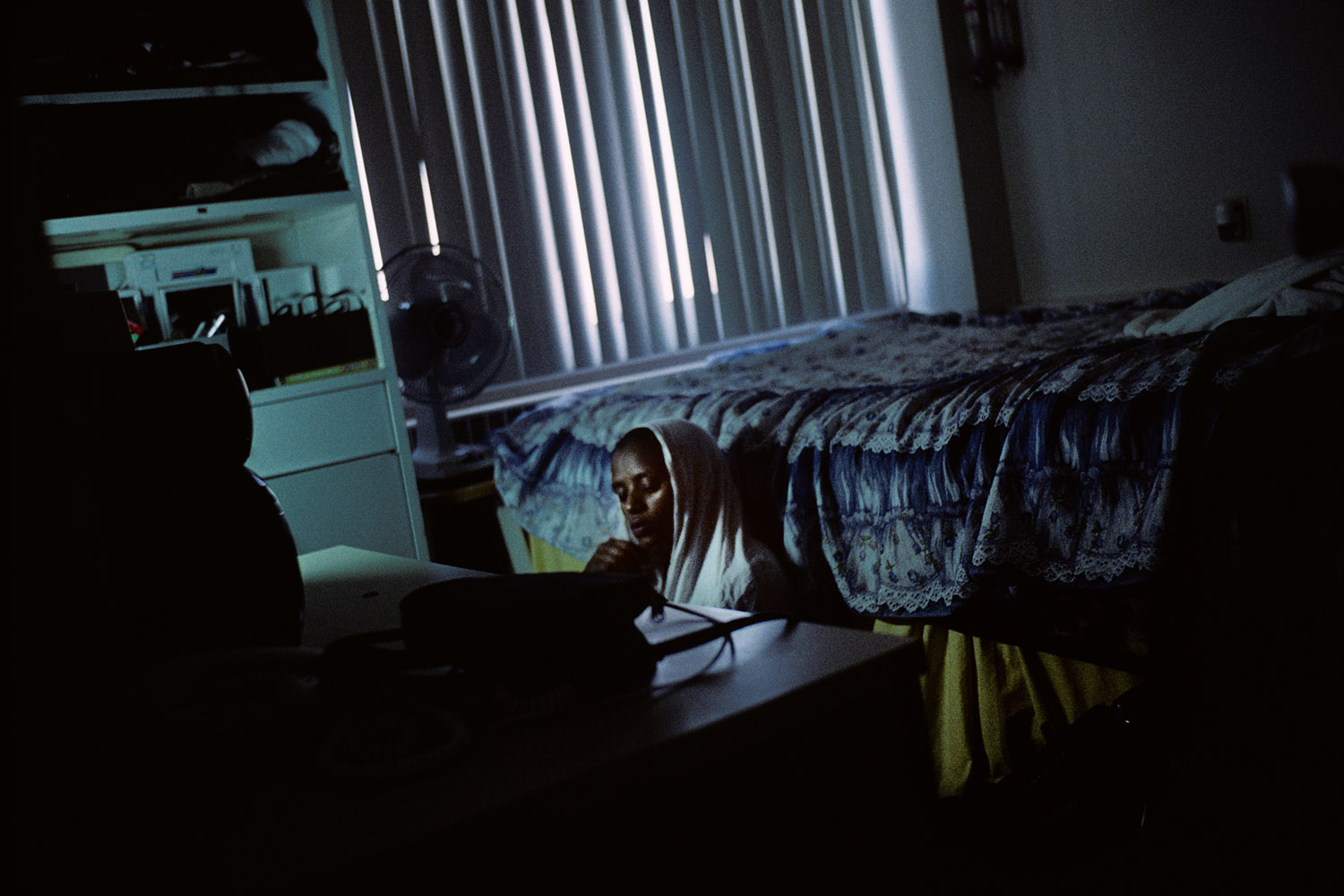

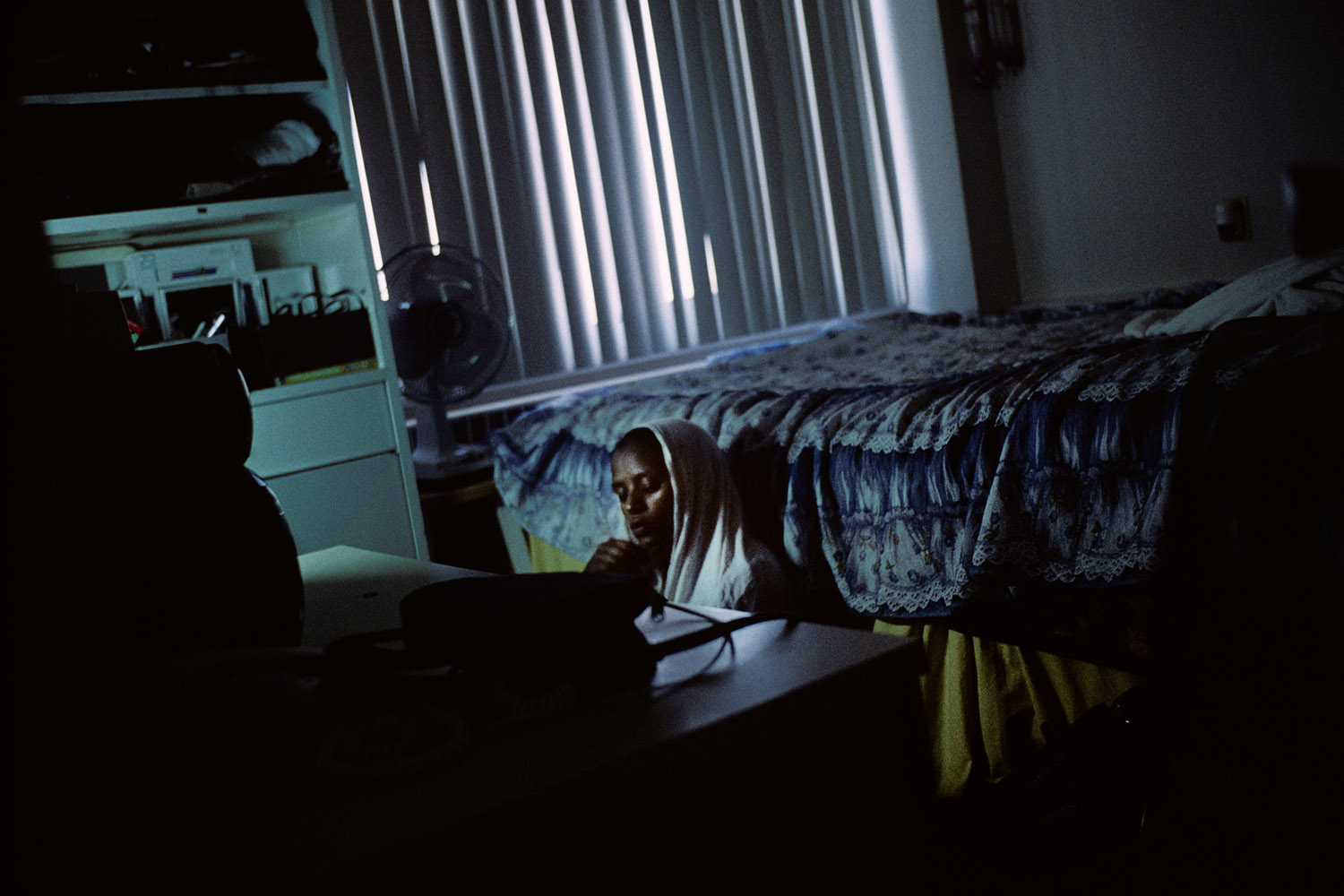

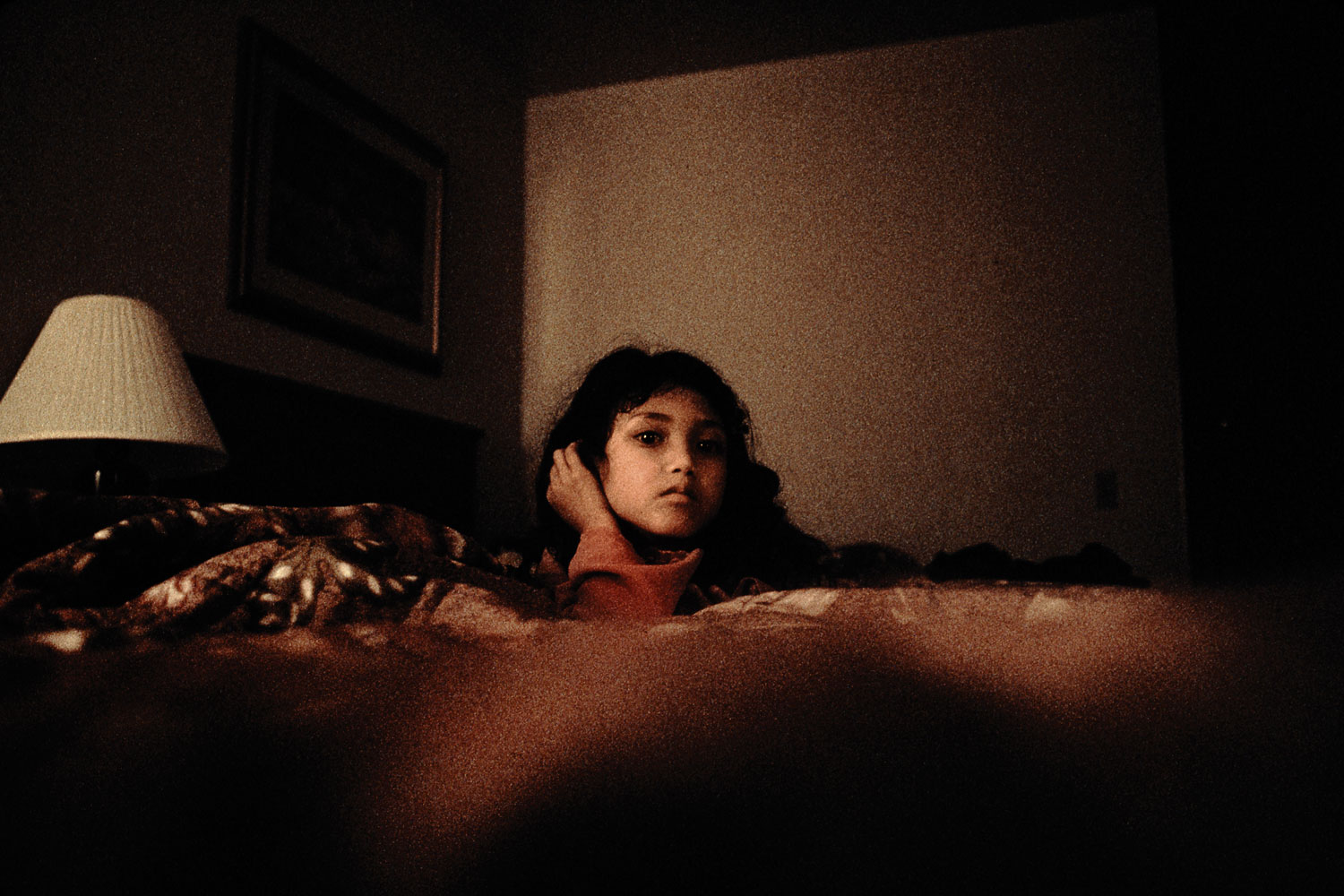

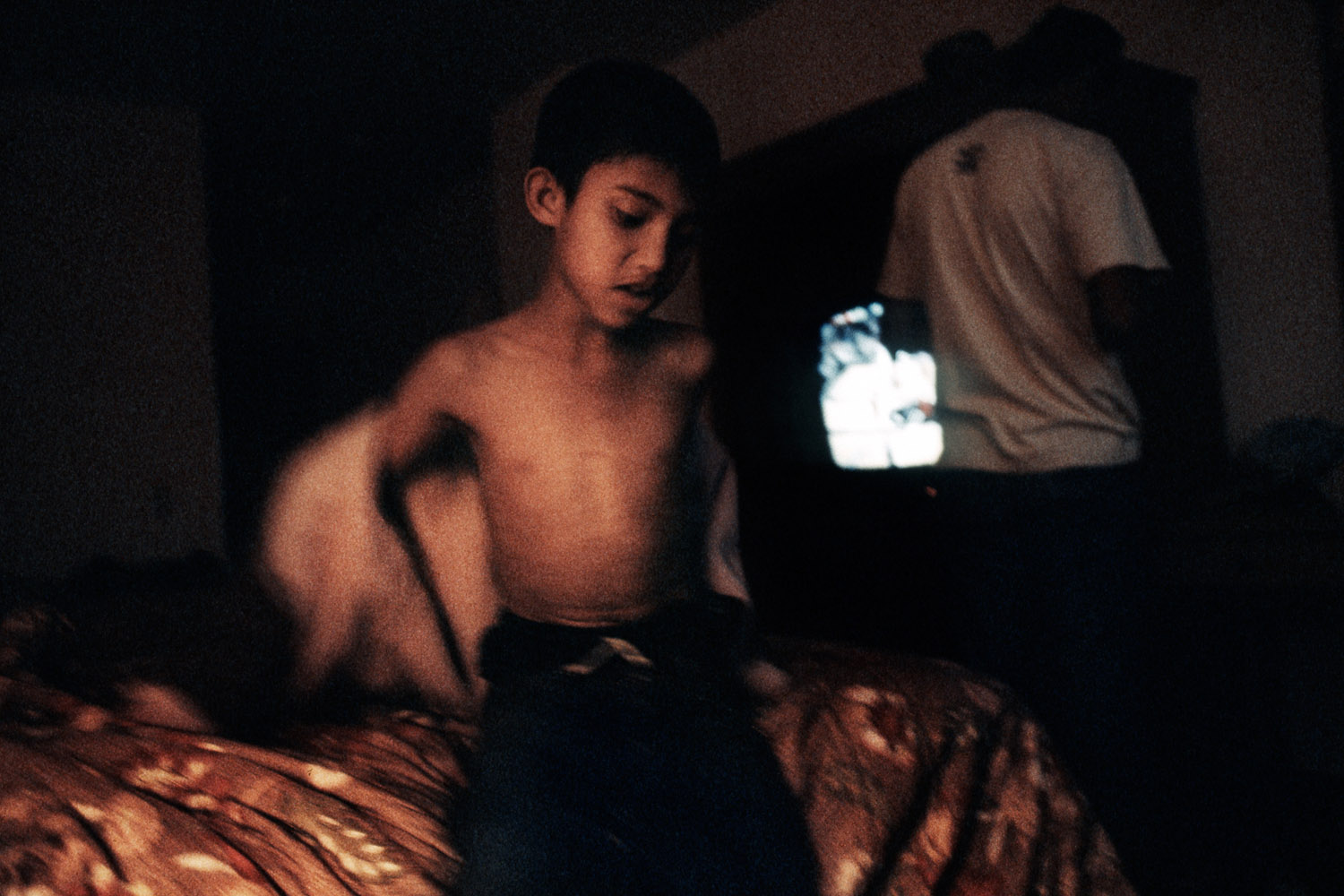

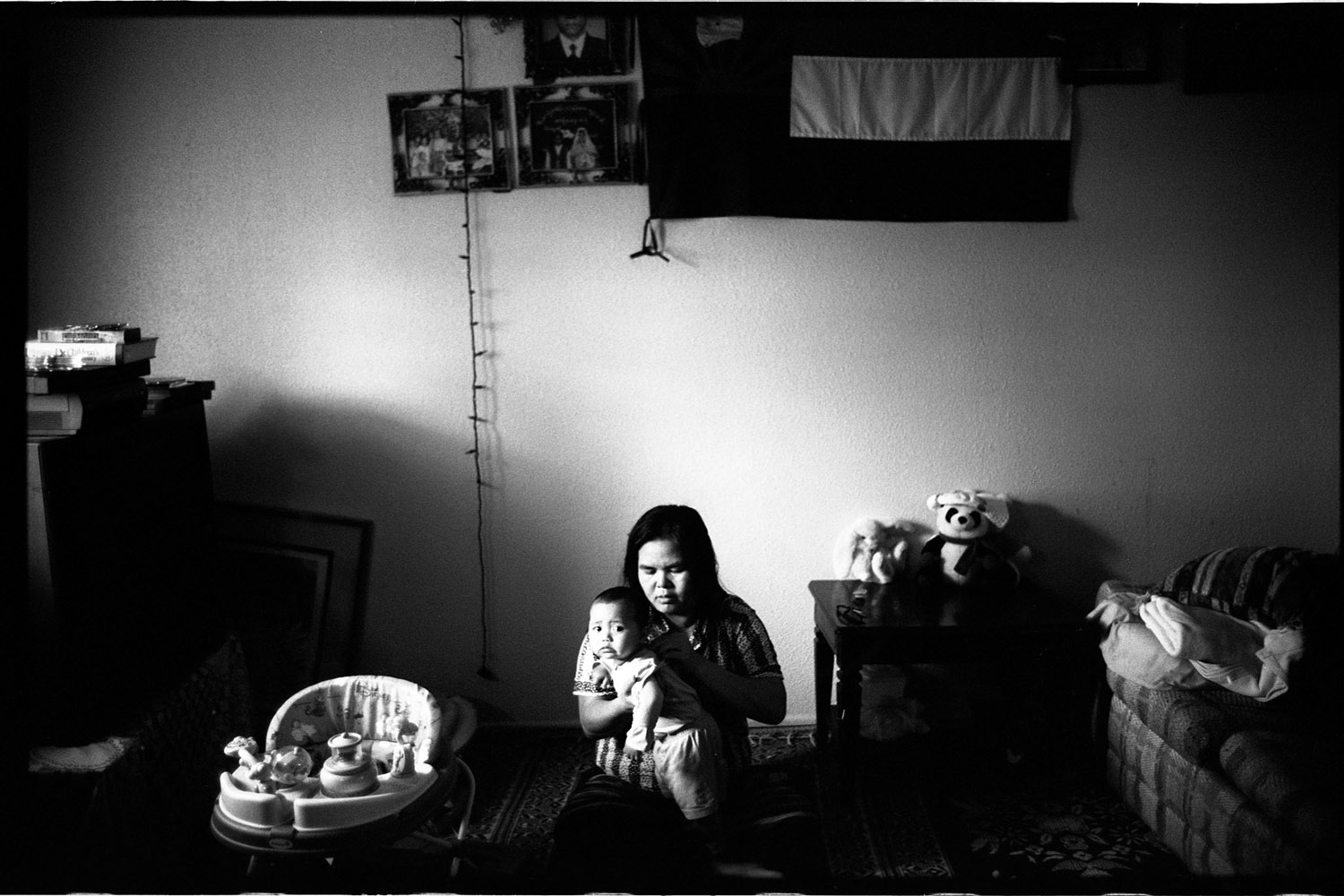

Bewildered, exhausted, displaced and lost in their own thoughts, the subjects in Gabriele Stabile’s photographs have traveled far and suffered greatly. Newly arrived refugees in the United States, they spend their first night in America in the temporary shelter of an airport hotel. Many of them endure torturous delays in their native lands—often waiting years in makeshift camps before finally gaining entry to America and an opportunity to build a new life. Once on American soil, these refugees from war, famine, religious persecution and every other imaginable human-made and natural calamity will spend a single night — 10 to 12 hours — at the hotel before they continue their journey, settling in far-flung destinations across the 50 states. Ukrainians to California, Africans to Fargo — the decisions made by the resettlement agencies are often based on existing communities that can offer support and aid in the acclimation of the new arrivals.

The Italian-born Stabile, now based in New York, covered five airports of entry for his project — Newark, JFK, Miami, Chicago’s O’Hare and Los Angeles International — and concentrated on documenting the immediate experiences of the new arrivals to a new world.

“I found myself focused on the gateway from their past,” Stabile says. “I used to say they live between uncertainties. One is their past, which they had to abandon, and the other is their future, because they don’t know what is going on, what will happen in America, or what it is going to be like.”

