Along southern Florida’s Muck City Road, southeast of the state’s massive Lake Okeechobee and hidden among hundreds of acres of sugar cane, sits Miracle Village, pop: approximately 150.

For decades, its tiny one-story residences housed migrants who worked the nearby sugar fields. Today, they house migrants of a different sort. Most of its residents are convicted sex offenders.

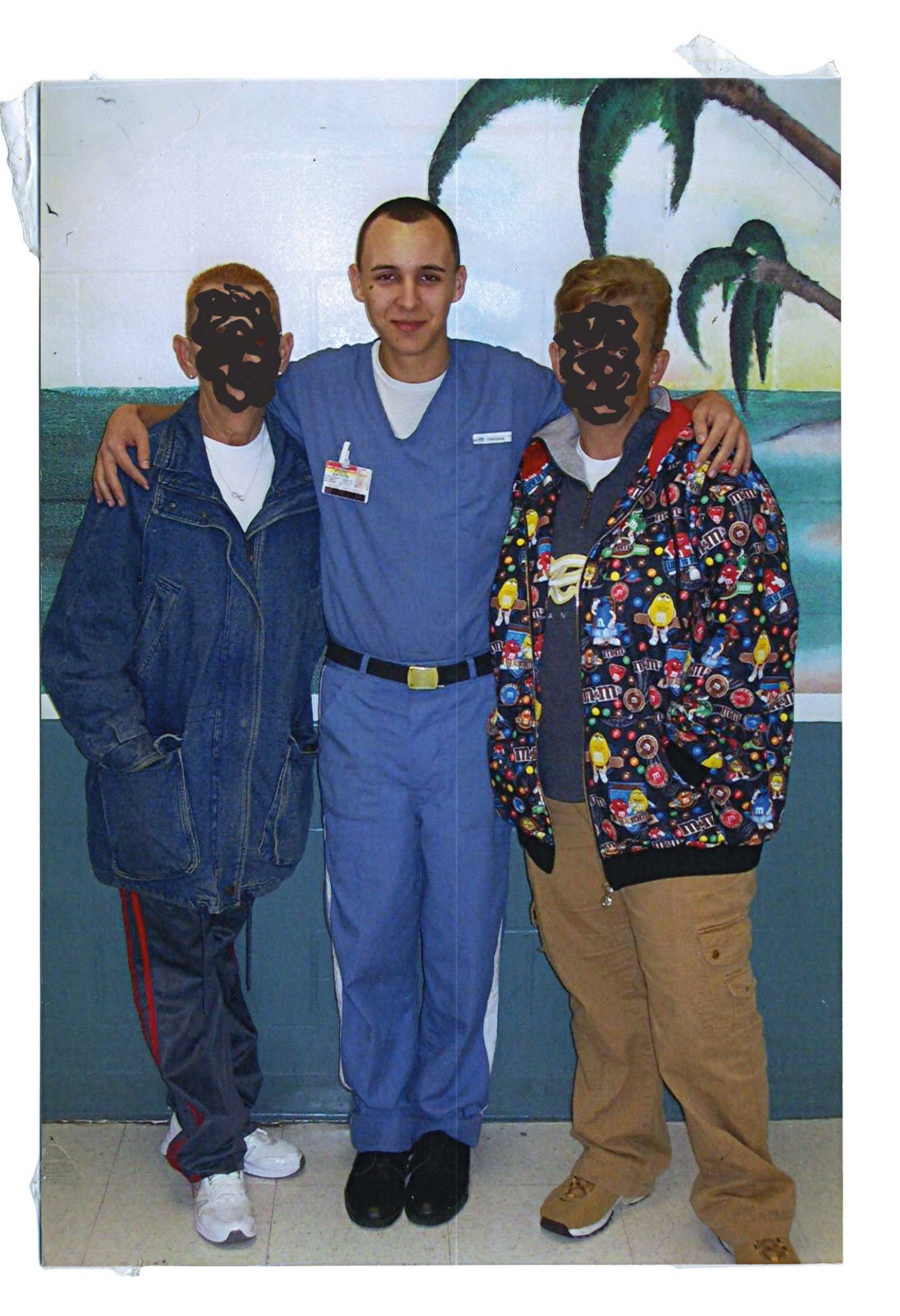

Sofia Valiente, a 24-year-old photographer and a resident of Florida since she was 10, began visiting the community in January 2013, spending a total of three months there and even living in the residential complex for several weeks. The result is Miracle Village, a book produced and published by Benetton’s communication research center Fabrica that profiles the community’s residents preparing for work, interacting alongside family members and dealing with the daily restrictions that limit virtually everything they do, from their Internet use to when they can be outside.

