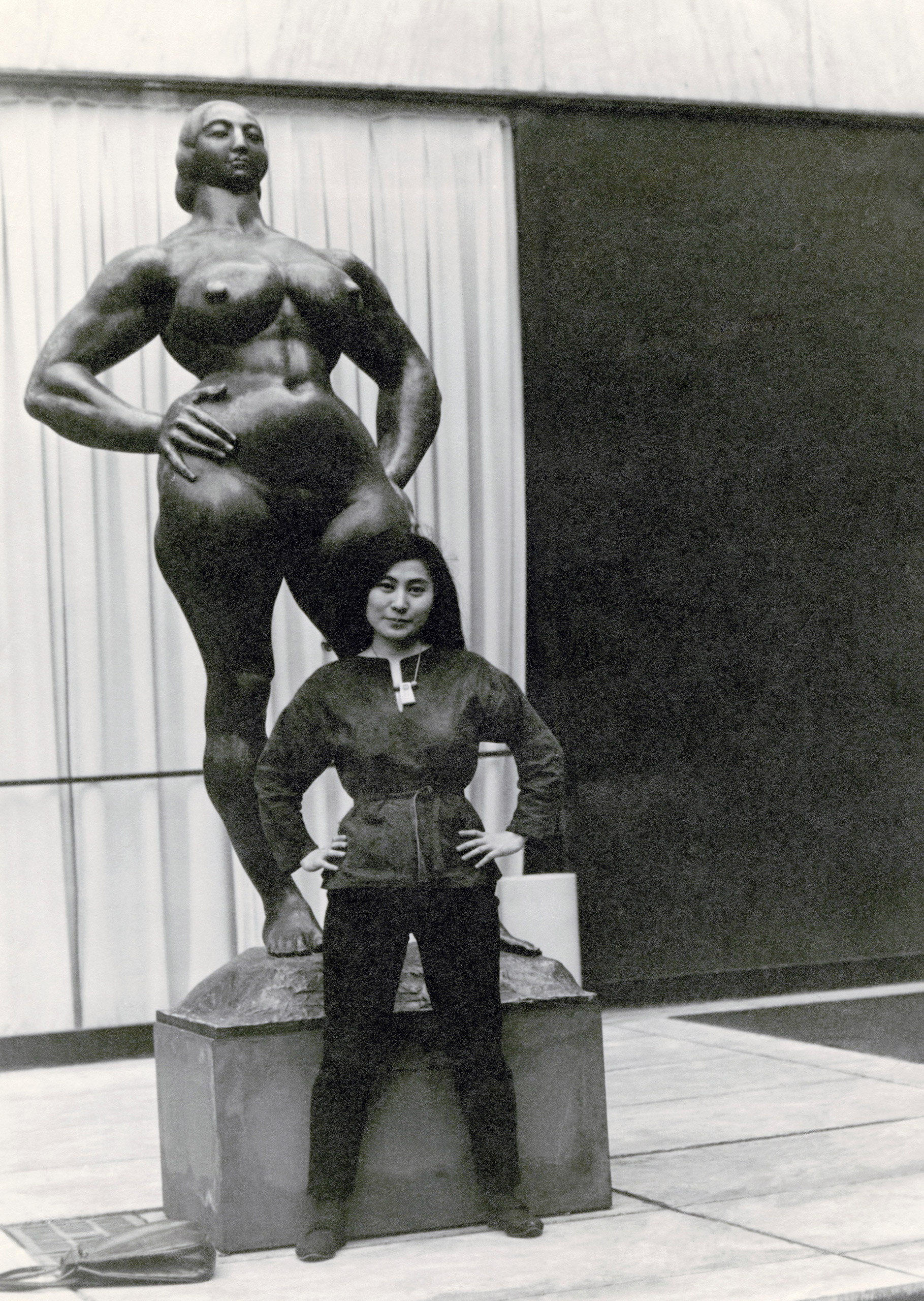

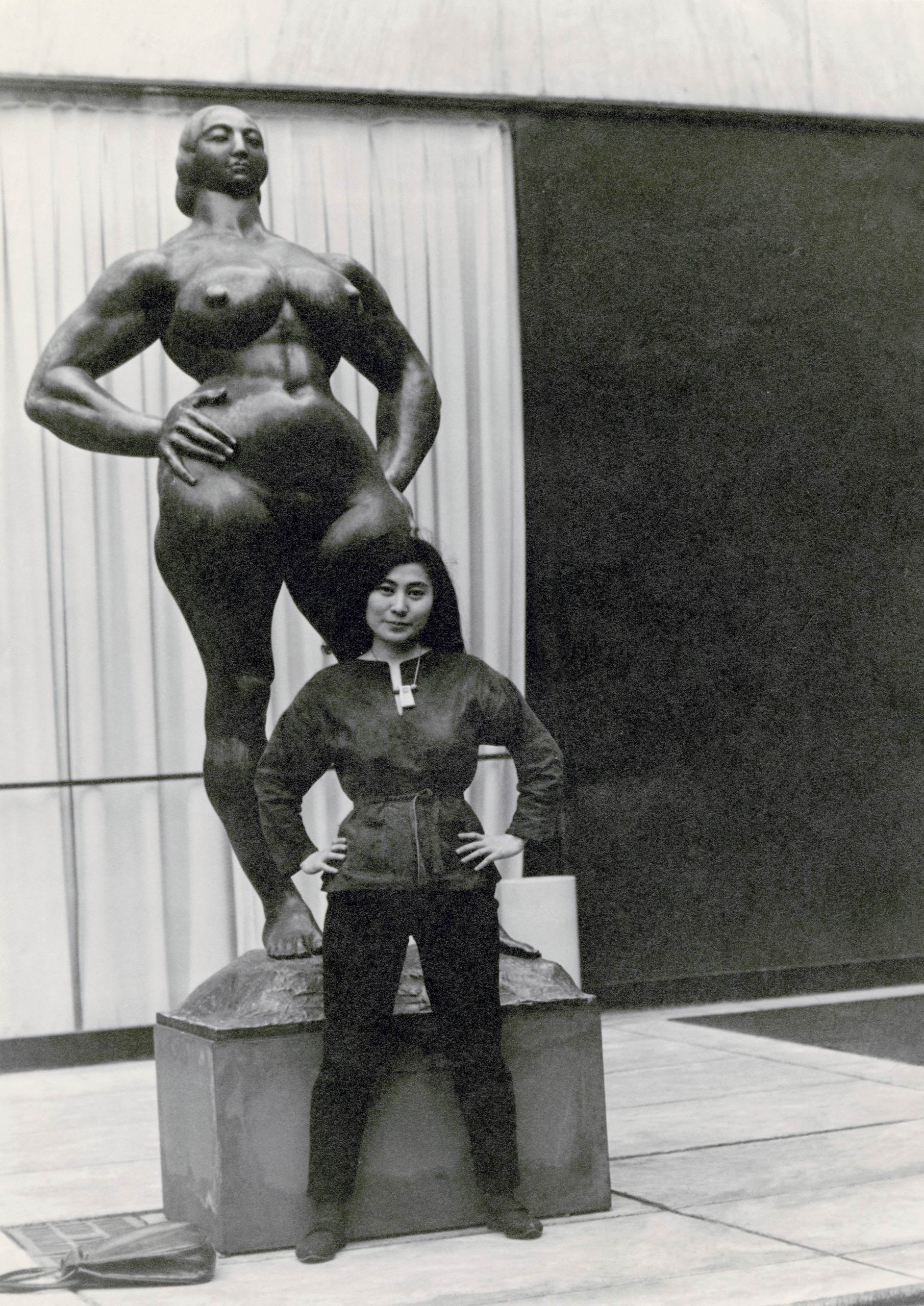

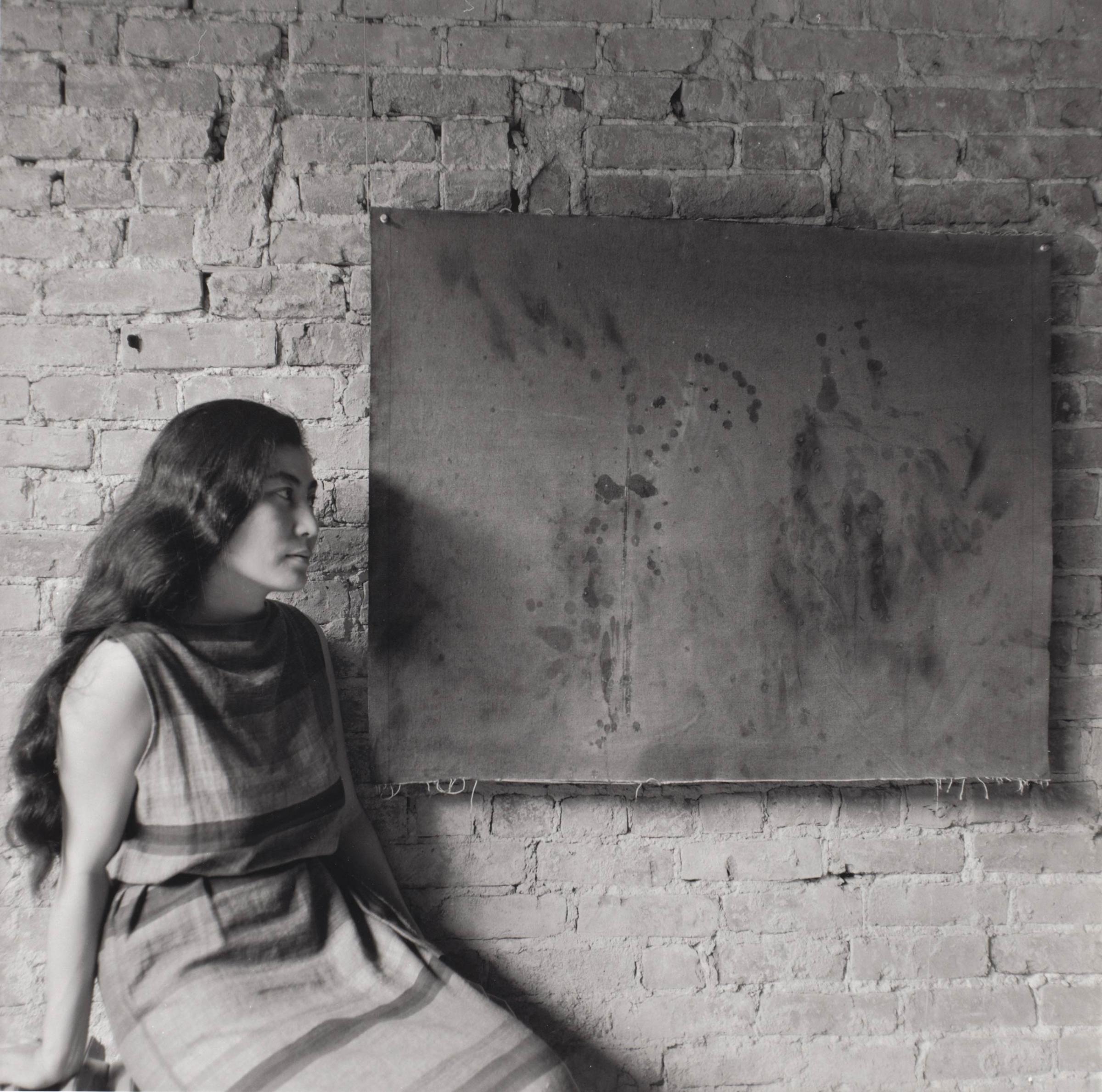