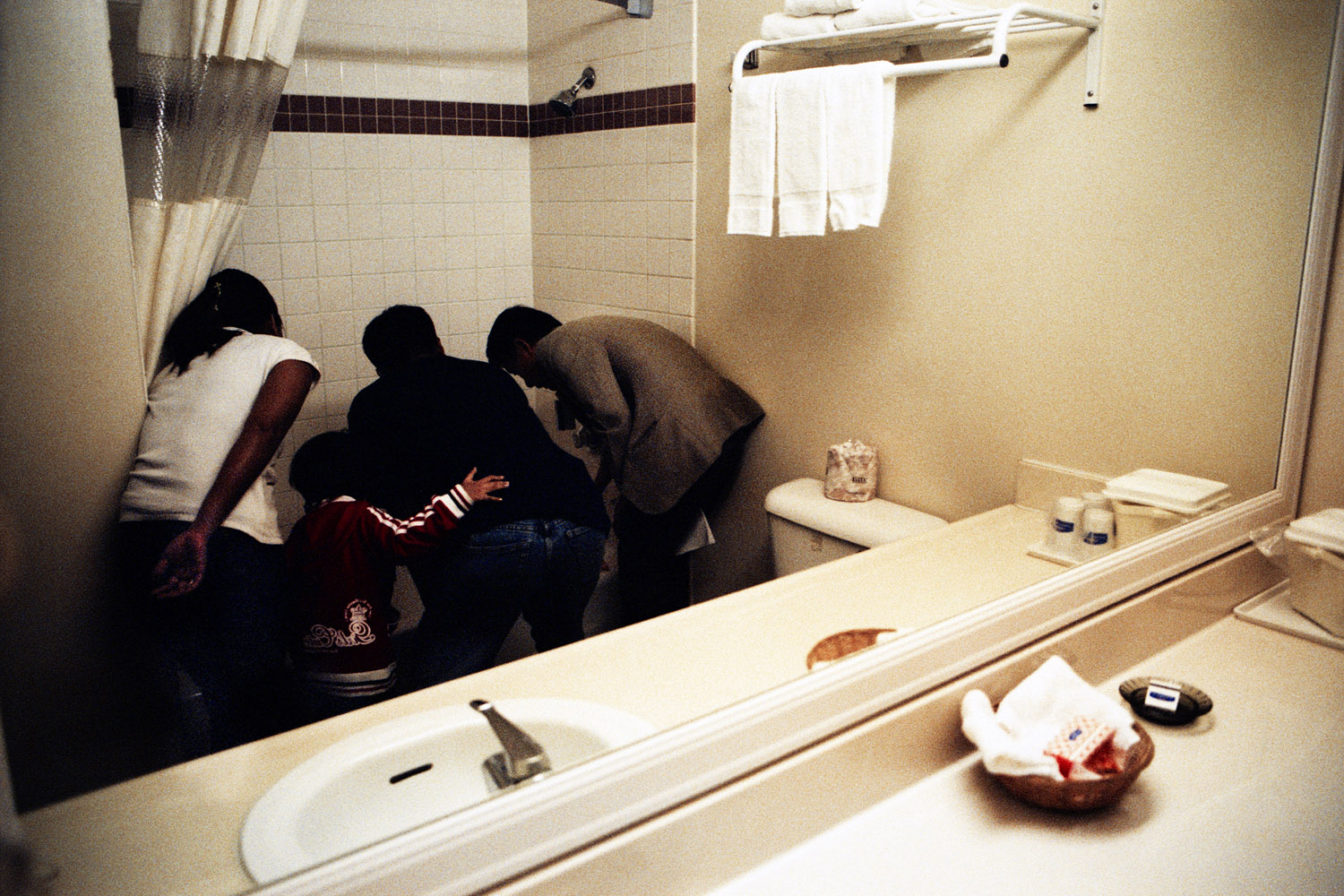

“It’s a suspended reality,” Stabile explains, “where you have to suspend your belief, too. You see an African family of ten people spending all night in the hallways of the hotel and refusing to get into their own rooms to sleep because they’re afraid that the officials are going to forget them — forget about them and leave them there.”

Stabile finds the situations close to “unphotographable.” Arriving in the dead of night, bathed in darkness, the refugees arrive at hotels with generic, fireproof furniture and ugly, flowery wallpaper — a surreal environment for a traumatized traveler to face.

These conditions aid, rather than disrupt, Stabile’s appropriately dark, atmospheric aesthetic. His layered compositions (and reflections) often convey the refugees’ disorientation. In other photographs, isolated refugees seem to emerge from the shadows of their unfamiliar surroundings, physically and mentally displaced and lost in their own thoughts. The mix of emotions and sense of shock are almost palpable.

Stabile and his subjects, meanwhile, appear to have understood one another through his camera. “I was hiding a bit behind it and they were kind enough not to [hide from it]. Some of the people didn’t want to be photographed but mostly they were open.”

He connected with the refugees not only through the lens but through simple acts of kindness, like lending his cell phone so they could call their loved ones and friends back home to let them know they had safely arrived.

As the refugees continued their journeys to their resettlement communities, Stabile maintained contact, becoming friends with some and receiving random calls from others.

