War/Photography, on view from Nov. 11 to Feb. 3, is a magnificent, wide-ranging exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. As chief curator Anne Wilkes Tucker explains in the sumptuous catalogue, that slash in the title is important: this is not a show simply of photographs of war. It’s a demonstration and examination of the relationship between the two and how that relationship has changed over time. There are plenty of images of combat, but the catchment area extends way beyond the battlefield–both in space and in time–to include preparations for war, refugees fleeing its consequences, damage to property and the physical and psychological aftermath of conflict. Taken by some of the most famous photographers—more than 280 are showcased—in the history of the medium, by aerial reconnaissance units and unknown combatants and civilians, the pictures are drawn from the archives of photo agencies such as Magnum, military archives and personal family albums. It’s a stunning show, full of well-known pictures, surprising new ones and—if one consults the catalogue—surprises about well-known pictures.

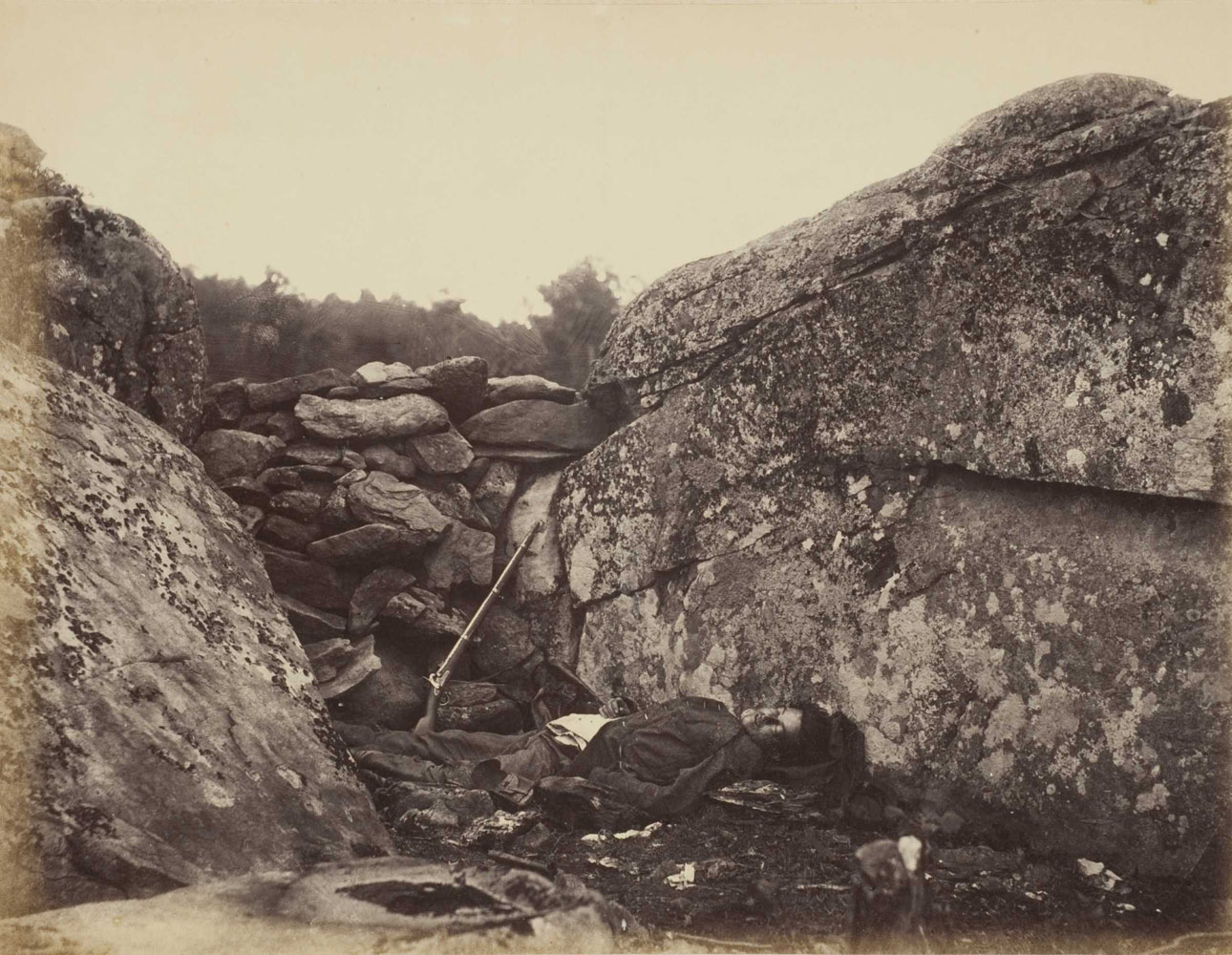

More than a few of the featured pictures have been either faked or staged. That is to put it too simply, for the slipperiness of the distinction between “real” and “arranged”, or “genuine” and “fake”, turns out to be one of the themes of the show. The problem crops up right from the get-go, with Roger Fenton’s famous pair of pictures of the Valley of Death (1856) from the Crimean war—one of which shows cannonballs strewn more abundantly than the other. (slide #1) The scholarly war over which picture was taken first continues to rage. I thought this question had been definitively settled by Errol Morris in his book Believing is Seeing but John Stauffer argues in the catalogue for precisely the opposite conclusion. The “Dead Rebel Sharp Shooter” in Alexander Gardner’s famous image from the Civil War (slide #2) was dragged to the place where he is seen to have died and arranged in such a way that the rifle — not his own but a prop carried by the photographer — added extra pathos.