There are almost 800,000 federally registered sex offenders in the U.S. That registry originated in the 1990s when Congress passed legislation that severely targeted those who commit violent crimes and crimes against children. But states have their own varying laws, Florida’s being some of the most stringent. Sexual offenders in the state must notify public officials whenever they move; they’re subject to a 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew; and they can’t live within at least 1,000 feet of a school, day care center, park, playground or any other place where children often gather. Those restrictions, many victims’ families argue, are necessary to prevent sex offenders from engaging in further criminal activity.

Cities and counties oftentimes have their own laws, some more stringent than others. Curfew for some in Miracle Village is 7 p.m. Many residents have to wear GPS-monitored ankle bracelets that keep tabs on them at all times. They can’t interact with minors, even if they’re family. They’re subject to random drug tests. Some can’t use the Internet. Others can’t own a smartphone.

A more pressing difficulty, however, is often finding a place to live. In some counties in Florida, sex offenders are banned from being within 3,000 feet of places where children congregate, making living in most towns and cities virtually impossible.

In 2009, Dick Witherow, a local evangelical pastor, founded Miracle Village as a sort of haven for area sex offenders struggling to find housing. The village is not only physically removed from populated areas—it’s surrounded by hundreds of acres of sugar cane and is located several miles from nearby Pahokee—but Witherow’s ministry, Matthew 25, also provides support for those living there and interviews other sex offenders looking to relocate to determine if they’d be a good fit for the community.

