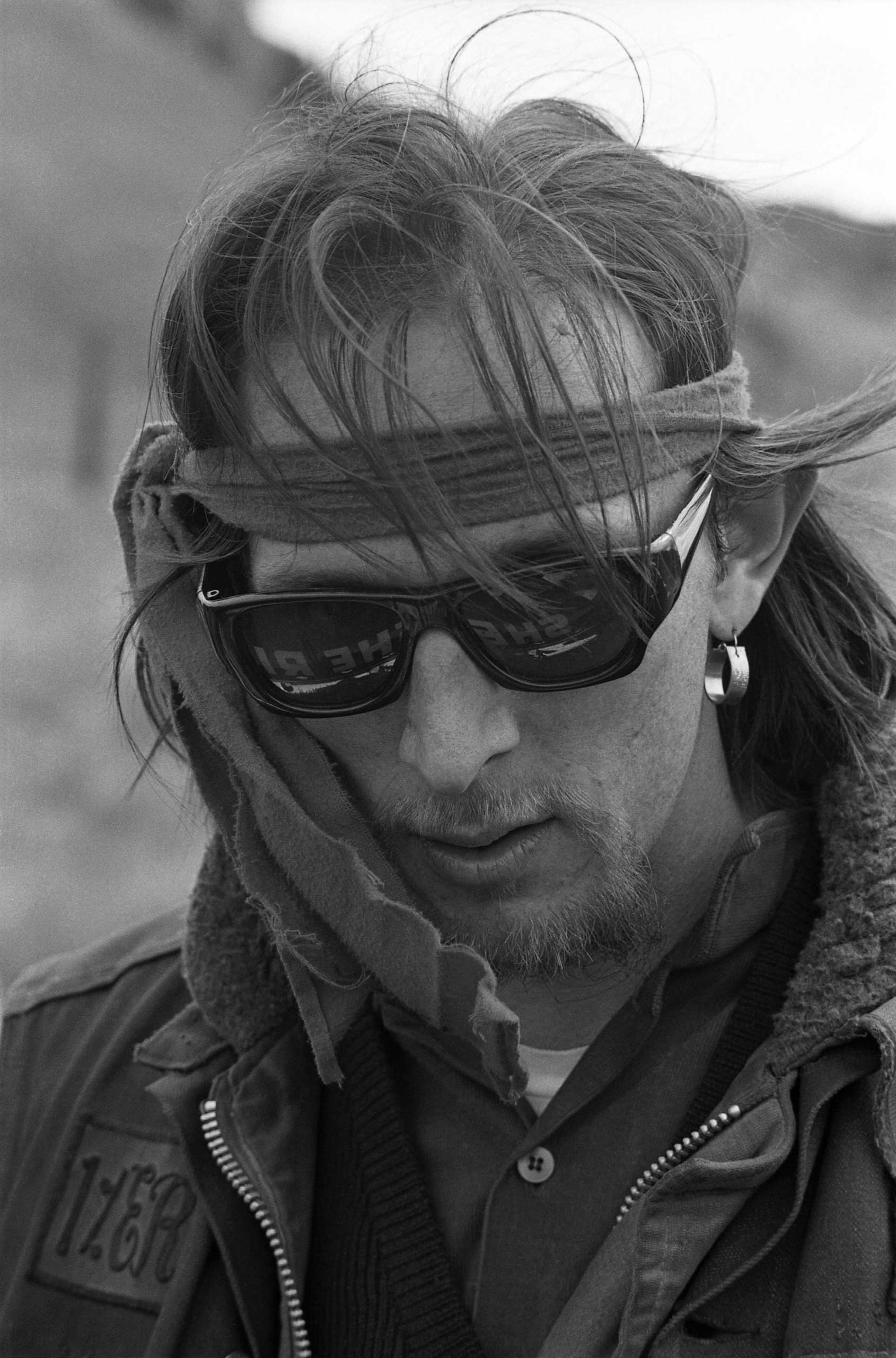

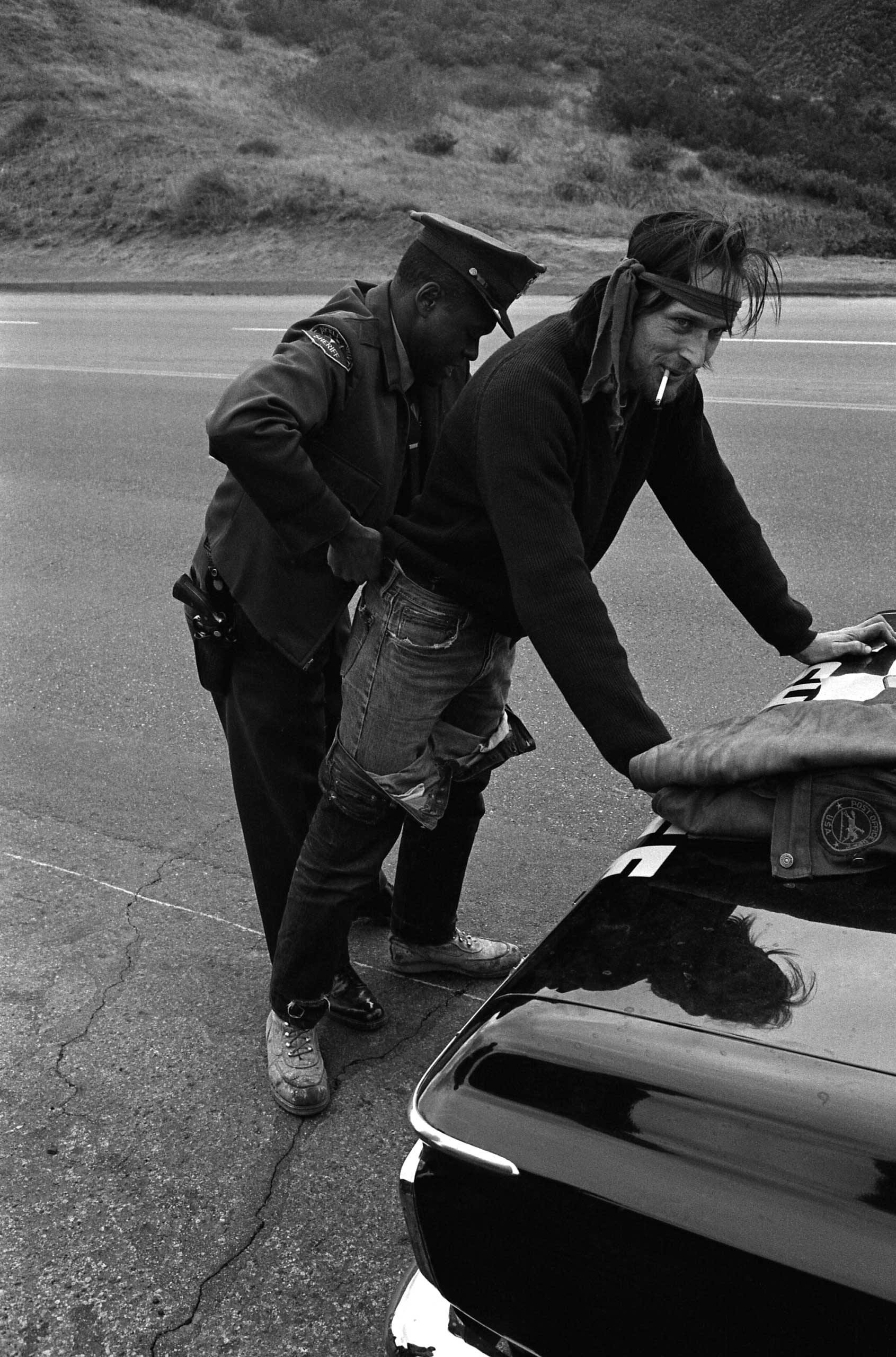

