With all due respect to the Who, we will get fooled again. That’s what humans do. At one time or another, we suspend disbelief about virtually everything. And why not? As social creatures, we’re wired to trust others.

But what about when we know, with absolute certainty, that someone’s trying to put one over on us and rather than resisting, we embrace it? What does it say about the power of denial, not to mention our thirst for entertainment, when we actively seek out and celebrate artfully executed trickery?

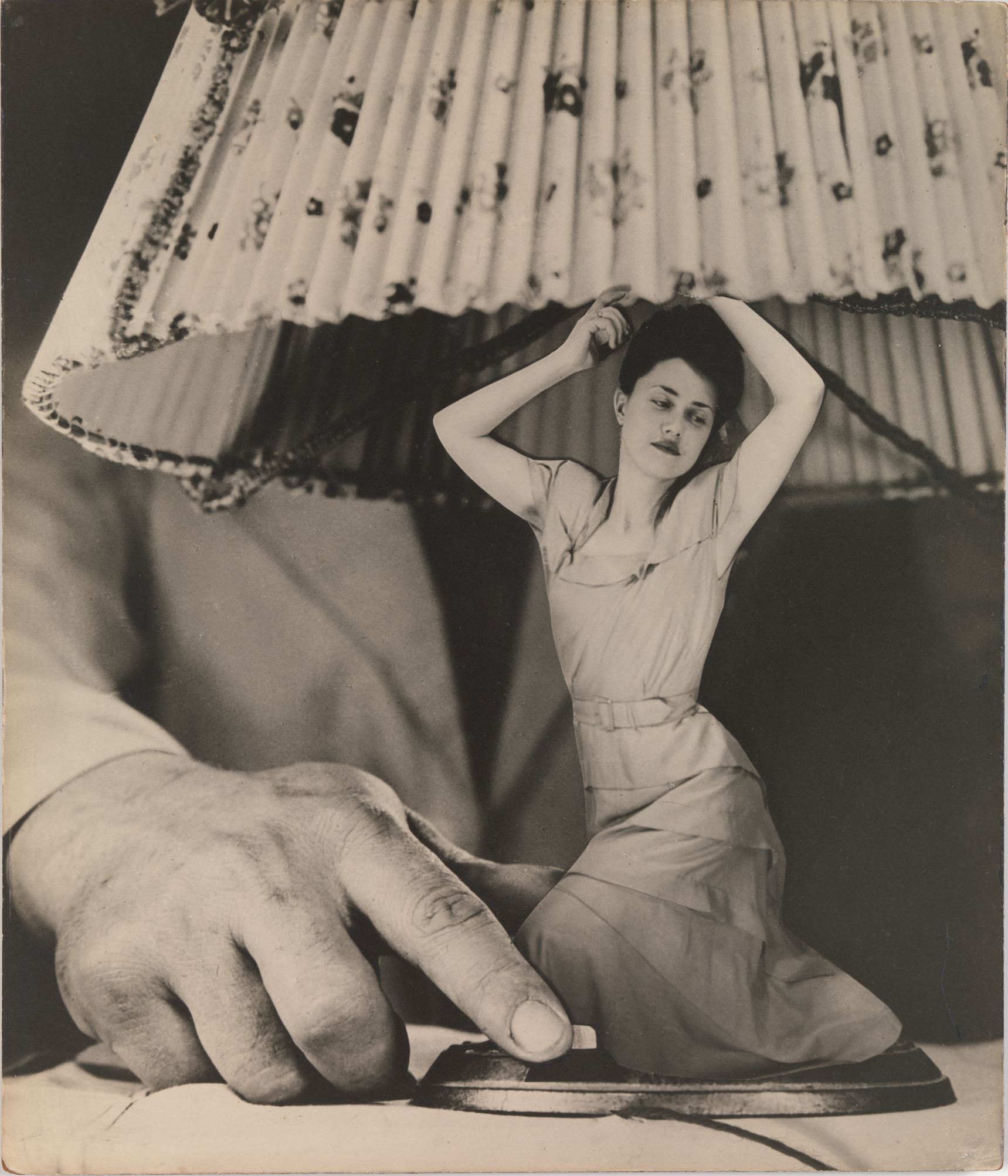

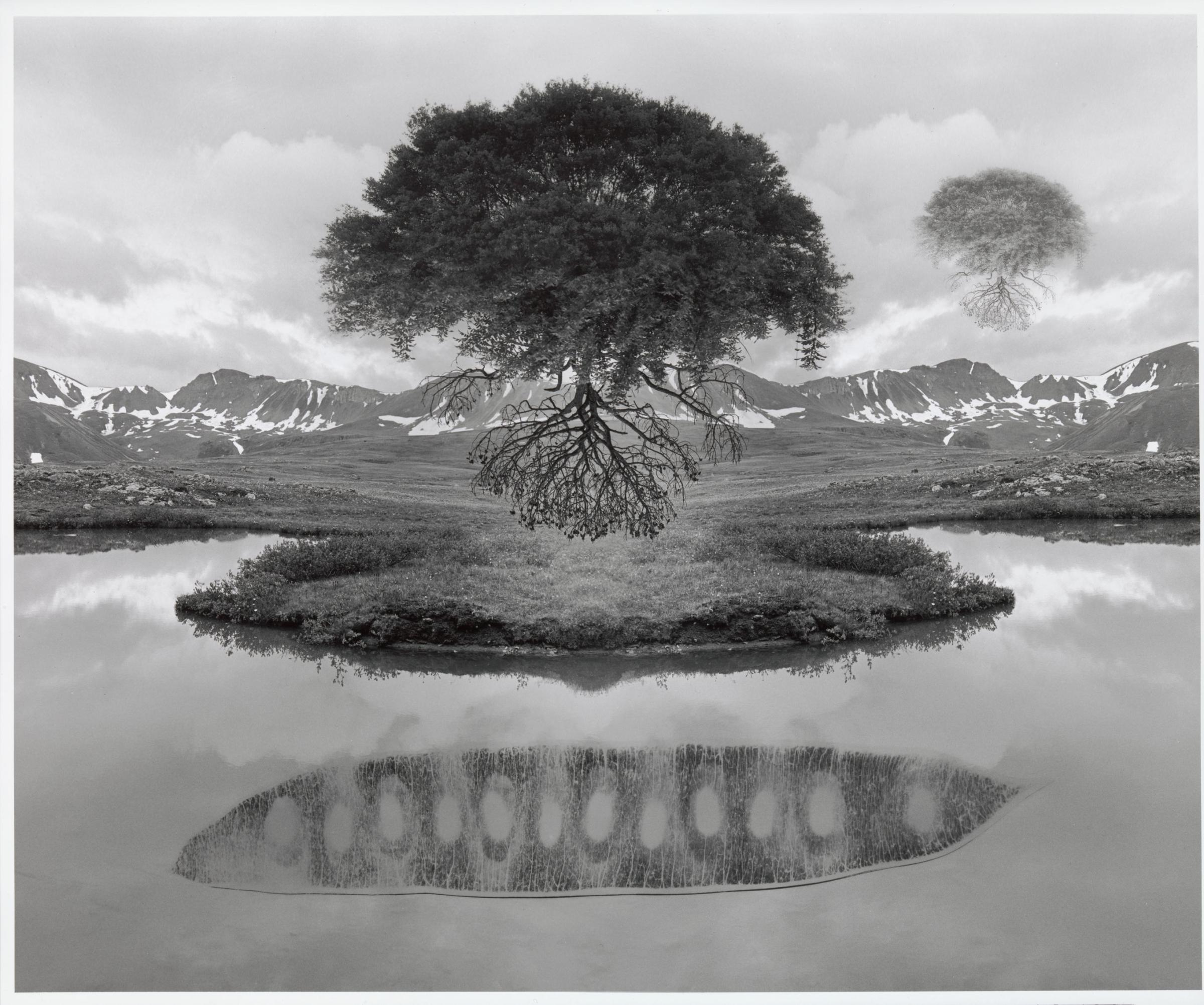

