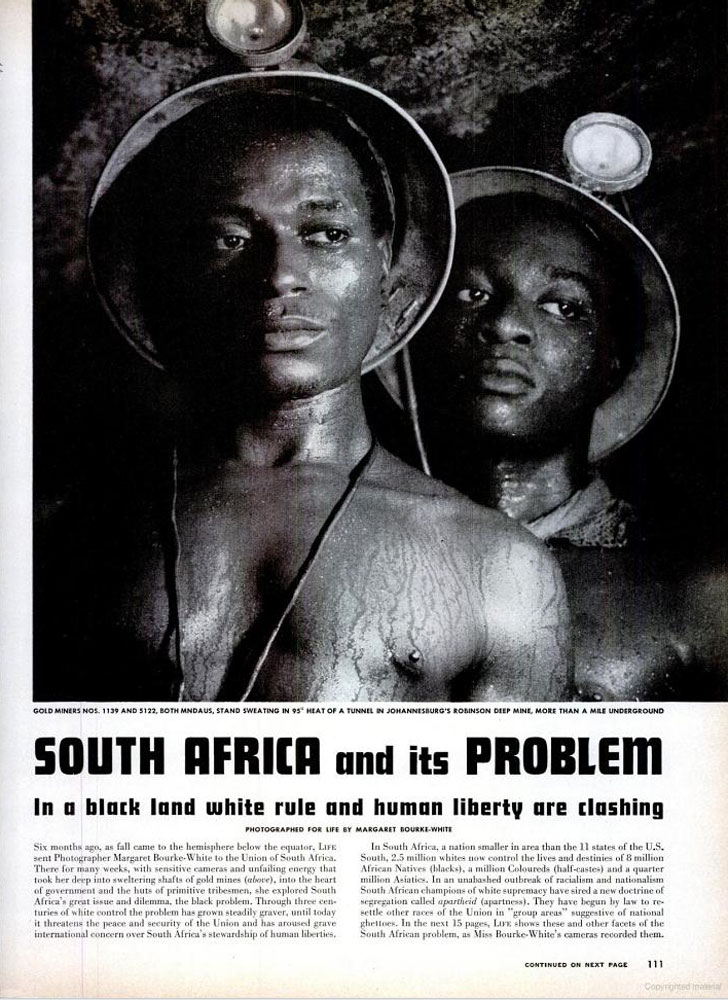

A photograph of two muscular young black men dominated the page. Their faces and shirtless torsos, drenched with sweat, filled the frame, giving them an almost palpable physical presence. Hard hats, tilted back to expose their faces, encircled their heads like halos. Lanterns on the hats and the dark rock behind the men told LIFE’s readers that they were miners.

The two men averted their eyes from the camera, their expressions composed but inscrutable. Who were these men behind their enigmatic masks? LIFE’s caption provided no answers. It identified them only as “Gold Miners Nos. 1139 and 5122,” the numbers the mine had assigned these “units.” On the opening page of “South Africa and Its Problem,” the photo essay that introduced America to apartheid, the men were symbols rather than individuals, emblems of oppression and exploitation.

“Apartheid,” a word that means, simply, “apart-hood,” will forever be associated with South Africa’s notorious system of racial domination and with the freedom struggle that brought it to an end. In 1950, when LIFE published its exposé, the word was still unfamiliar to most Americans. The term itself had begun to gain currency only after the South African National Party’s electoral victory in 1948.

