The story of Queen Victoria is surprisingly and deeply intertwined with the birth of photography as a medium. In an exhibition opening at The Getty Museum in Los Angeles on Feb. 4, curator Anne Lyden has organized a comprehensive look at Victoria’s relationship to and influence on photography, from her first encounters with it as a young woman to her seminal Diamond Jubilee portrait. Victoria grasped from a young age what it would take the rest of the world many years to realize: that photography could be both an artistic medium as well as a mechanism of propaganda.

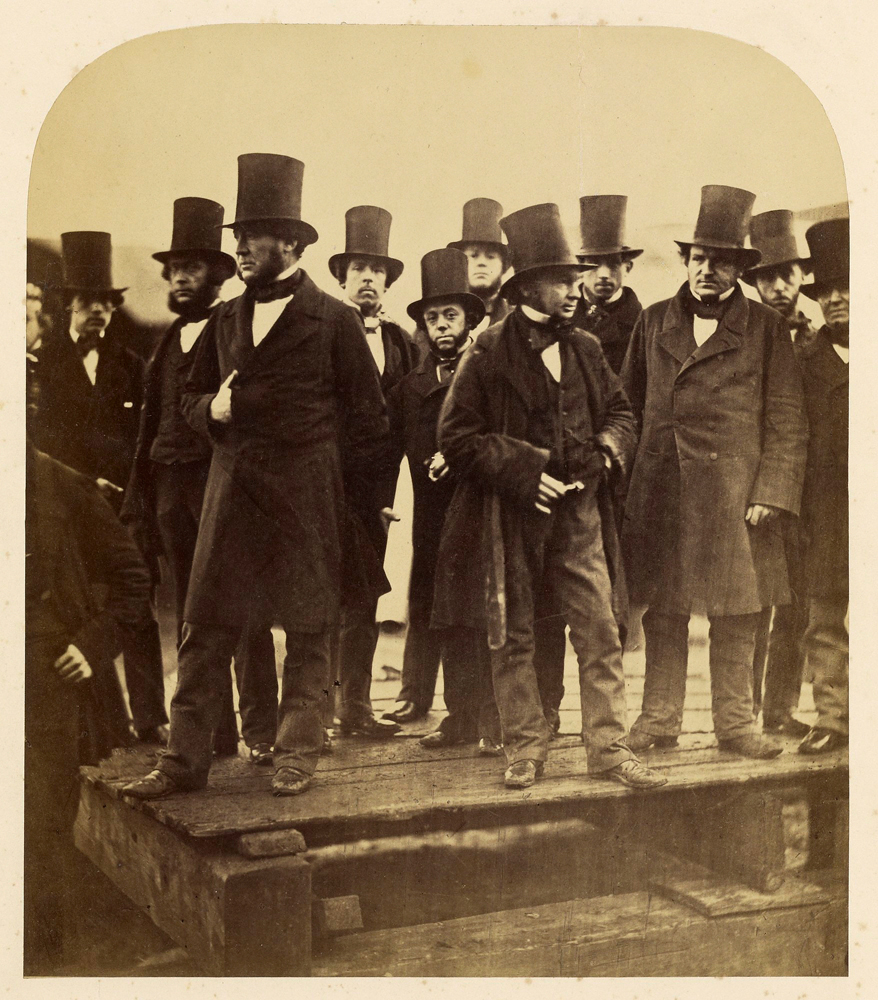

In 1840, at the age of 20, Victoria married Prince Albert, who was himself an ardent supporter of new technologies. The young Queen and prince became vocal patrons and two of the earliest, highest profile adopters of the medium, from learning the process of making daguerrotypes themselves in a specially built royal dark room to collecting some of the earliest examples of photography in the forms of daguerrotypes, calotypes, and glass plates. The couple began to commission portraits of the royal family and surveys of the grounds, giving work to local photographers such as Roger Fenton who would later cover The Crimean War at the request of the Queen. Victoria and Albert publicly announced their patronage of the Photographic Society of London and made it a point to attend photography exhibits, including, famously, the Great Exhibition in 1851. Their enthusiasm for photography undoubtedly influenced its early growth and the public’s reception of the medium.