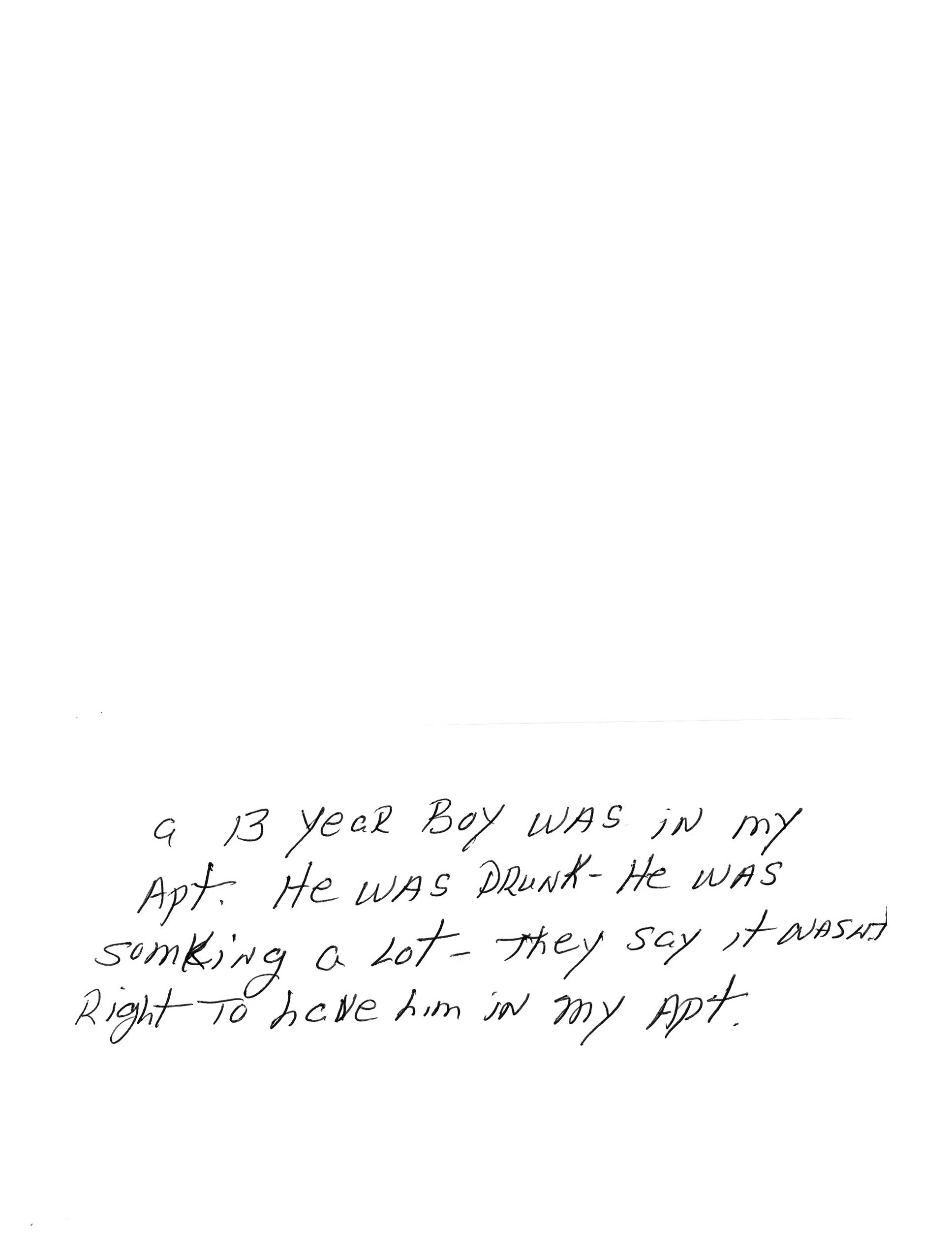

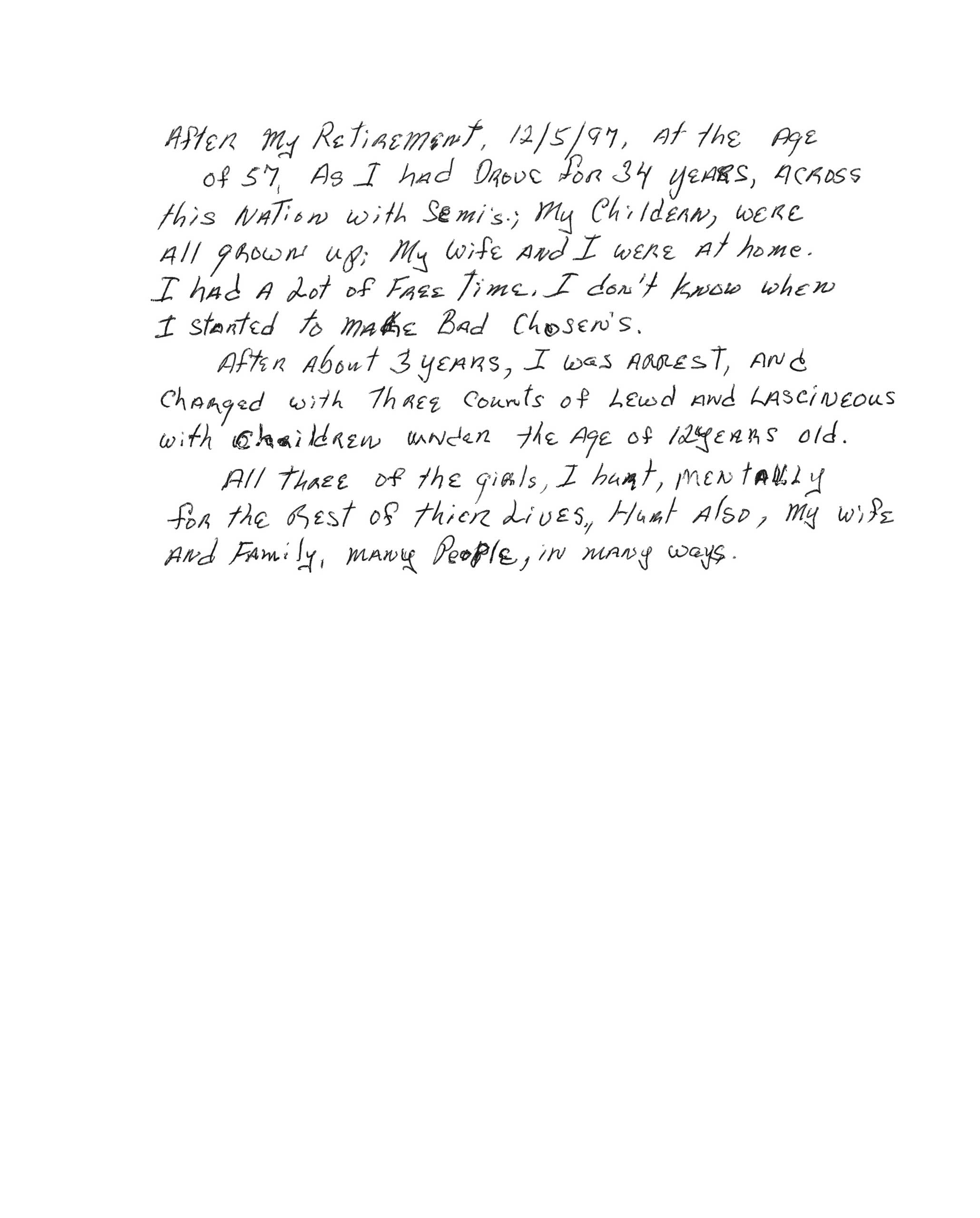

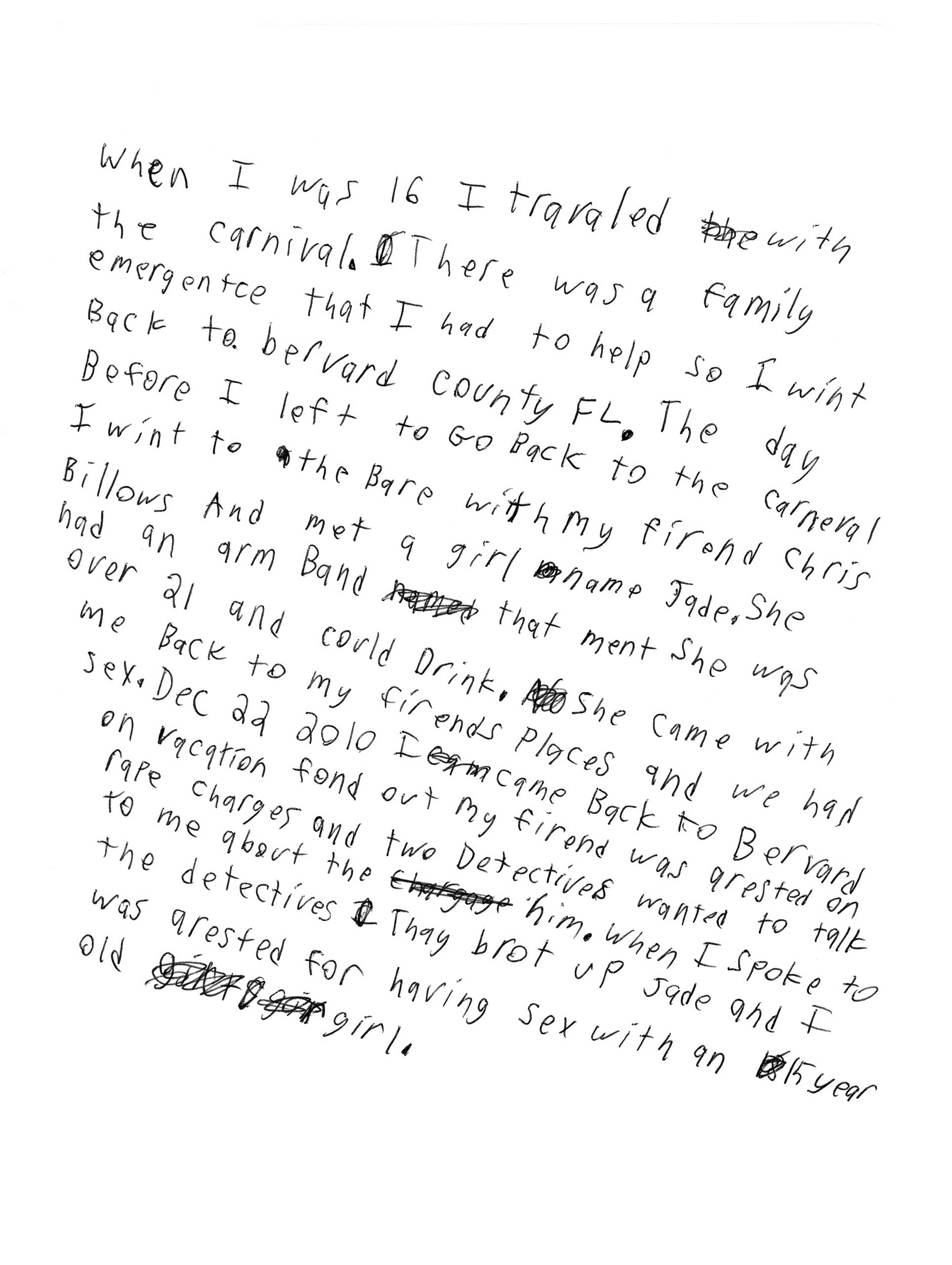

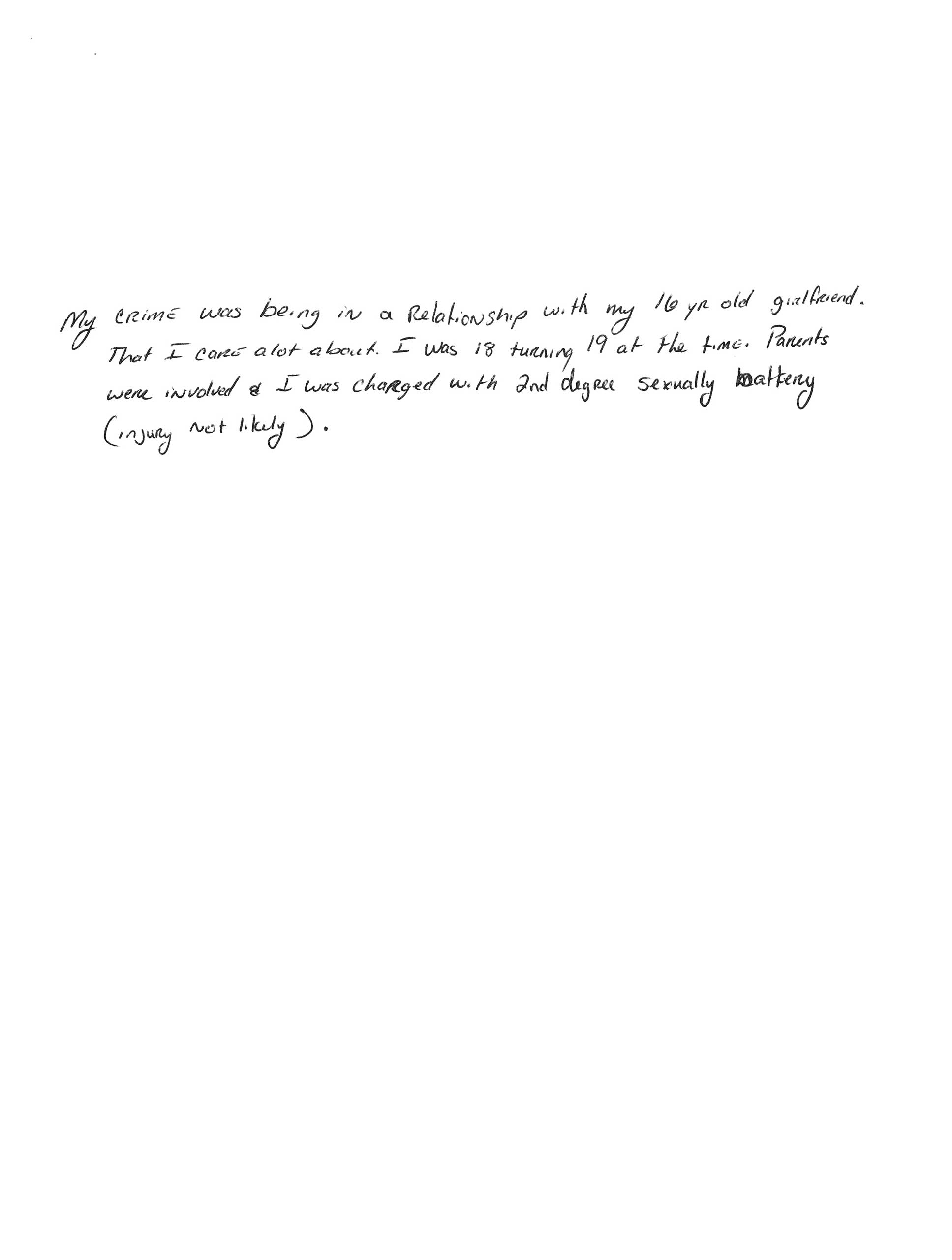

Valiente’s photos of the village’s members are subtle and are oftentimes straight-on portraits, an aesthetic that takes on the look of traditional documentary photographs. She also had many of the community’s residents write letters describing their past crimes.

“I had sex with my younger brother,” writes Matt, one Miracle Village resident.

“My crime was being in a relationship with my 16 yr old girlfriend. That I care a lot about,” writes David. “I was 18 turning 19 at the time. Parents were involved & I was charged with 2nd degree sexually battery (injury not likely).”

“I married a man that abused me,” writes Rose. “He did drugs and drank until he passed out. He told me that I was never going to leave him with our children. The course of events that led up to me being arrested is too long of a story and very painful for me to speak about in detail. I was arrested & charged of molesting my children.”

Valiente says her goal with Miracle Village was to portray the community’s residents in a way most people have never seen.

“I try not to address what is right and what is wrong. I can’t look at it that way. This is more about confronting the stigma,” Valiente says. “They would be lepers in society. Here, they’re not lepers.”

Sofia Valiente is a fine art photographer based in South Florida. Miracle Village is published by Fabrica.

Josh Sanburn is a writer/reporter for TIME in New York. Follow him on Twitter @joshsanburn

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com