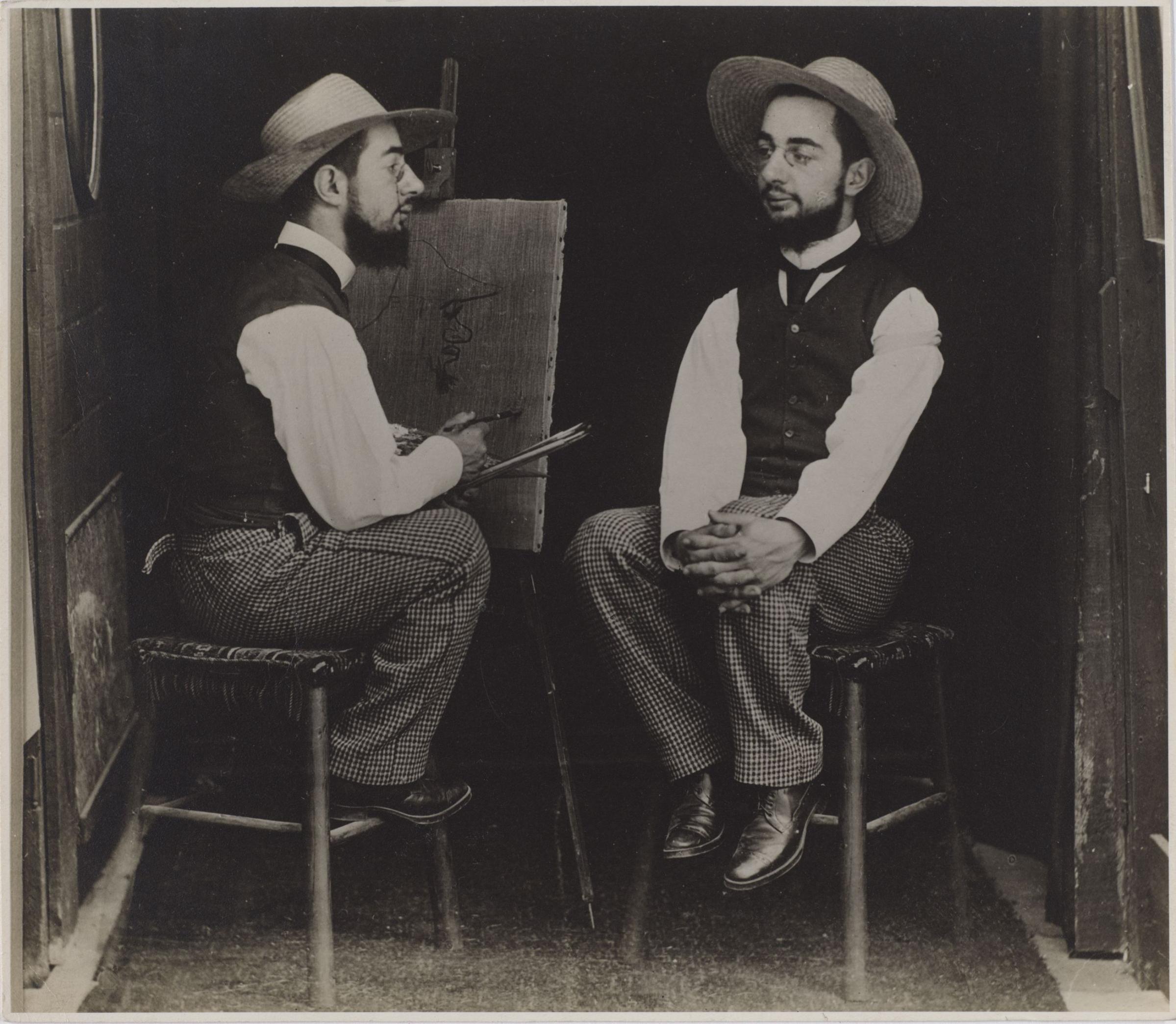

A new show at the Met, Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop, shines a thoughtful light on the work of men and women who, throughout the history of the medium, have playfully (and, occasionally, with more sinister motives) doctored their own and others’ images. Not content with merely presenting the works themselves, though, Faking It also holds up something of a funhouse mirror to the viewer’s preconceptions of what photography really is—and what it means.

After all, if photographers, printers and others involved in the craft have for centuries been altering the “reality” of what the camera captures—as, of course, they always have, and always will—then where is the hard, bright line between, say, a masterwork of photojournalism tweaked and perfected in the dark room and a photo adroitly doctored to make a political point? Professional photo editors might be able to say, with absolute sincerity, “That hard, bright line exists here.” But for the casual observer, the lay viewer, that distinction might feel like little more than an academic splitting of hairs; what matters is that a picture elicits a response—and with few exceptions, the images in Faking It do just that.