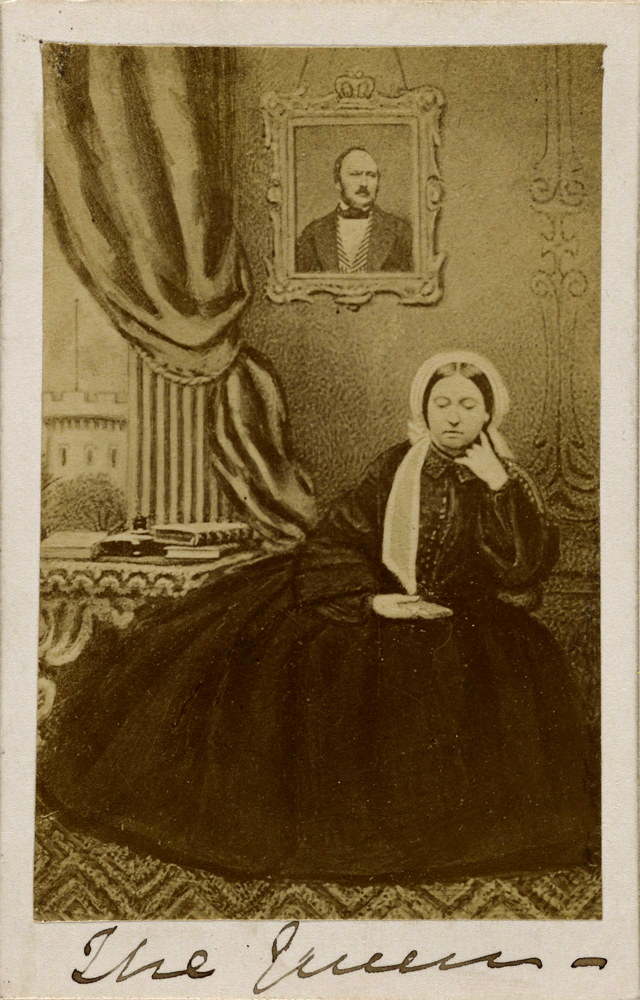

Through the exhibit, Lyden concisely tracks the development of Victoria’s understanding and deployment of photography. In an early portrait of the Queen and her children taken in 1852 (above), Victoria found the rendering of the children’s faces acceptable, but her own likeness was “horrid.” She disliked the portrait so much that she scratched out her face on the negative. She was much more calculated in subsequent portraits, aware of the position of her body and the expression on her face. While Prince Albert was alive, she used photography to pay tribute to their famously passionate love for one another, often commissioning portraits where she would hold or be looking at photographs of him: she seemed to understand early on the power and layered meaning of making a photograph of a photograph. When Albert died suddenly at the age of 42 in 1861, Victoria expressed her mourning in portraits where she would be shown in black with pictures of Albert hung on the wall behind her or framed on a table beside her.

In her later years, Victoria’s use of photography became increasingly calculated and strategic. Her now famous Diamond Jubilee portrait (slide 9) was released in 1897, but was taken several years earlier by W. & D. Downey at a wedding. Knowing that copyright restrictions would limit the circulation and usage of the photograph, Victoria convinced the photographers to give up their rights to the image ahead of its publication. It appeared on everything from tea towels to biscuit tins, and became the most lasting image of her. It is why, as Lyden says, when we think of Victoria we think of these last few years of her life, not of the younger self. This was very much the queen’s own doing.

