While it’s not clear exactly why Germanwings Flight 9525 crashed into a French mountainside, the black box from the cockpit raises questions about whether mental health issues were involved, and how aviation officials identify and monitor the mental health of pilots.

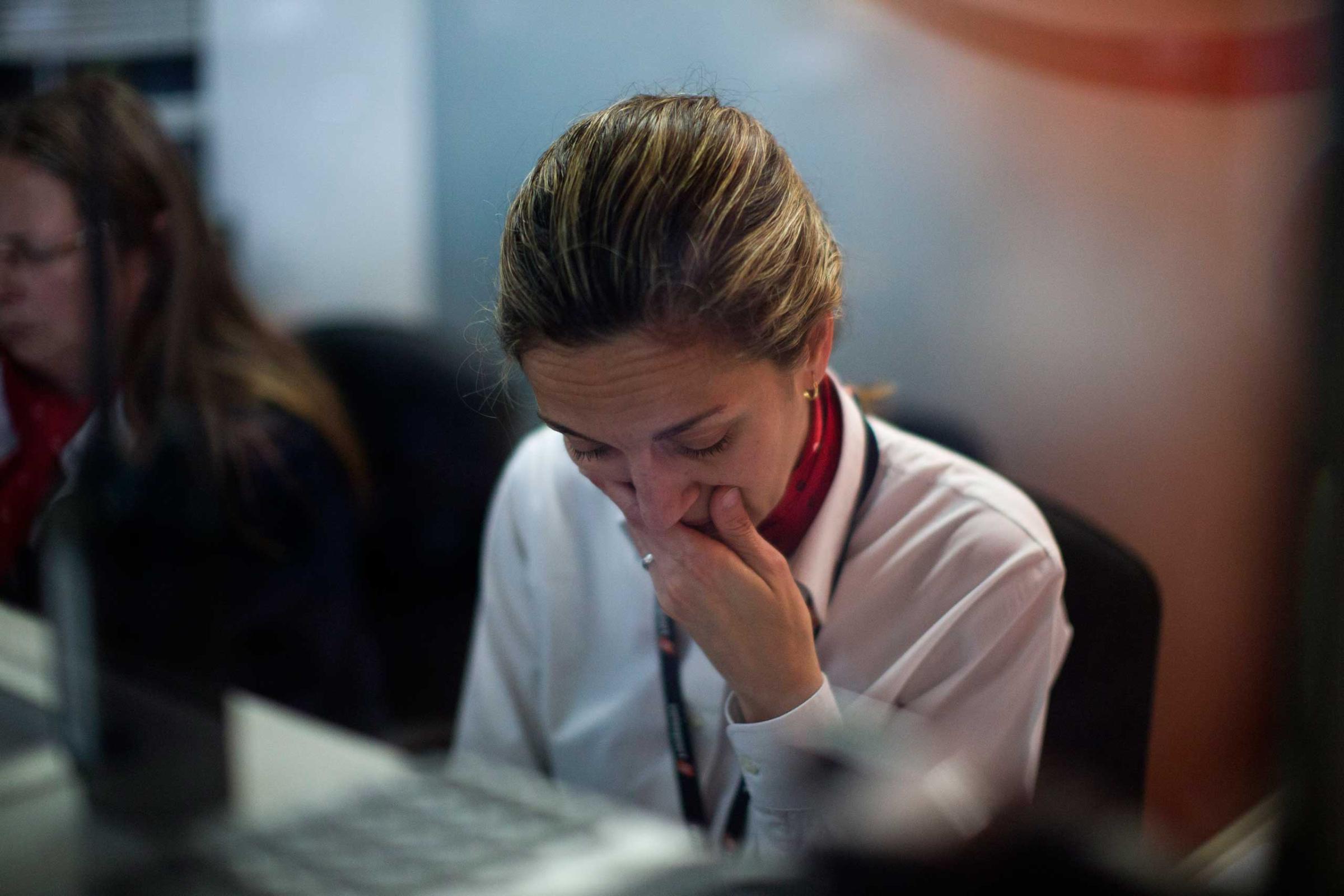

Prosecutor Brice Robin said that the cockpit recordings suggest the lead pilot was locked out of the flight deck after leaving for the restroom, and that co-pilot Andreas Lubitz “voluntarily allowed the aircraft to lose altitude. He had no reason to do this. He had no reason to stop the captain coming back into the cockpit.” As investigators search for a second black box, experts are trying to piece together the reasons why Lubitz acted the way he did. His mental state remains a possible cause.