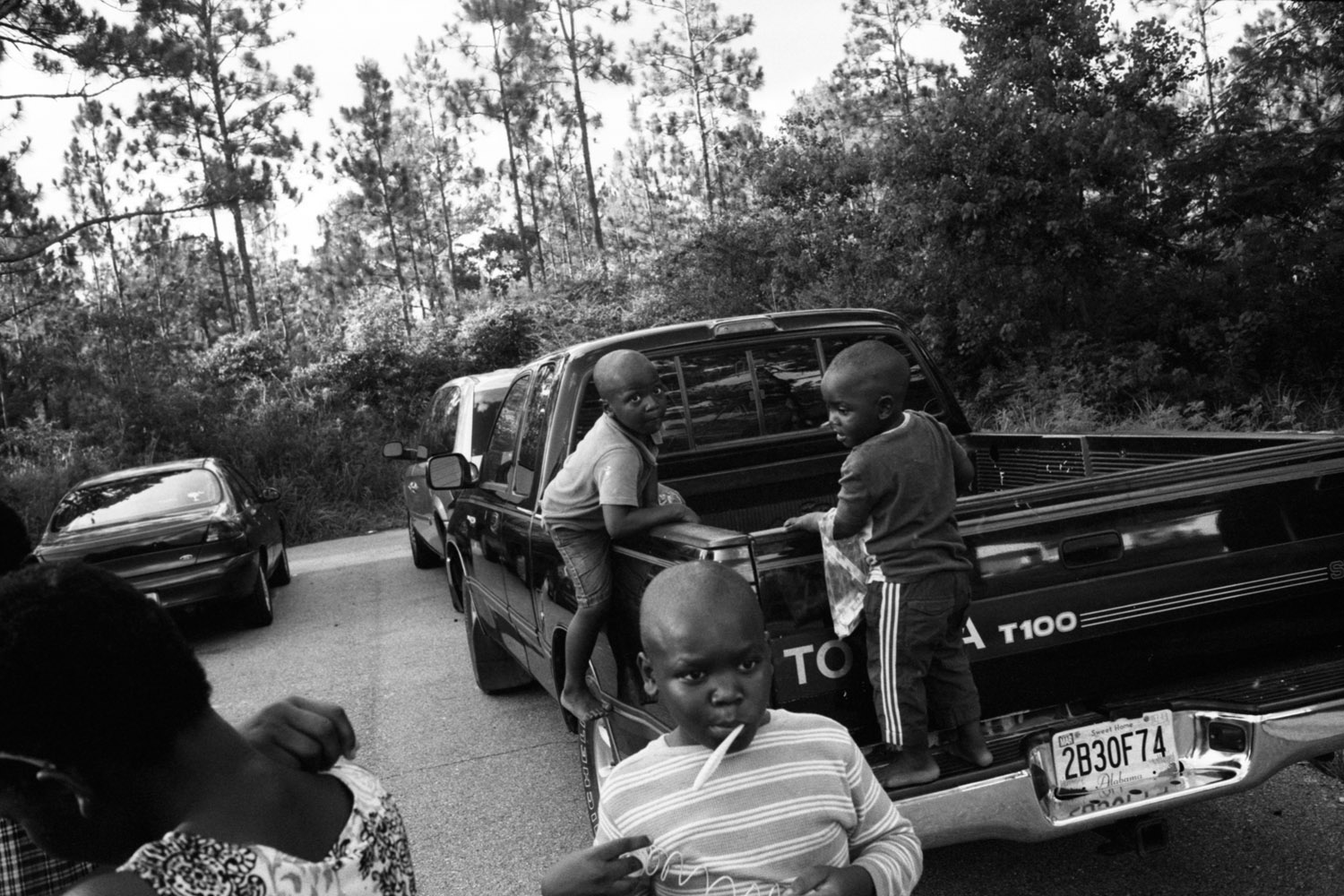

“There’s a family in Mobile, Alabama. Every year, on the anniversary of their arrival, they call me,” Stabile says, “because I was the first western guy to show interest in their story and lent them my phone. They remembered that as an act of kindness. The guy wants me to talk to his seven daughters and wife and we don’t even speak the same language!”

A letter from a young refugee named Samira, meanwhile, struck Stabile deeply enough to alter the course, and expand the scope, of his entire project. After meeting her upon her arrival in Newark, he had photographed Samira and her family in Minneapolis — a location he visited that was not a port of entry, but rather a destination for refugees. After he had largely lost touch with the family, Samira wrote Stabile a letter that he characterizes as “very tough, accusing me of disappearing from their lives after [initially] showing interest.”

