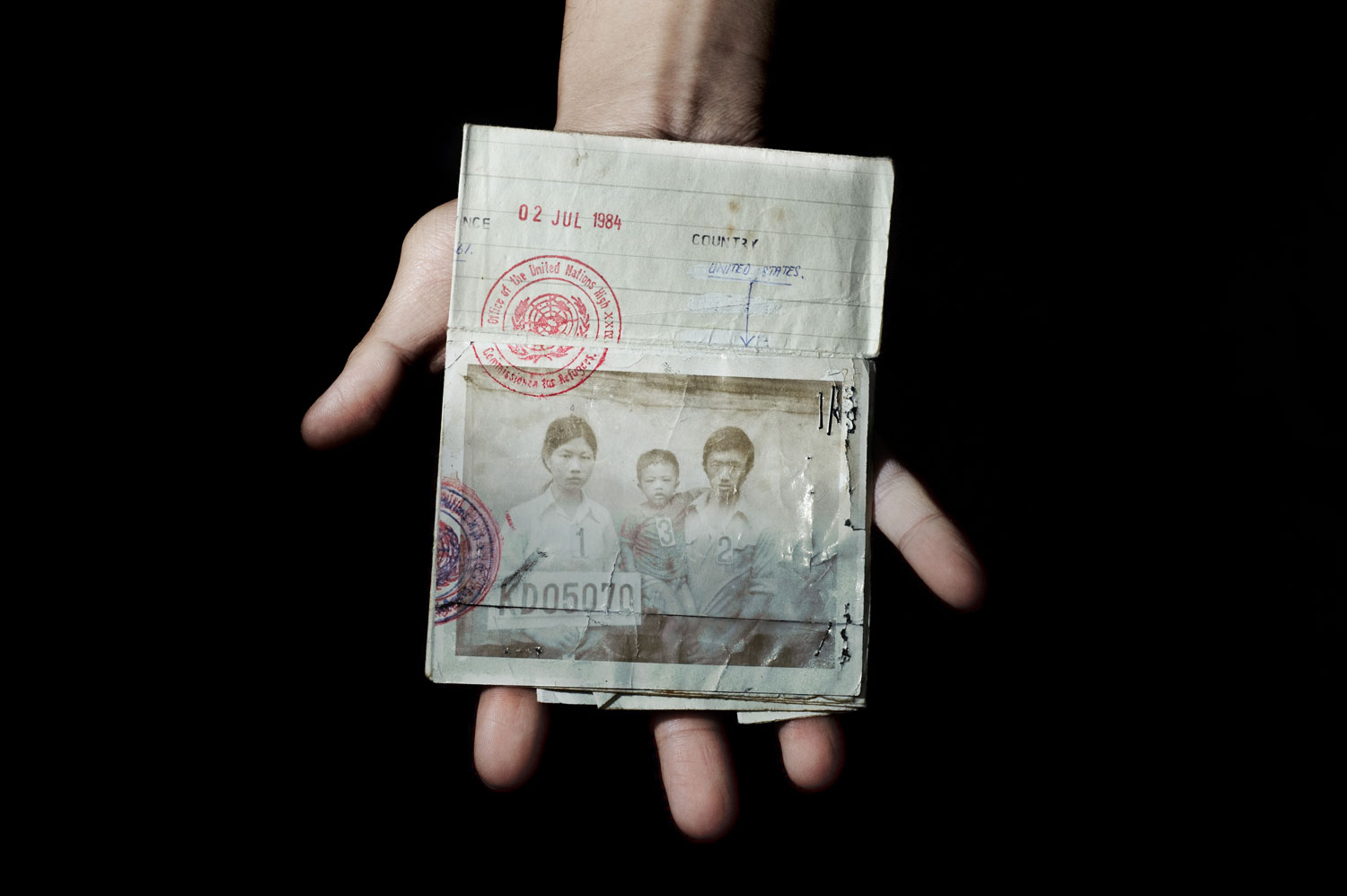

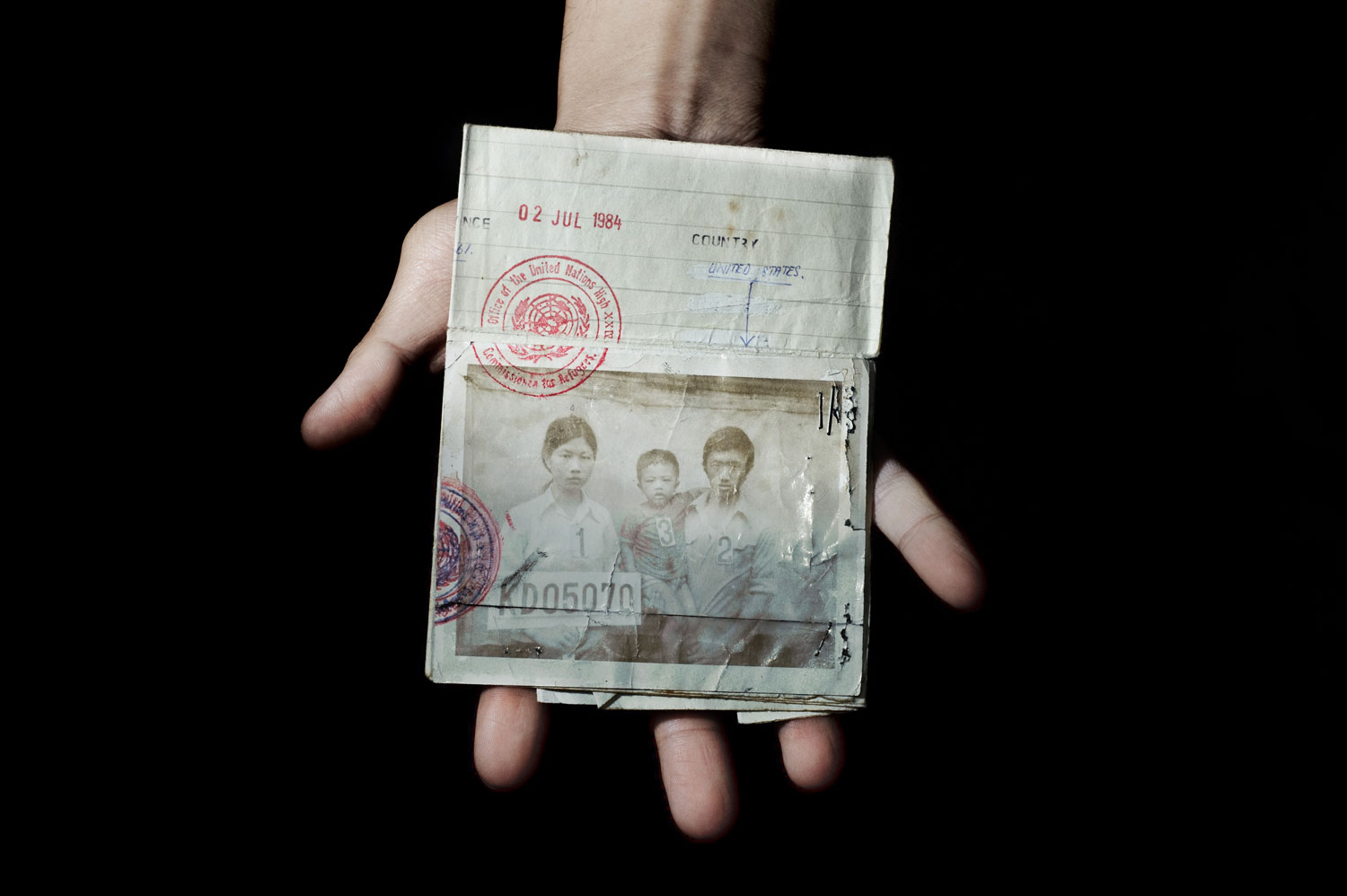

As a son of the Killing Fields born in 1982 in the refugee camp to which my family had fled following the Cambodian genocide, I have struggled for most of my life to understand the legacy of my people. Over the last year, I engaged in a series of conversations with Cambodian-Americans about our history and the complexity of their experience while photographing community members in Philadelphia, Pa.; Lowell, Mass. and the Bronx, N.Y.

The Cambodian people are among the most heavily traumatized people in modern memory. They are the human aftermath of a cultural, political, and economic revolution by the Khmer Rouge that killed an estimated two million, nearly a third of the entire population, within a span of four years from 1975-1979. The entire backbone of society—educated professionals, artists, musicians and monks—were systematically executed in a brutal attempt to transform the entirety of Cambodian society to a classless rural collective of peasants. That tragedy casts a long shadow on the lives of Cambodians. It bleeds generationally, manifesting itself subtly within my own family in ways that I am only starting to fully comprehend as an adult. It is ingrained in the sorrow of my grandmother’s eyes; it is sown in the furrows of my parents’ faces. This is my inheritance; this is what it means to be Cambodian.

After surviving the Killing Fields, my family, along with hundreds of thousands of survivors, risked their lives trekking through the Khmer-Rouge-controlled jungle to reach a refugee camp in Thailand. There, my mother had what she believes to be a prophetic dream. In a field, an entire city’s worth of women were clawing with their bare hands in bloodstained dirt searching for an elusive diamond. To the disbelief of everyone in the dream, she serendipitously stumbled upon it wrapped in a blanket of dirt. The following day she discovered she was pregnant with me. The significance of this didn’t dawn on me until I started photographing this project. It was a vision of hope and renewal, that we as Cambodians are endowed with an incredible resilience and strength in human spirit. I have seen this in the faces of Cambodians I have photographed and have been incredibly humbled. In the words of my mother, it is a miracle to simply exist.