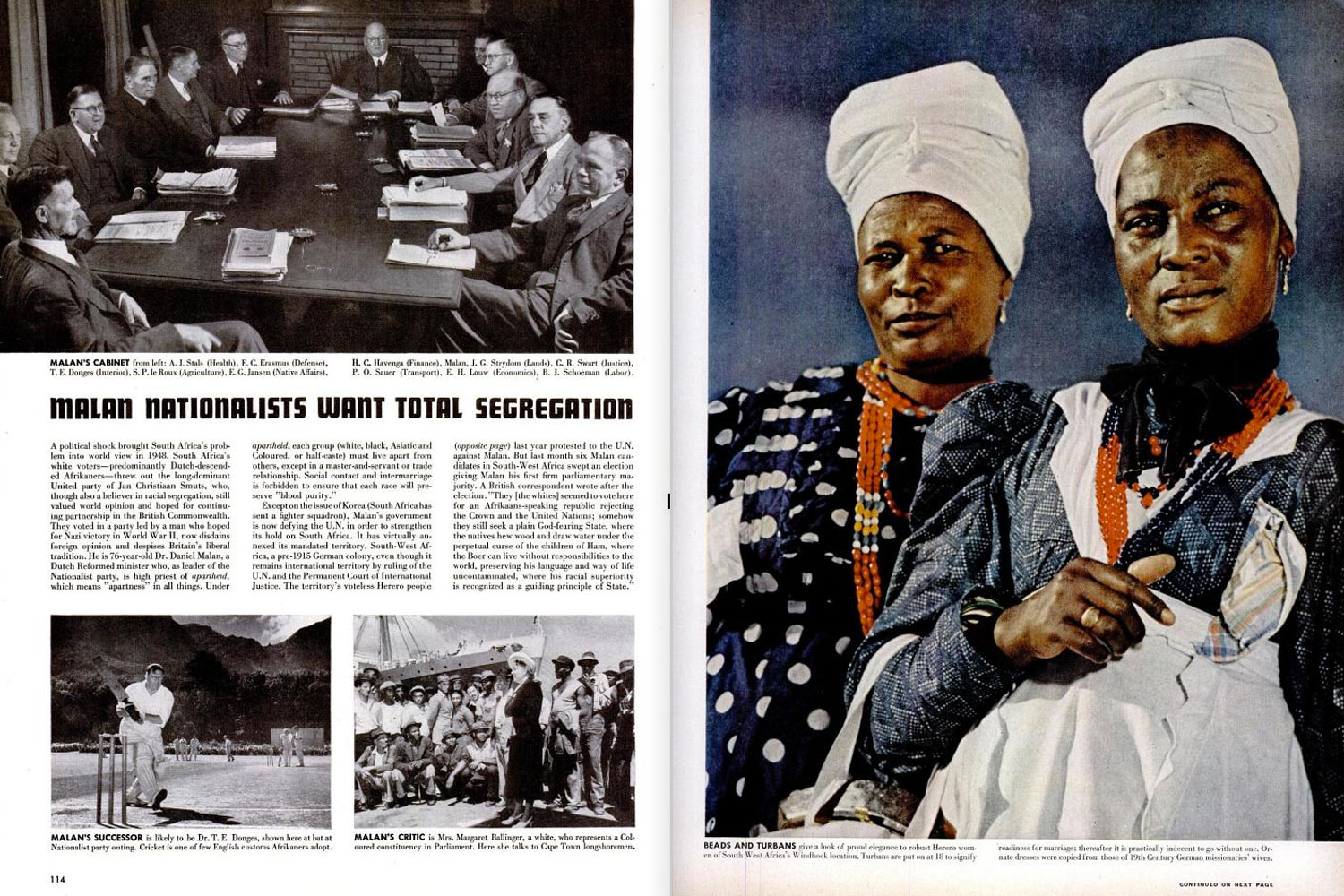

Although 300 years of colonialism had created a racial hierarchy, the party promised that apartheid would be more comprehensive than anything that had come before, ensuring that white supremacy would survive for generations to come. LIFE’s editors viewed apartheid as a troubling development. South Africa was an American ally, and this new, more virulent form of racism had the potential to destabilize the Cold War order. They assigned Margaret Bourke-White to produce the pictures that would explain apartheid to Americans.

