On the last Saturday of every February, sword swallowers gather at Ripley’s Believe It or Not museums throughout America to commemorate World Sword Swallower’s Day. It’s a sideshow so dangerous there are only a few dozen full-time professionals, according to trade association Sword Swallowers Association International (SSAI). The society claims sword swallowing takes 3-10 years to learn, though some say they mastered it in six months. We talked to five professionals about how it’s done and how it has almost killed them.

Beginners practice using wire coat hangers.

“Most people start with a coat hanger stretched out in the outline of a sword,” says Todd Robbins, 56, a sword swallower who has lectured about the history of sideshows at Yale. Beginners also use paint brushes, spoons and knitting needles to desensitize their gag reflexes.

Here’s how Dan Meyer, 57, Tampa, Fla.-based SSAI president and former America’s Got Talent contestant whose personal record for swords swallowed is 21, describes the technique at an American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting:

“When I put the sword in my mouth, I will repress the gag reflex in the back of the throat. Then I have to go behind my Adam’s apple, my prominentia laryngea, behind the voice box, the larynx, down about through the crichopharyngeal sphincter, up in the upper part of the mouth here. Then down into the esophagus, repress the peristalsis reflex, [muscular contractions] that swallow your food. From there relax the esophageal muscles, relax the lower esophageal sphincter, and slip the blade down into my stomach, repress the wretch reflex in my stomach.”

Below is an X-ray of Meyer swallowing one at Vanderbilt Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., on Feb. 5, 2013, for a Discovery Channel Canada show:

You can thank sword swallowers for the endoscope.

Dr. Adolph Kussmaul is said to have used a sword swallower to develop the rigid endoscope, a medical device with a light and a camera that often travels through a patient’s throat, in 1868.

Turns out non-surgical procedures are a breeze for people like Robbins, who says, “I had to have an endoscopy done, and normally they knock the person out and have to intubate them, but since I was a sword swallower, [the doctor] just handed [the endoscope] to me.”

Sore throats are a common side effect.

So says a 2006 study of 46 sword swallowers (40 men) published in the British Medical Journal, which found dire injuries like intestinal bleeding, perforations to the pharynx and esophageal lacerations are more likely to plague performers with elaborate routines, too many consecutive shows or who use multiple swords, especially unusually-shaped ones. Co-written by Meyer and British radiologist Brian Whitcombe, it won an Ig Nobel Prize, awarded annually by the Annals of Improbable Research magazine at Harvard University for especially imaginative scientific achievements. (Meyer accepted the award at the university’s Sanders Theatre and then swallowed a sword on stage.)

Case in point, Meyer punctured his esophagus after setting a world record for swallowing two swords simultaneously underwater and once punctured his stomach swallowing five swords, which caused fluid build-up around his heart and lungs. Robbins once had a neon sword, which lights up the chest, break inside of him. And Natasha Veruschka, a belly-dancing sword swallower in New York City, says she chugged heavy cream and rum to soothe her throat after she accidentally swallowed a sword covered with little barbs that made it painful to remove.

The “oldest, longest performing” sword swallower is said to be 79.

Unlike the aforementioned performers, Jim Ball of Oakley, Kansas, says he has avoided life-threatening injuries by sticking to a “kind of conservative” routine, swallowing a Japanese samurai sword about once a month (though throughout his life, he has swallowed bayonets, cavalry sabers, and a stove poker). Raised by parents who were professional sword swallowers, he entertained fellow Army soldiers by swallowing rifle cleaning rods. If you’re wondering what it’s like to swallow a sword, especially for the first time, he says, “it feels like accidentally swallowing a piece of ice.” Nowadays, he’s teaching his college-age granddaughter how to do it.

Some started doing it to overcome childhood demons.

