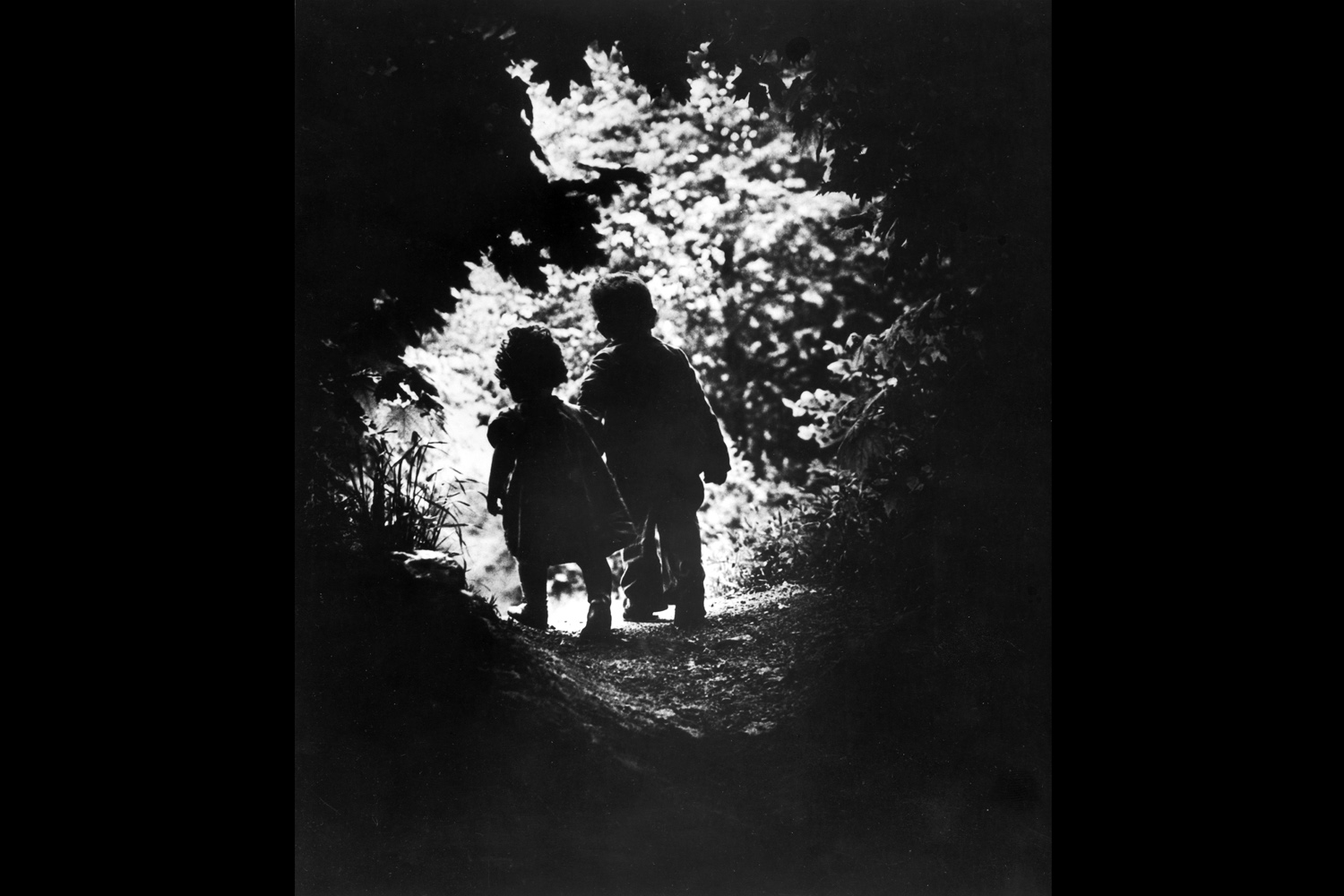

In 1955, a decade into the Cold War, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened its doors to a monumental photography exhibition, an aesthetic manifesto visualizing ideas of peace and “the essential oneness of mankind.” Edward Steichen, then director of the MoMA photography department, curated 503 photographs — from a pool of two million — by 273 artists from 68 countries with the at-once simple and grand goal of definitively “explaining man to man.”

