The order from the war department came on this day, March 19, in 1941: a new Pursuit Squadron and Air Base Detachment was to be formed in Illinois, eventually to be based in Tuskegee, Ala.

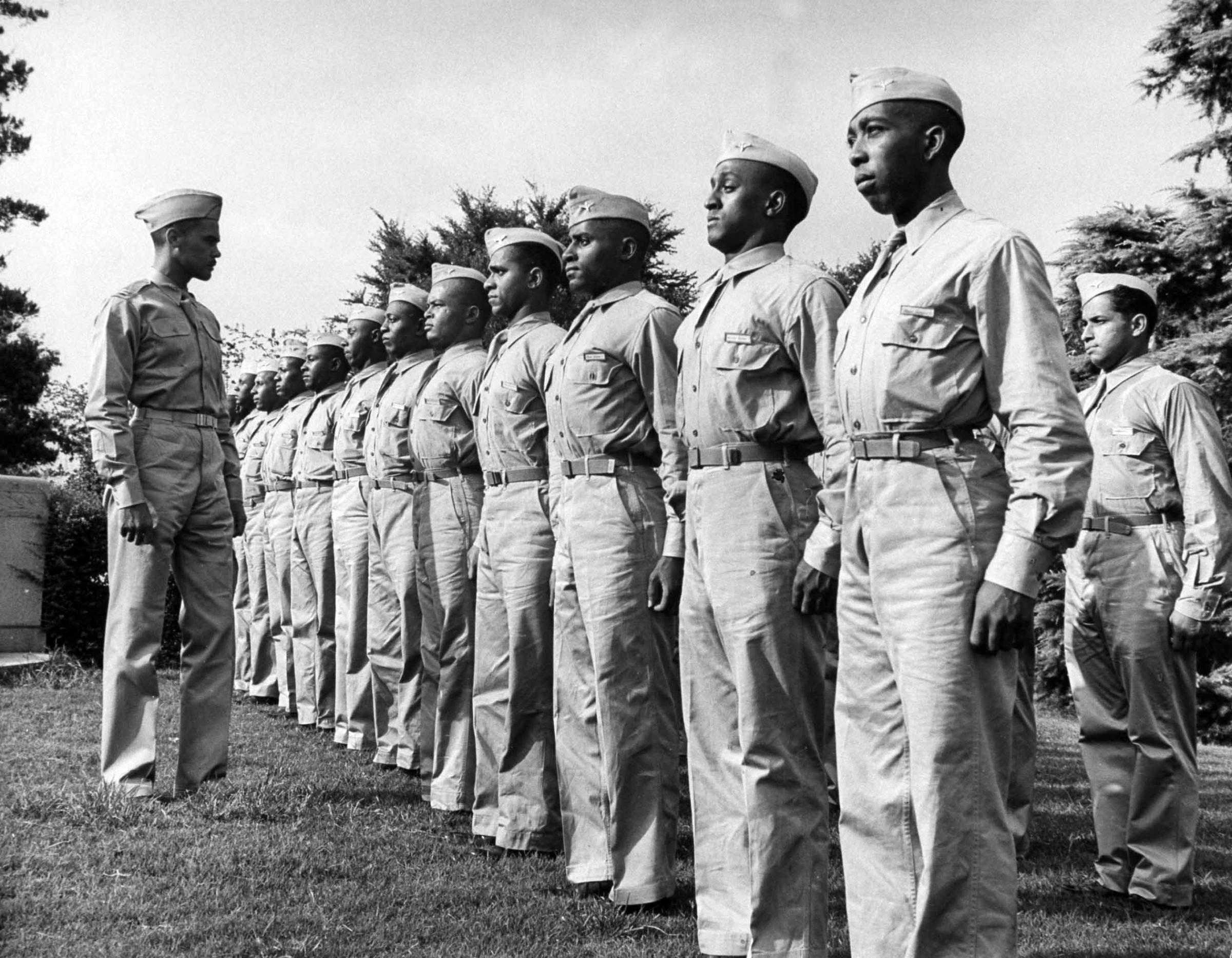

Though the order never mentioned race, that squadron had a very special place in the history of the integration of the U.S. Armed Forces. By September of 1941, TIME commented that the Tuskegee Institute was home to “something new in the world”: “All twelve of the gray-clad cadets and the one slim young officer student were Negroes, charter members of the Air Forces’ 99th (all Negro) Pursuit Squadron, soon to become the first Negro flying officers of the U.S. Army. ”

But the existence of the Squadron, and those Tuskegee-based groups that followed, known collectively as the Tuskegee Airmen, was entirely welcomed by supporters of racial equality. Though the group integrated the ranks of military pilots, it was in a segregated manner. The question of integrating the Armed Forces was hardly a new one in 1941, but hopes had been high that the exigencies of World War II would hurry the answer along.

In the fall of 1940, President Roosevelt dashed those hopes by announcing that military training in the Army would be separate but equal. In fact, TIME’s first-ever acknowledgement of the Tuskegee Airmen was headlined “As Jim Crow Flies.” In 1942, the magazine commented that the situation for the pilots “might have exasperated Job”: that they were accused by some of betraying those who urged real integration, while others thought the Armed Forces had gone too far already.