While Ball, Robbins and Veruschka learned sword swallowing from growing up around sideshow performers or seeking them out at shows, Meyer described his younger self as a “shy wimpy kid” with “social anxiety,” often picked on by bullies, who tried sword swallowing after a near-death experience with malaria inspired him to take risks and fear nothing. New York-based freelance writer Ilise Carter, 40, whose stage name is “The Lady Aye” says when she learned, “I was a recovering bulimic, but I eventually decided the only way to combat your fear is to go straight through it. You [develop] a great connection to your body, and the audience’s positive reaction has made me a much stronger person in general.”

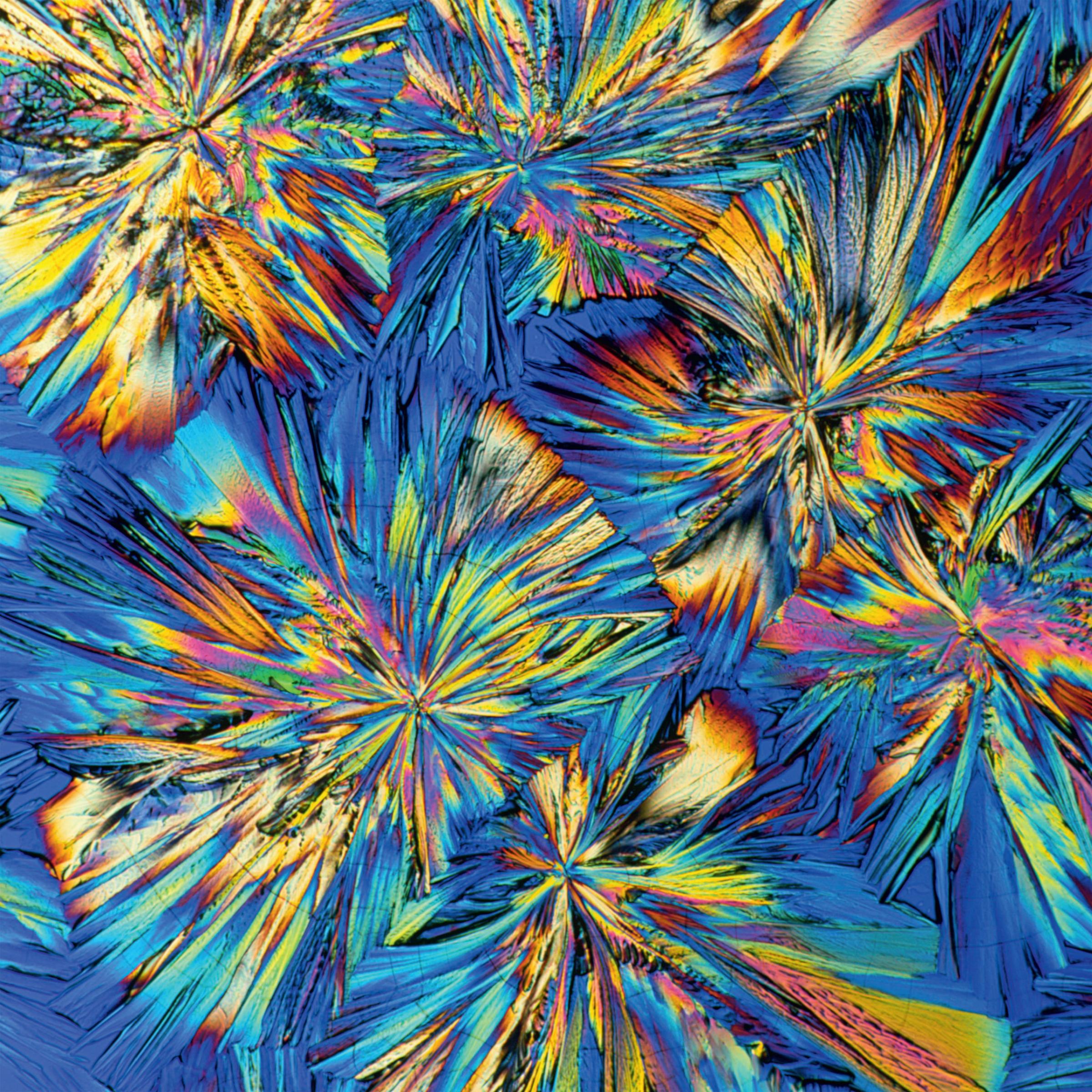

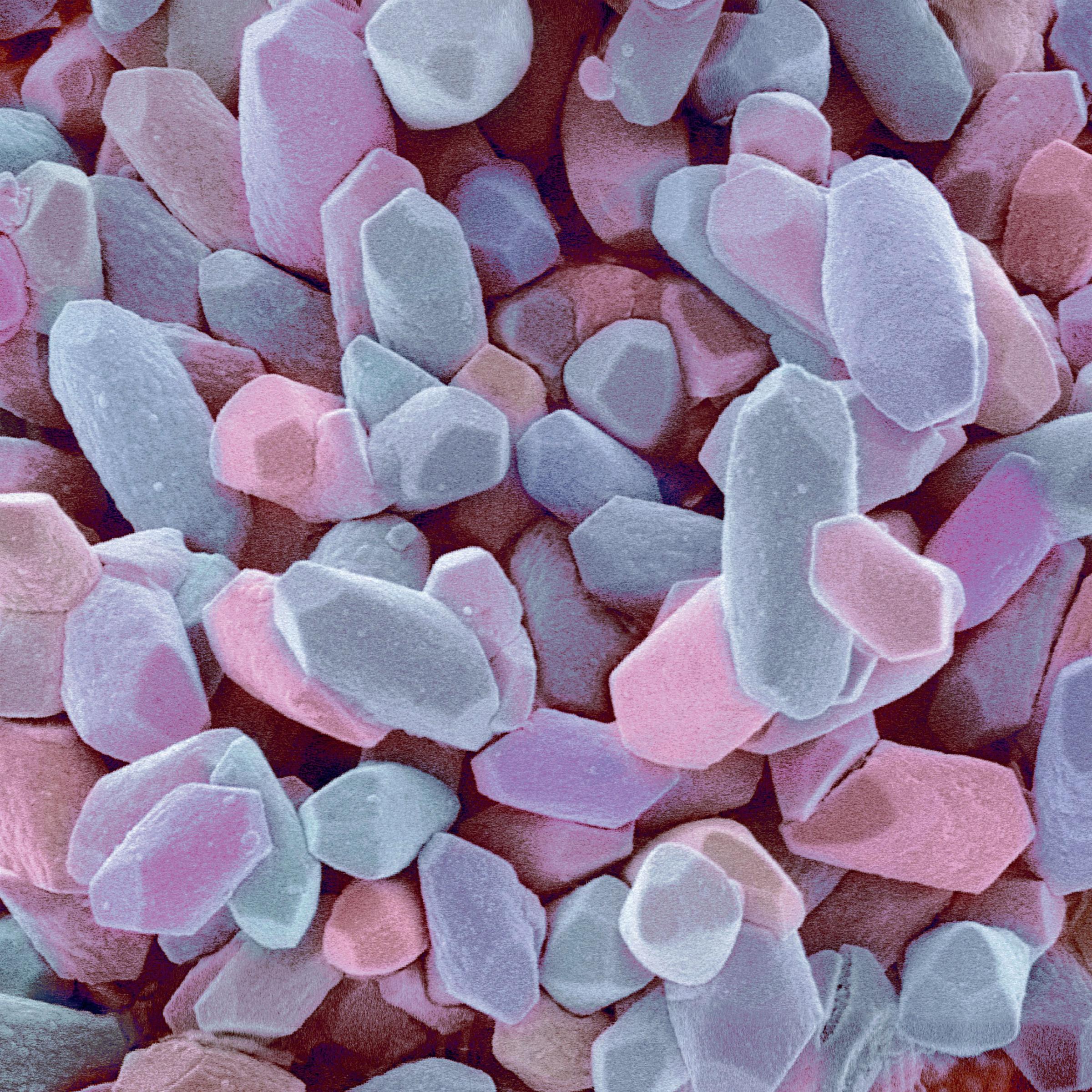

