After the Soviet Union splintered in 1991, I took a few days off from my job at the White House and visited St. Petersburg, Russia. Strolling through the flaking walls of the Hermitage, I realized that communism’s problem was not that it was failing to keep up with the rising standards of 1980s America. The Soviets could not keep up with the standards of 1917 Russia! I’m reminded of that now. Next week, the musical Doctor Zhivago will premier on Broadway at a time when Russian President Vladimir Putin seems to be rolling back the clock on liberty, and many Russians worry that their country’s economy is sliding backwards.

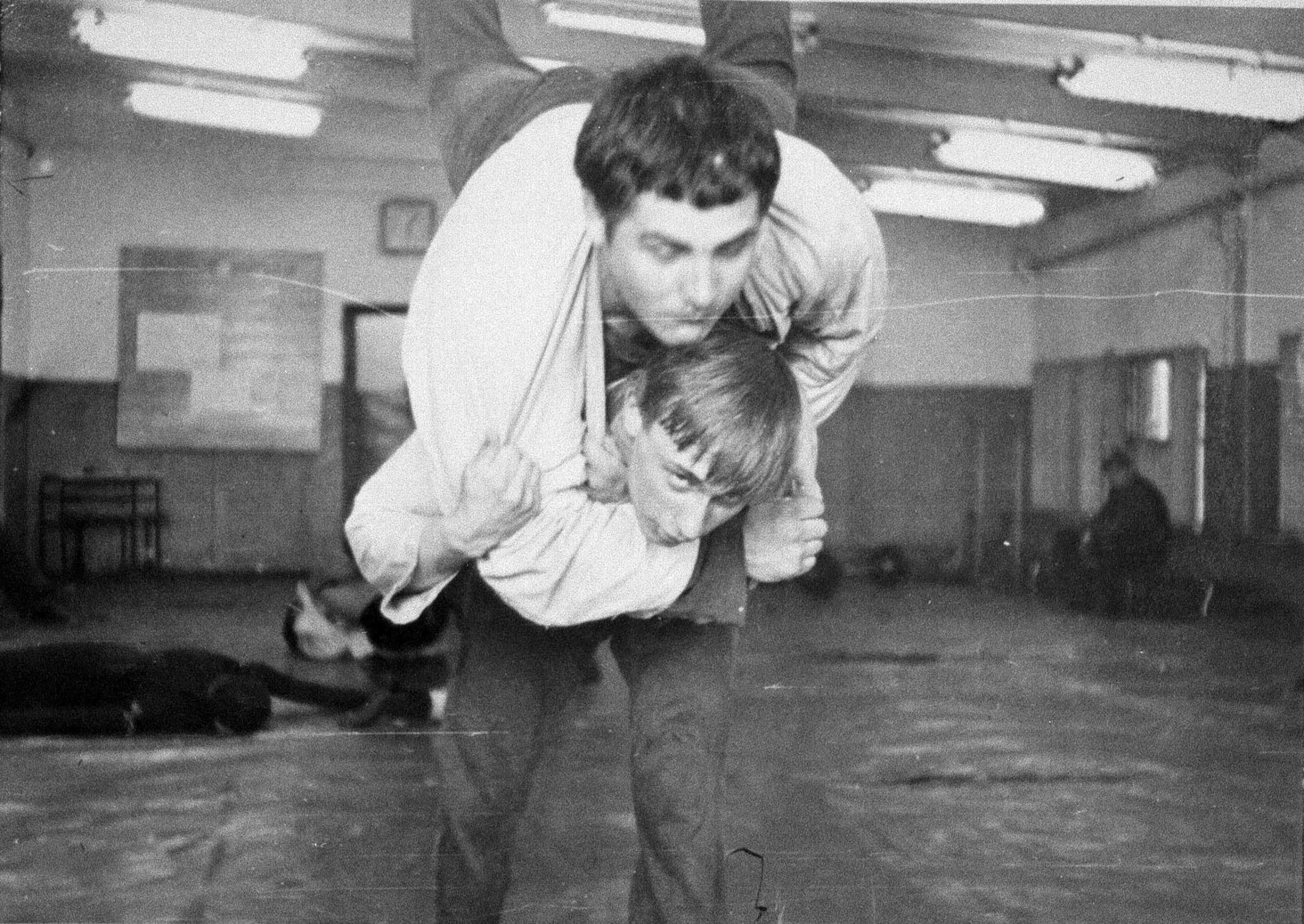

I doubt that Putin will be buying a front-row seat for opening night. For one thing, he appears to prefer judo takedowns and bare-chested bronco riding to songs and waltzes. There’s also the fact that during the Cold War, the Central Intelligence Agency used Boris Pasternak’s 1957 novel to inject subversive ideas into the minds of the Soviet public: ideas such as love and exalting individual choice over the state.

The true story of the manuscript’s return to Russia through the work of CIA agents is almost as powerful as the story itself. Last year, the CIA revealed that in 1958, Britain’s MI6 funneled a secret package to CIA headquarters. Agents pulled out two rolls of film from the package – photos of Pasternak’s banned text, and the CIA quickly funded printing presses and began sneaking the novel into the hands of Russians. Russian attendees grabbed copies of Doctor Zhivago as if they were rare and coveted Levi jeans.

Why does Doctor Zhivago still resonate in Russia more than 55 years later? In the novel, the poet and doctor Yuri Zhivago has been robbed of his title and privilege. But the bigger loss is Russia’s: When the communists trampled on the bourgeois, they also trampled on Russian history and culture. Pasternak had seen the thuggish bureaucrats at the Union of Soviet Composers ban the subversive cadences of Igor Stravinsky and of Sergei Rachmaninoff, who fled for Helsinki on an open sled in 1917.