“A white planter [from near the base] telephoned that he would kill the first Negro soldier who ever again waved greetings to his womenfolk,” TIME reported. “An officer called a meeting of white farmers, told them that this is just what Hitler wanted, just this kind of division among the U.S. people; Goebbels would be delighted.”

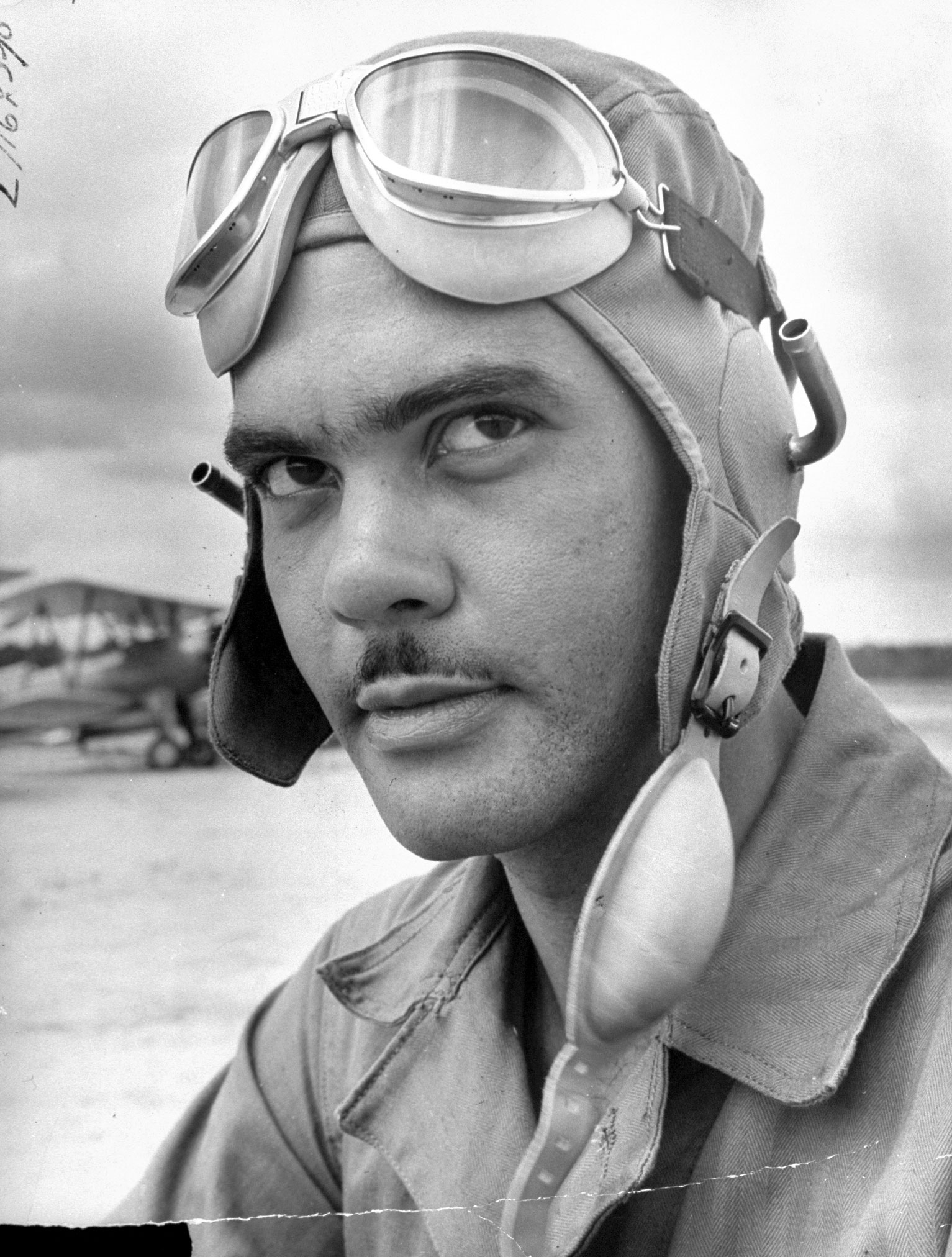

But when it came to the problems of actually becoming pilots, however, the men of the Squadron were well-prepared, according to a description from that year:

Tuskegee‘s Negroes faced two problems: 1) learning to fly; 2) learning to become aggressive, when every tradition had taught them submissiveness. The raw material was good. Of these Negro cadets, 57% had had technical studies in school, the average had had three and a half years of college. Of the first 81 cadets accepted, 44 were from the South, 26 from the North, six from the Middle West, five from the Far West. They were anxious, eager, studied hard, flew hard, busted buttons bulging their chests at inspection.

Read the full 1942 story, here in the TIME Vault: The Ninety-Ninth Squadron

When the Tuskegee Airmen Got Their Wings

![Booker T. Washington [Misc.];Benjamin O. Jr. Davis Past statue of Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute, march the vanguard of 400 negro fliers who will eventually compose the Army's 99th Pursuit Squadron. Their base will be one of nation's top squadron fields.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/150209-tuskegee-airmen-06.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com