If the investigation reveals that mental health played a role, it wouldn’t be without precedent. In a 2014 study in the journal Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine, researchers looked at 20 years of data for what they called “aircraft assisted suicide.” From 1993-2012, 24 of 7,244 plane crashes were thought to be deliberately caused by a pilot. That’s less than 1% of the total, but it’s still enough to raise questions about the mental health stressors of pilots.

“I really wish that we had some kind of deeper thinking about this issue, because it’s one of the most difficult in aviation medicine,” says Alpo Vuorio, MD, PhD, the study author and an aviation specialist in occupational medicine at the Mehiläinen Airport Health Centre in Finland. He screens pilots and cabin crew of commercial airlines for health issues—including mental health issues—and says he sees any given commercial pilot once a year for a short visit.

Commercial pilots have to pass a physical and mental evaluation every six months (for those over 40) or once a year (for those under 40) in order to be certified to fly a passenger plane. The emphasis, however, is on the physical and less on the mental, mainly because mental health is harder to quantify.

“You somehow try to see if the pilot is well, and it’s not the easiest thing,” Vuorio says. Pilots answer yes-or-no questions about their mental health, Vuorio says, like if they’ve ever tried to attempt suicide or visited a psychiatrist. “You speak yes or no, but it’s up to you, what you tell,” he says. Pilots can visit several different locations for these examinations, he says, and if they don’t occur in house, past data don’t appear on the screen.

