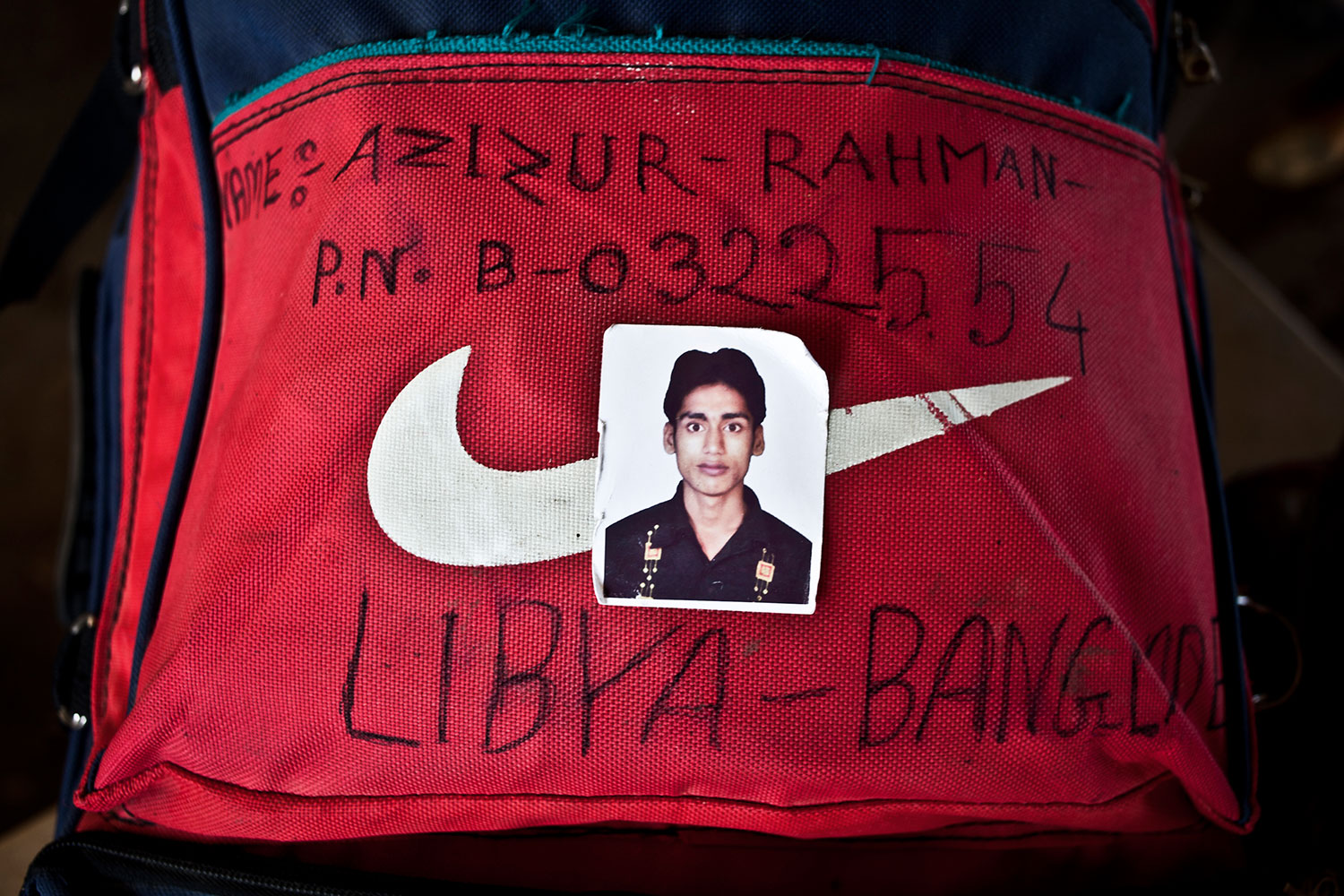

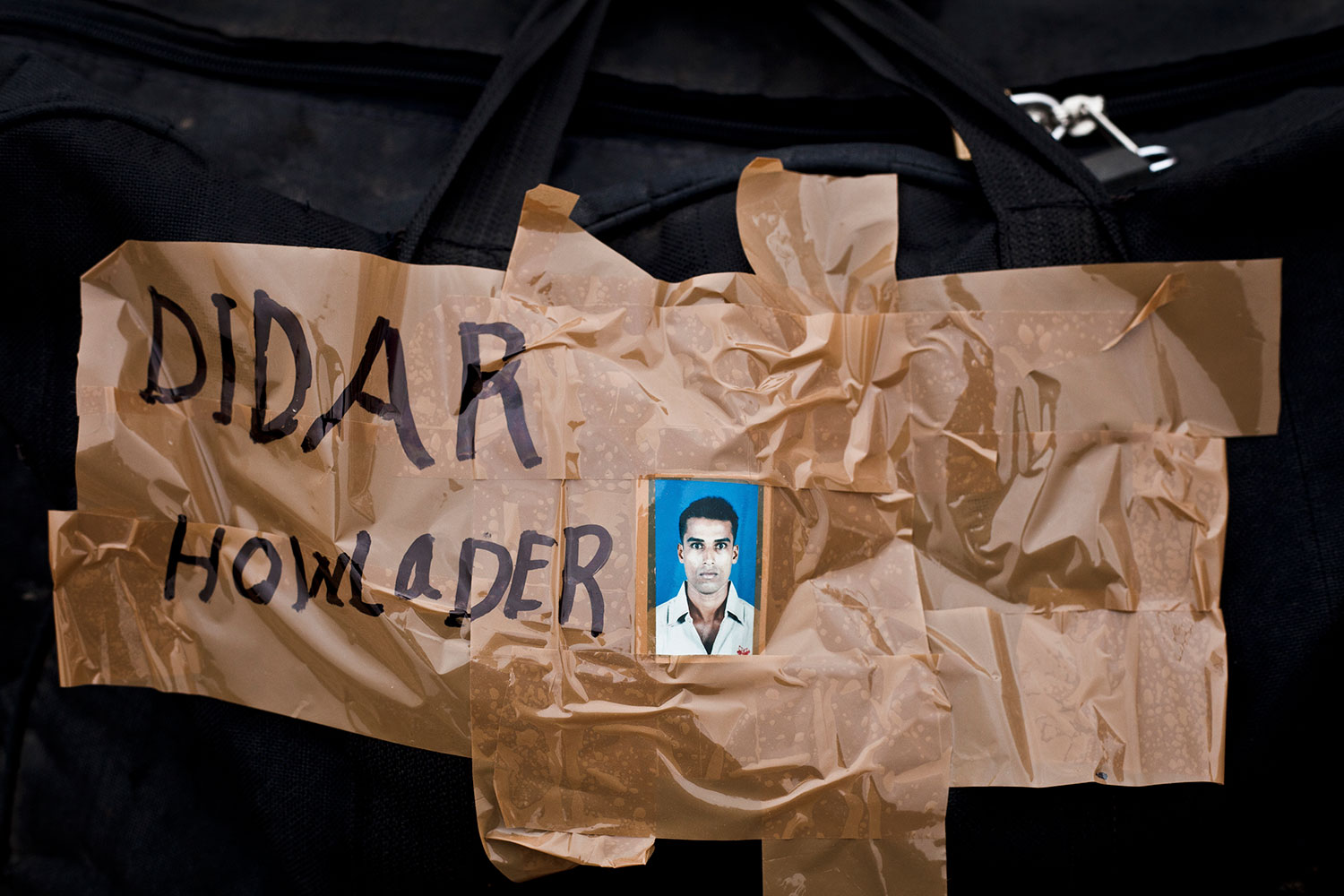

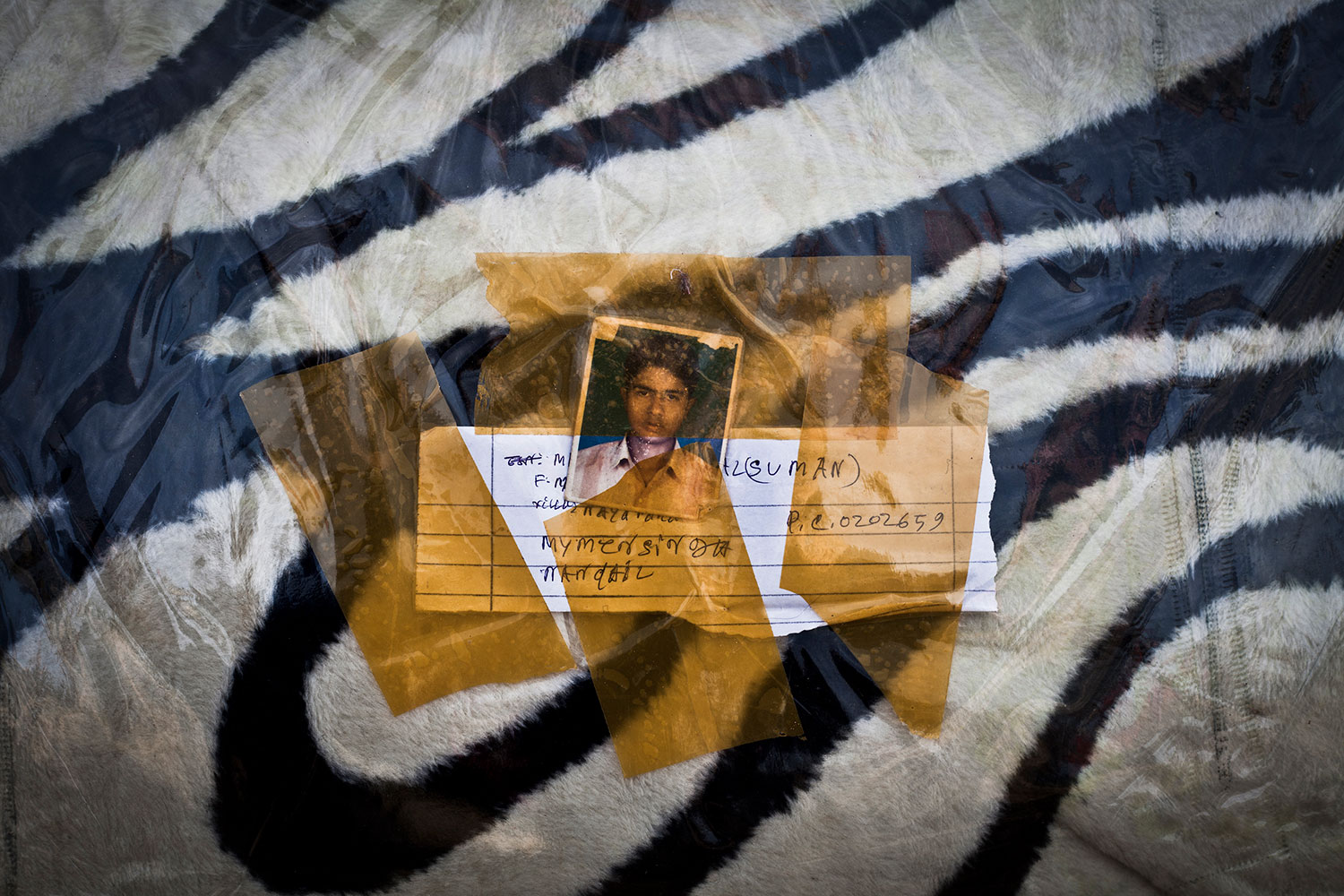

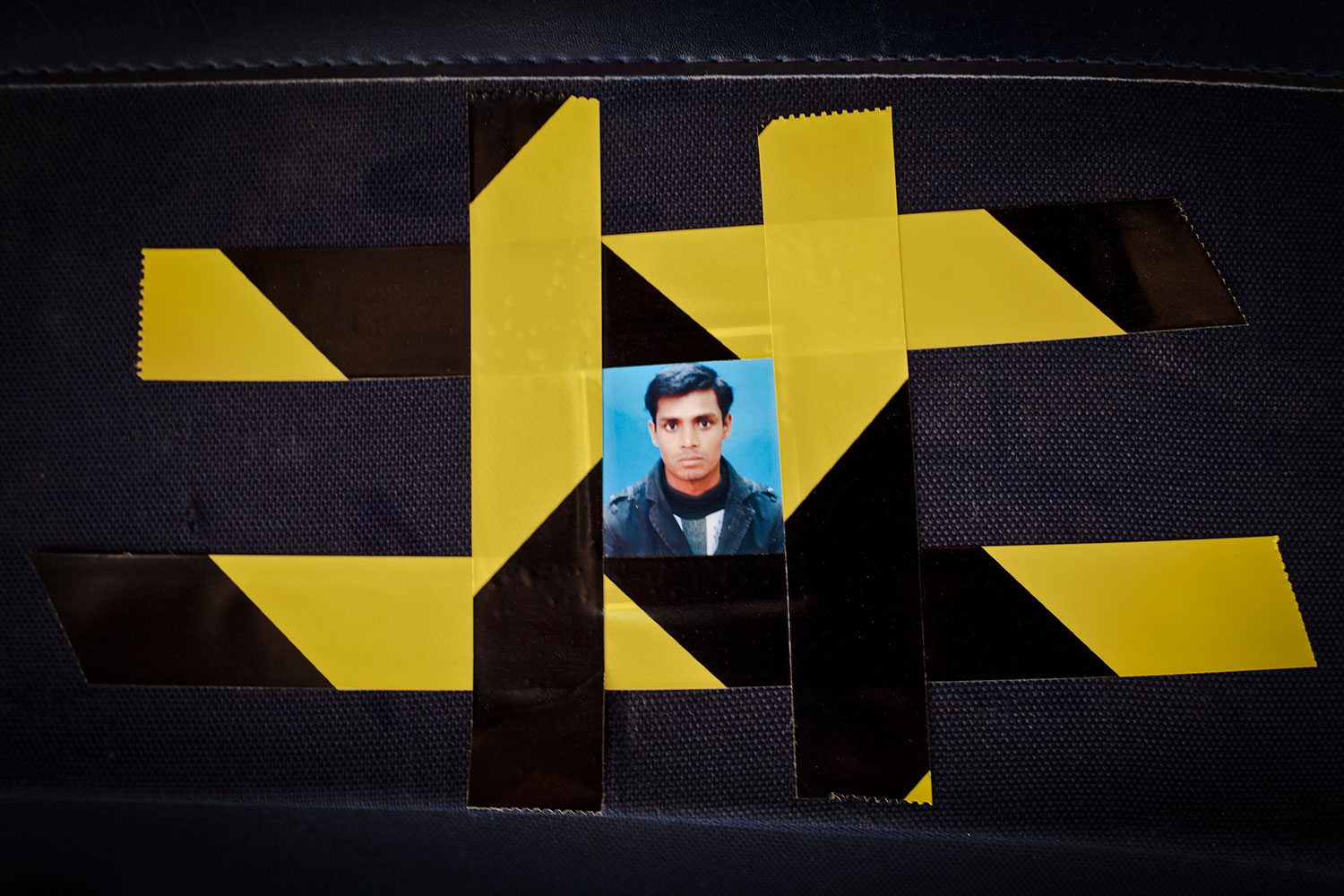

Didar Howlader, Azizur Rahman and many others were worried that all they had left would soon disappear, too. In the vain hope of finding their bags again — in case that happened — the men attached photo IDs to the small sacks and suitcases carrying their belongings as they set out across the Libyan border into Tunisia.

The devastated lives and livelihoods of foreign migrant workers have been among the most tragic and overlooked consequences of Libya’s ongoing civil war. Nearly 70,000 Bangladeshi nationals were working in