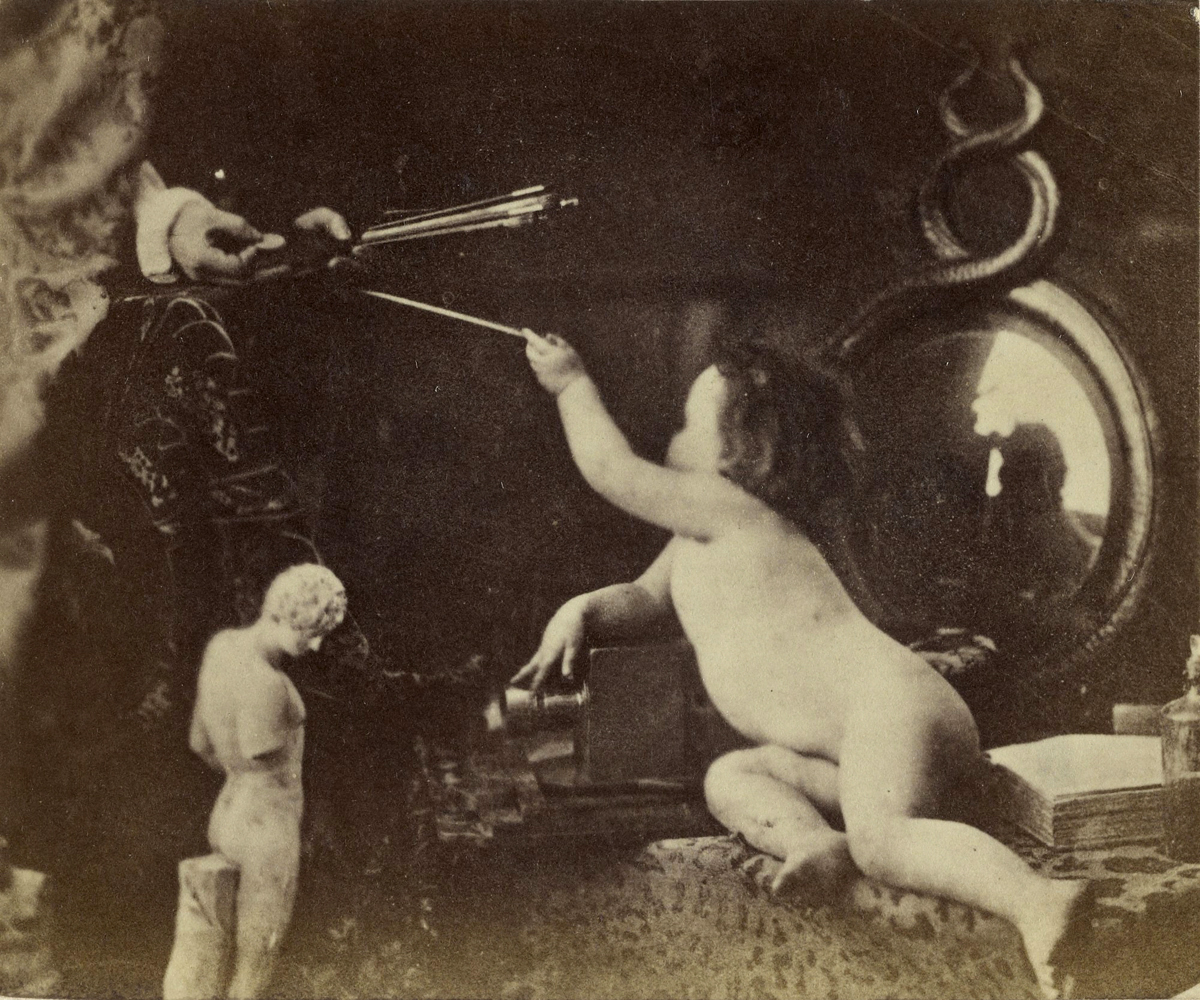

Victoria’s private passion for photography grew and matured throughout her lifetime. Both before and after Albert’s death she continued to add to the royal collection, purchasing photographs by such renowned and influential early photographers as Oscar Rejlander, William Henry Fox Talbot, Gustave Le Grey, and Julia Margaret Cameron. She established a now-common practice of commissioning and distributing royal portraits, shaping the public’s view of the royal family. At her death, Victoria left a note detailing the objects that were to be buried with her in her coffin. They included, among other items, jewelry, a plaster cast of Prince Albert’s left hand, her lace wedding veil, and photographs.

A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography is on view at The Getty Museum in Los Angeles, Feb. 4 – June 8, 2014.

Mia Tramz is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter @miatramz.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com