There are two sets of numbers that tell us a lot about the state of policing in America. This week, the FBI released the latest tally of cops killed in the line of duty. The grim toll in 2014 was 51 law enforcement officers who were killed while doing their jobs (the figure does not include those who died in work-related accidents). That’s an 89% rise from the year before, but still below the average of 64 deaths from 1980 to 2014.

We have those comparisons because the FBI database is considered complete and updated every year. What we don’t know is the corollary number: how many people die as a result of encounters with the police. The FBI does compile a list—the latest shows there were 461 suspects killed in 2013 by police officers, up from 397 in 2010—but it is in no way a comprehensive account because the information is provided voluntarily and only some of the nation’s almost 18,000 police departments contribute. Plus, the FBI’s list is short on details and only specifies the type of weapon used in fatal incidents. Numbers compiled by advocacy groups suggest that the number of people killed by police is much higher, although lower than it once was. According to the New York Times, for example, 91 people were shot and killed by police officers in New York City in 1971 compared with eight in 2013, which was a record low.

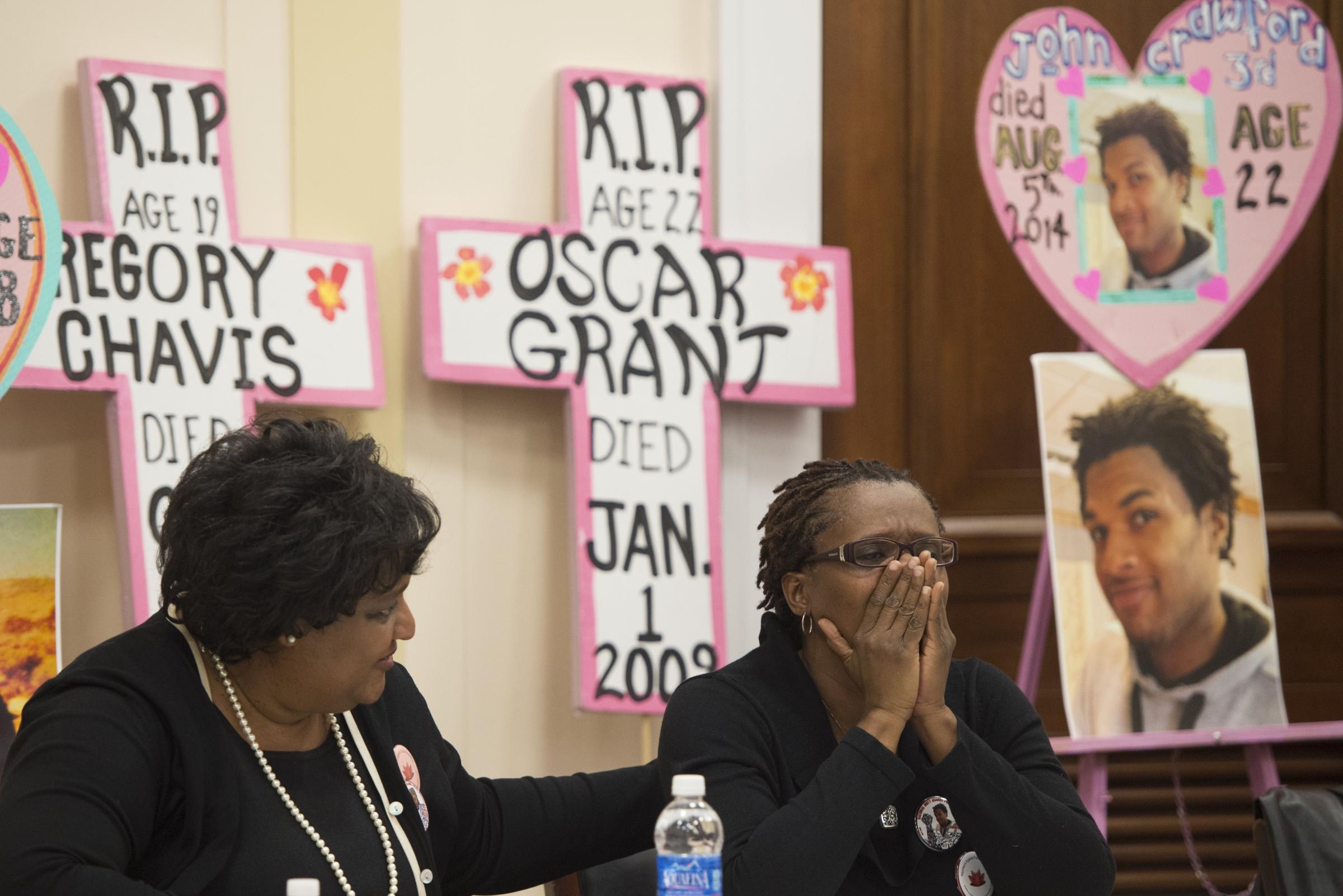

The lack of a reliable, comprehensive database has become a flashpoint in the debate over policing following a string of high-profile fatal incidents involving white officers and unarmed black men. These deaths have led to sometimes violent protests and a renewed focus on police use of force against minorities. And the public response helped prompt FBI director James Comey to call for better data in a speech on law enforcement and race. “The first step to understanding what is really going on in our communities and in our country is to gather more and better data related to those we arrest, those we confront for breaking the law and jeopardizing public safety, and those who confront us,” Comey said.