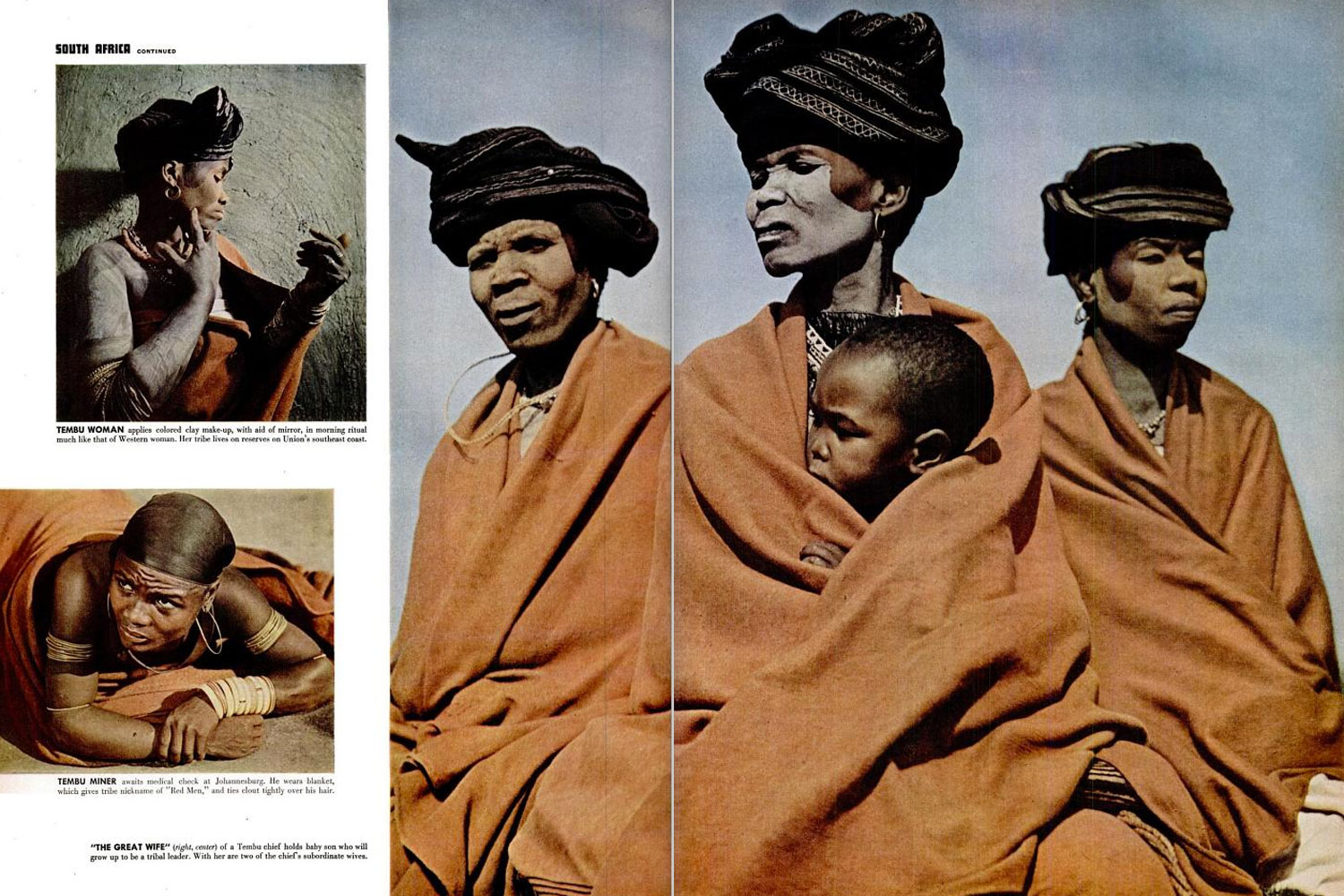

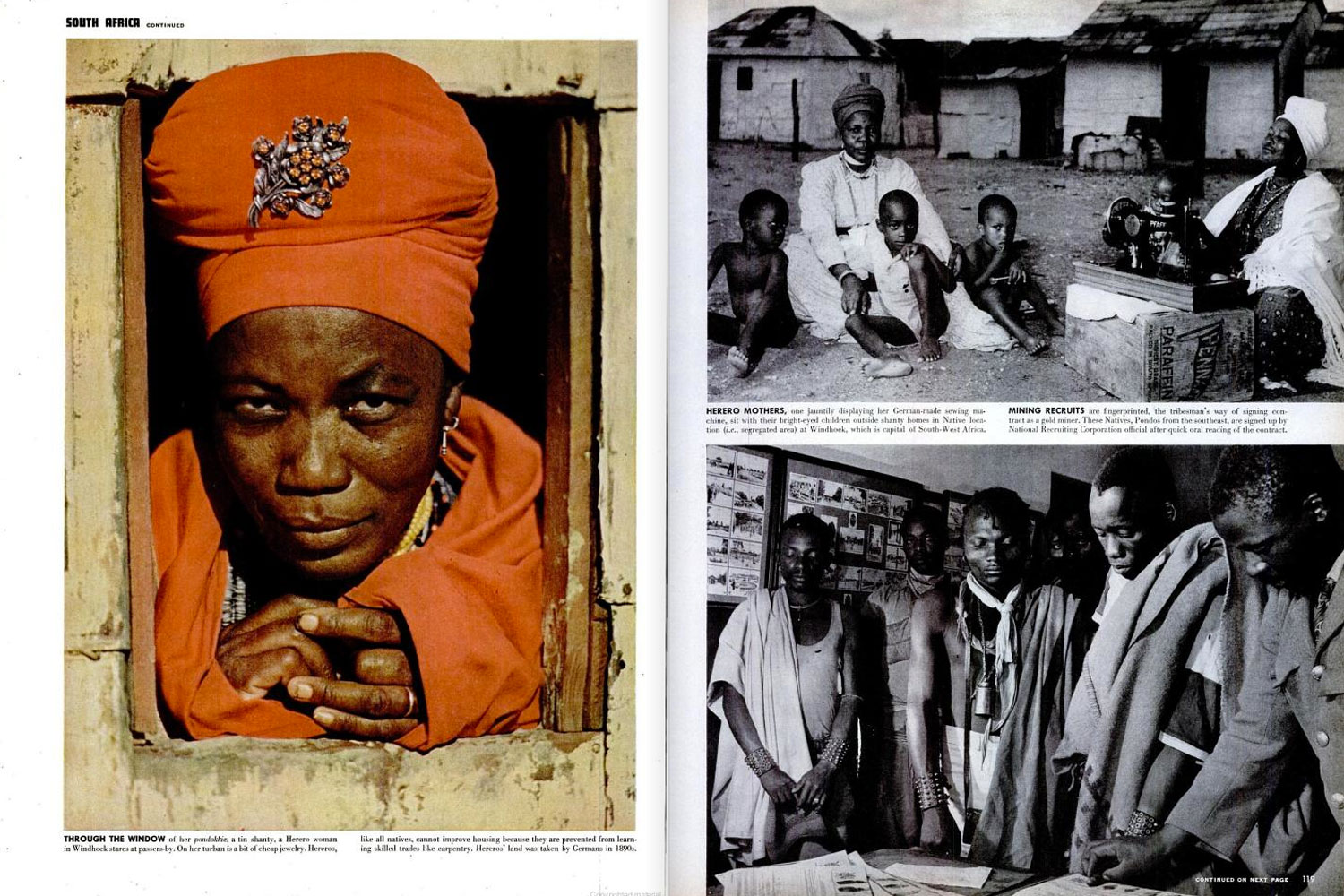

Bourke-White was an obvious choice for such an important assignment. Her compelling reportage for LIFE from the Soviet Union during World War II, from India at the time of independence and from throughout the United States during the Great Depression had made her one of the most famous and respected photojournalists of her era. She arrived in South Africa in late 1949 and left in mid-April 1950, traveling widely in South Africa proper and visiting South West Africa (now Namibia, then South Africa-governed) and Bechuanaland (now Botswana, then a British colony). She produced over 5,000 photographs, covering subjects that ranged from landscapes to cabinet ministers to “native” women in colorful costumes.