Libya; mostly for Chinese, South Korean, European or Libyan construction companies when the violence erupted in February 2011.

Like most Libyans, the uprising caught the foreign workers by surprise. But unlike many Libyans, the Bangladeshis, Chinese, Africans and other foreign nationals who had come to Libya to make a modest living had no interest in local politics. None of that mattered when clashes erupted across the country between the forces loyal to Col. Muammar Gaddafi and the rebels. Many foreign workers found themselves alternately trapped in the crossfire — or fleeing for their lives.

Tens of thousands have managed to escape, traversing perilous desert routes rife with danger, harassment and threats to arrive at overcrowded and under-supplied refugee camps on the Tunisian and Egyptian borders, or at ports on the country’s Mediterranean coast.

With the help of the World Bank and the Bangladeshi government, 35,000 migrants have been able to return to Bangladesh in the aftermath of the uprising – most of them heavily in debt, and with no ready means of earning a living at home. Their traumatic return also underscores the difficulties that many overcame to get to Libya in the first place; many have sold their homes and mortgaged their own lives for the opportunity to provide for their families by earning income overseas. Suddenly deprived of that option, desperation is mounting.

Perhaps that is why, in passing out of Libya, the Bangladeshis hold tight to what little they have managed to salvage; attaching photos to their bags with the hopeful expectation that not everything has to be lost.

Francesco Giusti, a freelance documentary photographer based in Milan, produced this project in collaboration with Prospekt photo agency. Interested in social realities, communities and identity-related issues, he has photographed in Haiti, Congo and Egypt among other places. His project Sapologie won the 2nd Place Prize for Arts and Entertainment Stories at the 2009 World Press Photo Awards.

Produced By Myles Little

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com