As the FBI’s new data on officer deaths shows, those confrontations can sometimes be fatal. The most common incident leading to an officer’s death came from answering a disturbance call (11), followed by involvement in car chases or traffic stops (10) and ambushes (8). Others were killed while involved in investigations, tactical situations or dealing with drug-related issues.

“There are certainly cases in the last year that have been directly related to the rise in tensions between police and minority communities,” says Marquette University criminology professor Meghan Stroshine, referring to incidents like one in New York City in December, in which two NYPD officers were deliberately targeted and shot “execution-style” apparently as retribution for police-related deaths of unarmed black men. “We have some cases clearly that were of a retaliatory nature or in the name of correcting perceived past wrongs.”

Just within the last two weeks, several officers have died on duty. The first NYPD officer to be killed in the line of duty since December died on May 4 after being shot by a gunman in Queens. And last week, two officers in Hattiesburg, Miss., were killed during a traffic stop. Four suspects have been charged.

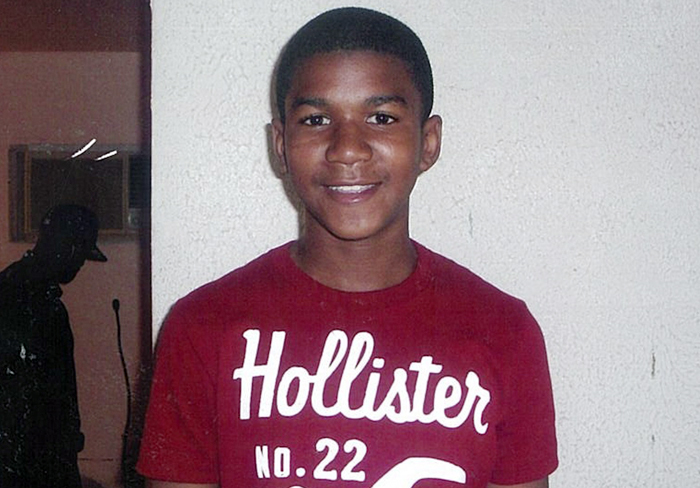

Trayvon Martin

Feb. 26, 2012 Neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman fatally shoots unarmed 17-yearold Trayvon Martin after an altercation in a Sanford, Fla., subdivision. The incident sparked a national conversation about race and prompted President Obama to say that were he to have a son, “he’d look like Trayvon.” Zimmerman, who argued that he acted in self-defense, was acquitted of second-degree murder and manslaughter in July 2013.

Ernest Satterwhite

Feb. 9, 2014 Ernest Satterwhite, 68, is shot and killed in his driveway by a white public-safety officer in North Augusta, S.C., following a slow-speed car chase. Justin Craven fired multiple rounds through the driver-side door of the vehicle. The officer alleges that Satterwhite reached for his weapon; Satterwhite’s family disputes the allegation. Craven was charged with a felony for discharging his gun into an occupied vehicle on April 7, the same day Michael Slager was charged with murdering Walter Scott. He faces up to 10 years in prison.