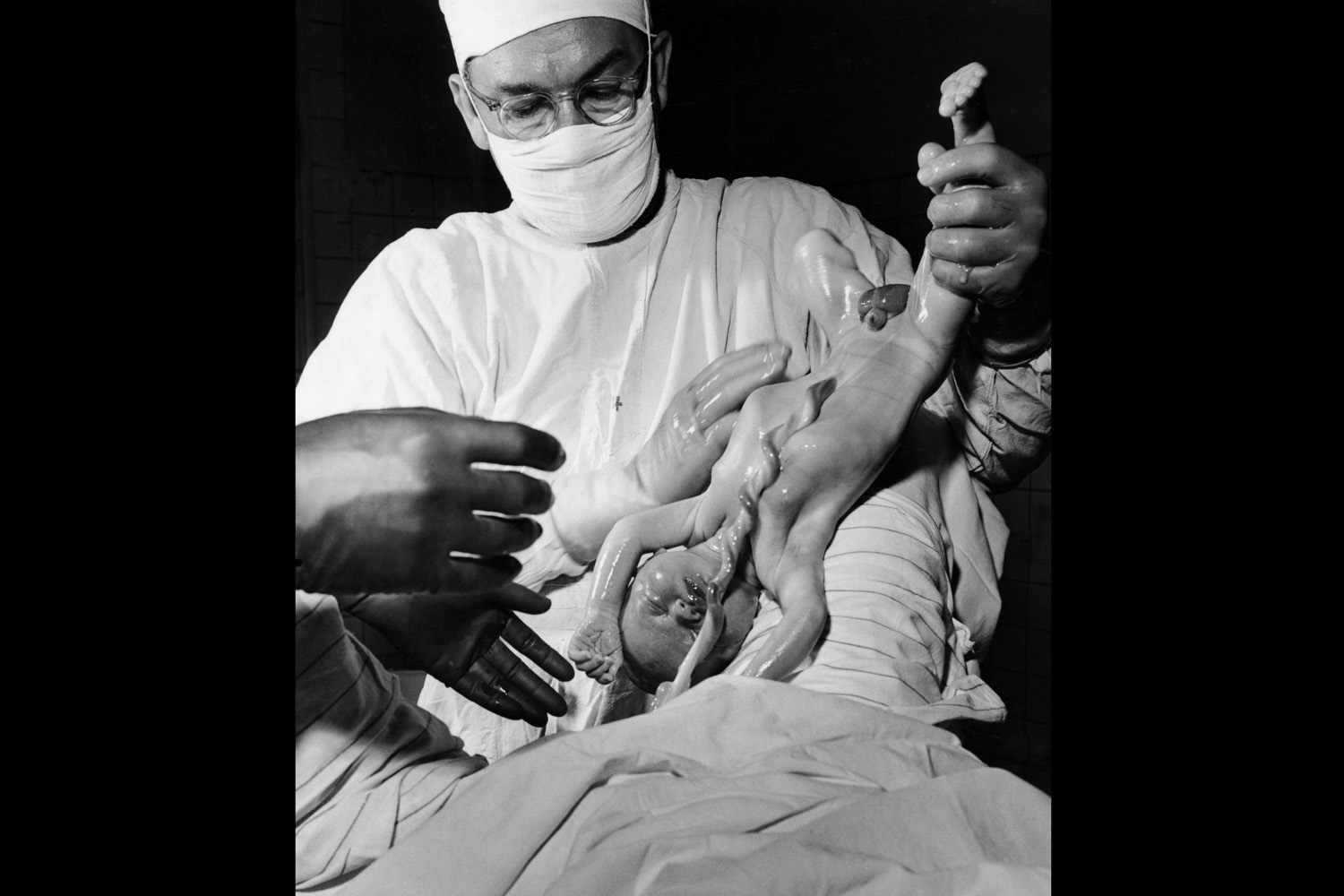

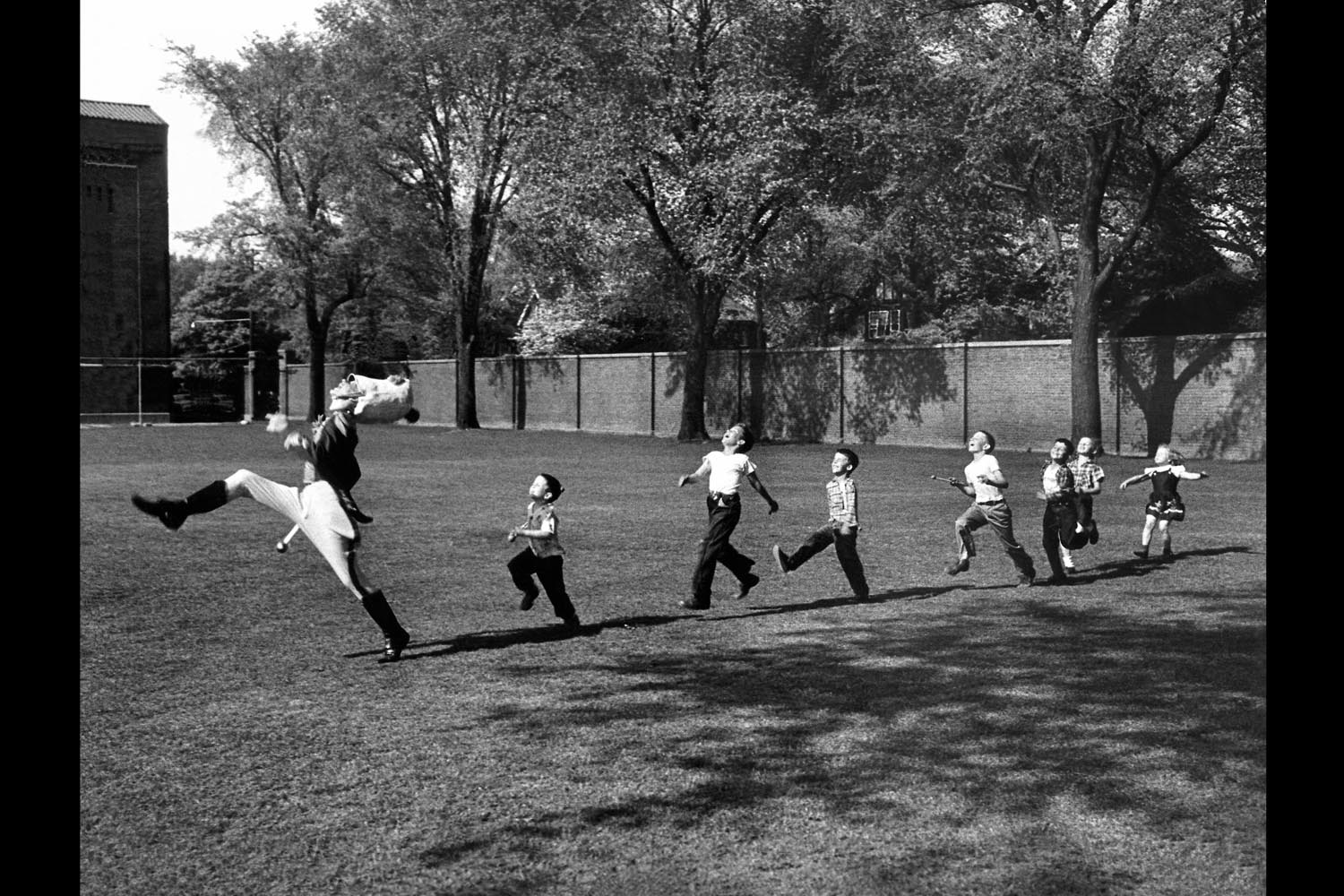

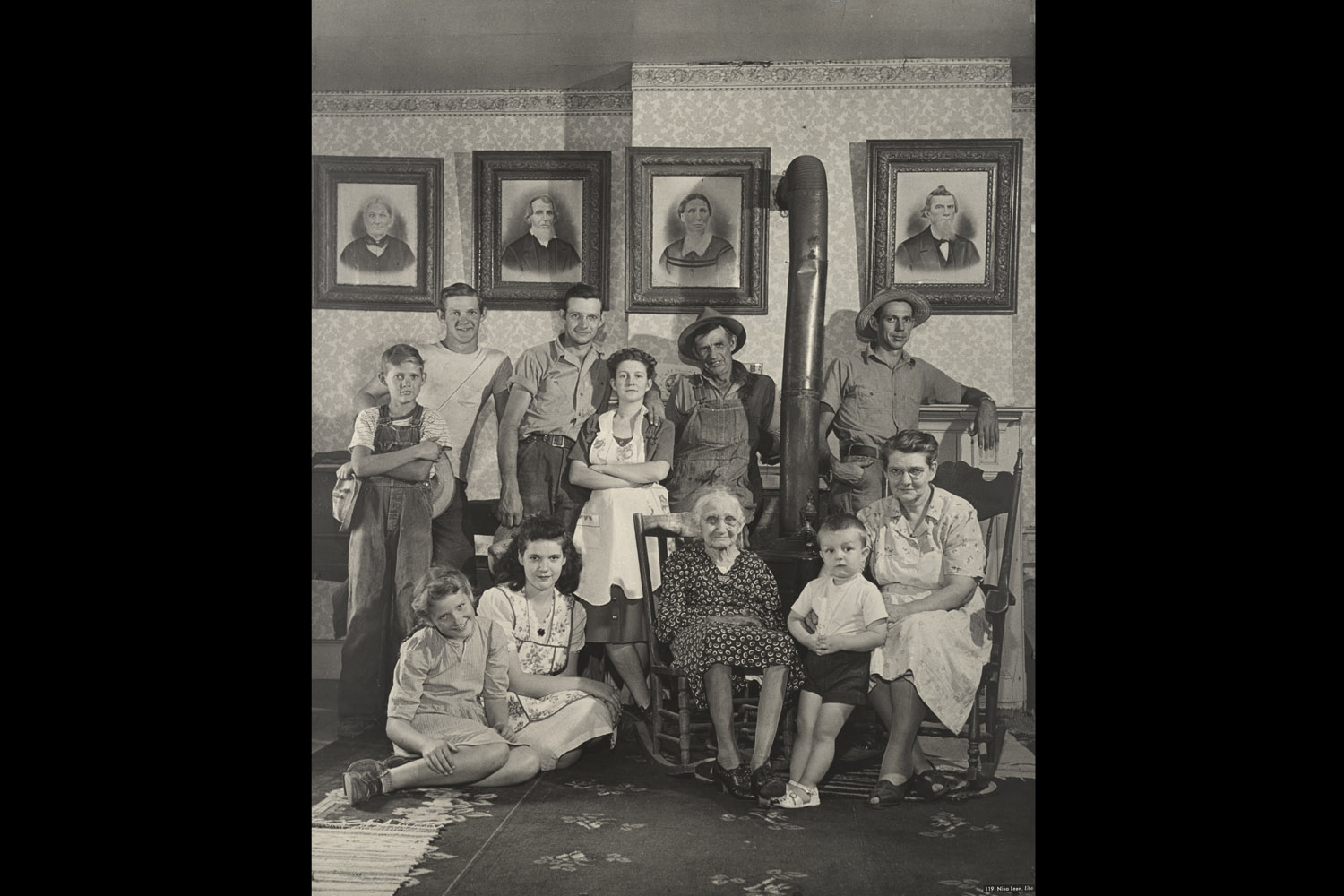

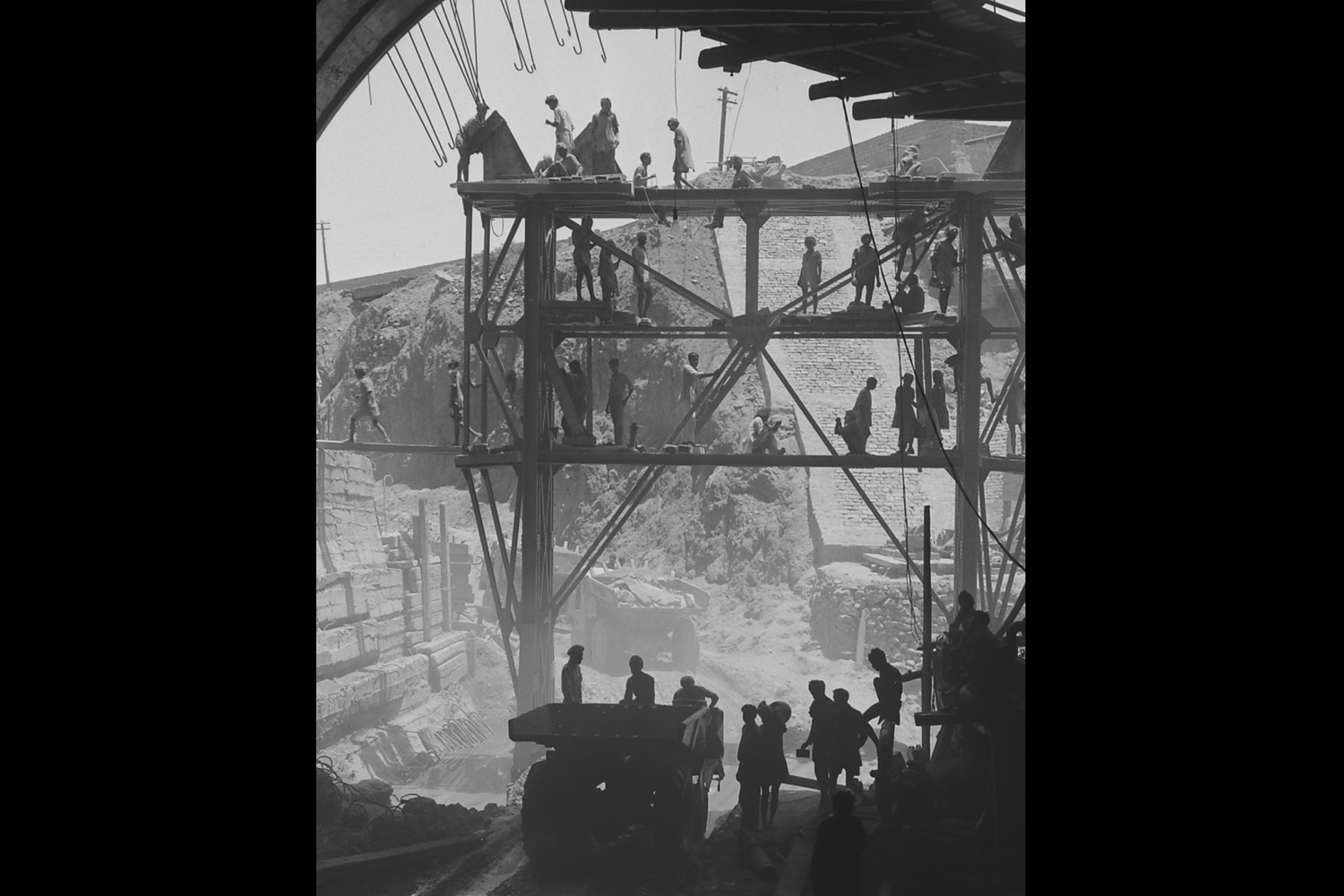

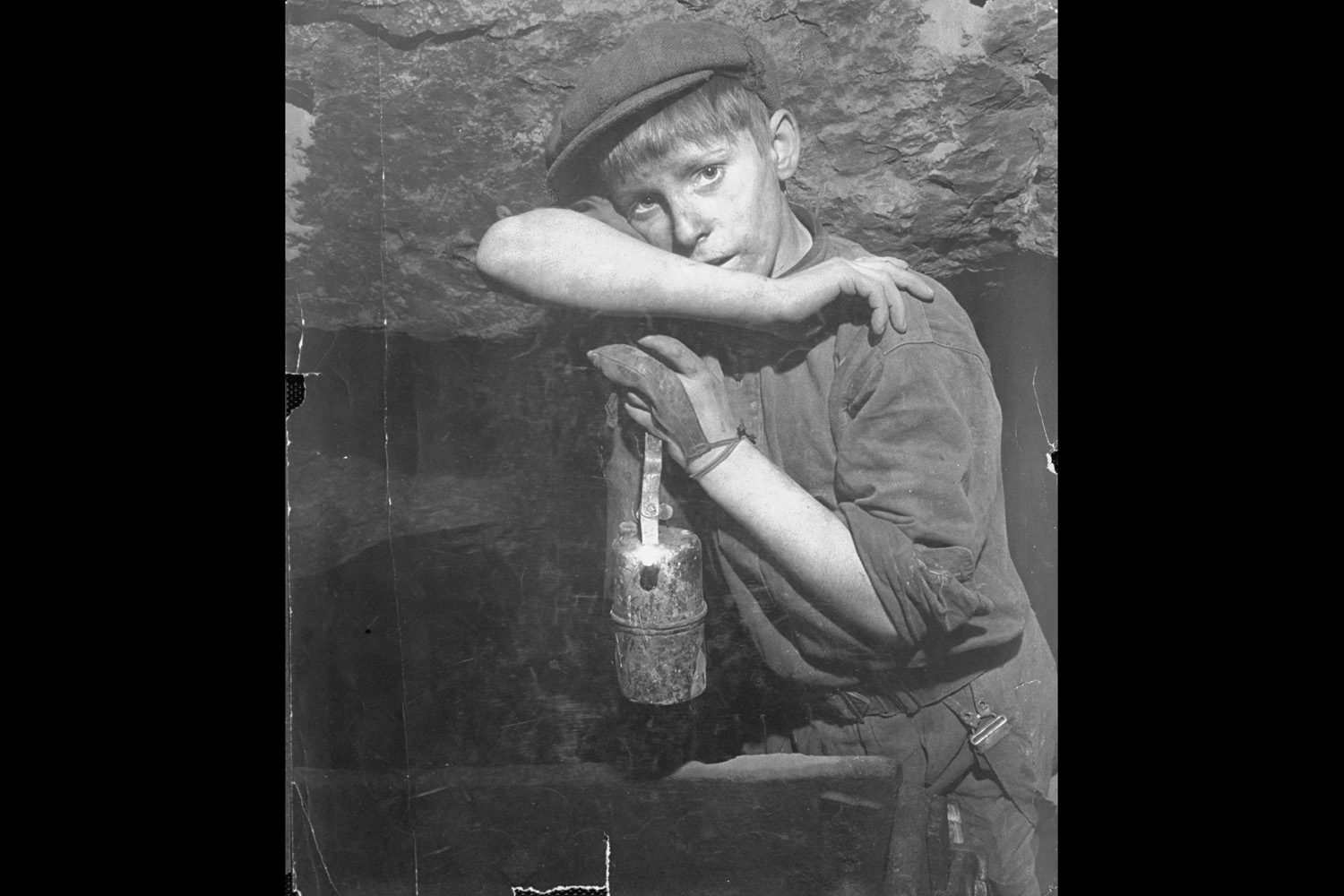

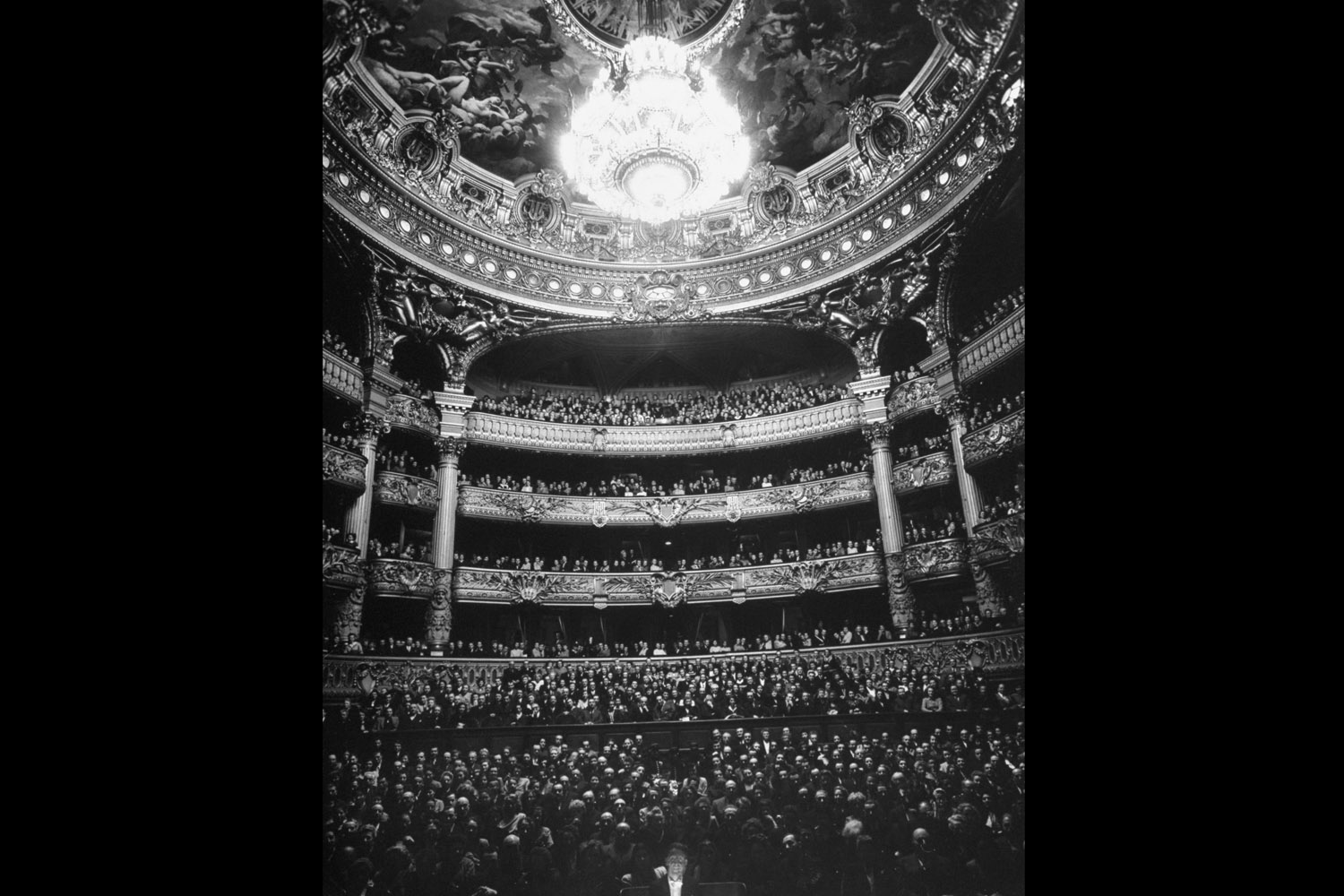

Steichen called The Family of Man the most significant work of his career, writing later in the exhibition