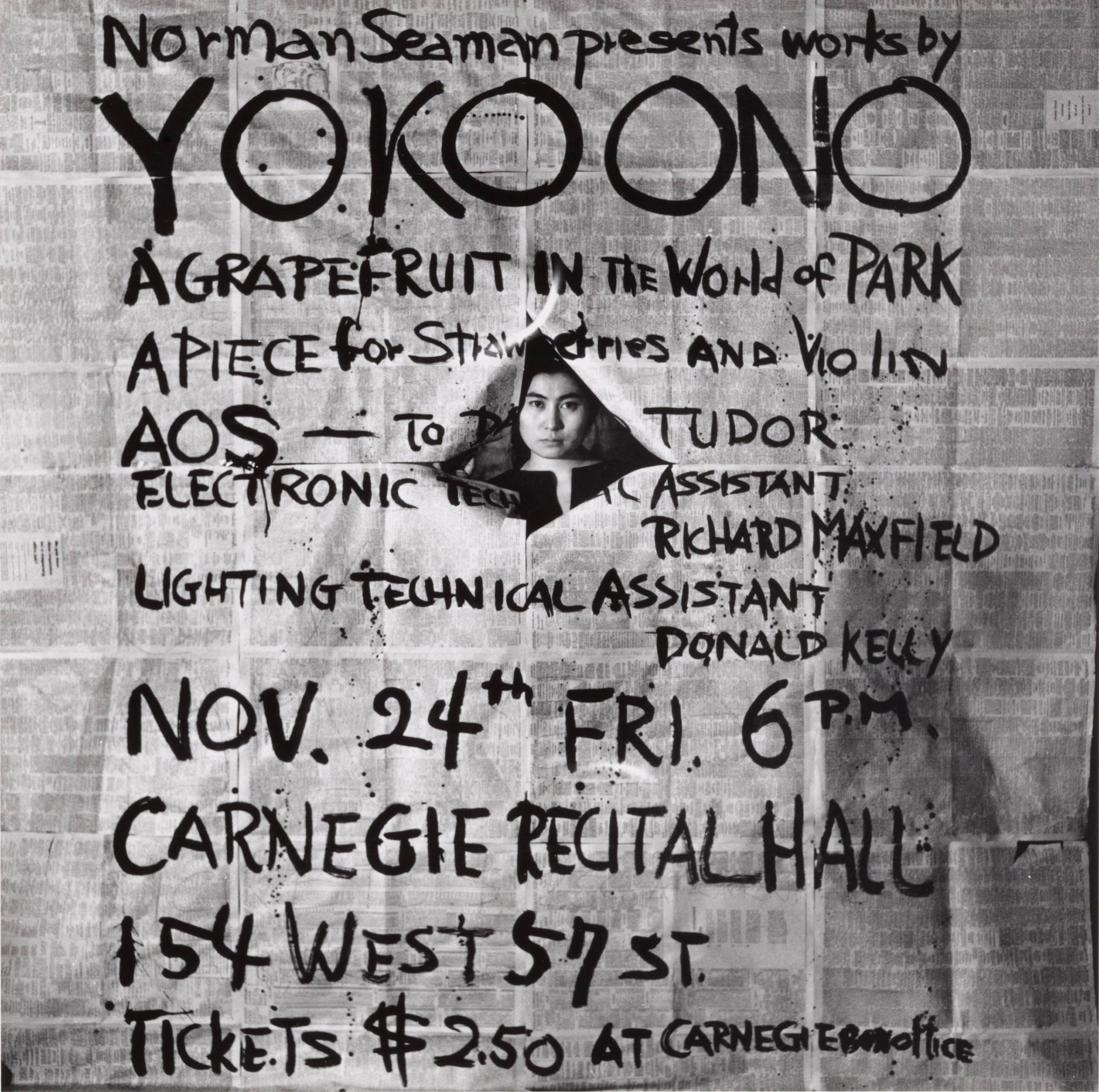

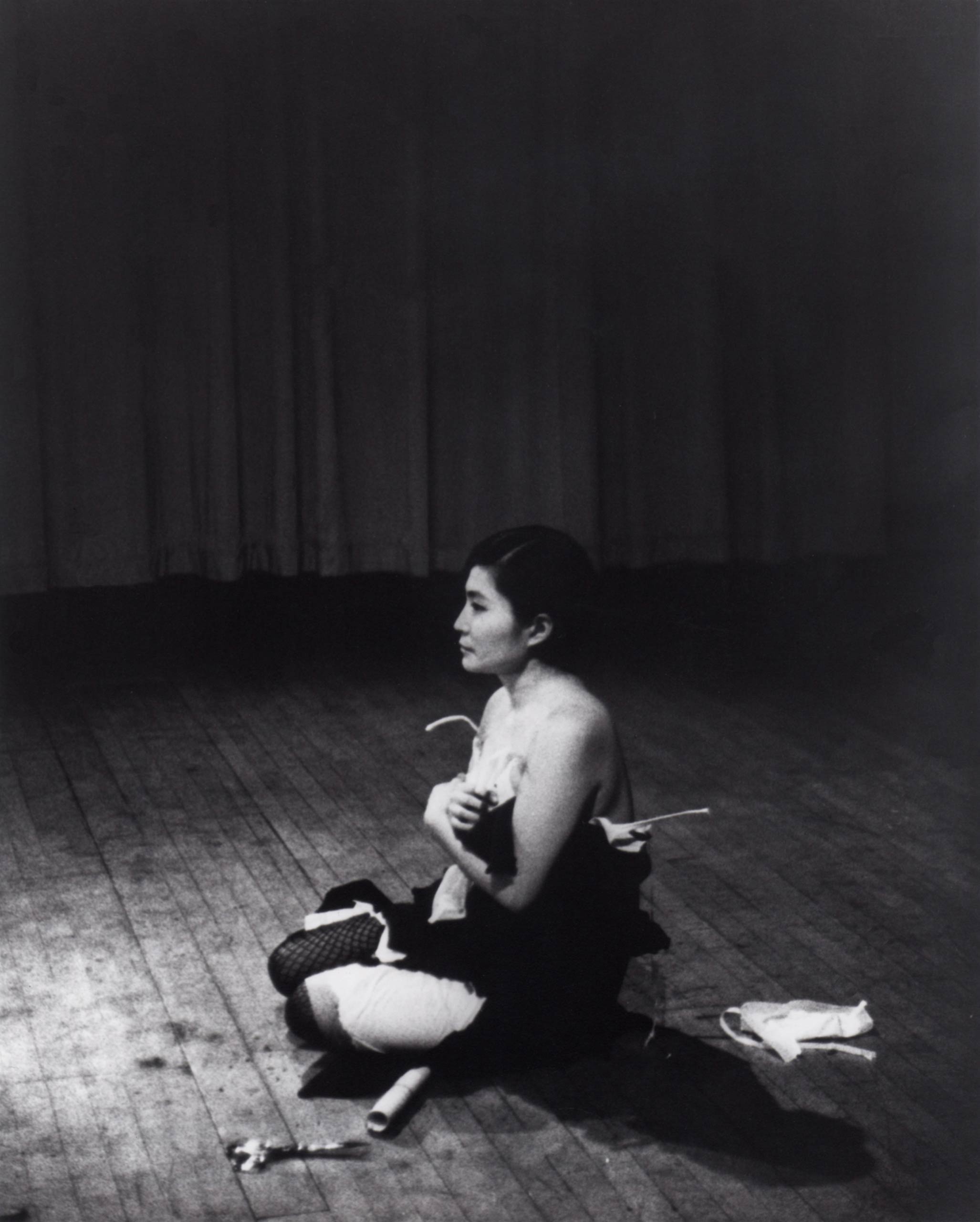

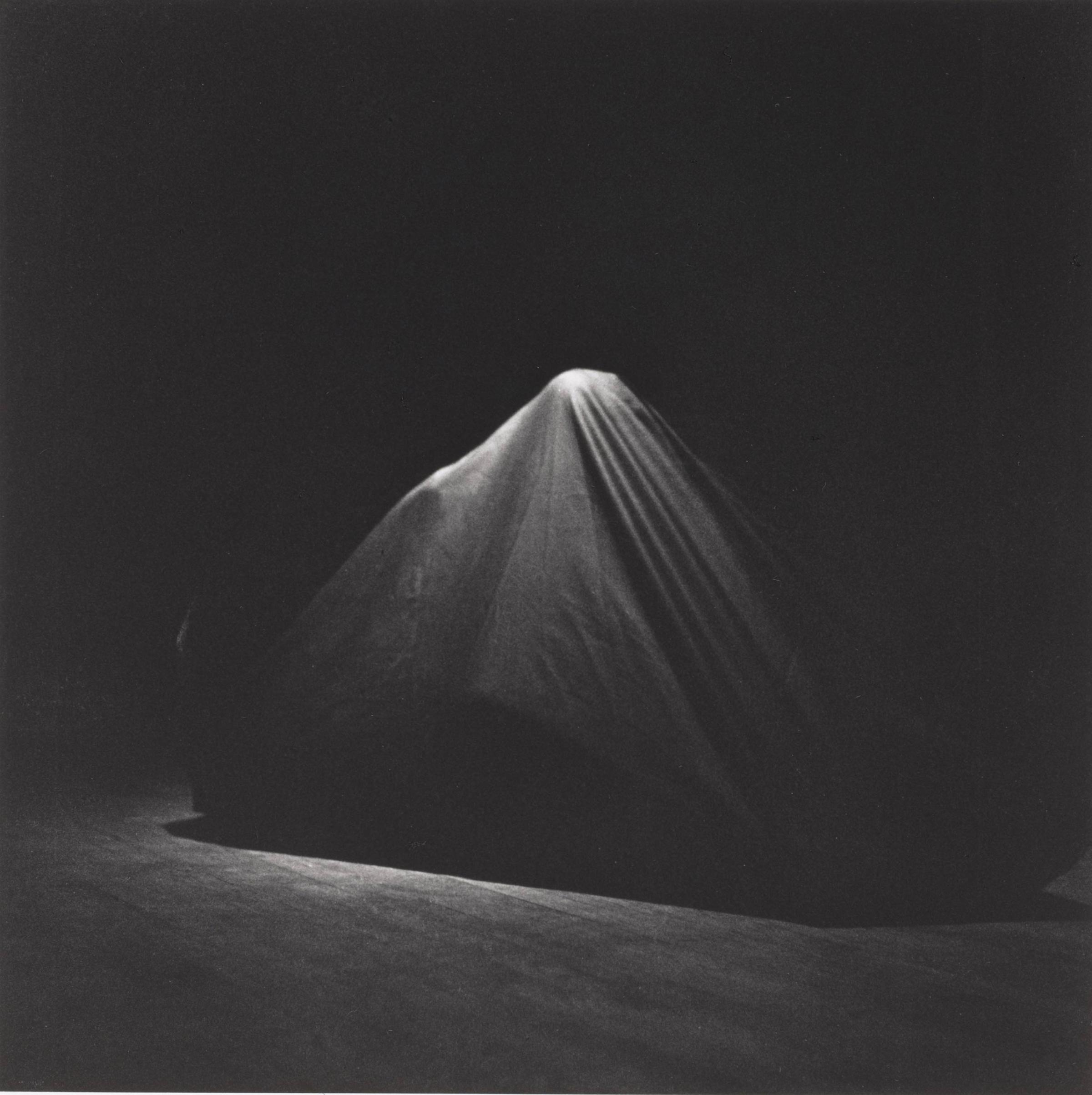