Margaret Bourke-White—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty

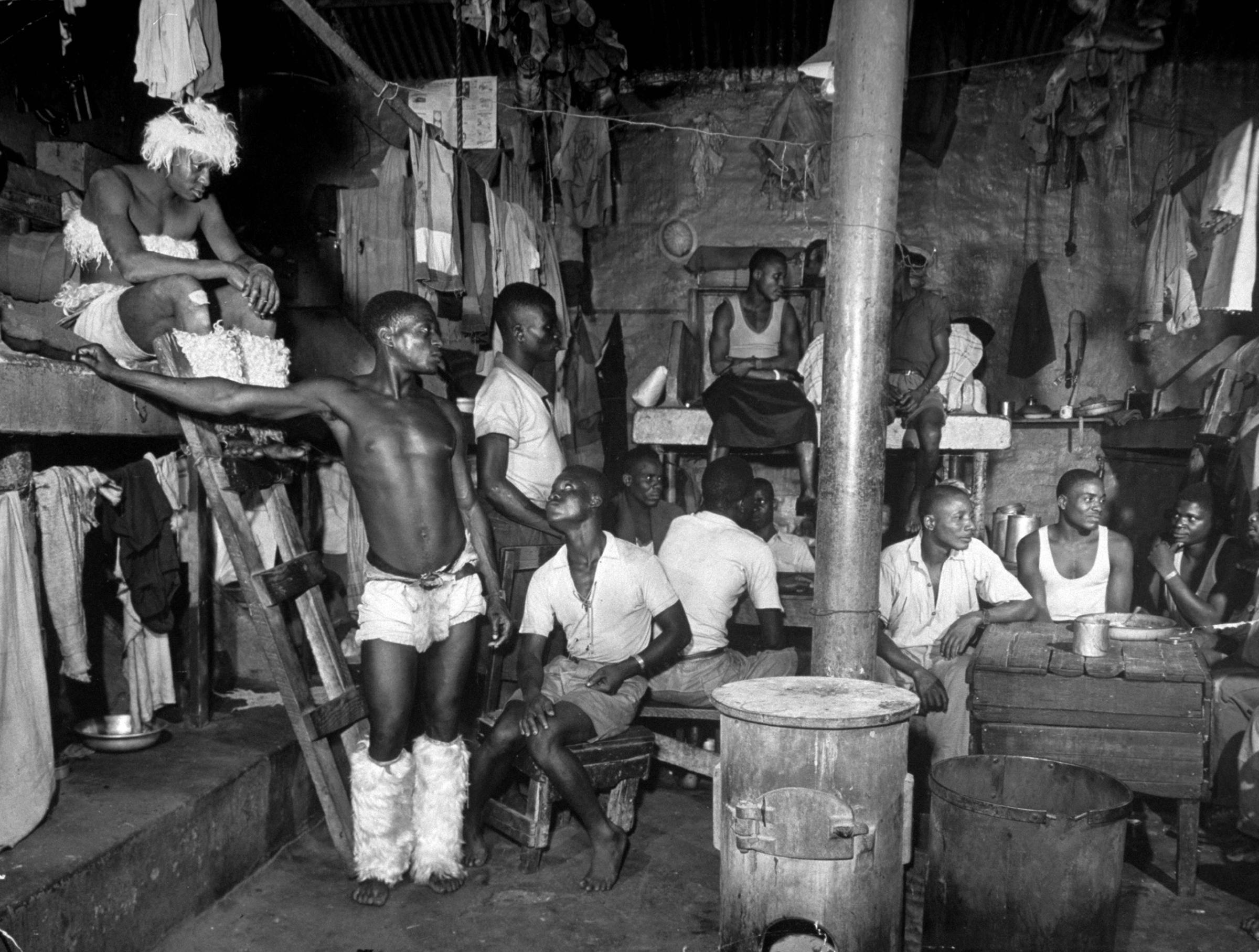

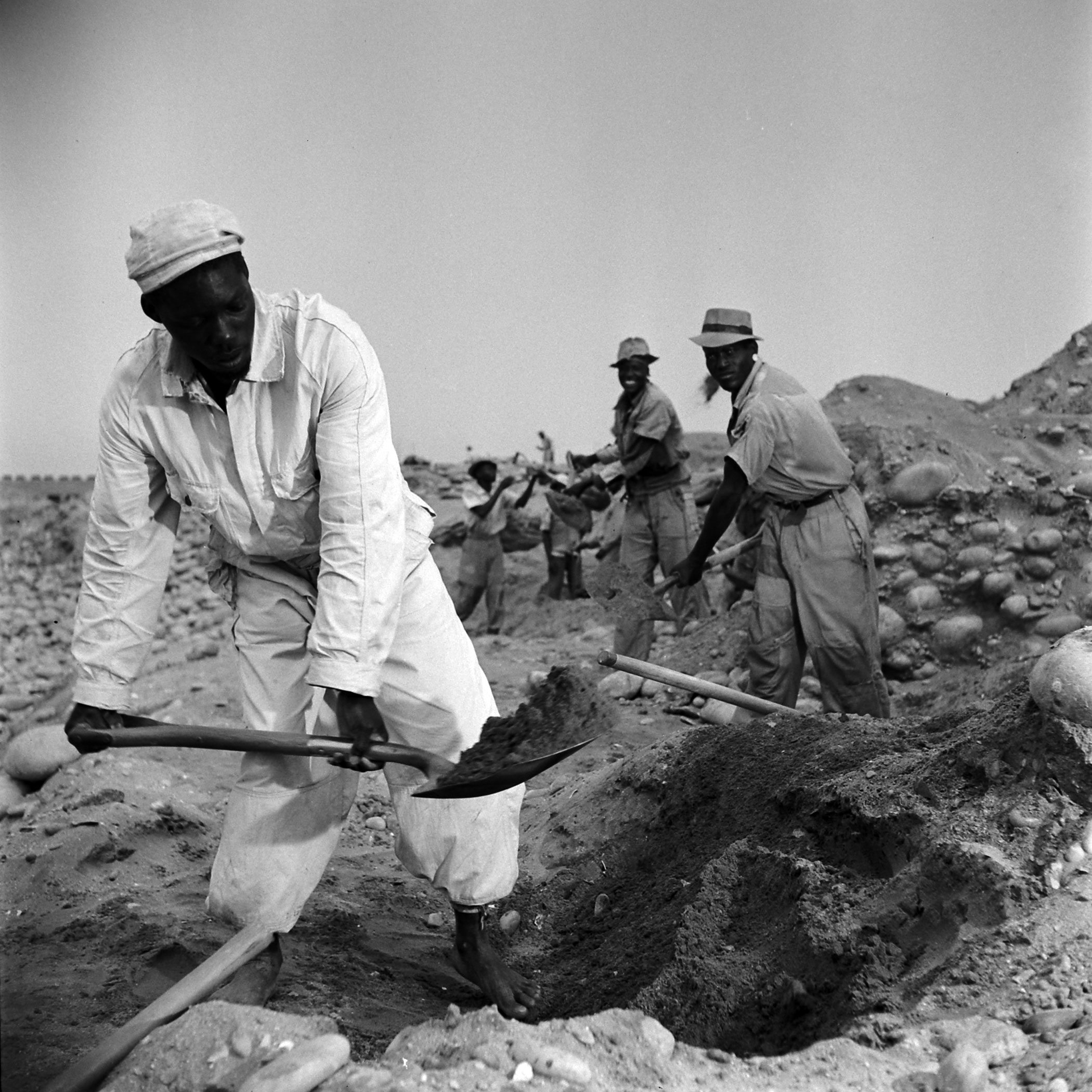

