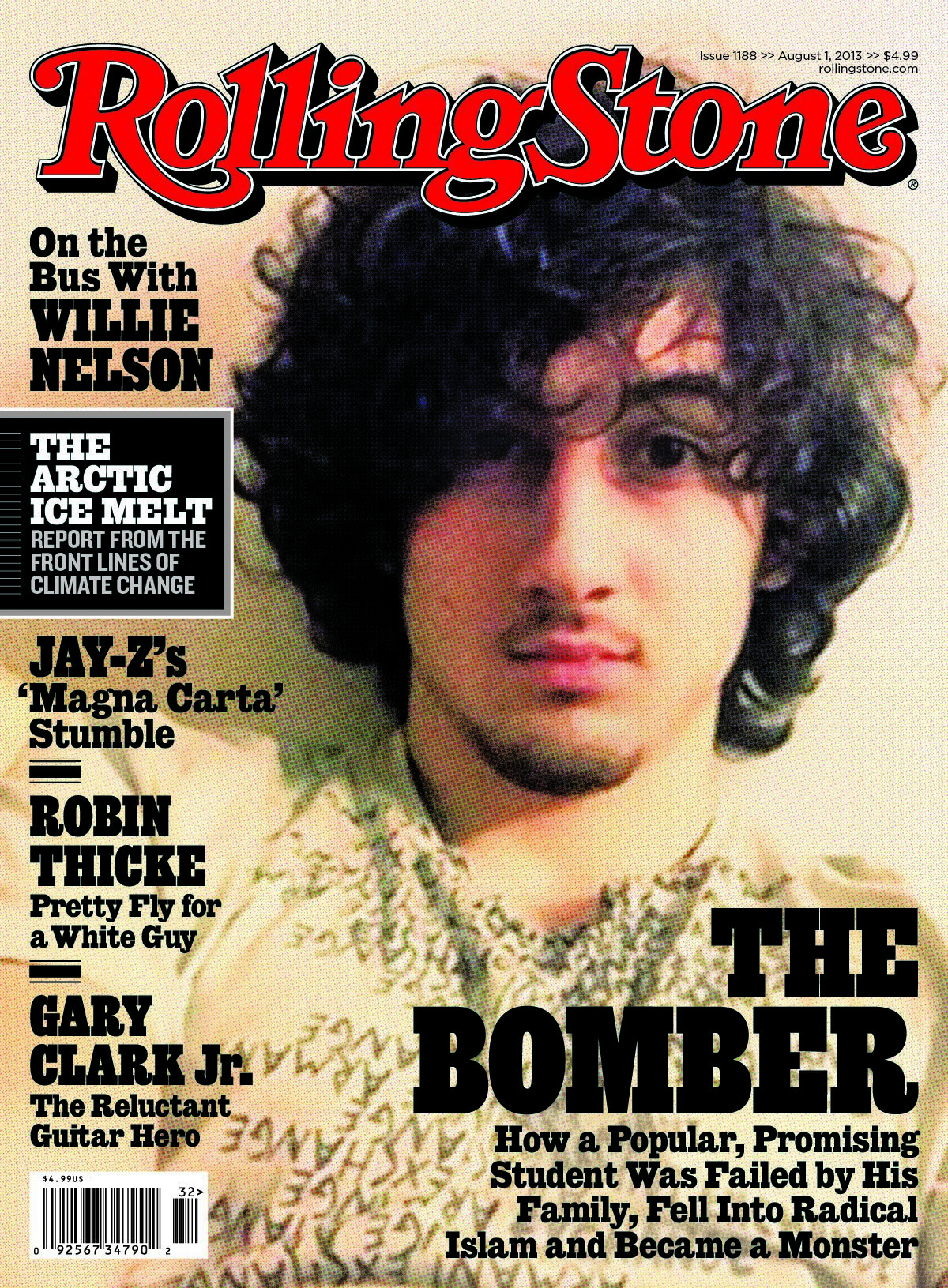

The headline is stark, even lurid: “The Bomber: How a Popular, Promising Student Was Failed by His Family, Fell Into Radical Islam and Became a Monster.” The concept of “innocent until proven guilty” aside — being identified as “the bomber” and then called a “monster” on the cover of a national magazine won’t help in finding impartial jurors — the words themselves are not the cause of so much anger among so many people.

The image of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on Rolling Stone’s cover is under attack because it is widely perceived as glorifying the 19-year-old and, by implication, the horrific deeds of which he stands accused. Sergeant Sean Murphy, a Massachusetts policeman, independently released his own photos of the search for and capture of Tsarnaev because he was so offended by the picture on the magazine’s cover: “The truth is that glamorizing the face of terror is not just insulting to the family members of those killed in the line of duty,” he told Boston Magazine, “it also could be an incentive to those who may be unstable to do something to get their face on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine.” And he goes on, referring to the import of his own pictures, including one of Tsarnaev bloodied with a luminous sniper’s dot on his forehead: “This guy is evil. This is the real Boston bomber. Not someone fluffed and buffed for the cover of Rolling Stone magazine.” As a result of his unilateral actions, Murphy was suspended from the force.