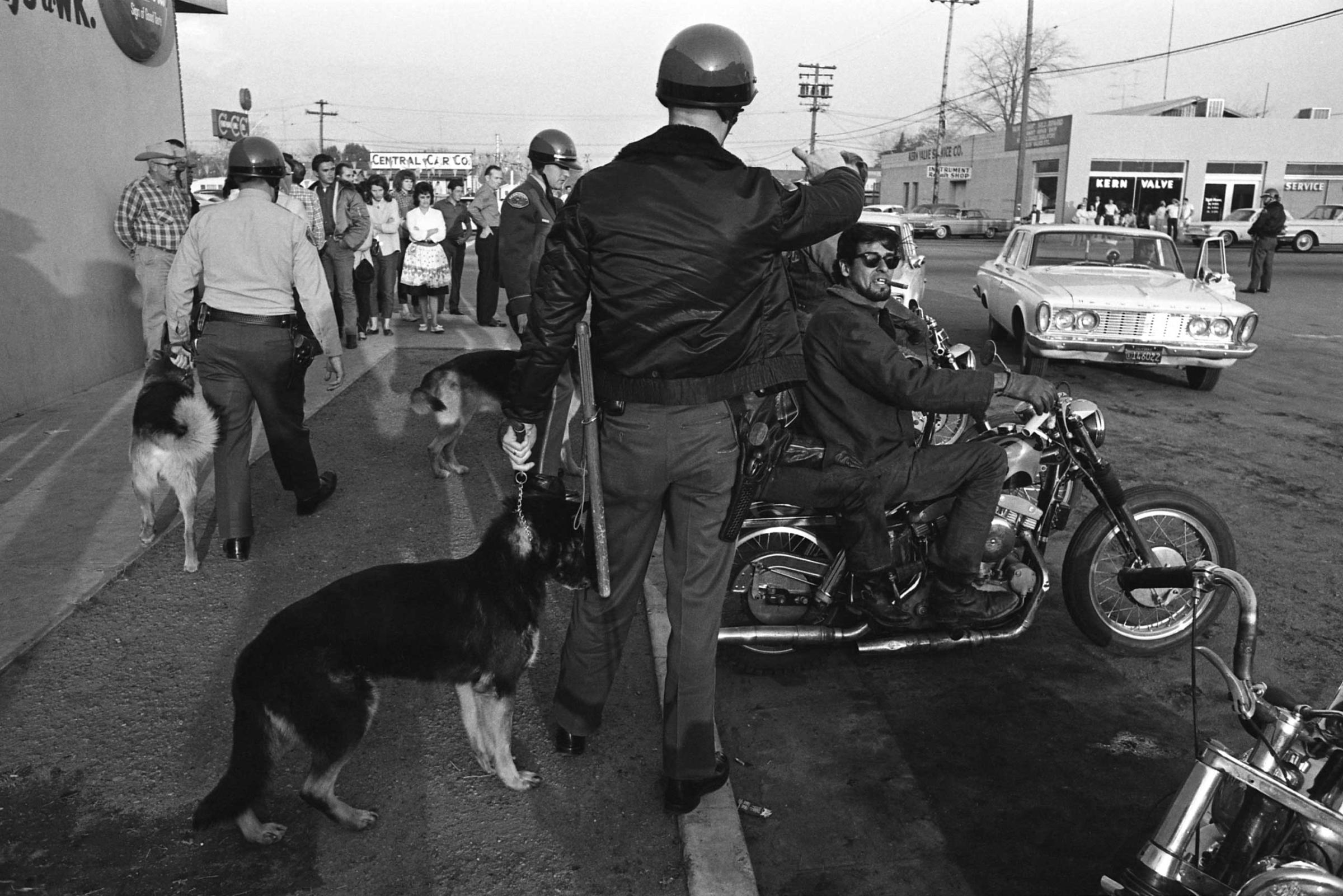

LIFE Rides With Hells Angels, 1965

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com