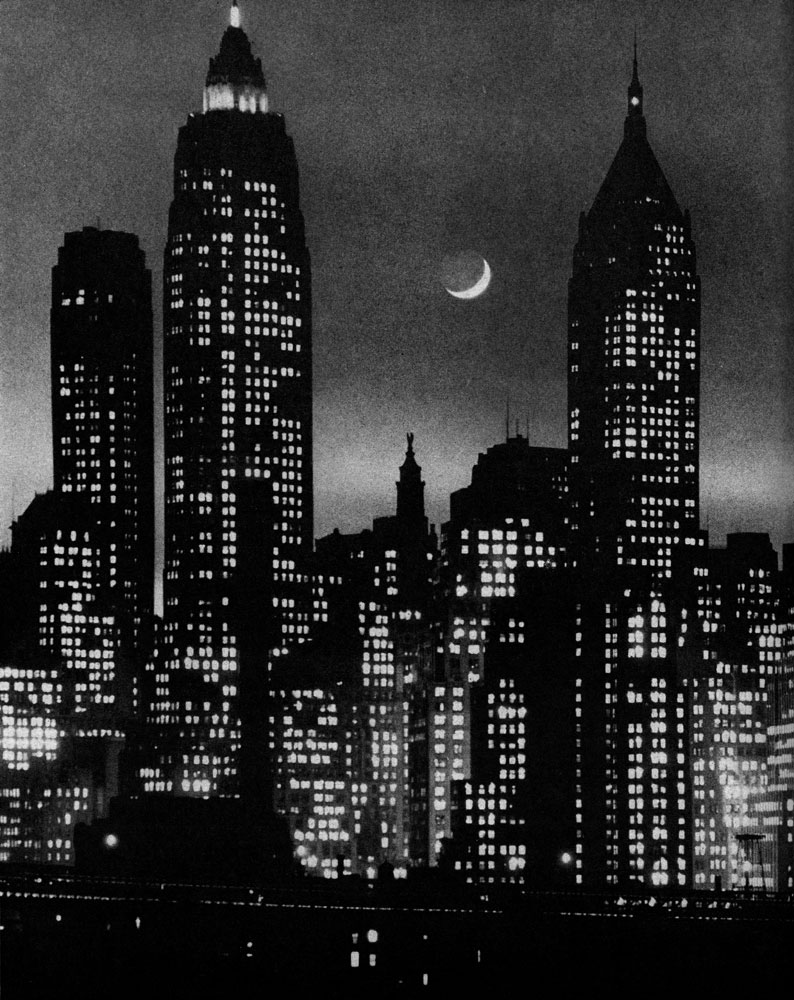

If one had to choose a single photographer whose work would serve as a visual biography of New York City in its postwar Golden Age—when Gotham became, in a sense, the capital of the world—the name Andreas Feininger would have to be in the mix. Paris-born, raised in Germany and, for a time, a cabinet-maker and architect trained in the Bauhaus, Feininger’s pictures of New York in the 1940s and ’50s helped define, for all time, not merely how a great 20th century city looked, but how it imagined itself and its place in the world. With its traffic-jammed streets, gritty waterfronts, iconic bridges and inimitable skyline, the city assumed the character of a vast, vibrant landscape.

