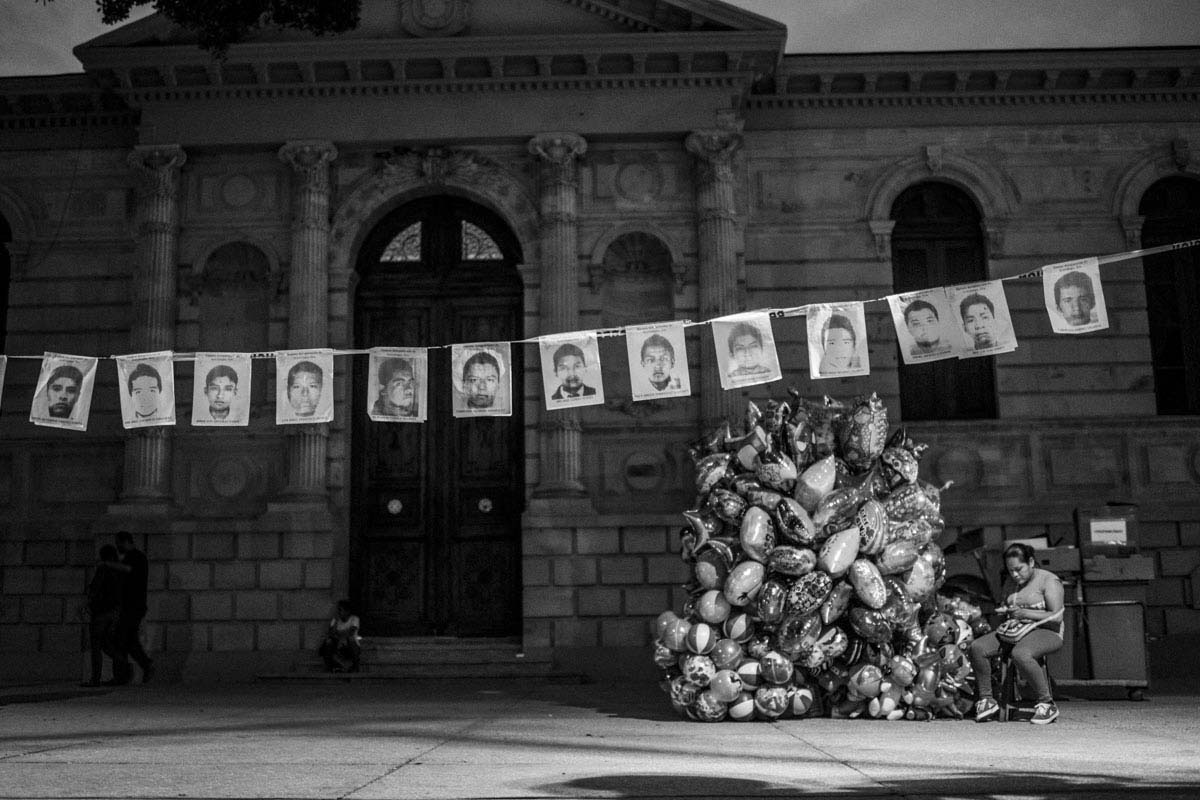

On Sept. 26, a drug gang, aided by corrupt police officers, allegedly abducted and killed 43 students in Mexico’s Southern Guerrero state. The assassins incinerated their corpses for more than 14 hours before discarding their remains into plastic bags and throwing them in a nearby river.

“Even before I arrived here, I was shocked by this story,” says photographer Sebastian Liste, who was on assignment for TIME. “But it’s only when I got to Mexico that I understood how important this event would be for this country’s contemporary history, so I was very interested and motivated to work on this story.”