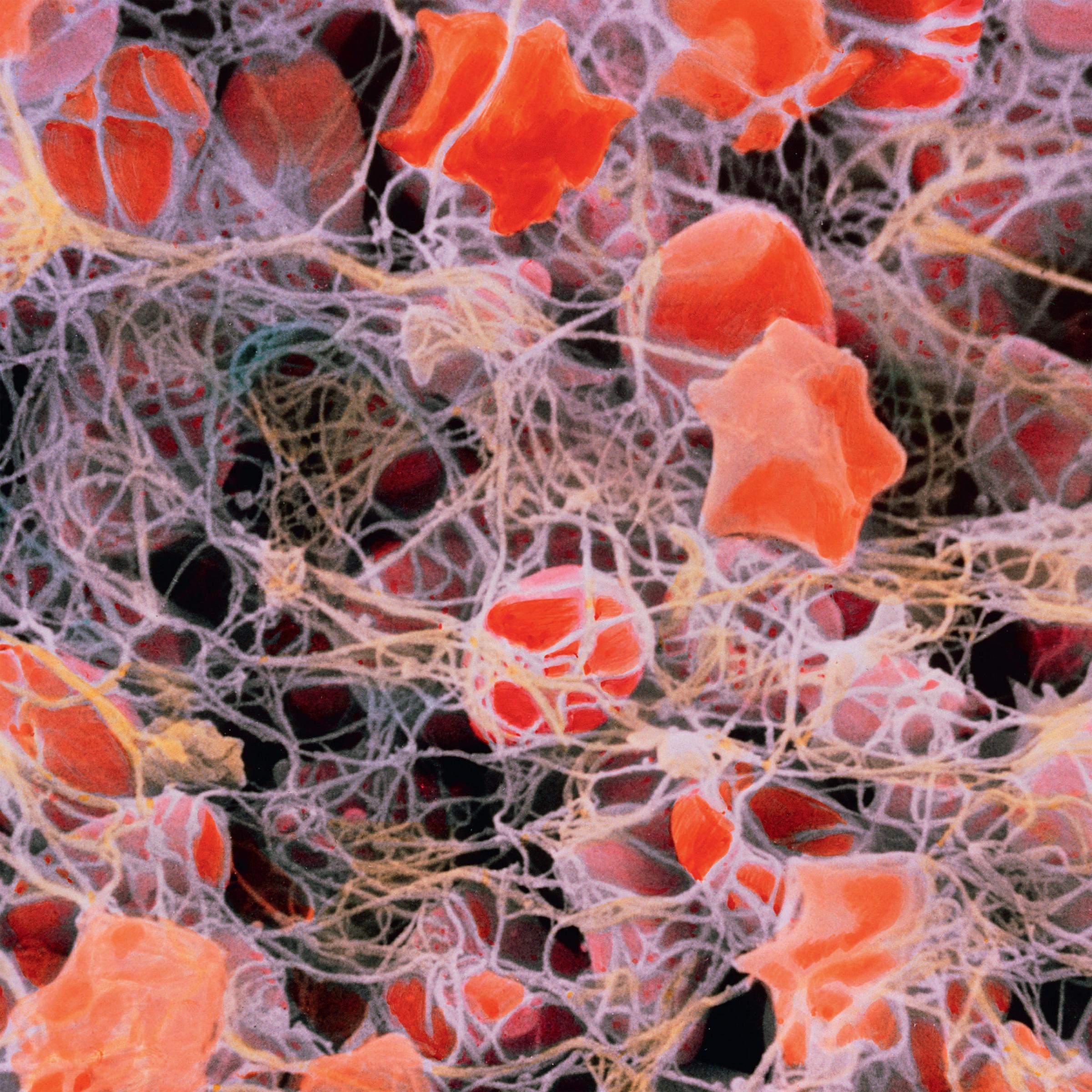

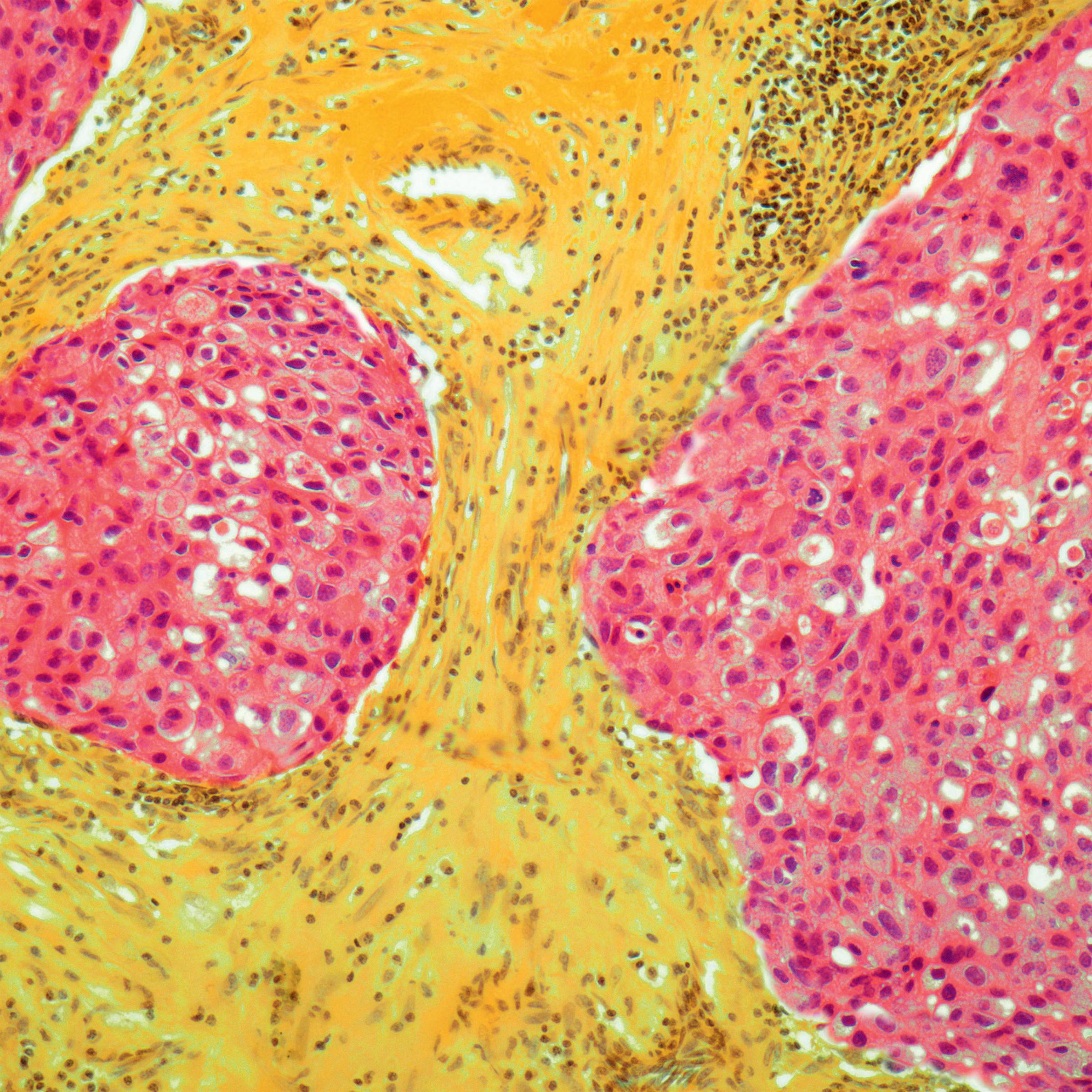

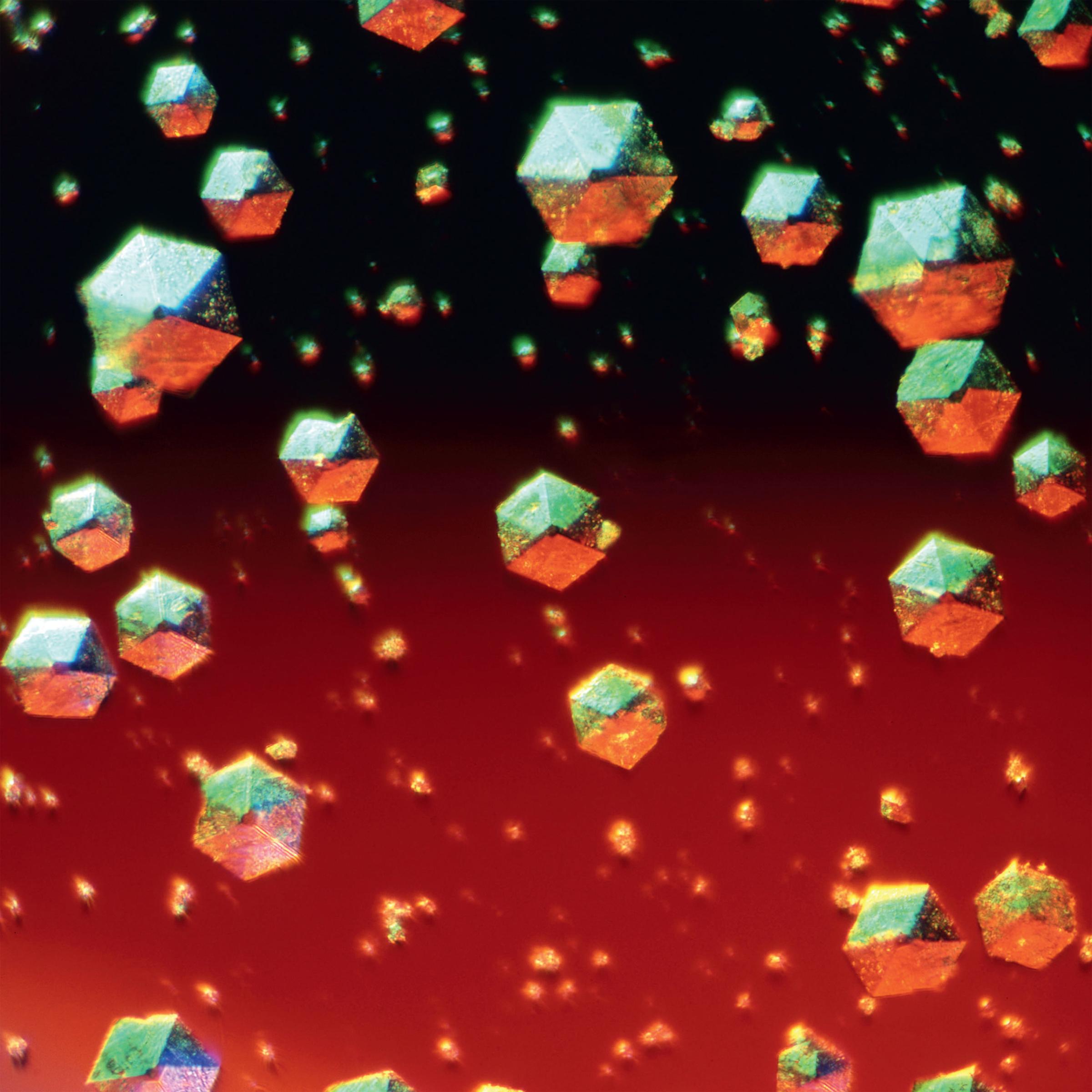

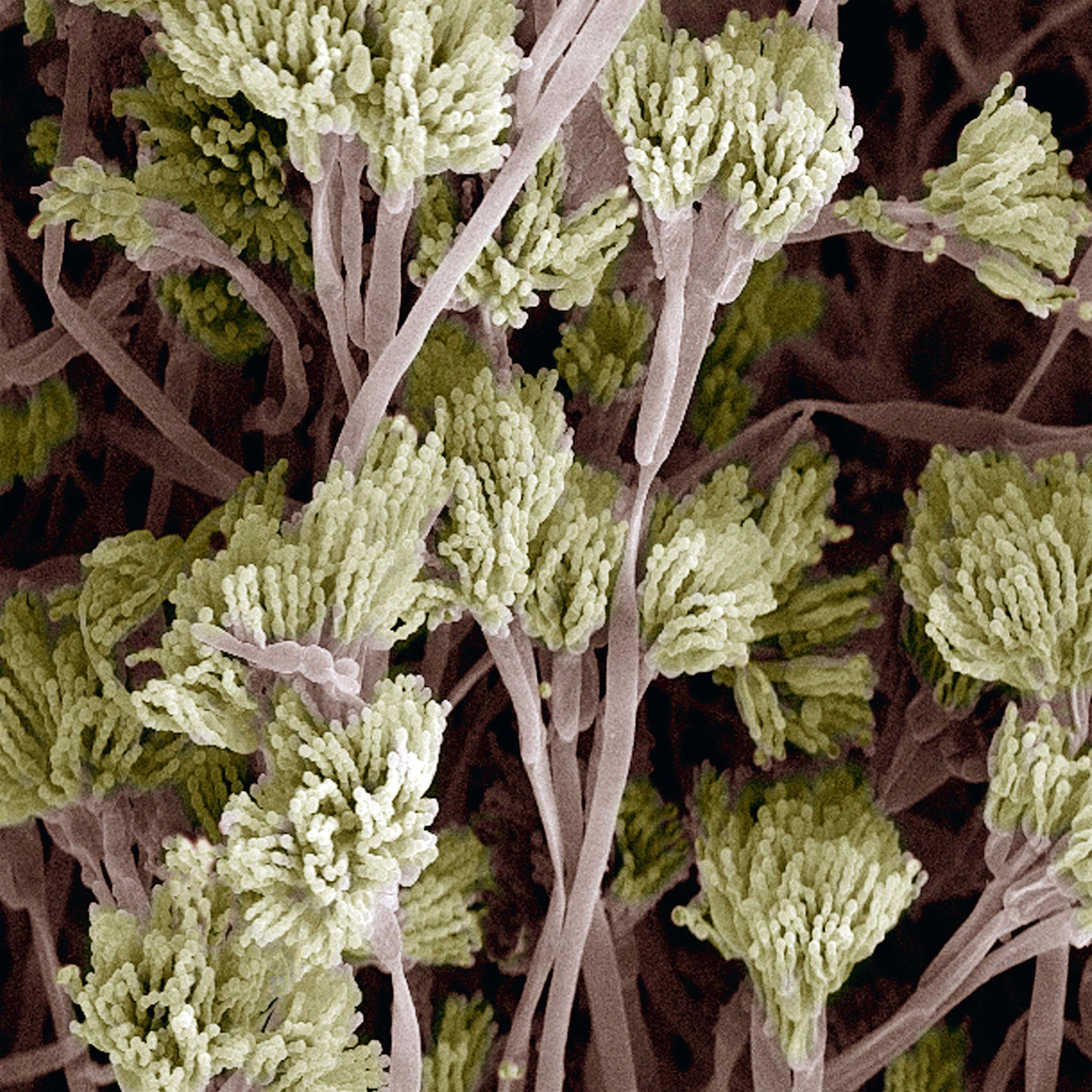