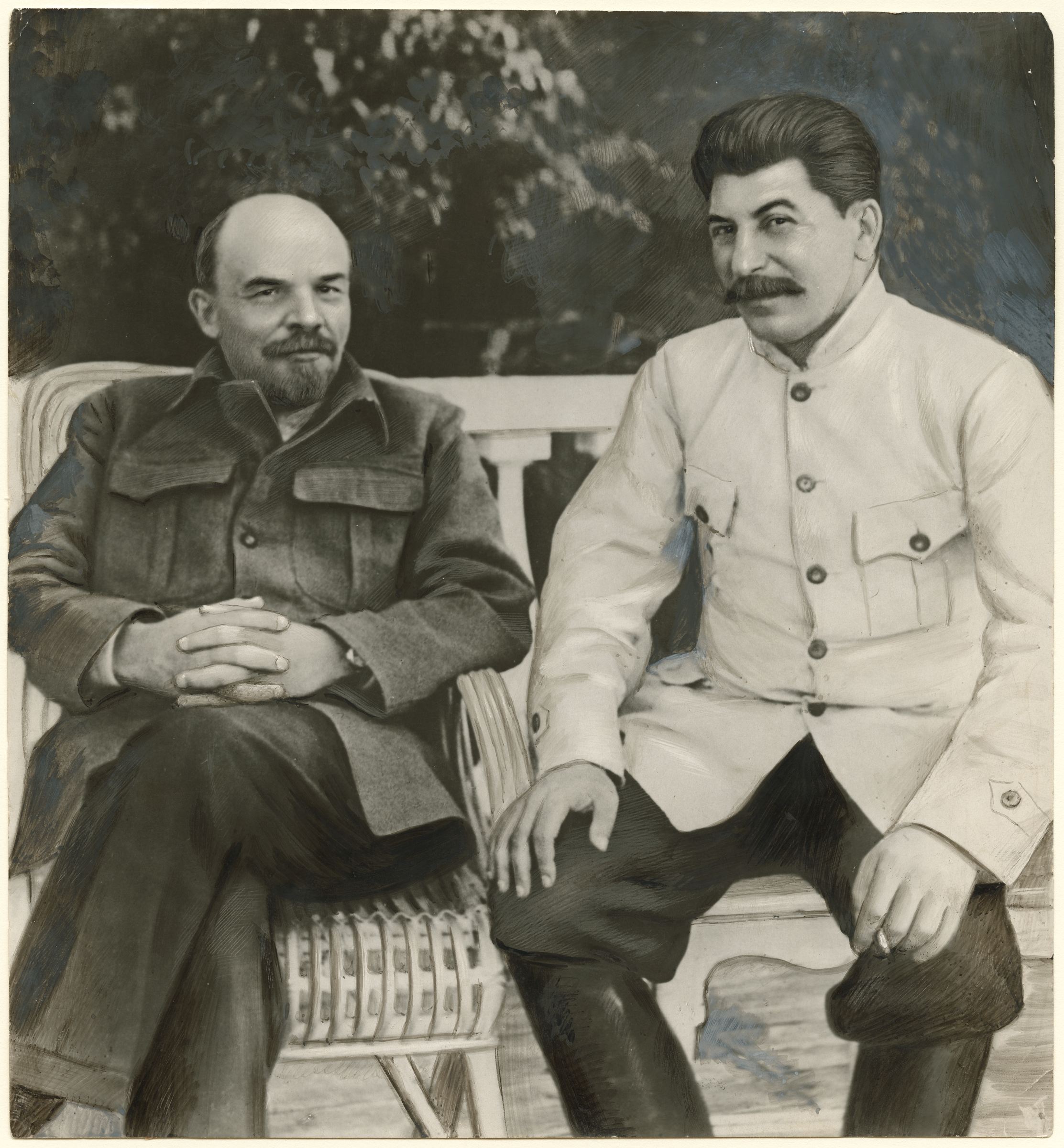

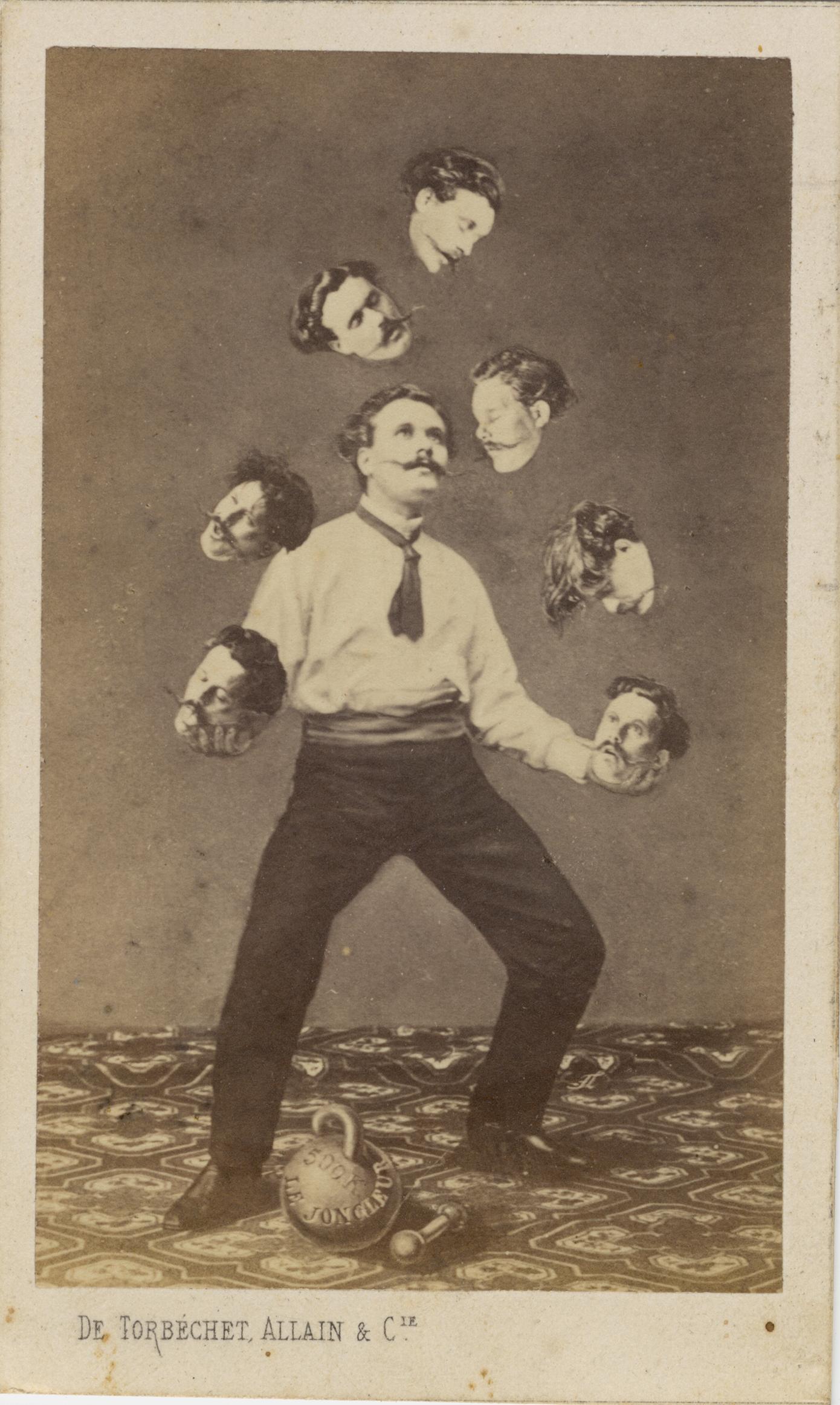

More than a few pictures in the show are memorable for the very reason that they are so obviously, to our contemporary eyes, manufactured. A French artist’s photo made to look like that of a man juggling his own head (slide 8 in the gallery above) might have stunned people in the 1880s; today, not so much—even if we can appreciate the deliberate effort and even the intent that went into creating it. An image of two Soviet premiers seated together, meanwhile, is so clearly an (altered) attempt to consecrate the mass-murdering Stalin as the rightful successor of Lenin that the picture would be comical if we didn’t have such a dreadful understanding of how brutal Stalin’s decades-long reign really was.

Other photos strike a chord for the simple reason that they are, by any measure, beautiful. The dream-like “Orpheus Scene” (1907) by the early fine-art photographer F. Holland Day is so wonderfully moody that, at first glance, it might be the handiwork of the great French Symbolist painter Odilon Redon.

In the end, perhaps the pleasure we take in these pictures derives not from our sophisticated, skeptical, eminently modern sensibility in the age of Instagram, Pixelmator and the rest, but instead can be traced to a simpler, far more elemental source: our capacity, and our longing, for wonder.

Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from Oct. 11, 2012 through Jan. 27, 2013.

Ben Cosgrove is the editor of LIFE.com.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com