As a result of the unique demographic circumstances of the genocide, there has been a paucity of reflection within the Cambodian community. Many second-generation Cambodians I have interviewed learned about the Killing Fields through secondary sources, from the Internet and documentary films. Such conversations were non-existent at home. Exacerbating the silence is an inter-generational language barrier; most young Cambodian Americans cannot speak Khmer, the Cambodian language, while their parents and grandparents are incapable of speaking English. As a result, we are the literal manifestation of Pol Pot’s attempt to erase Cambodia’s history and culture. However, in spite of this void, there exists a growing movement of young and empowered Cambodians—academics, artists, musicians, and activists—who are trying to bridge this generational chasm.

For months, the senior surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge have been tried for crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide in Cambodia by a United-Nations-backed international tribunal that was established in 2006. Over half a decade later, and at a cost of an estimated $200 million, the court has prosecuted only one individual, Kaing Guek Eav, known as Duch, who presided over the execution of more than 16,000 in Cambodia’s most infamous prison. On Feb. 3, the tribunal extended his sentencing to life in prison. In spite of this ruling, the court is on the verge of collapse because of corruption and a lack of political will by the government to proceed beyond the trials of only the highest ranking surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge. This is heartbreaking. I asked my mother how she felt about this: she responded, almost tearfully, that this in and of itself could never take back her suffering. Many Cambodians I have spoken with in the course of photographing this project have echoed this sentiment. But I am convinced that justice and healing must emerge from the collective will of my people.

Pete Pin is a Cambodian-American documentary photographer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. He was a Fellow at the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund, which supported the Bronx portion of his long-term project on the Cambodian diaspora. More of his work can be seen here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com