Zhivago represents the powerful romantic strain in Russian history: the sweeping melodies of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and the heartbreaking prose and poetry of Alexander Pushkin and Leo Tolstoy. To which the Soviet Union and, more recently, Putin’s nationalistic Russia have added, what exactly? Sputnik? A bombastic Olympics opening ceremony? A banning of the punk rock girl band Pussy Riot? There is still greatness in the Russian people – hearty laughs and heaving tears ready to be tapped. But they have been bottled up for 100 years.

Take a look at the moving videos of pianist Vladimir Horowitz’s return to Moscow in 1986. Russian music students nearly storm the gates to see the aged maestro who had fled as a wunderkind in 1925, his only money stashed inside his shoes. Tears stream down the cheeks of old people. Horowitz recalls for them the monumental and long-missed triumphs of Russia’s 19th century romantics.

In Doctor Zhivago, Putin might even see himself – and his potential for redemption. In the beginning of the text, Lara’s husband is known as Pasha, who is collegial and searching for truth. Later he shows up morphed into the monstrous and authoritarian Strelnikov. In the musical, after the transformation, he sings a villainous song, “No Mercy at All.”

Is Putin a reborn Pasha/Strelnikov? After an undistinguished career at the KGB, he resigned and became a deputy mayor in St. Petersburg. He was a leader of the reformist “Our Home is Russia” party before moving to Moscow to serve Boris Yeltsin. In 1999 he described communism as a “blind alley.” In June 2001, President George W. Bush said he “looked the man in the eye,” and found him to be “trustworthy. … I was able to get a sense of his soul.” After 9/11, Putin and Russia helped the U.S. hunt down terrorists. And as U.S. troops were flying to Afghanistan, a White House official told me that Putin’s Russia was “our northern alliance.” That was Putin’s cooperative Pasha period.

Now we move to Putin’s Strelnikov period. This is a Russia where opponents are shot and poisoned with polonium, where nationalist troops in disguise storm across Crimea, and where Putin asks historians why they frown upon Ivan the Terrible and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the Nazis. Surely, Putin is as wily and unpredictable as any literary character.

