Soon after midnight on April 1, a separatist group calling itself the Kharkov Partisans issued another one of its video warnings to the Ukrainian government. It claimed that within the next 48 hours a bomb would explode far behind the front lines of the war in eastern Ukraine. “As of now, the earth will begin to burn beneath your feet,” said the group’s spokesman, Filipp Ekozyants, in the message to Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko and his top security officials.

Sure enough, the bomb arrived. Though reports have been conflicting as to the damage it caused, a large explosion rang out in the southwestern part of Kharkov, Ukraine’s second largest city, within 24 hours of the Partisans’ threat. Police denied that any bombing had occurred that night, though that seems to be part of a cover up. “The explosion did take place,” says Andriy Sanin, the head of the local branch of Right Sector, a nationalist paramilitary group that works in league with Ukraine’s armed forces. “It appears to have been an act of intimidation,” he says, declining to give further details. In a follow-up video on April 3, the Partisans claimed that the attack had targeted a military convoy, killing a dozen Ukrainian servicemen.

But whatever the details of that bombing, it would hardly have been the first attack attributed to this guerrilla group. In interviews with TIME over the past two months, the group’s spokesman, a former wedding singer now based in western Russia, has claimed responsibility for a spate of bombings, mostly targeting military and industrial installations in the region of Kharkov, which lies right on the border with Russia. “Our goal is to liberate the people of Kharkov,” Ekozyants says in the first of several interviews. “And we will fight until the current authorities are weak enough to allow this.”

Numbering more than a dozen in the past few months alone, the bombings in Kharkov and other cities have marked a grim turn in Ukraine’s year-old conflict. The Russian-backed separatists in Ukraine’s eastern regions have managed to seize control of two major cities and large chunks of the border with Russia. But they are clearly not satisfied with the extent of their possessions. Even amid the ceasefire that Russian President Vladimir Putin negotiated and signed with President Poroshenko in February, the bombing of Ukraine’s cities has only intensified. The war now seems to be shifting from the use of tanks and artillery to the methods of terrorism and guerrilla warfare.