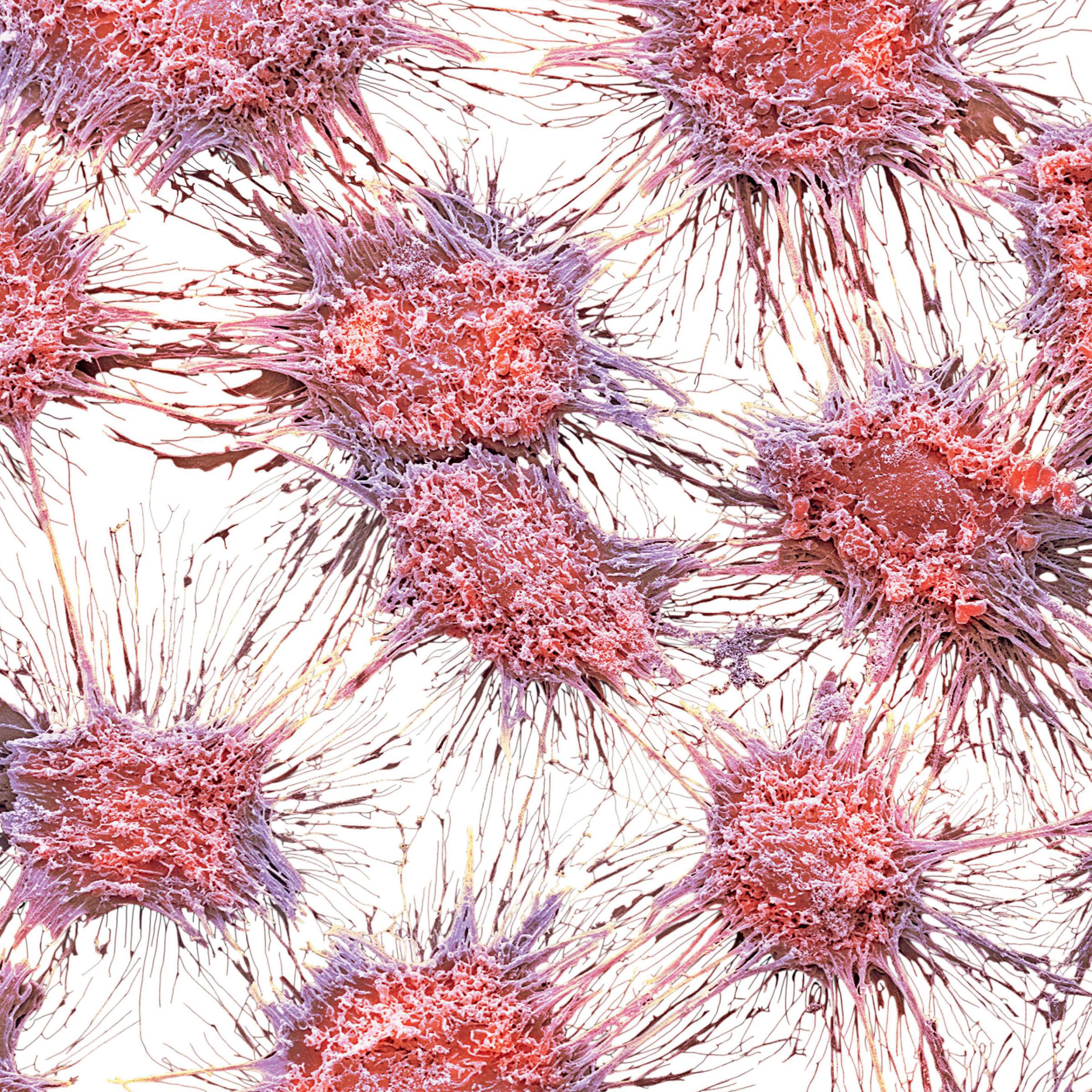

See the Human Body Under a Microscope

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com