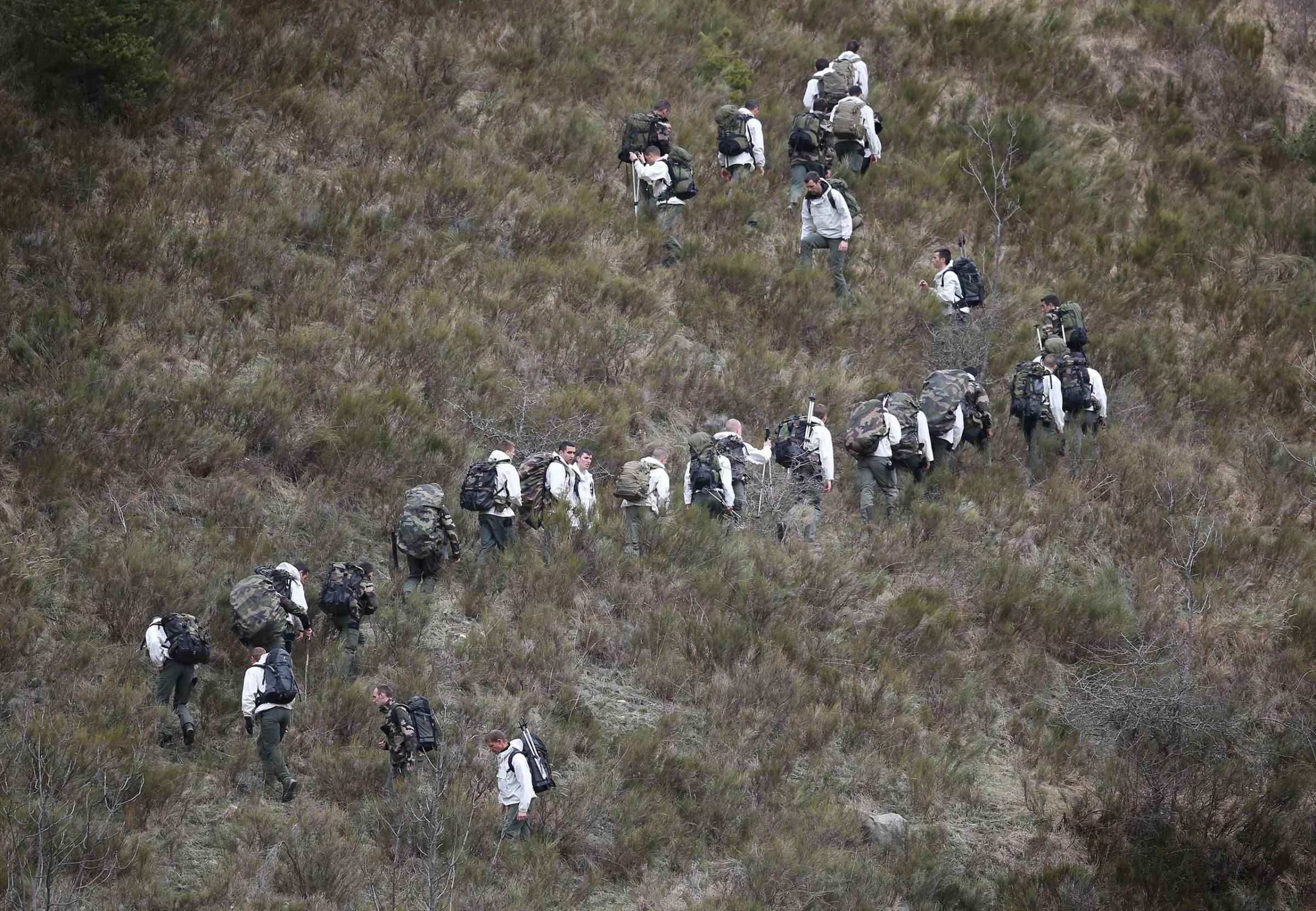

Witness Scenes From the Plane Crash in the French Alps

And pilots aren’t likely to divulge any potential mental health problems, including signs of depression or anxiety, because that would take them out of the sky. “Pilots aren’t going to tell you anything, any more than a medical doctor would about their mental health,” says Scott Shappell, professor of the Human Factors Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautics University who is a former pilot and crash scene investigator.

Pilots, like doctors and policemen and others with high-stress jobs, tend to be good at compartmentalizing — walling off difficult or emotional experiences so they don’t interfere with their ability to function day-to-day. Medical examiners who evaluate pilots for their recertification also aren’t always trained in mental health, so they may not recognize subtle signs of conditions such as depression or alcoholism.

According to Dr. William Sledge, medical director of the Yale-New Haven Psychiatric Hospital who has evaluated pilots for the Federal Aviation Administration, about 40% of pilots he saw were for alcohol related problems, and a third for depression or anxiety. Only about half of the latter group reported their problems themselves, however. The other half were referred to Sledge only after incidents required their superiors to intervene.

“The problem is there is no incentive” to report mental health issues, says Shappell. “They know that if they self report, the way the system is designed, it will be a black mark.”

In a statement, the FAA said: “Pilots must disclose all existing physical and psychological conditions and medications or face significant fines of up to $250,000 if they are found to have falsified information.”

In the case of mental health evaluations, pilots are taken off the flight schedule while they are treated or begin antidepressant medications. Until 2010, even these drugs were banned, and pilots required them could no longer fly.

When the U.S. Air Force began requiring annual suicide prevention and awareness training in 1995, including screening for mental illness, the suicide rate plummeted from about 16 suicides per 100,000 members to about 9.

Even for experts, however, judging whether a pilot is suicidal is one of the hardest parts of the job. That’s no surprise, since the struggles of spotting and talking about suicide plague our entire society, says Barbara Van Dahlen, a licensed clinical psychologist and the founder and president of Give an Hour, a network of volunteer therapists. “In our society we are so quick to try to make it ok, to say it will pass and to say suck it up,” she says. “We really don’t listen to ourselves and we don’t listen to others very effectively.”

But pilots and others in high-pressure occupations face several unique stressors, she says, like having a physically demanding job and being responsible for other lives. “In a lot of positions of authority and leadership, those people are supposed to be capable and on top of things,” she says. “They don’t have a lot of people to share with and talk to, to be less than perfect and less than OK. That adds to the stress.”

One study of suicides among general aviation pilots—civilians who aren’t leading scheduled commercial flights—published in the journal Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine, looked at 21-years’ worth of general aviation accidents as reported by the National Transportation Safety Board between 1983-2003. During that time, 37 pilots either committed or attempted suicide by aircraft, and nearly all resulted in a fatality. 38% of the pilots had psychiatric problems, 40% of the suicides or attempts were linked to legal troubles, and almost half, 46%, were linked to domestic and social problems. 24% of the cases involved alcohol and 14% involved illicit drugs.

Having ready access to a plane also seemed to be a contributing factor, too; 24% of the crashed planes in the study were used illicitly.

Read next: German Pilots Cast Doubt on Blaming of Co-Pilot for Crash

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com