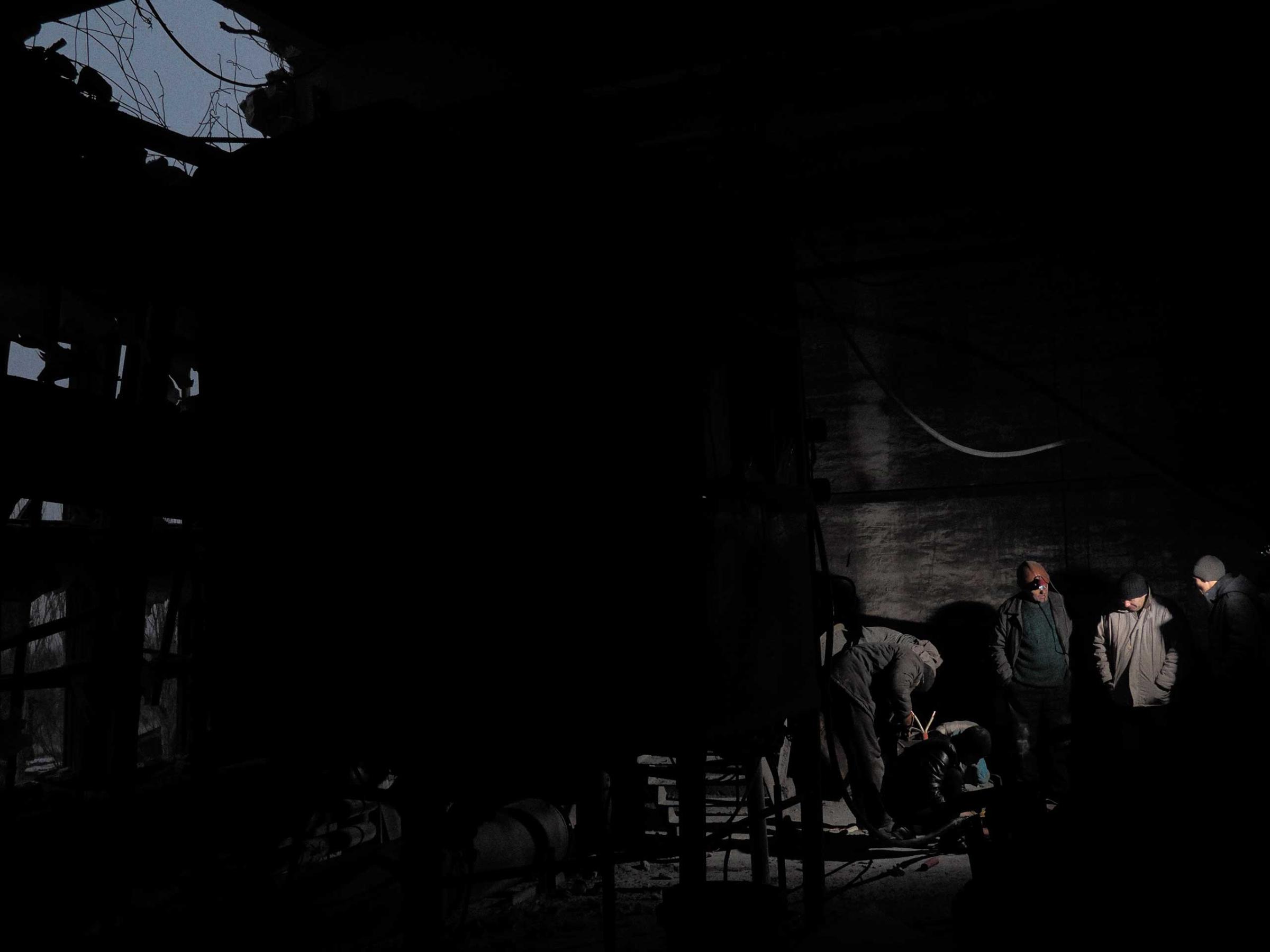

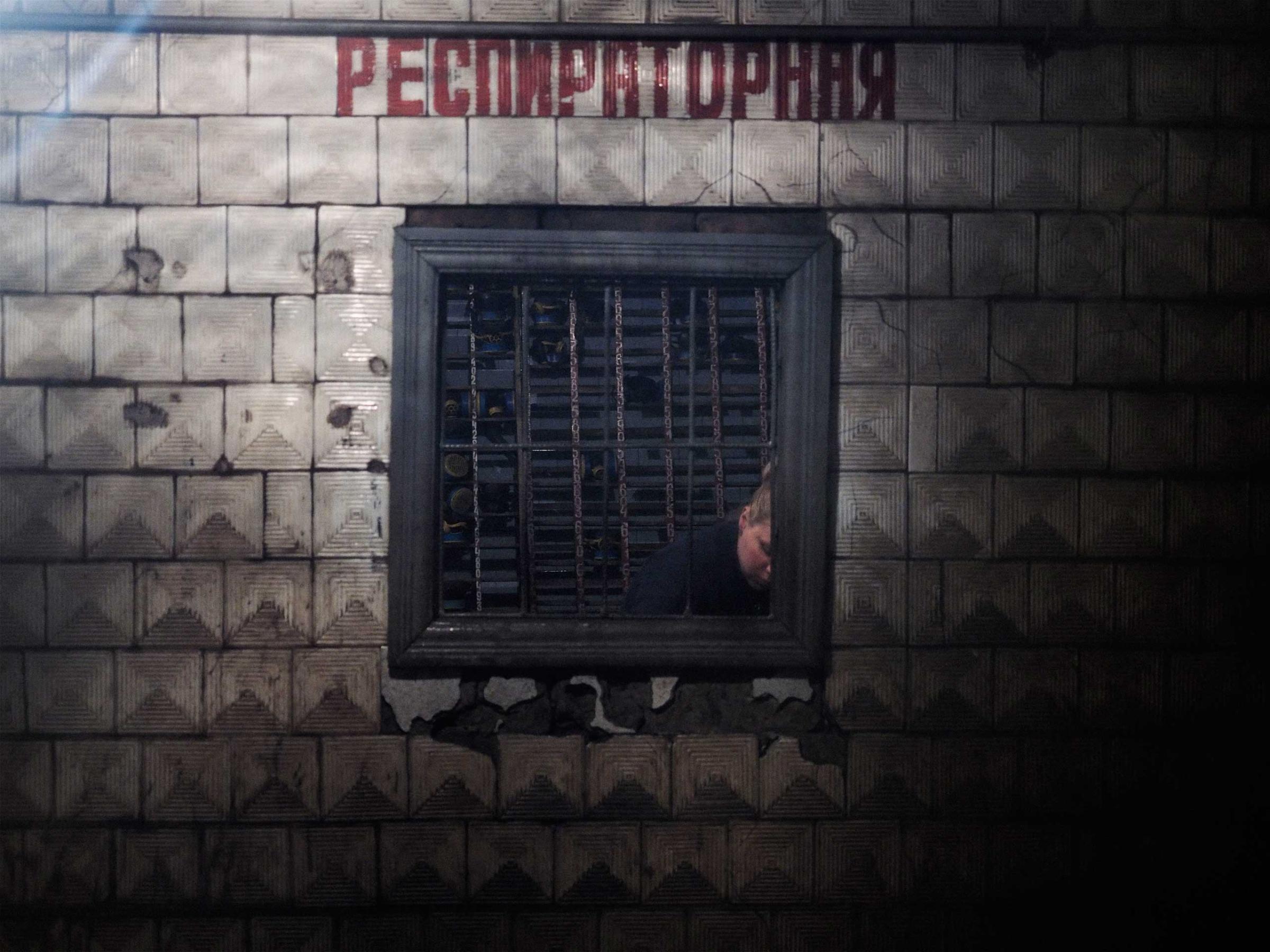

Beneath the Front Lines of the War in Eastern Ukraine

The goal of these attacks, says Ekozyants, is to paralyze the Ukrainian authorities and inspire locals to join a separatist revolt against them. But there seems to be some debate within his organization about the admissible means of achieving this. About two hours before Ekozyants issued his warning on April 1, he told TIME that the November bombing of a crowded bar in Kharkov was the work of a radical cell of the Partisans. Eight people were wounded in that bombing, two of them critically.

From their bases in Russia and the rebel-held cities in eastern Ukraine, the more moderate leaders of the Partisans then issued a ban on attacking civilians, in part to avoid a popular backlash against their methods, says Ekozyants. “After what happened at [the bar], our coordinating council issued a directive to all our cells, saying any more actions in places where there are peaceful people will be punished by lethal means.”

But the lethality of the bombings in Kharkov have still continued to increase. The deadliest confirmed attack struck on a religious holiday, Forgiveness Sunday, Feb. 22, the day in Eastern Orthodox tradition when believers are meant to repent for their sins. It was also the day when many in Ukraine marked the one-year anniversary of their country’s revolution, which brought a pro-Western government to power last winter. Sanin, the local paramilitary leader, was leading a march of commemoration that afternoon through Kharkov, and as his column set out through the city, an anti-personnel mine exploded at the side of the road, sending a shockwave full of shrapnel into the crowd. Four people were fatally wounded, including two teenage boys, and nine others were hospitalized.

“In the first seconds there was panic,” Sanin recalls. “Everyone was screaming, running, and there was a real risk that the victims would get trampled where they lay.” Sanin appears to have been one of targets of the attack, but he escaped with minor injuries.

A few days later, Ukraine’s state security service, the SBU, released what it claimed to be a video of the bomber’s confession. Because his face in the footage is blurred and his name has not been released, it has been impossible to verify the authenticity of the SBU’s claims, which have not always been reliable. In a monotonous patter, the alleged confessor claims that an agent of the Russian security services paid him $10,000 to carry out the bombing on Forgiveness Sunday.