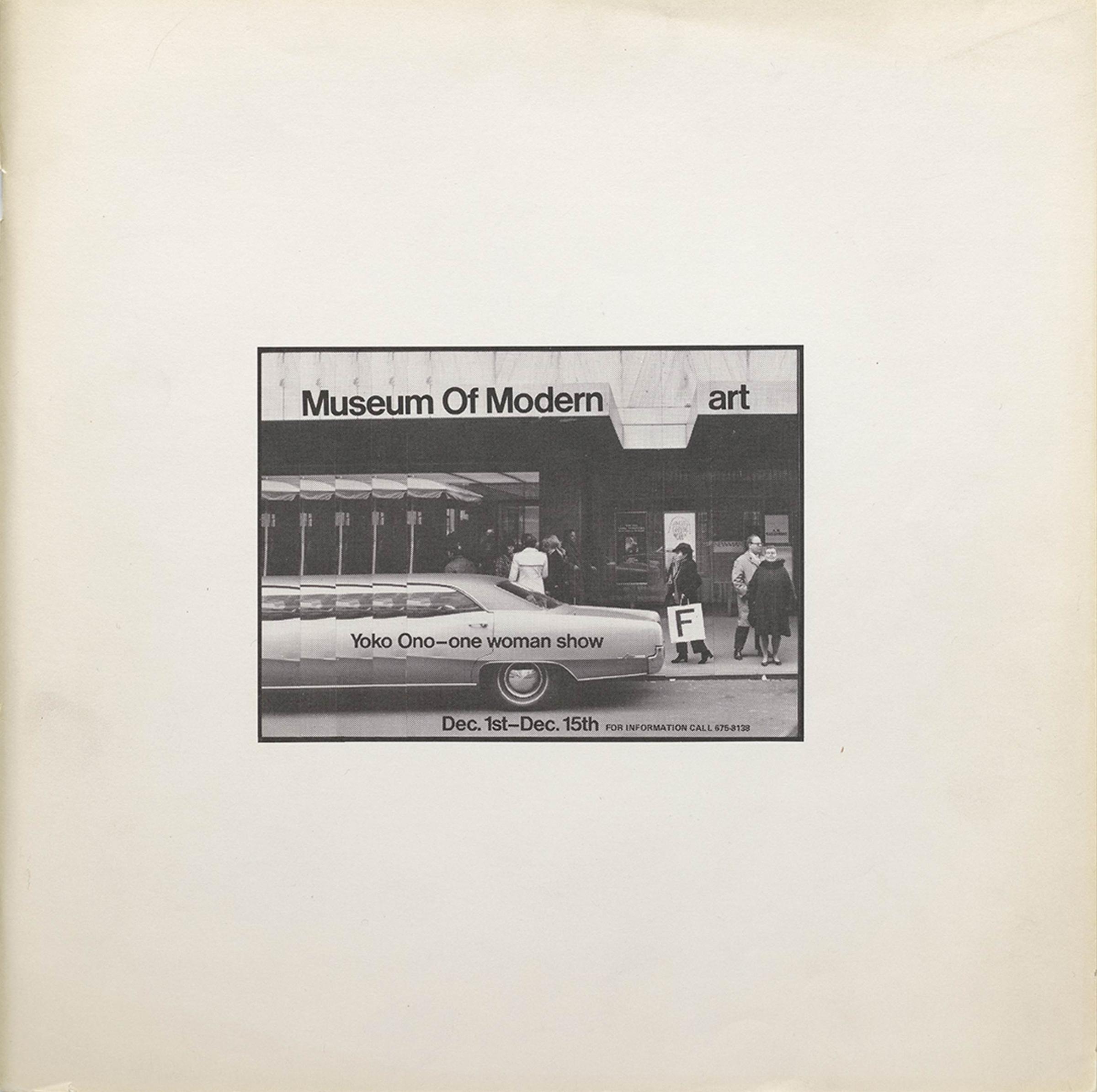

Yoko Ono made her “unofficial” debut at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1971, by advertising a “one woman show” that didn’t actually exist. What a difference four decades makes. “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971,” a new MoMA exhibition of her work opening May 17, is a belated recognition of the importance of Ono’s conceptual and performance art in the 1960s.

But MoMA isn’t the only institution that did not give Ono much attention in the years before her name was linked to John Lennon’s. Her early work was pretty far out, and it was clear that not everybody got it.