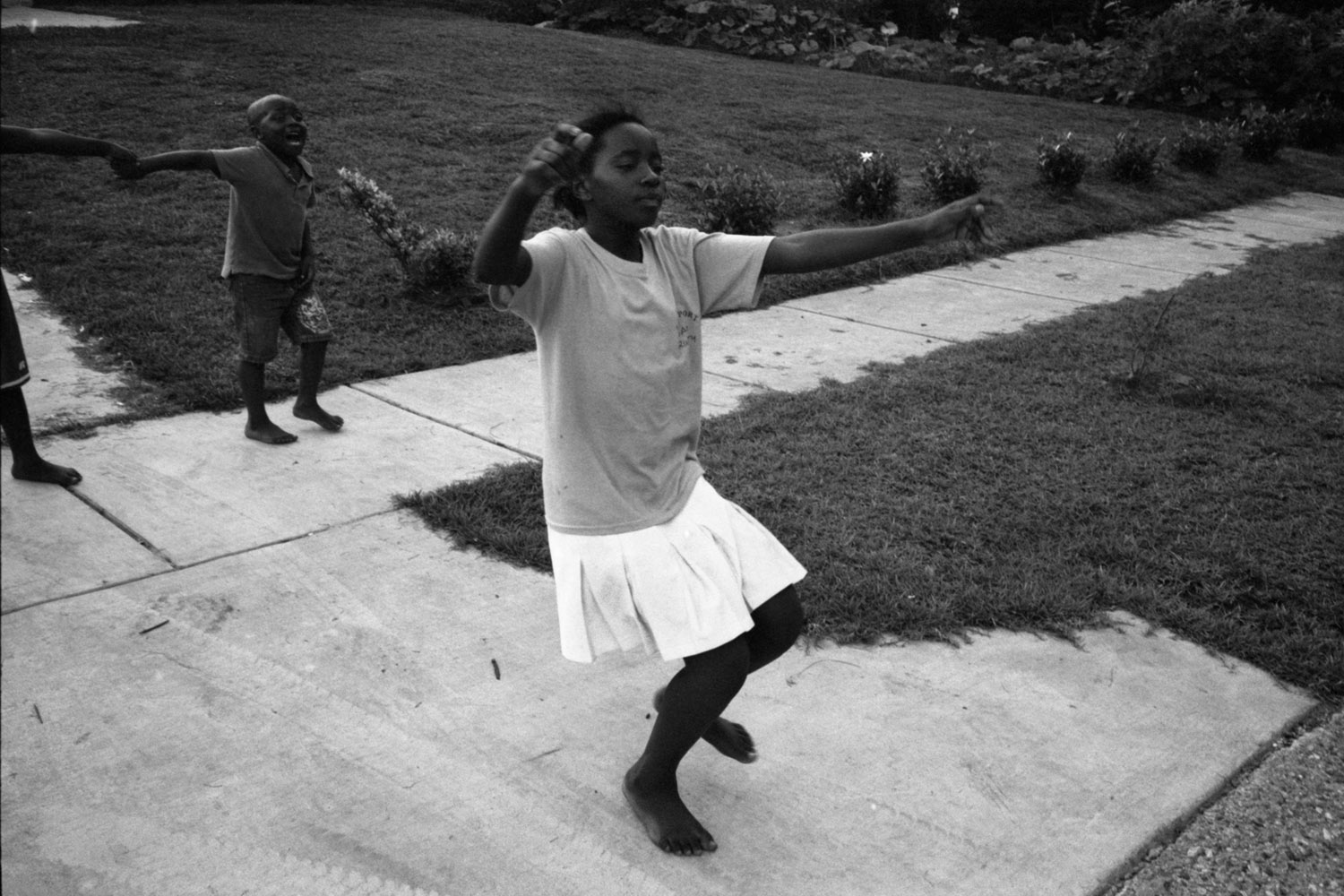

This recognition finally led Stabile to expand the refugee project to tackle the larger and, in many ways, far more emotionally fraught story of resettlement — how refugees affect the America is which they now live, and how America has affected (and continues to affect) them. This journey, his journey, is something that, Stabile says, all photographers eventually end up shooting: getting lost in America.

Stabile’s Refugee Hotel is the first photo book published by Voices of Witness. The book is structured into three distinct chapters — two photographic and one written. The first is an impressionistic documentation of the refugees’ first night in the hotel. The second chapter, written by co-author Juliette Linderman, is a series of first-hand accounts and oral histories. The testimonies are stark and full of yearning to rebuild lives beset by adversity and delayed by circumstance and bureaucracy. The third chapter focuses on their resettlement to the smaller communities of America.

The photographic bodies of work are separated by four years and aesthetically are two distinct entities. The first was mostly shot in color Kodachrome and the second with black and white film. The sections were shot during two different periods of Stabile’s own life, between 2007 and 2012 — the first as a young photographer recently arrived in the U.S. and the second as a permanent resident and father of two.

The project represents a serious amount of investigative journalism, with organizations like the International Rescue Committee (IRC) providing tremendous help in tracking down the refugees.

In the second half of the project, Stablile concentrated on the smaller towns the refugees were dispersed to — towns that weren’t as ethnically diverse as the larger metropolitan areas the refugees first arrived in. The second chapter accentuates the paradox of American culture and reinforces the surreal nature of their first nights here.

“The actuality is that there are African people living in Fargo, North Dakota — lost in the fog of an environment in which all you see after a while are roads and strip malls and little towns. These people are trying — scrambling — to make it work in that environment, which is totally and unbelievably different from what they’re ready to approach,” Stabile says.

Many of these resettlement programs are successful. There’s a road map to becoming an American, and it’s an intricate plot. But it does work, especially with young refugees, because they are able to adjust more easily.

