Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson has spent years photographing Iceland’s volcanoes. His images of last year’s Eyjafjallajökull eruption were featured prominently in the pages of TIME. Sigurdsson spoke with TIME about his experiences documenting this year’s eruption of the Grimsvotn volcano from an aircraft.

On Sunday morning, Icelandic photographer Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson received a phone call from a friend reporting unusual seismic activity — an indicator that the Grimsvotn volcano might erupt within the next half hour. Sigurdsson’s 30 years of experience photographing Iceland’s volcanoes kicked in and within minutes, he was speeding to the local airport.

“I have a pilot who’s a genius. We’ve worked together for a long, long, long time. When there’s an eruption, there’s a plane and pilot waiting for me — they know I am going immediately,” the photographer tells TIME.

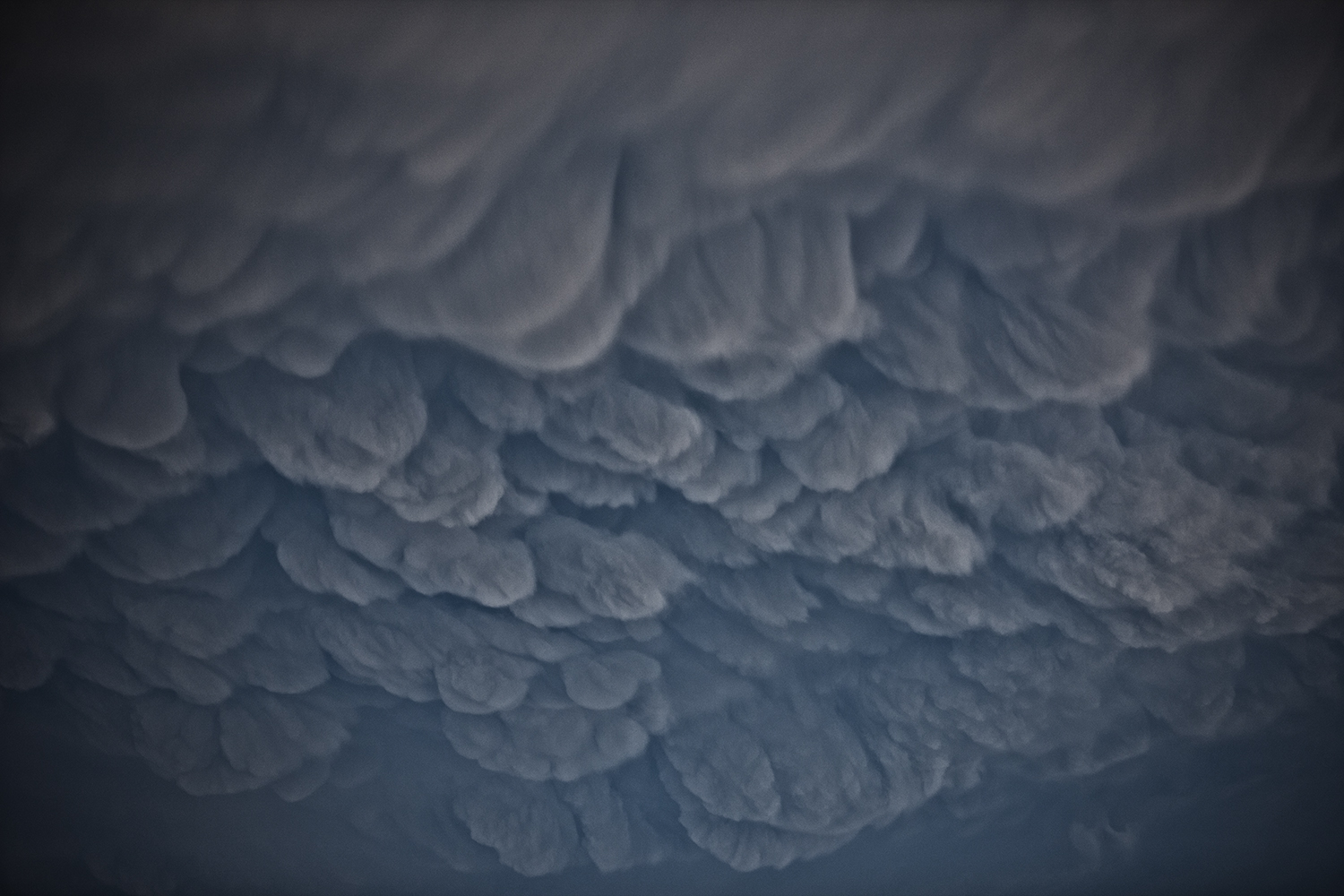

Sigurdsson’s wife and a videographer friend sat in the back seat of the six-person Cessna as it buffeted against the heavy winds that often sweep the country. Turning upwind from the eruption as the plane climbed to 10,000 feet, Sigurdsson spotted the cloud of ash spewing from underneath the Vatnajökull glacier, Europe’s largest.

“When you have an eruption so big, you [get] a mushroom shaped cloud like a nuclear bomb. The photos I shot are at the bottom of the mushroom—30km wide and 15km high. It was huge.”

But what has people concerned is the volcanic ash. Last year’s Eyjafjallajökull eruption produced an ash cloud that suspended European air traffic for weeks. Volcanic ash particles pose a threat to aircraft engines, disrupting the travel of Heads of State and vacationers alike. Sigurdsson’s images of Eyjafjallajökull were featured in the pages of TIME.

He is able to fly near the volcano because the heavy winds quickly carry the ash south into Europe — he can get incredibly close as long as his plane stays upwind of the ash plume.

“I’m not flying into the ash, but I can fly over it, I can fly under it, and I can fly upwind of it.”

Sigurdsson removes the door from the plane so he doesn’t have to shoot through the plastic windows. Using both wide-angle and telephoto lenses, he perches in the doorway while trying to counter vibrations from the plane and jet stream as well as airborne dust.

“My cameras are almost ruined in the ash. It’s so fine…it’s the finest grain I’ve ever seen or touched in my life. It’s terrible. It’s in my eyes, it’s in my ears, my clothes, my hair — doesn’t matter how often I shower, it’s there all the time,” Sigurdsson says.

At its peak, the Grimsvotn volcano spewed into the air an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 tons of ash per second.

“In terms of size, there was more ash in one day than in forty days of last year’s eruption.”

Although it’s mostly finished now, the ash has completely covered parts of Iceland, shrouding entire villages in thick layers of dust.

“If you hold your hands in front of you, you cannot see them. There is total darkness and it is difficult to breath,” he says.

After making two three-hour flights in 48 hours, Sigurdsson’s next trip will be to the crater itself. He’s spending the night tonight at the Vatnajökull glacier with a team from Reykjavik. Driving a specially modified Land Rover with 44-inch tires, they plan to peer inside the volcanic crater.

“The worst is over, and now the clean-up can begin,” Icelandic Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurdardóttir said on Wednesday.

—Vaughn Wallace

Ragnar Th. Sigurdsson has worked as a photographer since age 16. Starting out as a press photographer and later working at his own advertising firm, Sigurdsson now shoots stock exclusively for Getty and Corbis. His work is available through Arctic-Images.com.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com