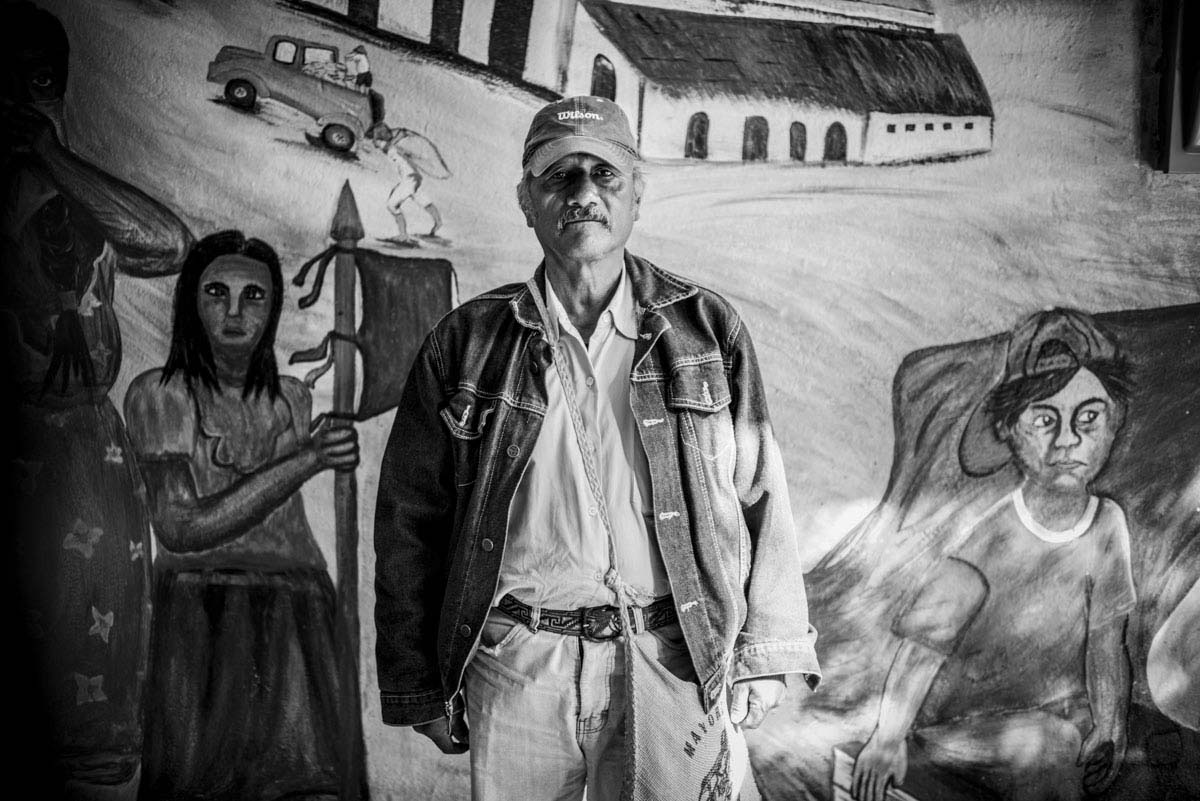

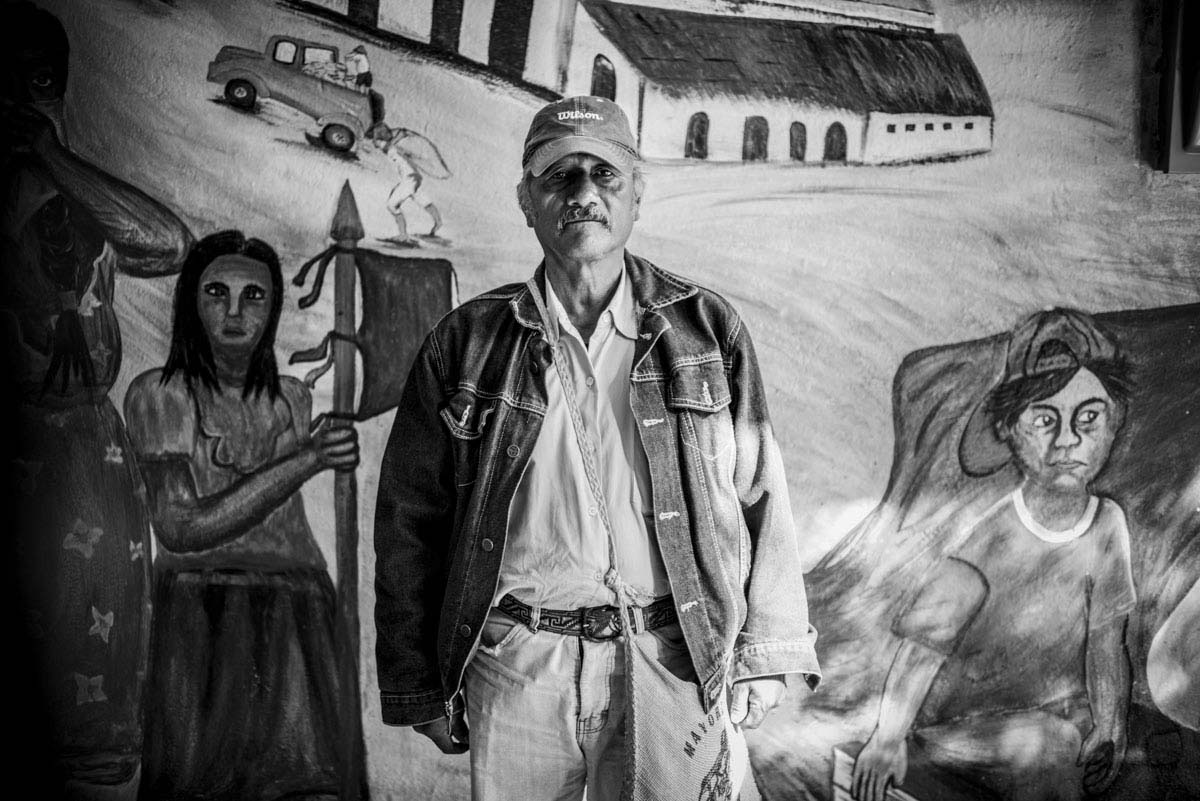

Liste first visited the victims’ families. “I knew they were key in understanding the pain that so many Mexican families have been facing for so long,” he says. “All of the families were staying at that Ayotzinapa university where their kids were before they ‘were disappeared’.”

Some parents were sleeping in the same beds that used to be occupied by their children, the photographer tells TIME. “I stayed at the university during el Dia de Muertos, the country’s most important national holiday. Lots of students from all over the country were arriving to support these families and show their respects for the victims.”

Liste spoke with these families for hours as they waited for answers. “[At that time], the government had failed to provide clear information about what had happened that night,” which, he says, used to be an accepted part of life in Mexico – until that night.

“Parents all around the country started to say, ‘Enough’. “ The words “Vivos se los llevaron, vivos los queremos” [“They were taken alive, alive we want them back”] became a national anthem. “That night, the relationship between these [corrupt officials] and drug cartels was [made more evident] than ever before, and Mexican society is tired of the deaths and the disappearances. One thing is sure, it will now be difficult for them to silence an entire country.”

Sebastian Liste is represented by Noor Images. See more of his work here.

Photo essay edited by Alice Gabriner, TIME’s International Photo Editor, and Mikko Takkunen, Associate Photo Editor at TIME.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com