Dontre Hamilton

April 30, 2014 Milwaukee police officer Christopher Manney fatally shoots Dontre Hamilton, an unarmed 31-year-old African American with a history of mental illness, in a downtown park. Manney alleged that Hamilton, who appeared to be homeless, attempted to grab his baton during a pat down. Manney says he shot Hamilton 14 times in self-defense. Manney was fired in October but was not charged in the shooting.

Eric Garner

July 17, 2014 Eric Garner, 43, dies after being wrestled to the ground as New York City police attempted to arrest him for selling illegal cigarettes. In a cell-phone video recorded by a bystander, Garner can be heard repeatedly saying, “I can’t breathe.” The phrase was soon adopted as a rallying cry by protesters. On Dec. 3, a grand jury decided not to indict NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo in Garner’s death.

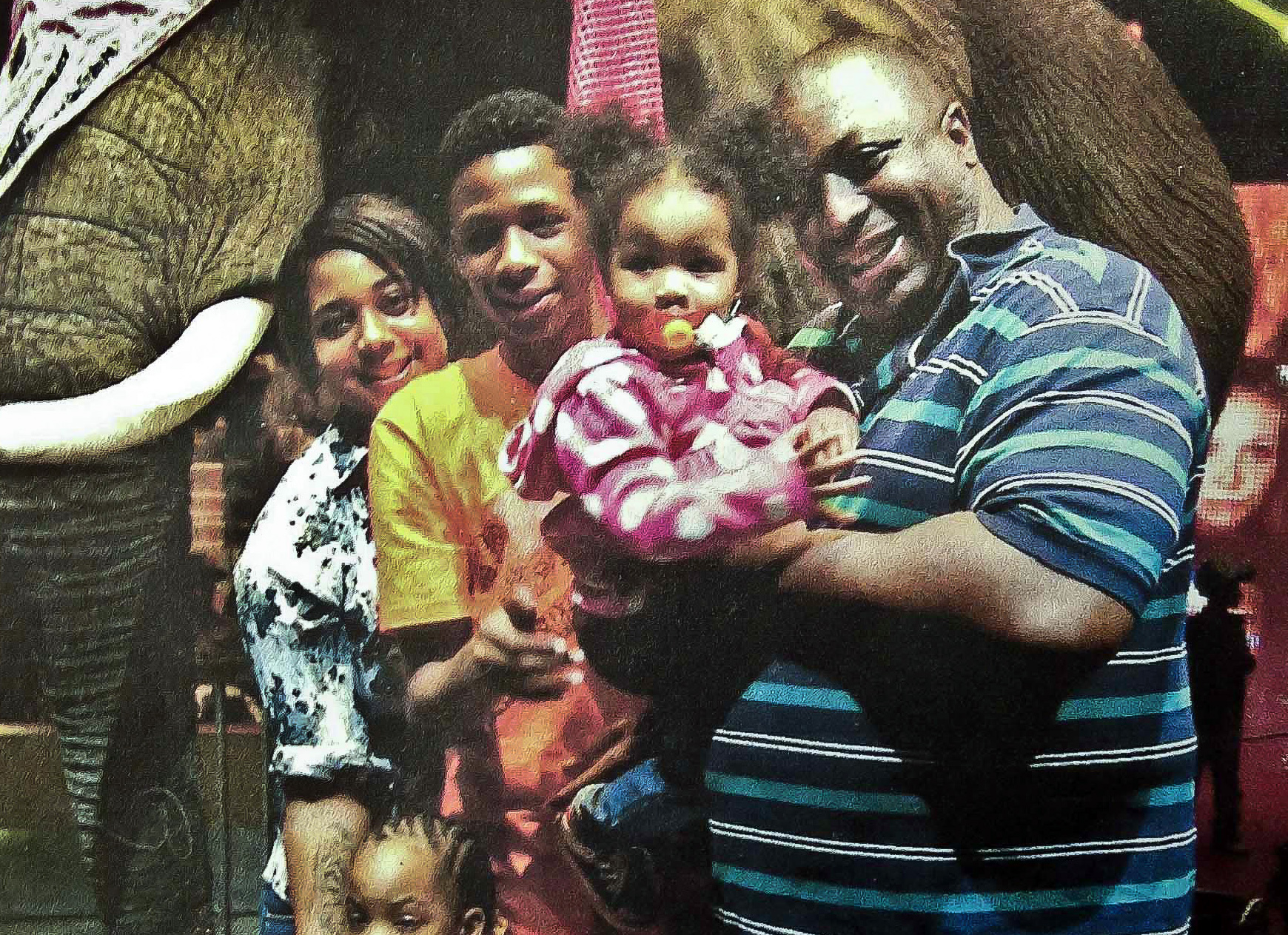

John Crawford III

Aug. 5, 2014 John Crawford III, 22, is shot inside a Walmart in Beavercreek, Ohio, after picking up an air rifle from the shelf. While police say they repeatedly asked Crawford, who was black, to drop the gun, surveillance video shows that police shot the man soon after approaching him.

Michael Brown