Stabile notes: “We live in a very controlled environment in which you’re supposed to take steps to improve — get a better job, put together your retirement money, send your kids to college and have a nice car, for example. That’s what America is about. Not only do many of the refugees not share these values — some even find them offensive. Change is a big undertaking for people who are in their forties and fifties. So they hang onto their beliefs, their ways of doing things.”

Although some share in the ideal of the American dream, others Stabile visited in Mobile, Alabama, for example, were practicing polygamy in the accepted tradition of their culture — a tradition where it is not only recommended to have more than one wife, but where it’s permissible to buy and sell women.

But this is not always what it seems.

“One man waited all night until his wife returned from a trip from Dallas. He was crying because he was finally united with his wife after maybe three days. So they meet and hold each others’ hands and start praying to God that they were actually together again. And this is a guy who bought this woman from a farmer next door. You realize that these are structures we impose on ourselves — of the way our society works. What matters is what you feel, how you relate to your environment and to the people that surround you — but if you think about it, this is happening under the radar in Alabama. Are these guys actually Americans now? They’ve lived here five years.”

“Some of them have these two voices in them. For example, they want their customs to survive, you know, moving to America — they’re afraid they’re going to lose their identities by losing their ways. They are farmers who will never farm again, architects that will never design another building. They find themselves cleaning restrooms at the country club, doing maintenance jobs or working as car mechanics.”

“One thing that I think was common to all of these ethnicities, to all of these experiences, all of these stories, was that misery, once you experience it, never really goes away. You carry it with you.”

Gabriele Stabile is an Italian photographed based in New York. Refugee Hotel, published by Voice of Witness, is his first book.

Voice of Witness is a non-profit organization that uses oral history to illuminate contemporary human rights crises in the U.S. and around the world. Founded by author Dave Eggers and physician/human rights scholar Lola Vollen, Voice of Witness publishes a book series that depicts human rights injustices through the stories of the men and women who experience them.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com