“Absurd.” That’s how documentary photographer Mathias Depardon describes the surreal scene of a mosque’s minaret jutting out from the water as a boat passes by in Savaçan.

The tiny community along the Euphrates River in the predominantly Kurdish southeastern region was flooded by the filling of the Birecik Dam’s reservoir about 15 years ago, pushing its residents and others nearby into a new settlement erected by the country’s housing authority.

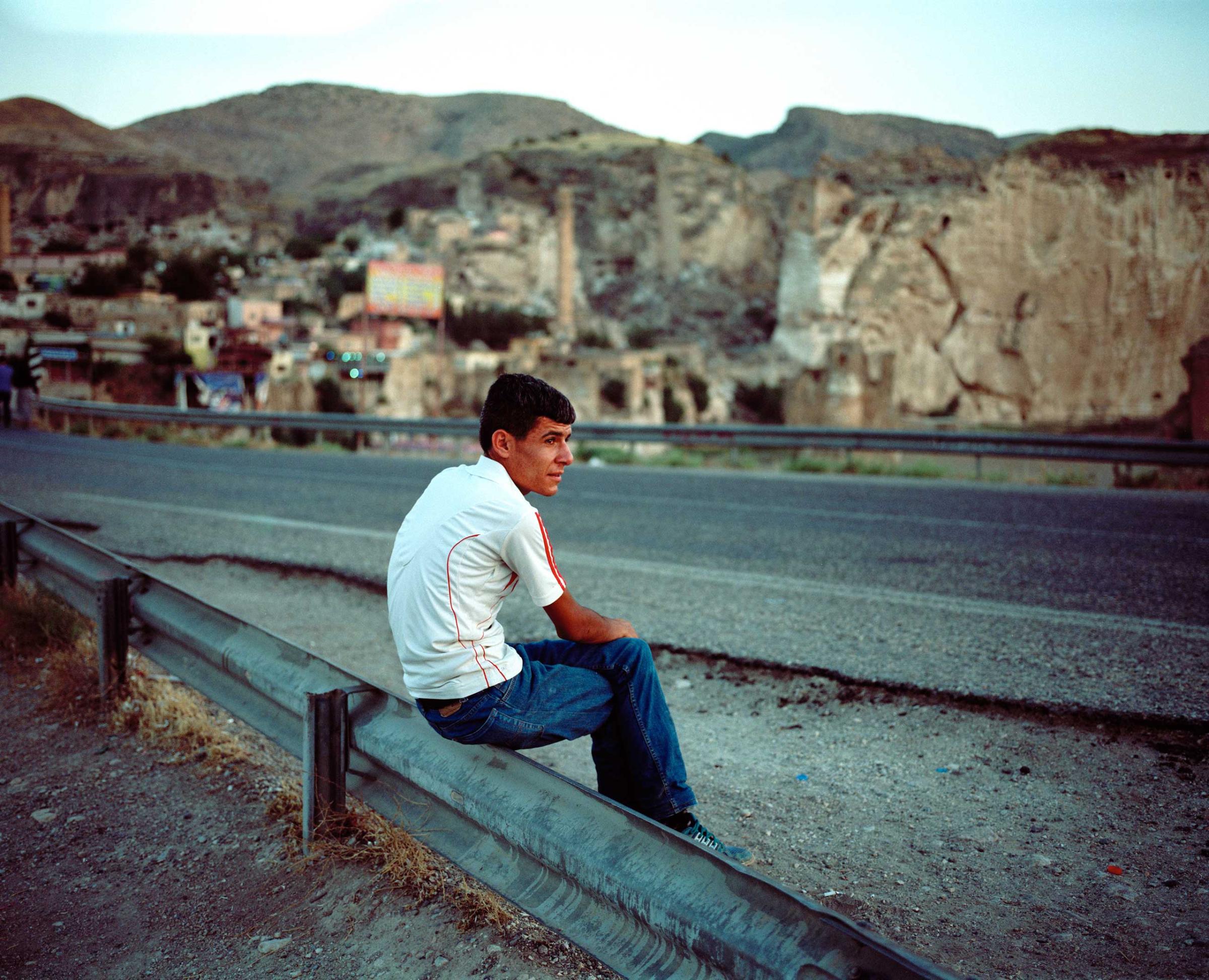

Activists worry Hasankeyf is next. The small village with ancient roots on the edge of the Tigris River is upstream from the hydroelectric Ilisu Dam, the last major dam to be built within the decades-long Southeastern Anatolia Project, Turkey’s largest hydropower project that is comprised of 22 dams and 19 power stations. Once construction on Ilisu is done—Turkey was forced to secure alternative funds after European backers pulled out, putting it behind schedule as environmental campaigns steadily lobbied against it—the filling of an 11 billion cubic-meter reservoir will inundate some 74,000 acres, including Hasankeyf.

Ankara has long-positioned the dam as a provider of irrigation and jobs to an impoverished corner of Turkey, and considers it part of the solution to the country’s dependence on foreign energy imports amid increasing domestic demand, as the dam is expected to generate some 2% of Turkey’s current electricity supply. The tradeoff, aside from the further of squeezing crucial supplies downstream in Syria and Iraq, exacerbating already strained tensions from decades of cross-border water disputes, is that part of Hasankeyf—along with its found and still hidden archaeological treasures—and other nearby sites will morph from open air exhibits on ancient Mesopotamia to underwater treasure chests. (Hasankeyf was placed on the World Monuments Fund’s 2008 Watch List.)

Turkey says archaeologists are working to excavate, record and preserve “as much as possible.” And, like others impacted by dams, residents due to be displaced by water can move into a new settlement built across the river.

Depardon, who is half-French and half-Belgian, heard about the project after he moved to Turkey a few years ago. For the 34-year-old photographer, who estimates that he shoots 30 to 50 assignments in a given year, the disappearing village became part of his personal project: an environmental portrait of a land steeped in history before it’s drowned.

A lot of people have assumptions about what Hasankeyf will be like, he says, especially in light to what happened to Savaçan: “People don’t go [to Savaçan] with the nostalgia of the place. Obviously, they didn’t know the place before that, they’d never been there. But they go there and they visit as they would an entertainment park.” Still, he adds, not everyone in the area is against the dam.

Hasankeyf is the iconic at-risk community, Depardon says, but his project is more of a visual look at overall Turkish dam policy that’s driven, he says, by anti-environmental policymakers in Ankara. That’s part of why he named the project Gold Rivers. The expected completion of the dam this year, and the energy that it will help generate, will help pad state coffers while impacting local tourism industries: “The water is now money.”

Mathias Depardon is a documentary photographer based in Istanbul, Turkey. Follow him on Instagram @mathiasdepardon.

Mikko Takkunen, who edited this photo essay, is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @photojournalism.

Andrew Katz is a News Editor at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @katz.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com