Aug. 9, 2014 Darren Wilson, a white Ferguson, Mo., police officer, fatally shoots unarmed 18-yearold Michael Brown, setting off months of unrest in the St. Louis area. Protests erupted nationwide in November, when Wilson was not indicted in Brown’s death. But the shooting prompted a Justice Department investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. In March, after the scathing report found instances of overt racism among officers and a pattern of arrests targeting black residents, Ferguson’s police chief and city manager resigned.

Levar Jones

Sept. 4, 2014 Levar Jones, 35, is shot multiple times by 31-year-old Sean Groubert, a white South Carolina state trooper, seconds after being stopped for a seat-belt violation, all of which was caught on the officer’s dash cam. Jones, who was black and unarmed, survived and can be heard on a video asking, “Why did you shoot me?” Groubert was later fired and charged with assault and battery, which carries a sentence of 20 years in prison. A verdict is expected later this year.

Tamir Rice

Nov. 22, 2014 Tamir Rice, 12, is fatally shot and killed in a Cleveland park after police responded to a 911 call reporting a person with a gun. The caller warned that the gun may have been fake, but the officers say they didn’t know that. Officer Timothy Loehmann shot Rice within seconds of arriving on the scene. Rice’s gun turned out to have been a toy. A group of political and religious leaders have called for criminal charges to be brought against the officers involved, and a grand jury plans to hear evidence in the case.