catalog — which has since sold millions of copies — that it was the “most ambitions and challenging project photography has ever attempted.” An immersive installation of monochrome prints glued onto wood frames upwards of 13 feet in length and often suspended from the ceiling, the exhibition was grouped by themes thought common across all cultures: birth, love, labor, joy, and others. The roster of photographers contained many names that remain in obscurity, but many more that have gone on to achieve legendary status: from Elliott Erwitt and W. Eugene Smith to Alfred Eisenstaedt and Nina Leen.

The exhibition has since become one of the most celebrated in photography history, touring more than 150 museums worldwide and quietly thrilling more than 10 million visitors. Now, after a three-year process of cleaning and retouching, the exhibition’s well-worn prints — scratched, many with broken corners, some peeling from their frames — have been masterfully restored to their original condition. This month, the entire exhibition opened to the public anew at its permanent home at Clervaux Castle, a 900-year-old national monument in Luxembourg, Steichen’s birthplace.

The markings of the project’s long and well-traveled life have been covered up, while the new exhibition space has been renovated to replicate the visitor experience of the original MoMA show. The collection itself, meanwhile, feels like a relic — significant, and memorable, but a relic nonetheless — of the past. The all-encompassing inclusiveness of its original intent, after all, grows less authoritative with each passing day, as more and more cameras come into the hands of more and more underrepresented members of the increasingly diverse human family.

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com