In an age of image wars and relentless “branding,” a popular notion is that the side controlling the imagery wins the war. Photographers were largely eliminated from the first Persian Gulf War to diminish the possibility that their imagery might adversely affect the morale of the citizenry back home, as had happened during the Vietnam War; during the second Persian Gulf War photographers had to be embedded with the military, with limited ability to publish certain kinds of graphic images. (Even photos of flag-draped coffins returning to American soil were banned for a number of years). And when Osama bin Laden was finally killed after enormous effort, pictures of his death were never shown. As President Obama put it at the time, “It is important to make sure that very graphic photos of somebody who was shot in the head are not floating around as an incitement to additional violence or as a propaganda tool.”

Terrorists, too, are engaged with the image war, attempting to control the ways in which they are depicted, at times also opting to remain invisible—as initially happened during the September 11 attacks when even their affiliations were unclear, as well as during the 1972 Munich Massacre. In Munich, Black Septemberterrorists wore masks to conceal their identities during their lethal attack on Israeli athletes and coaches during the Olympic Games. In the age of the image, the absence of a human face can foment even more terror.

But in the case of Tsarnaev we are looking at a photograph that he is said to have made of himself, a “selfie” published on a social media site. It resembles many of the countless images made by adolescents as they self-represent online, trying on various identities for a larger world that they are expected to engage with via the Internet. The photograph, when not onRolling Stone’s cover, seems to show a somewhat hesitant teenager not all that sure of himself. The lighting in the picture appears somewhat flat, yellowish, and shadowed, while Tsarnaev himself looks a bit pallid, and seems to be leaning away from the camera. When the New York Times put the photograph on its own front page with the headline, “The Dark Side, Carefully Masked: Bombing Suspect Hid a Troubled Second Life,” rather than feeling heroic, it seemed to corroborate the idea that there was something about him requiring another look. And the photograph did not provoke complaints.

Images, of course, take on new meanings depending upon the contexts in which they are displayed. In the case of Rolling Stone, placing its red logo over the bombing suspect’s hair can read like an endorsement, especially now that the photograph has been cropped to make him seem both more important and assertive, and the lighting on his face is rendered with greater nuance. A more skeptical approach would have been to inset the photograph of Tsarnaev without the magazine’s logo running across it so that the image reads more like a Facebook photo or a mug shot of a suspect. (Andy Cowles, a former Rolling Stone art director, shows how this might have been accomplished in his excellent dissection of the graphic issues, “Why the picture’s not the problem,” at coverthink.com.)

By contrast, when 1994 Los Angeles Police Department mug shots of O. J. Simpson upon his arrest appeared on the covers of Newsweek and Time, respectively headlined “Trail of Blood” and “An American Tragedy,” his skin digitally darkened, his face blurred, and a spotlit glare added via the use of image software for the latter, it would have been exceedingly difficult to think of Simpson as being glamorized.

Many have compared Tsarnaev’s image on Rolling Stone to previous covers of rock stars like Jim Morrison, or to the magazine’s 1970 cover feature on Charles Manson (“The incredible story of the most dangerous man alive”). But there is a deeper and more resonant resemblance, one that all too frequently emerges with the repetitive use of certain kinds of iconic images. Given the rich tradition of representational imagery in Christianity, as well as the often unconscious cultural biases of tastemakers in the West, it’s hardly surprising that images reminiscent of depictions of Jesus predominate, even when those portrayed are from other cultures. In the Rolling Stone instance, removing the magazine’s logo from his hair not only helps nullify a perceived endorsement of him (and perhaps of his actions), but it crucially also does away with a red appendage that can be viewed as resembling a bloodied Christ’s crown of thorns. Given the religious aspect of the accused’s alleged motivations, the cover image provocatively alludes to Tsarnaev as another who suffers, perhaps even legitimately, for a larger cause.

As photographs, those made by Sean Murphy of Tsarnaev are not more “real” than the one that Tsarnaev made of himself; all of the images have much to say, but none tell a complete truth. (Those published within the magazine add other perspectives, as well.) Intentionally or not, Rolling Stone hit an already inflamed nerve with the way it used this one particular photograph on its cover. A prominent headline reading something like “Story of a Troubled Teenager,” accompanied by a flatter image without the magazine’s logo going through his hair, might have persuaded many to consider empathizing with Tsarnaev. And if the magazine’s editors had been able to publish a cropped version of Sean Murphy’s photograph of a bloodied young man emerging from a boat with a sniper’s red dot on his forehead, that too might have attracted enormous criticism for glamorizing Tsarnaev, this time as a possible victim and rebellious outlaw.

Villains, of course, do not always look the part. We would be both naive and irresponsible if we continued to expect them to meet our expectations of what “bad guys” should look like. Surrounded by billions of images, a more helpful approach would be for all of us to deepen our visual literacy in order to read photographs and videos with greater subtlety. We should also consider more complex visual strategies to depict the people and events around us. Otherwise, we will remain trapped in repetitive image wars,

mired in very real pain and anger, while the battles that demand our attention remain largely outside the frame.

Fred Ritchin is a professor at NYU and co-director of the Photography & Human Rights program at the Tisch School of the Arts. His newest book, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, was published by Aperture in 2013.

Ritchin previously wrote for LightBox about a photograph’s inherent meaning and power.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com