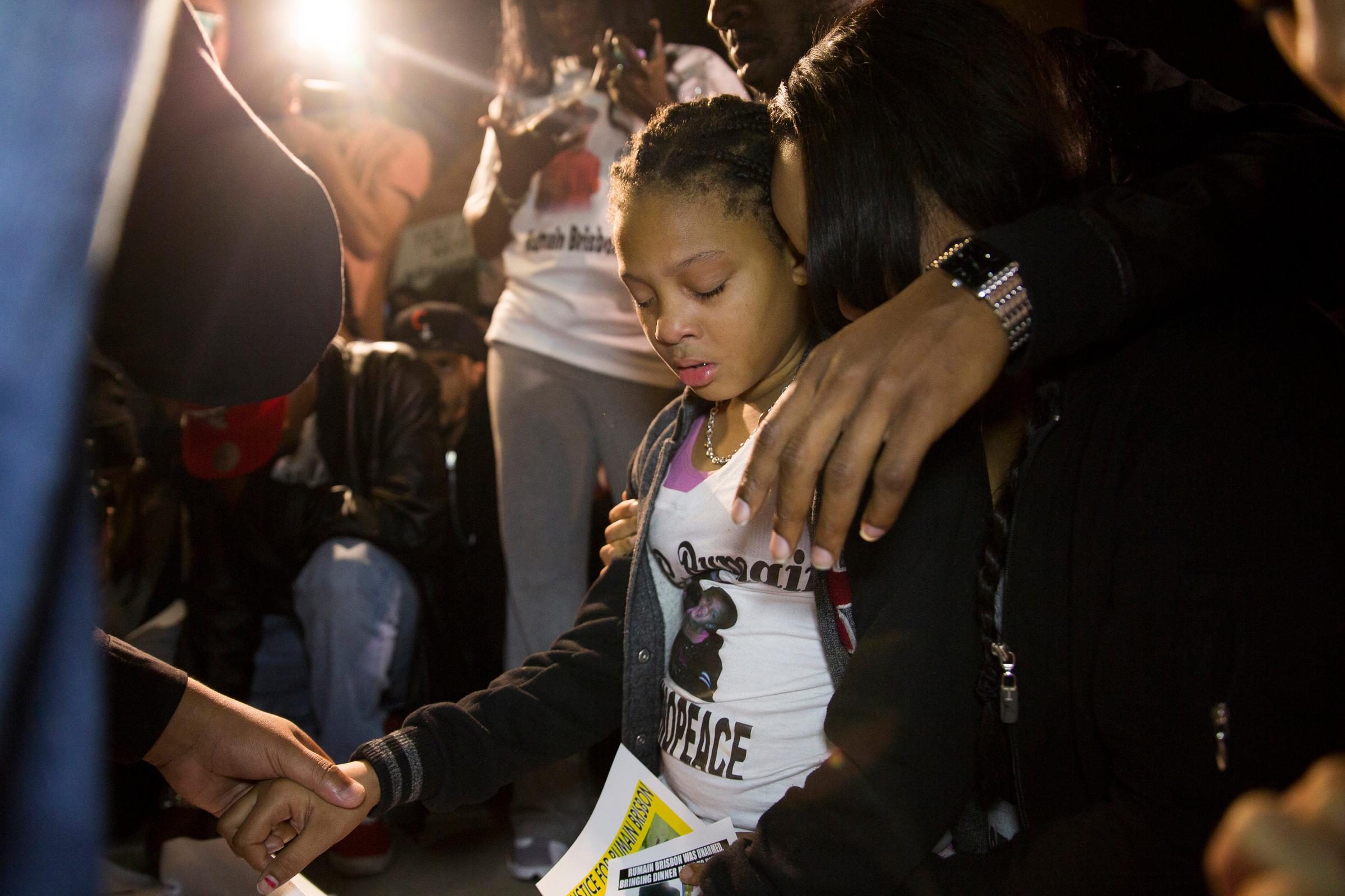

Rumain Brisbon

Dec. 2, 2014 Rumain Brisbon, 34, is shot and killed by a Phoenix police officer following a drug-related traffic stop in which Brisbon, who was black, fled, refused arrest and appeared to be reaching for a weapon. Brisbon was shot by Mark Rine, a 30-year-old white officer. The incident set off several demonstrations in downtown Phoenix. On April 1, a Maricopa County attorney announced that criminal charges would not be brought against Rine.

Charly “Africa” Leundeu Keunang

March 1, 2015 Los Angeles police officers shoot and kill a black homeless man named Charly “Africa” Leundeu Keunang, following a confrontation in the city’s Skid Row, an area with a heavy concentration of homeless people. Officers said the man attempted to take one of their guns.