But unlike a Broadway musical, Putin has a third act. What will it be? With the price of gold and the value of Russian exports sinking, the Russian economy is shaky, and the ruble has lost half its value against the U.S. dollar. Putin used to appear shirtless because he was boasting about his physique. Now he might appear bare-chested because he’s had to sell his shirt. President Barack Obama came to office promising a “reset” of Russian-U.S. relations. They did reset – but at a far worse level. Now, it is up to Putin to reset himself. He could do worse than to buy a front row seat for Doctor Zhivago’s opening night on Broadway.

Todd G. Buchholz is a former White House economic adviser and recipient of the Allyn Young Teaching Prize at Harvard. He is co-writer of the new musical about the Italian Resistance against Fascism “Glory Ride” and writes a blog.

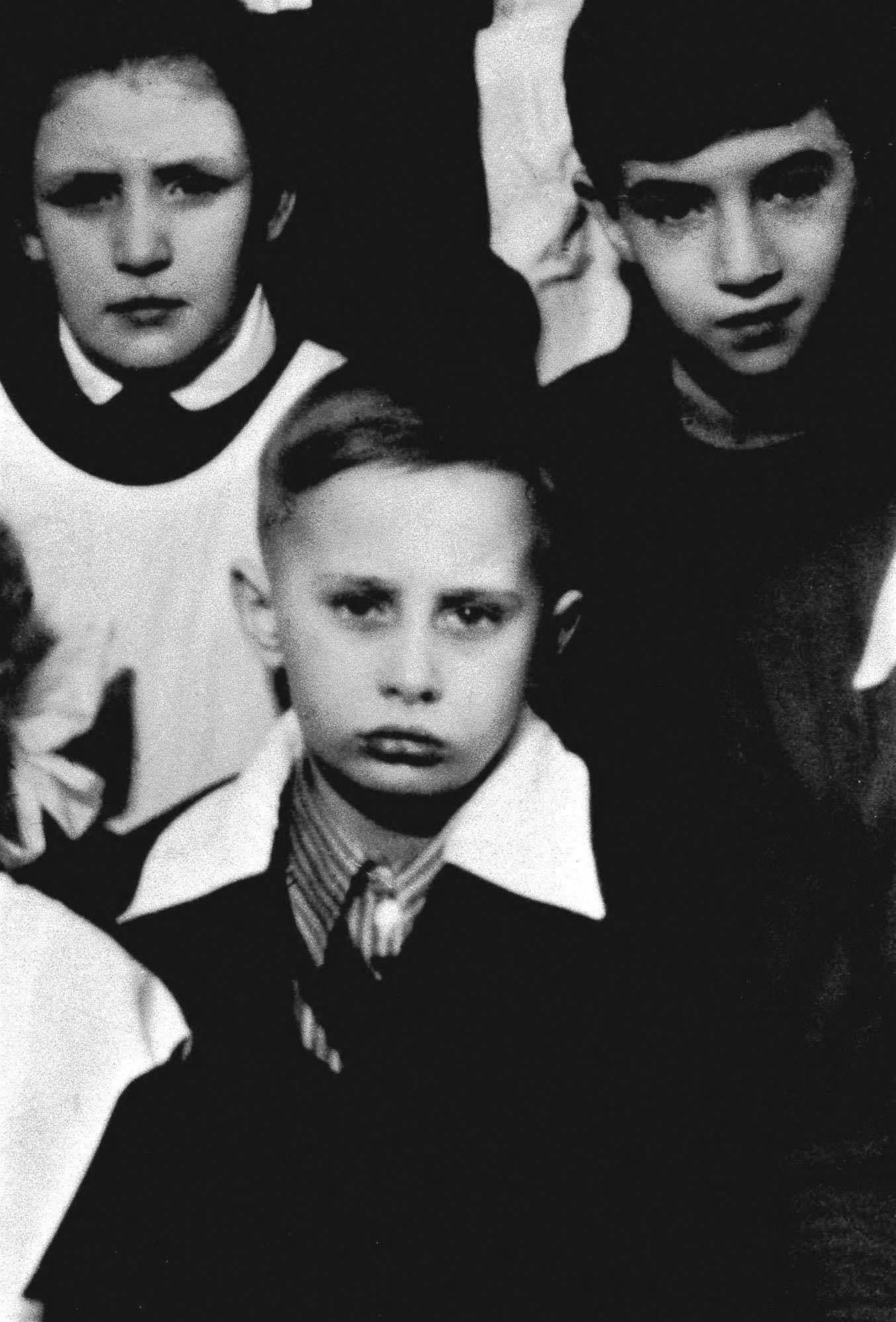

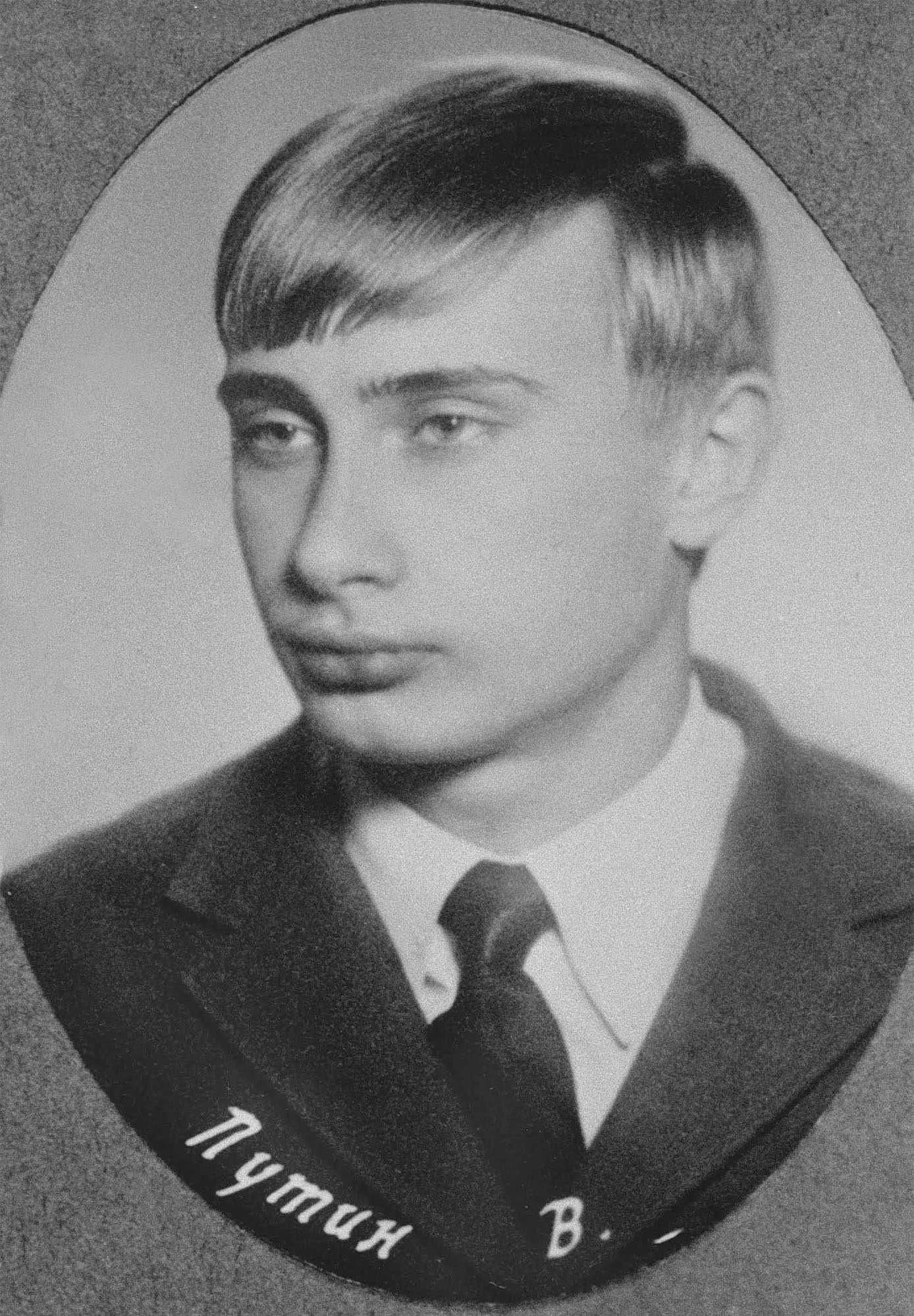

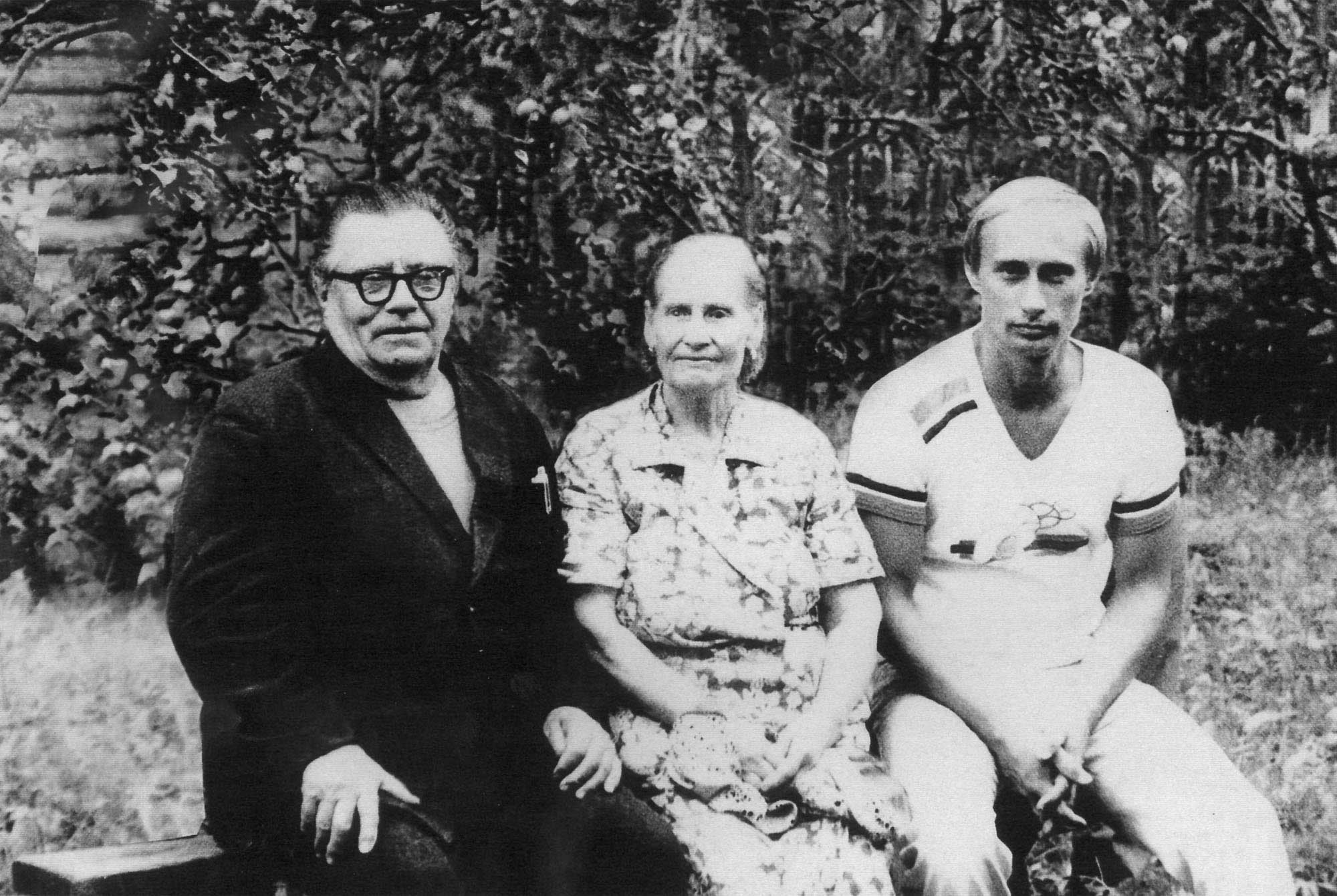

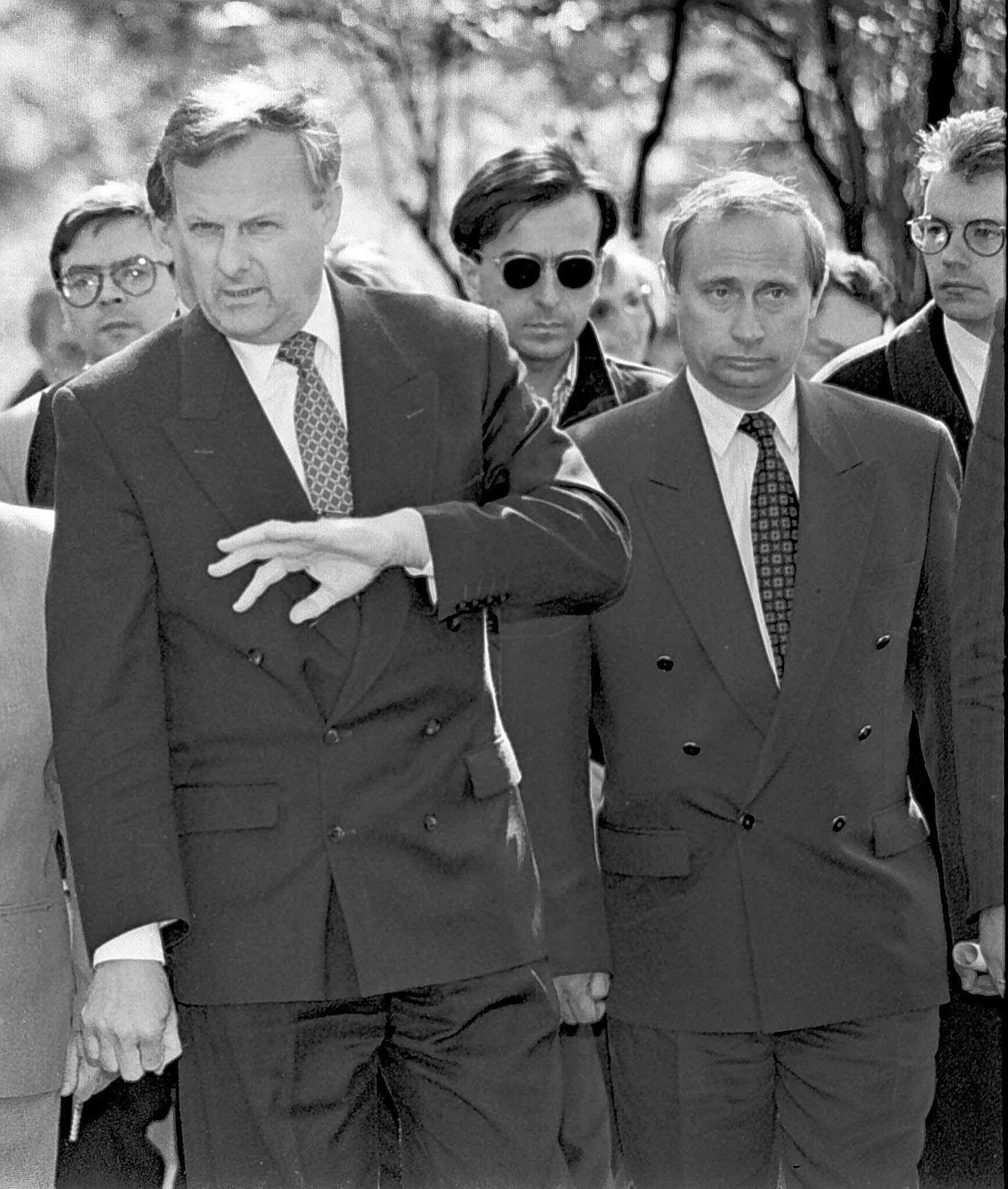

See Pictures of a Young Vladimir Putin

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com