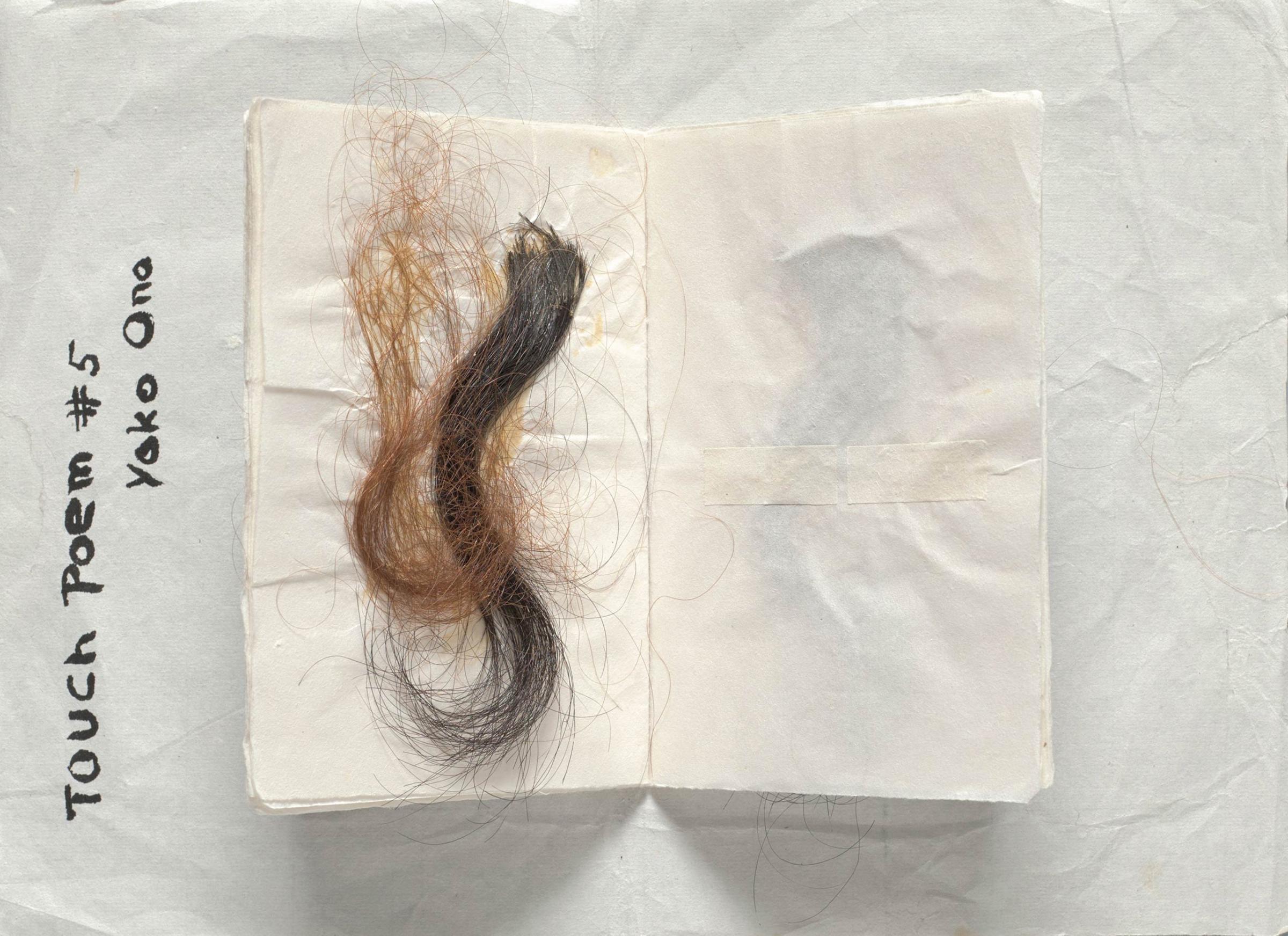

Case in point: When Ono made her first appearance in TIME in 1966 as part of a report on the scene at a week-long “Destruction in Art Symposium” in London, the magazine’s eye-rolling tone was clear as it described her “fey Zen variant on the dominant theme” to “spread out a cloth on which she drew the outlines of people’s shadows, then [fold] it up to take their shadows prisoner.”

See Photos From Yoko Ono's MoMA Exhibit

A year later, Ono merited a paragraph under the headline for her recent “show-biz flop.” As TIME reported:

In London last week, a widely heralded underground film called No. 4 had its world premiere, showing nothing but some 300 nude British buttocks, a fresh one every 15 seconds or so for 76 minutes. For sound track, there were the taped comments of the volunteers. “I’m a bit cynical about mine,” said a girl who described herself as a model, “because it’s worth money.” The director was Miss Yoko Ono, 34, a Tokyo-born artist-composer and currently an entrepreneur of happenings in London. The premiere was a benefit for Britain’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, a prestigious public patron headed by eminent Art Philosopher Sir Herbert Read. But the point of it all was lost on most Londoners. Sales of the opening-night tickets ($4.20 top) were so slow that many had to be given away. The most appreciative audience response came ten minutes (and 40 rumps) along, when a spectator leaped onstage and stroked the screen image. By the halfway point, fully two-thirds of the first-nighters had departed.

By 1968, she had become linked with Lennon, first as a “free female soul” with whom he was opening an art exhibit—and soon after as the avant-garde artist for whom he was leaving his wife Cynthia. Decades later, though her relationship with Lennon has remained a defining element of her public life, the museum at which she was once able to mount only a theoretical show is giving her a real solo exhibition.

Among the pieces on show: Film No. 4.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com