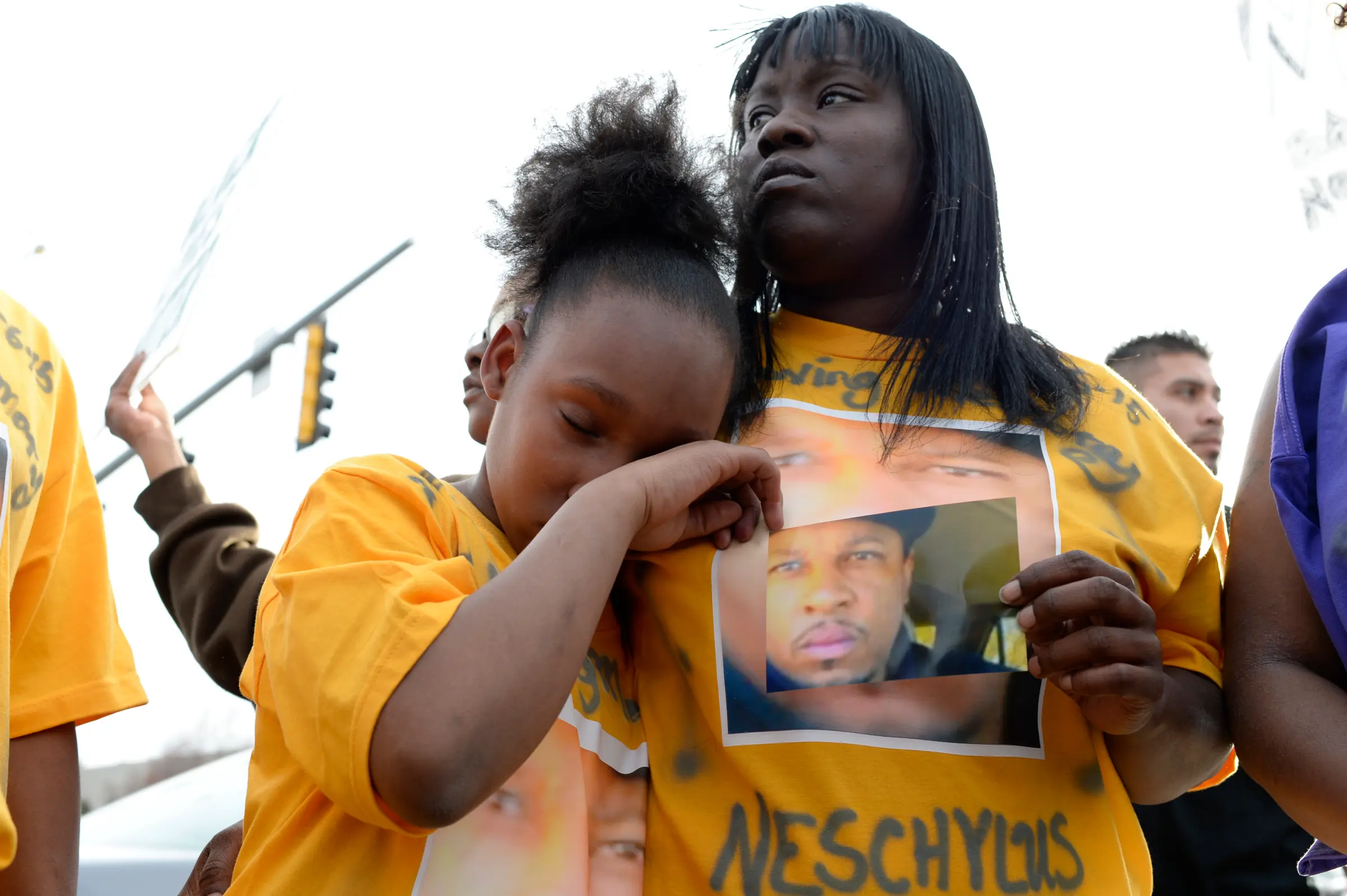

Naeschylus Vinzant

March 6, 2015 Naeschylus Vinzant, a 37-yearold unarmed black man, is shot in the chest and killed by Paul Jerothe, a police officer in Aurora, Colo. At the time of the shooting, Vinzant was violating his parole and had removed his ankle bracelet. He also had a violent criminal history but was unarmed as officers tried to arrest him. Jerothe, a SWAT team medic officer, has been placed on administrative leave pending an investigation.

Tony Robinson

March 6, 2015 Tony Robinson, a 19-year-old biracial man, is shot by a white Madison, Wis., police officer after Robinson was allegedly jumping in and out of traffic. Matt Kenny, a 45-year-old officer who was exonerated in a 2007 shooting of an African-American man, got into an altercation with Robinson when he entered an apartment in which Robinson was reportedly acting aggressively. Kenny, who says he was attacked by Robinson, was placed on administrative leave with pay pending the results of an investigation.

Anthony Hill

March 9, 2015 Anthony Hill, a black 27-yearold Air Force veteran, is shot and killed in Chamblee, Ga., by Robert Olsen, a white DeKalb County Police Department officer. Hill was naked and unarmed at the time of the incident and was apparently knocking on multiple apartment doors inside a housing complex. Olsen has been placed on leave. An investigation by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation is currently under way.

Walter Scott

April 4, 2015 Walter Scott, a 50-year-old black man, is shot and killed as he’s apparently fleeing North Charleston officer Michael Slager, 33. Slager, who is white, alleges that Scott reached for his Taser. A video recorded by a bystander appears to show Scott running away from the officer as he’s shot in the back eight times.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com