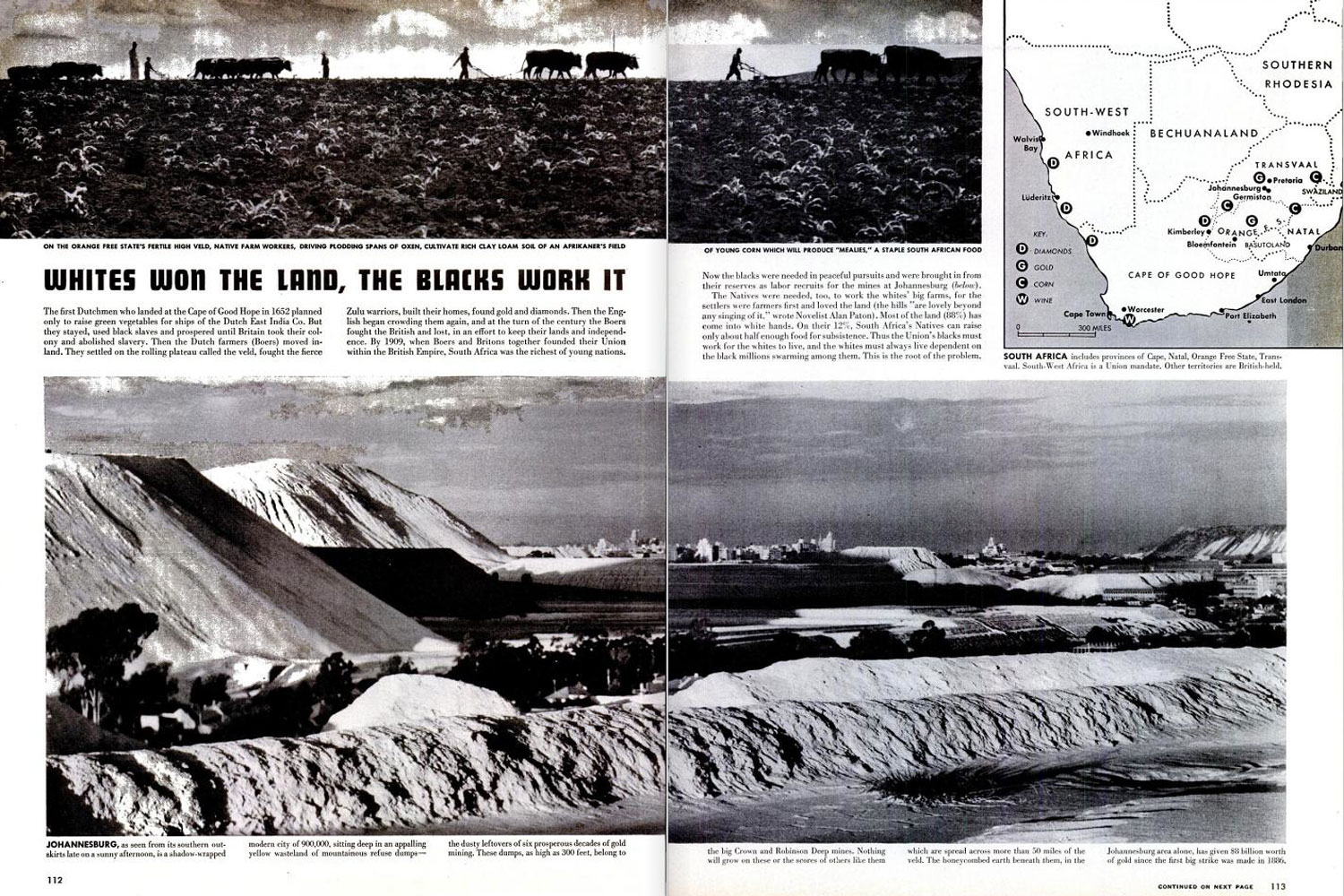

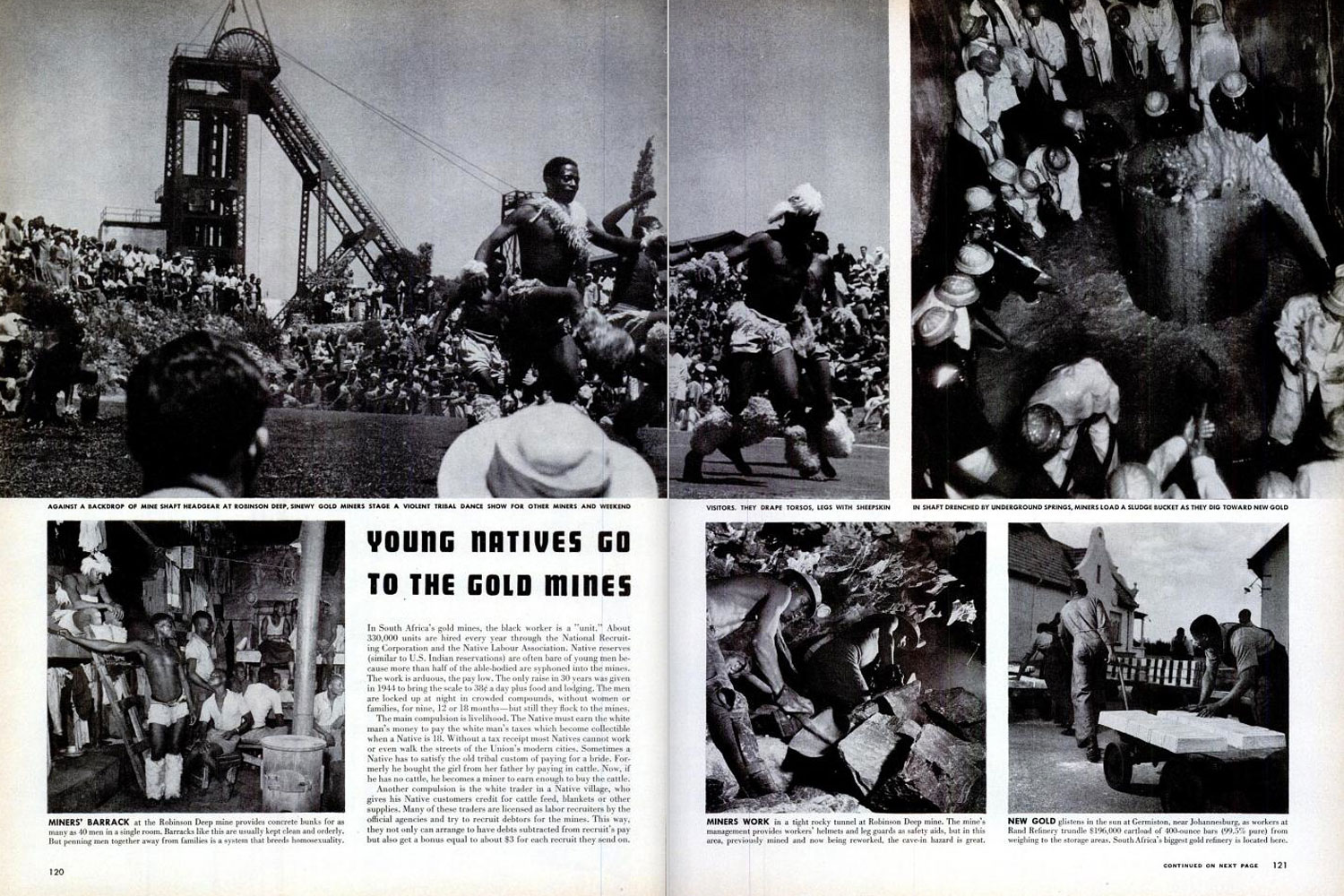

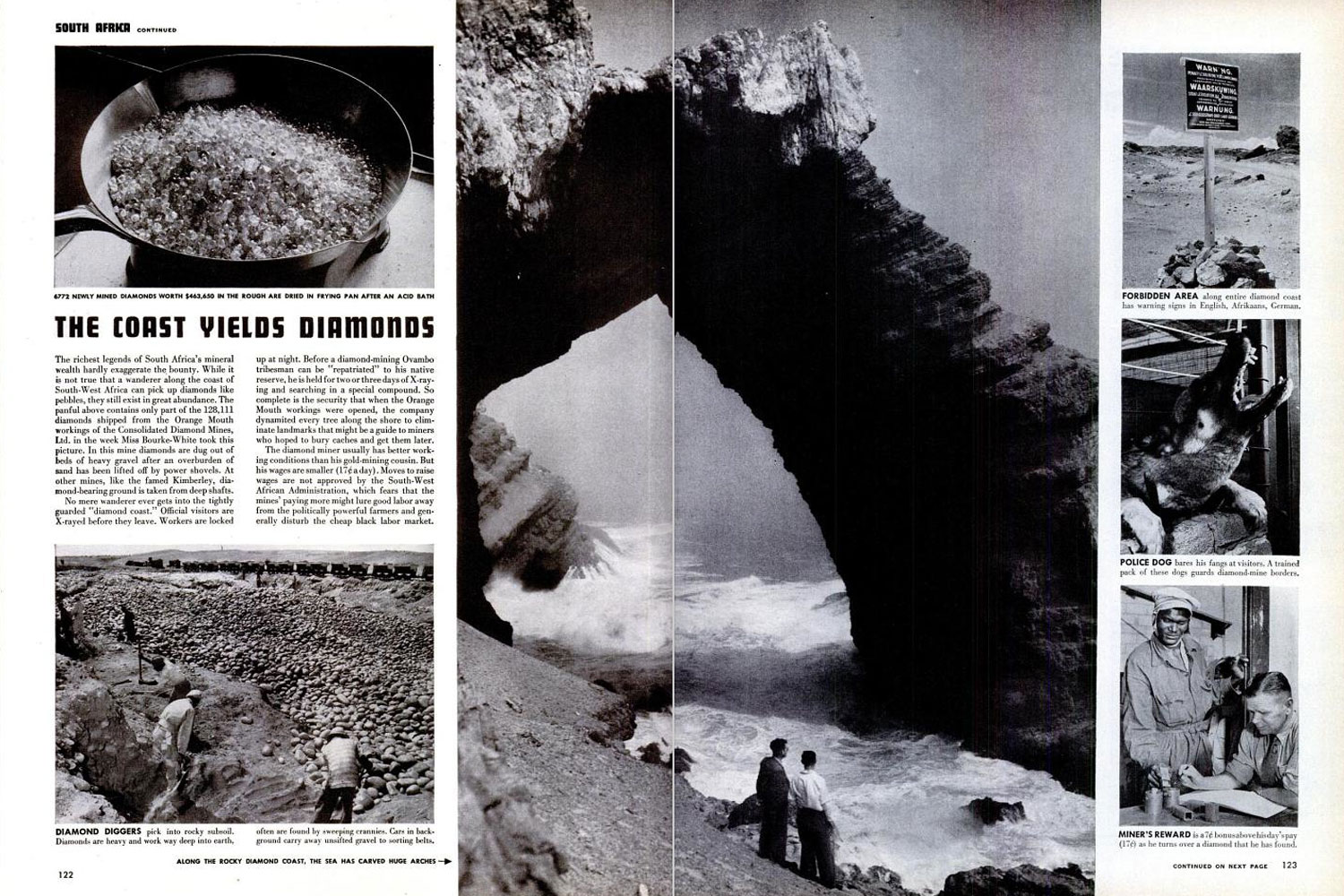