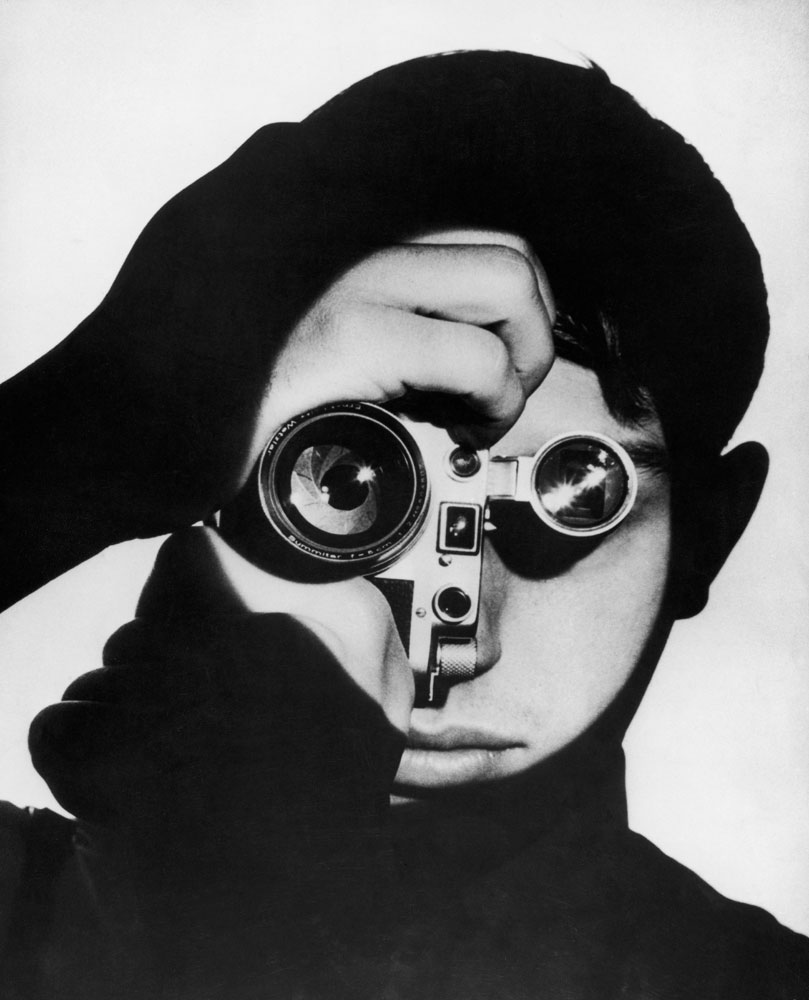

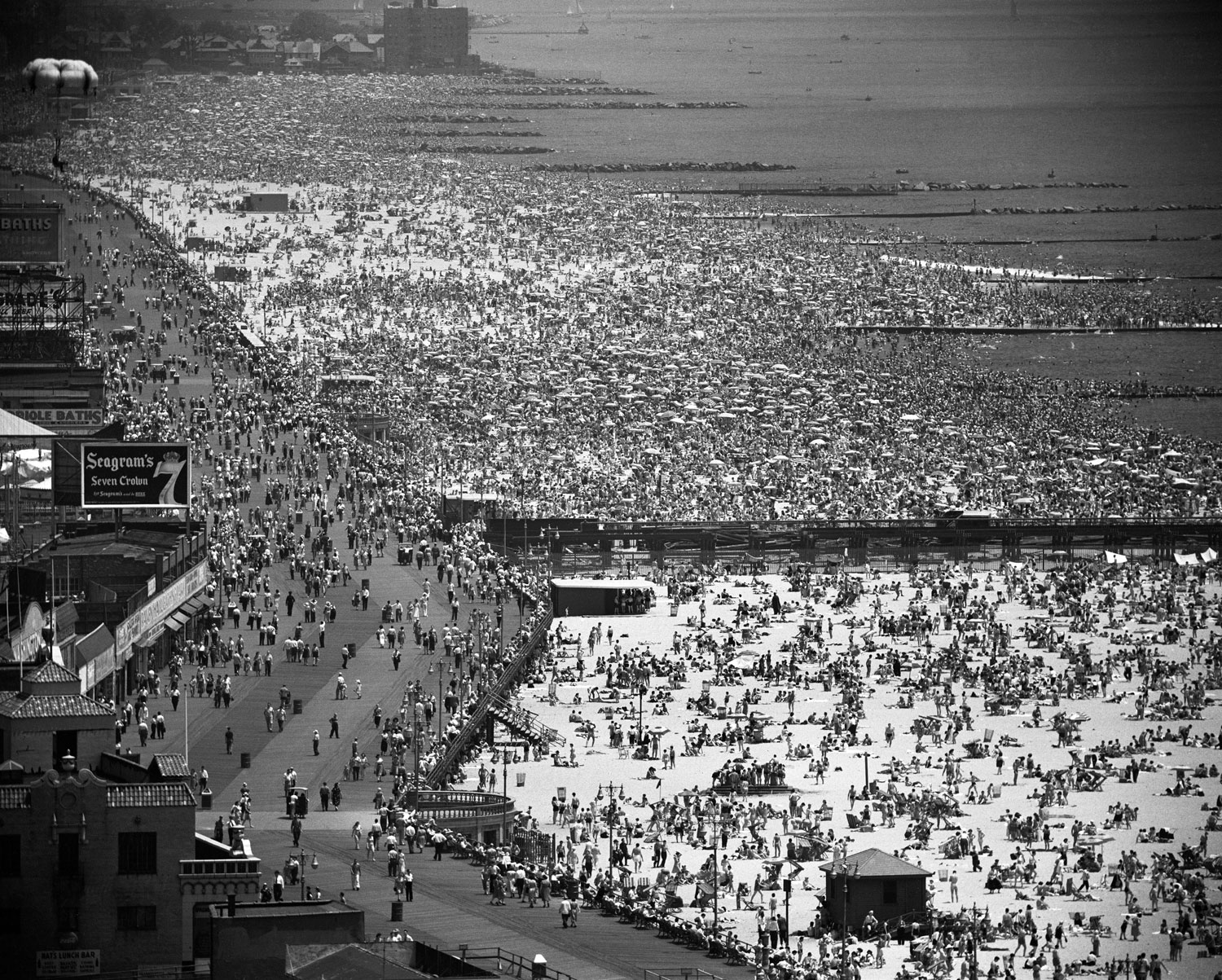

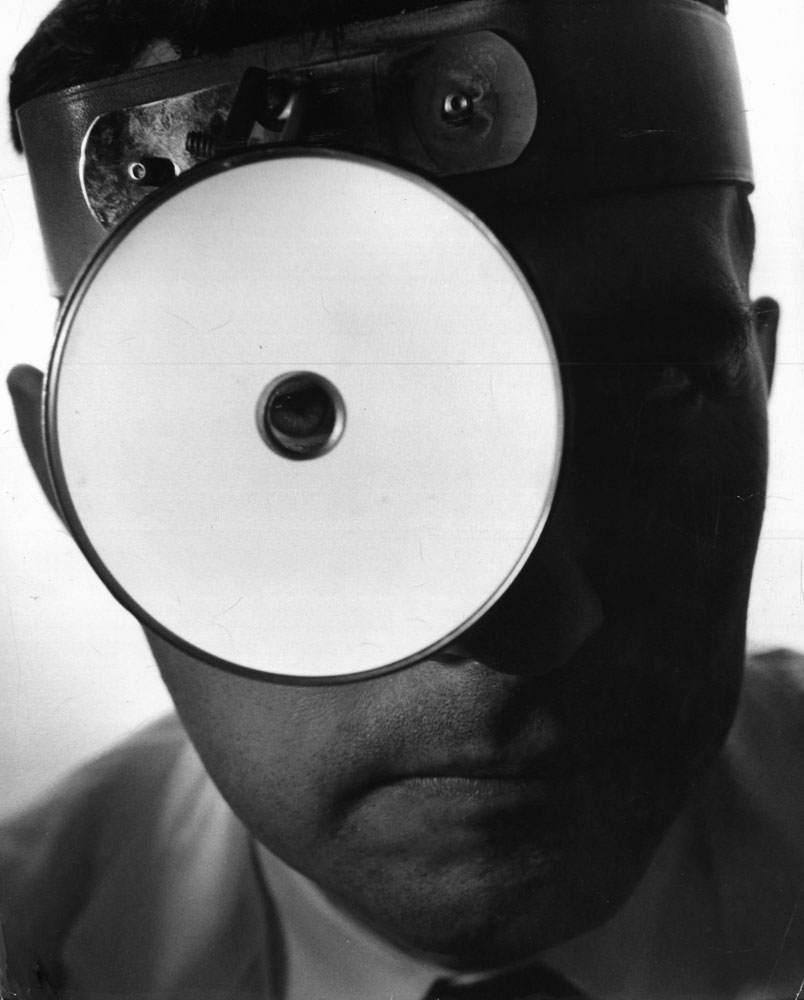

New Yorkers, meanwhile—that landscape’s inhabitants—were often an afterthought: it was form, pattern and, perhaps above all else, scale that Feininger sought. Human beings might have built this thrilling, sprawling, purposeful urban panorama, but their presence in Feininger’s pictures was not necessary; their handiwork would suffice. (In fact, in his single most famous portrait of a person, his 1955 photo of the young photographer Dennis Stock, Feininger obscures—or, more accurately, replaces—the human face with the clean, mechanistic contours of a camera.)