As with the Civil War, so in the First World War: it was impossible to take pictures of actual combat. One of the reasons why the famous footage of soldiers going over the top at the Battle of the Somme is faked is because it is on film. Filmed at a training ground, it shows a soldier who is shot, falls down, looks at the camera — and folds his arm before dying. Among the most spectacular images of the war, James Frank Hurley’s “An Episode after the Battle of Zonnebeke” (c.1918) (slide #3) seems like a composite expression of our idea of the Western Front — because, it turns out, it is a composite print made from multiple negatives. As Siegfried Sassoon wrote in his poem “Cinema Hero”: “It’s the truth/That somehow never happened.”

The complexity of Hurley’s image is in stark contrast to Wesley David Archer’s photograph of a pilot who has bailed out of his burning plane (c.1933) (slide #4). It is a picture full of suspense because we don’t know whether the parachute is going to open. What we do now know, courtesy of his widow, is that it was done with a model airplane. Armed with this knowledge you go back to the original and… it still looks amazing! You don’t feel cheated so much as admiring of someone who could create such a truth after (or independent of ) the fact.

Everyone is familiar with the doubts that continue to swirl around Robert Capa’s picture of the “Death of a Loyalist Militiaman” (1936) (slide #5) in the Spanish Civil War. No one can agree on exactly the circumstances in which it was made. And so, ironically, while photography is generally assumed to be strong as evidence but weak in meaning, Capa’s photograph has come to resemble painting, of which the contrary is held to be true. Joe Rosenthal’s image of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima in 1945 is an especially complicated case in that it was widely assumed to have been staged, faked, rigged or something like that, even if we can’t remember exactly what is supposed to have gone on because it’s all a bit muddled up with memories of the Clint Eastwood film about what happened.

The full story, as narrated in the catalogue, is that the flag was raised twice — not for Rosenthal’s benefit but, in the words of the Lieutenant Colonel who ordered it to be done, “so that every son-of-a-bitch on this whole cruddy island (could) see it.” (slide #6) How do we know this is accurate? Because there are photographs – i.e. photographs of the sequence of events that led to Rosenthal taking his photograph – to prove it. (see below) In any case, the success of Rosenthal’s image was due to the way that it not only recorded a moment and event but, in doing so, expressed a truth of enduring – even mythic – proportions about the Marine Corps. The same could be said of Len Chetwyn’s iconic picture from the North Africa (1942) campaign: a photograph which proves, at the most basic level, that this was indeed a battle waged by men in shorts! (not shown). The fact that a detail from it is used on the cover of a beautiful Australian edition of Alan Moorhead’s African Trilogy highlights the way that documentary veracity and imaginative truth are mutually supporting. The surprising thing – which turns out not to be so surprising if we consider how perfectly the picture is composed and lit — is that it’s the photograph that provides the imaginative half of that equation. Smoke grenades had indeed been deployed, but for pictorial effect rather than combat effectiveness.

So there is a delicious irony, in a show that is so scrupulous and judicious in its investigation of the relationship between real and doctored pictures that the catalogue seems, in one instance, to have fallen victim to a booby-trap in its midst. John Filo’s photograph of the killings at Kent State in 1970 shows a distraught woman kneeling over the body of a dead student. Unfortunately it so happened that a pole in the background looked like it was coming out of her head. Since this pole was aesthetically unpleasing, it was removed from the picture as published in Life magazine and elsewhere. Amazingly this clumsily doctored version – you can see quite clearly how the pole has been erased – is the one printed in the War/Photography catalogue! (slide #7)

As we move into the contemporary the distinction between art and documentary becomes increasingly hard to sustain—or to put it the other way around, the No-Man’s Land between the two grows ever larger—as shown in works by color photographer Luc Delahaye (slide #8) and photojournalist Damon Winter’s Gurskey-esque view of a plane-load of troops “Flying Military Class” (slide #9). In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag argued that Jeff Wall’s “fictional” image “Dead Troops Talk (a vision after an ambush of a Red Army patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan)” was among the most successful war photographs of recent times. (note: Wall’s image is not part of the War/Photography exhibition) So perhaps Peter van Agtmael’s well-known shot of a line of U.S. troops sheltering from the downdraft of a helicopter in a rocky grey landscape in Nuristan, Afghanistan, in 2007, works on us powerfully for two reasons. (note: van Agtmael’s image is not part of the War/Photography exhibition) First because a compositional similarity to W. Eugene Smith’s shot of Marines sheltering from an explosion on Iwo Jima in 1945 (slide #10) establishes its place in the heroic and noble tradition of documentary photography. Second, because an uncanny resemblance to Wall’s image tacitly acknowledges that the fictive now sets a standard of authenticity to which the real is obliged to aspire.

The relationship between Wall’s large works and the scale and ambition of history paintings has often been remarked on. But Gary Knight’s picture from Dyala Bridge, Iraq, 2003 (slide #11) achieves an even more remarkable relationship with the art of the past. A photograph taken in the immediate aftermath of fighting, it combines the documentary immediacy and evidential power of the best photojournalism with the epic grandeur of history painting.

Geoff Dyer is an award-winning writer and journalist. See more of his work here.

WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath will open at the Museum of Fine Art Houston on Nov. 11, 2012. The exhibit will then travel to Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; and Brooklyn Museum through February 2014.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com