Sometime in 2007, my aunt called my mom to tell her about a new show on AMC about an advertising man in the mid-20th century, with a house and family in Westchester County, New York, who makes a habit of taking liquid lunches with his colleagues. “You have to watch it,” she said. “It’s our childhood.”

My grandfather, James Wickersham, was not known for philandering or a bleak outlook on life, à la Mad Men‘s Don Draper. But otherwise, the similarities felt uncanny: He worked for McCann-Erickson, the firm that acquires Sterling Cooper & Partners in season seven, from 1956 to 1967, a hearty overlay of the years the show takes place. Like Don, his career began in the military, but he was a bit older, fighting in WWII rather than Korea. At McCann, he was sort of a fusion Don and Roger—he worked on the account side, not creative, but he often made the pitch to the client. At the same time, his work required him to wine and dine clients at restaurants like Lutèce. Like all of the Mad Men, he had a fully stocked bar in his office.

Grandpa joined McCann-Erickson with the title “account executive” and left as “chairman and chief operating officer of McCann/ITSM.” A few of his roles over the years were for different subsidiaries of McCann’s holding company, Interpublic. He isn’t around anymore to confirm any details, but our family remembers a few anecdotes from his pitching years. McCann wanted Don to work on Coca Cola; my grandfather actually did. He also worked on Standard Oil a.k.a. Esso (now Exxon) when its slogan was “Put a tiger in your tank.” He played a big role in the company’s work for the Barry Goldwater presidential campaign in 1964.

In a pitch to IBM that involved automating its systems, he filled in for a computer operator who got sick before the meeting. He was thoroughly briefed for his job as pinch hitter, but he stumbled on a simple question: “What language does your computer system use?” an IBM exec asked. “English?” he said with a smile. Everyone in the room apparently cracked up.

He had a lot of respect for the creative side, but could be dubious of ads he considered ineffective. My uncle recalls that while watching television with him growing up, my grandfather would say after clever-seeming ads ended, “Quick, tell me what the product was!” Often, he couldn’t remember.

