If the thought of the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list fills your head with visions of hardened prisoners with long rap sheets, you’re not alone. Since March 14, 1950, the list has led to the capture of 156 criminals—and captured the American imagination along with it. But the story of how law enforcement started its iconic list involves more than mere post offices and police stations. It’s a romp across American history that involves the printing press, the Wild West, Prohibition and the evolution of the news as we know it.

In a time before walkie-talkies, cell phones and high-tech surveillance, nabbing criminals relied on good old-fashioned detective work. But detectives have always needed citizens to feed them relevant information and help them track down suspects.

Long before America was even a country, precursors of “wanted” posters, made possible by printing technology, were used to help track down scofflaws and apprehend criminals. Runaway slaves, not exactly the kind of criminal we’d think of today, were among the first to be targeted by the new mass media. In 1769, a young man named Thomas Jefferson—yes, that Thomas Jefferson—took to The Virginia Gazette to offer 40 shillings for the safe return of Sandy, a slave he described as “inclining to corpulence, and his complexion light.” His use of the newspaper was typical of slave-owners who shared details about runaways’ names, appearances and potential whereabouts in an attempt to reclaim their property.

As printing and photography evolved, so did wanted posters. Frontier sheriffs and governors created compelling posters advertising bounties and spreading the word about outlaws like Jesse James and Butch Cassidy. (According to one such poster, Jesse James was worth a cool $5,000 if arrested and another $5,000 if convicted—the equivalent of over $113,000 in today’s dollars.)

By 1919, the FBI started issuing its own wanted posters for military deserters and gangsters. That same year, a civic watchdog group called the Chicago Crime Commission formed in response to a surge of organized crime in the Windy City. In April 1930, the Commission released a list of “public enemies” headed up by Al Capone. Intrigued by Chicago’s most notorious Prohibition-era criminals, reporters took note and the list took off. The popularity of lists was just as true back then as it is today.

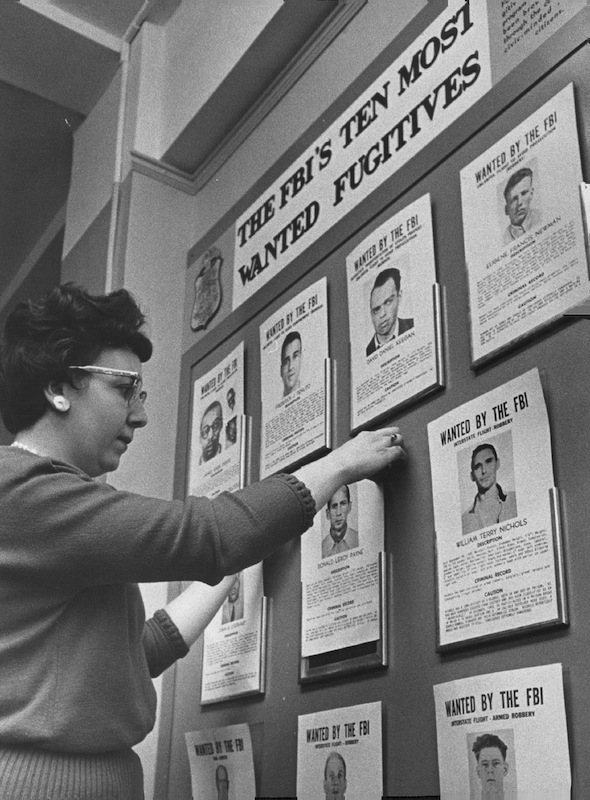

This got the attention of Bureau of Investigation and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. TIME noted in 1939 that the FBI “usually considers it undesirable to dignify Public Enemies by listing them,” but that the agency sometimes did so anyway. (At the time of that article, bank robber Irving Charles Chapman was at the top of the FBI’s unofficial list.) Unsurprisingly then, when Hoover was approached by a reporter for the International News Service (now United Press International) and asked about the “ten toughest guys” he wanted to capture in 1949, Hoover seized the opportunity to spread the word about America’s most dangerous criminals. The article that resulted was so popular that he decided to make it a regular program, and on March 14, 1950, the FBI issued its first official “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list.

Number one on the list was Thomas James Holden, a bank robber whose rap sheet included charges of robbing a mail train, escaping prison and murdering his wife. Less than a year later, Holden was apprehended after being recognized by an acquaintance in Oregon who had seen the top-ten list in a local newspaper. And nabbing fugitive number one was just the first of the list’s many successes. Boosted by media, beloved by sharp-eyed citizens and helped along by a healthy reward program, the list still endures 65 years later.

FBI agents don’t always get their man; they’re still hunting, for example, for Victor Manuel Garena, a bank robber who has been on the list for more than 30 years. But other fugitives aren’t so lucky: In 1969, Billie Austin Bryant became one of the list’s shortest-ever occupants. He occupied a slot in the top ten for a mere two hours before he was discovered by a citizen in a Washington, D.C. attic and arrested.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com