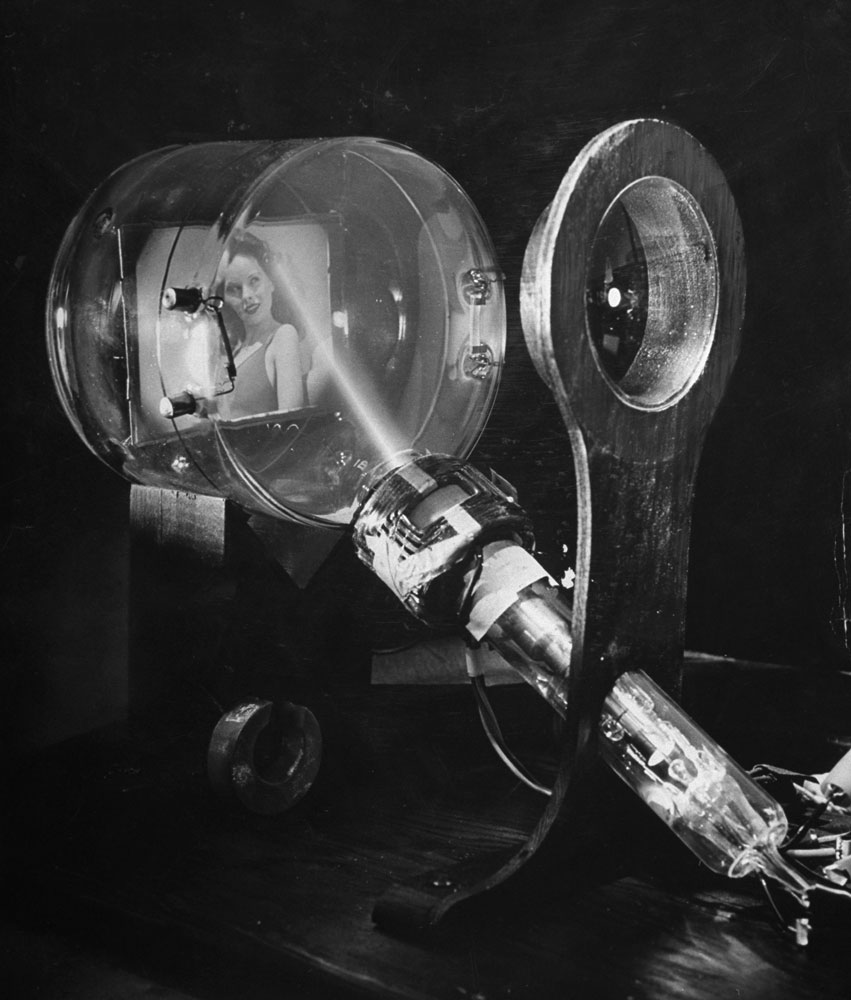

Of course, no one who worked on staff for LIFE—as Feininger did for almost two decades, from 1943 until 1962—could be defined by a single theme, or by a simplistic approach to any and all assignments. Yes, most of LIFE’s photographers were especially passionate about or adept at photographing specific subjects: Fritz Goro excelled at finding creative ways to capture the advances and perils of science and technology; Nina Leen was terrific at shooting fashion and animals; George Silk made countless classic sports photographs, Allan Grant was at home among the strange and exotic denizens of Hollywood. But none of them would have dreamed of—or would have been allowed to—indulge their singular passion to the exclusion of all other topics.

Feininger was no different. While his work often managed to incorporate his Bauhaus-influenced interest in—one might almost say reverence for—simplicity in all things, as well as his respect for neatness and disdain for decoration in architecture and in art, he was hardly limited to making shot after shot of the Manhattan skyline or the Brooklyn Bridge or some other element of that familiar urban vista. He had proven himself a master metropolitan portraitist, and profitably turned his attention to other realms in more than 340 assignments for LIFE through the years.

Fascinated from the time he was a young boy in Germany by the natural world, Feininger made beautiful pictures of the skeletons and bones of animals, snakes and birds, investing them with an austere power that the creatures perhaps lacked when alive and covered with flesh, fur, feathers or scales. His 1956 picture of Niagara Falls in winter (slide #17), with two small human forms silhouetted against a scene, might have been lifted from the last Ice Age, while one of his most famous and most frequently reproduced photographs—Route 66 in 1947 Arizona (slide #7)—somehow manages to reference, in a single frame, the allure of the open road, the confluence of the man-made and natural worlds and the myth of the inexhaustible American West.

The author of more than 30 books—including at least one acknowledged classic, the autobiography Andreas Feininger: Photographer (1966)—Feininger’s photographs were shown in solo and group shows in places as diverse as the Museum of Natural History, the International Center of Photography, MoMa, the Metropolitan, the Smithsonian and in smaller galleries and exhibitions around the world. A retrospective of his six-decade career, featuring 80 of his own favorite black-and-white pictures from 1928 through 1988, toured Europe in the late 1990s.

Andreas Feininger died in Manhattan in February 1999. He was 92.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com