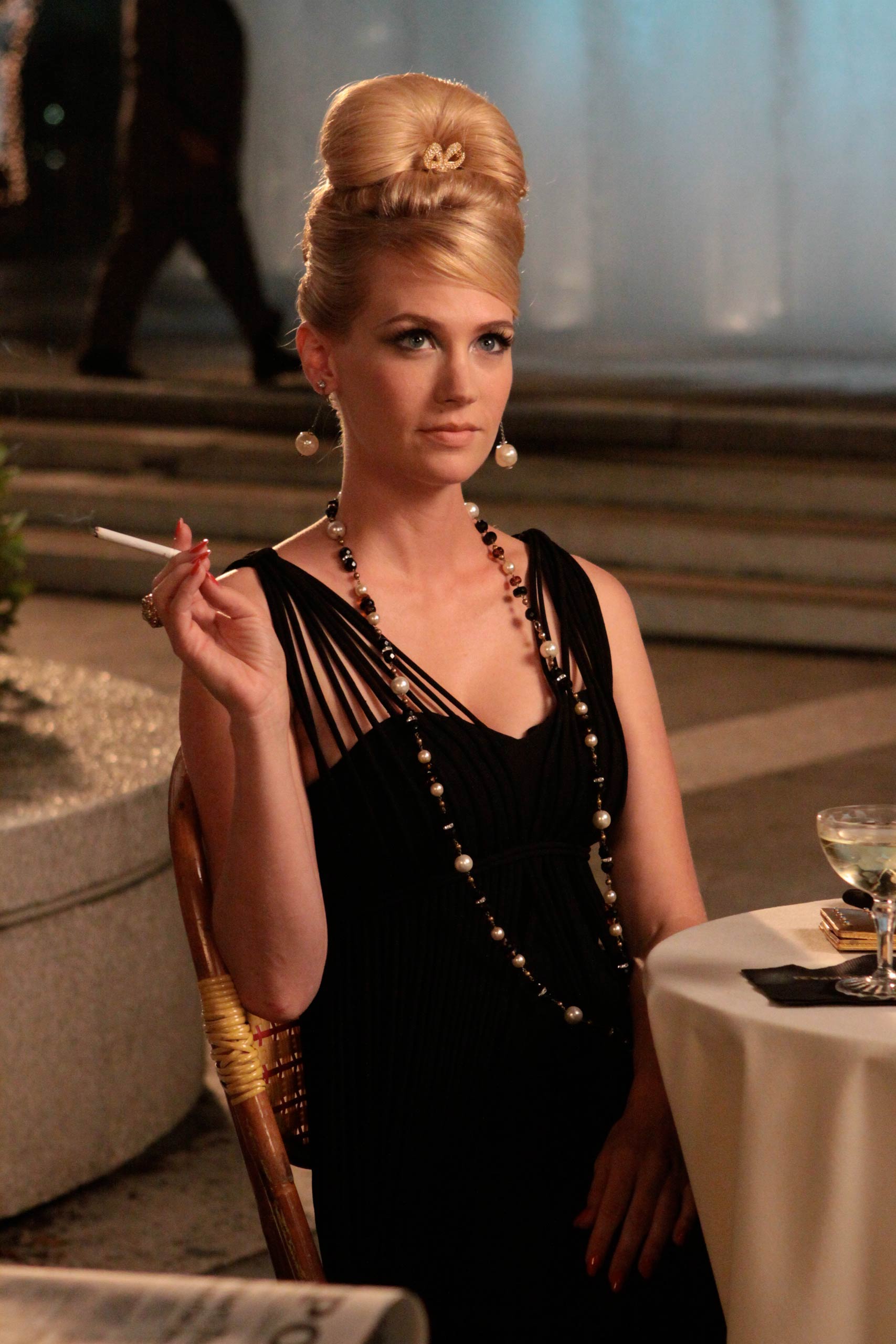

The 10 Best Outfits From Mad Men

At home in Rye (the town Betty moves to with the children when she marries Henry Francis), my grandmother, Mary, had a biography not too different from Betty’s. She was well educated—she had attended the University of Pennsylvania, but had to drop out to care for her younger siblings when her mother fell ill. She went on to work at a magazine, Farm Journal, and like Betty, she modeled—shoes, since she had tiny feet. She stopped working when she settled down, and like many intelligent women of that era, probably would have been happier if she had a life outside the home. She loved the socializing that went with her husband’s job, but she sometimes had Betty’s frostiness with the children—she clearly longed for intellectual stimulation outside motherhood, a case of the feminine mystique.

There were four children in the Wickersham family, not three like the Drapers. The first girl, my mother, is Sally. She calls herself “the original Sally Draper,” and plenty of the show’s scenes match her life. In an early episode, a very young Sally D. serves cocktails at a party at the Draper house. Sally W. and my aunt Sue did the same thing as children in Rye. They would pass out Scotch to the guests, many of them McCann employees, “until the cuteness wore off and we were sent to bed,” my mom says.

Like the young Miss Draper, Sally and Sue had white go-go boots with zippers up the back. Unlike Miss Draper, they were actually allowed to wear them (just not with short skirts).

Lots of female Mad Men fans ask themselves if they’re more of a Joan or a Peggy—the show practically invited such characterization in the early episode “Maidenform,” during a scene about an ad comparing Jackies and Marilyns.

I can easily identify with Peggy in 2015, but back then, would I have been the one in a million who actually broke a glass ceiling? Not likely, and to pretend I would is self-flattery. Odds are I’d be more like Betty and my grandmother: a brief career, marriage, and a quiet, suburban life. Odds are, most of us women would be.

Both my grandparents died when I was in elementary school, and I wish my grandfather had lived longer so I could have heard all of his pitch stories. But even more, I wish my grandmother had lived to see me work in magazines just as she had. We could have talked about her favorite president, Nixon, who has appeared on the cover of TIME more than anyone else, and whose resignation made her cry. And we could have discussed all the authors whose books we’ve seen Betty Draper read: Freud, Fitzgerald, Mary McCarthy. Maybe even Betty Friedan.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com