For his part, Ekozyants denies that the Kharkov Partisans had anything to do with that attack. But some of his allies in the rebel movement still believe the bombing was justified. “There were no accidental victims there at that march,” says Konstantin Dolgov, a leading pro-Russian separatist in Ukraine. “They were all the same people who were fueling a big civil war in Ukraine. They were calling for the death of Russians, of Russian-speakers,” says Dolgov, who denies any involvement in that bombing. After a pause, he adds: “There’s a good Russian saying: You sow the wind, you reap the storm. And the storm caught up with them during that march.”

Having started his career a decade ago as an adviser to a pro-Russian governor of Kharkov, Dolgov has emerged as a one of the main links between Moscow and the separatists in eastern Ukraine. He now splits his time between the Russian capital and the rebel stronghold of Donetsk, and he is living proof that the separatists’ ambitions in Ukraine go far beyond the territories they currently control. Russia seems to support his message. On Kremlin-owned television channels, he is a fixture on political talk shows, frequently cast as the benevolent face of Ukrainian separatism.

One afternoon in March, he agreed to meet me at a restaurant in Moscow across the street from the offices of the Russian Presidential Administration, where he sat in a pressed suit with a little separatist flag pinned to his lapel. Despite the resistance of Ukrainian authorities, he claims it is only a matter of time before Kharkov falls to the separatists. “But the liberation is only possible from the outside at this point,” he says. All the local separatists in Kharkov have been jailed or forced to flee the city. So there are now “at least 1,500 men” from Kharkov fighting in various rebel factions in other parts of eastern Ukraine, he says. “They all hope to return home and take revenge for their murdered comrades.”

Ekozyants, who calls Dolgov a close associate, takes a somewhat different view. Through the bombing campaigns of the Partisans, he believes the Ukrainian authorities can be weakened from within, allowing the local separatists to organize an uprising in the city. “All we want is to create a government of Kharkov that will listen to the people,” he says. The ultimate aim is for the city to hold a referendum on secession from Ukraine, much as the region of Crimea did last spring before it was annexed into Russia. “If a majority of people in Kharkov vote to join up with Burkina Faso, then we will join Burkina Faso,” Ekozyants says. “But let the people decide.”

His success as a mouthpiece for separatism in Kharkov derives in part from his earlier fame. Long before the war in Ukraine broke out last spring, Ekozyants was well known in the city as a composer and singer of maudlin ballads, which he would often perform at local weddings and banquets. (“Eternal love, we live to blindly love,” went one of the refrains in his music video from 2009.) The showmanship has since become a hallmark of his propaganda, which is laced with moody, anti-Semitic diatribes against the “shameless yids” seizing power in Ukraine with help from the West.

In late February, when TIME first contacted him for an interview, he replied by sending back a theatrical nine-minute video – “an address to the American people” – warning of an apocalyptic war that would turn U.S. cities into “giant ruins” if Washington does not withdraw its support for the Ukrainian government. When pressed to comment beyond such bravado, he invited a reporter to visit him in the western Russian city of Ryazan, but backed out at the last minute and only agreed to talk via Skype.

In subsequent interviews, he says most of the financial support for the Kharkov Partisans comes from sympathetic businessmen living in Russia, who transfer funds into his bank account. Asked whether the Partisans receive support from the Russian military or security services, he says some Russian state support does come through the rebel leadership in Donetsk. “We don’t just cooperate,” Ekozyants says of that separatist stronghold. “We are one network. We are the same.”

And Russia clearly tolerates their activities on its territory. The bank account Ekozyants uses to gather donations is at a branch of state-controlled Sberbank, Russia’s biggest lender, in the western Russian city of Rostov. In his spare time, Ekozyants says he still earns extra money singing at banquets in Russia, and he also seems to have access to a television studio in one of the Russian cities where he operates.

In late March, he posted a video of himself in a studio interviewing Igor Girkin, a former agent of the Russian security services who led the separatist militias in their conquest of Ukrainian territory last year. The two of them muse for an hour about the future of the “Russian world,” which they see extending across much of Ukraine. The Russian government, Girkin says, has been too indecisive in pursuing its imperial destiny in these borderlands. “But I always felt that God realizes his will through individuals,” he says. Even when those individuals are prepared to set off bombs in peaceful cities.

Go Inside the Frozen Trenches of Eastern Ukraine

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com