As her time in South Africa lengthened, Bourke-White increasingly turned her attention to the farms and gold and diamond mines that underpinned South Africa’s economy. She made some of the first photographs that captured the grueling conditions deep inside South Africa’s gold mines. She photographed convict laborers — most of whom had been found guilty of minor offenses — being marched at gunpoint to white farmers’ fields.

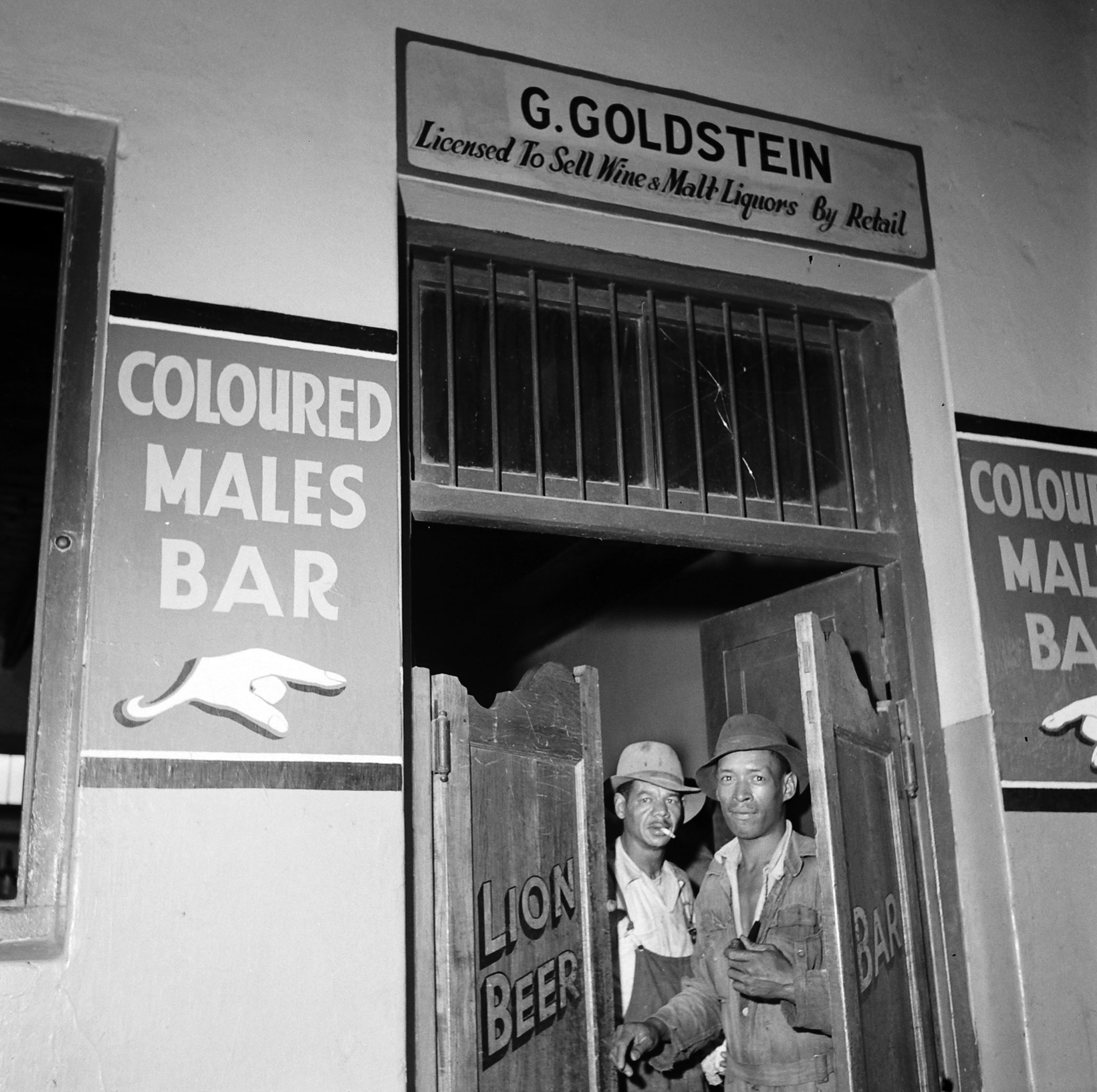

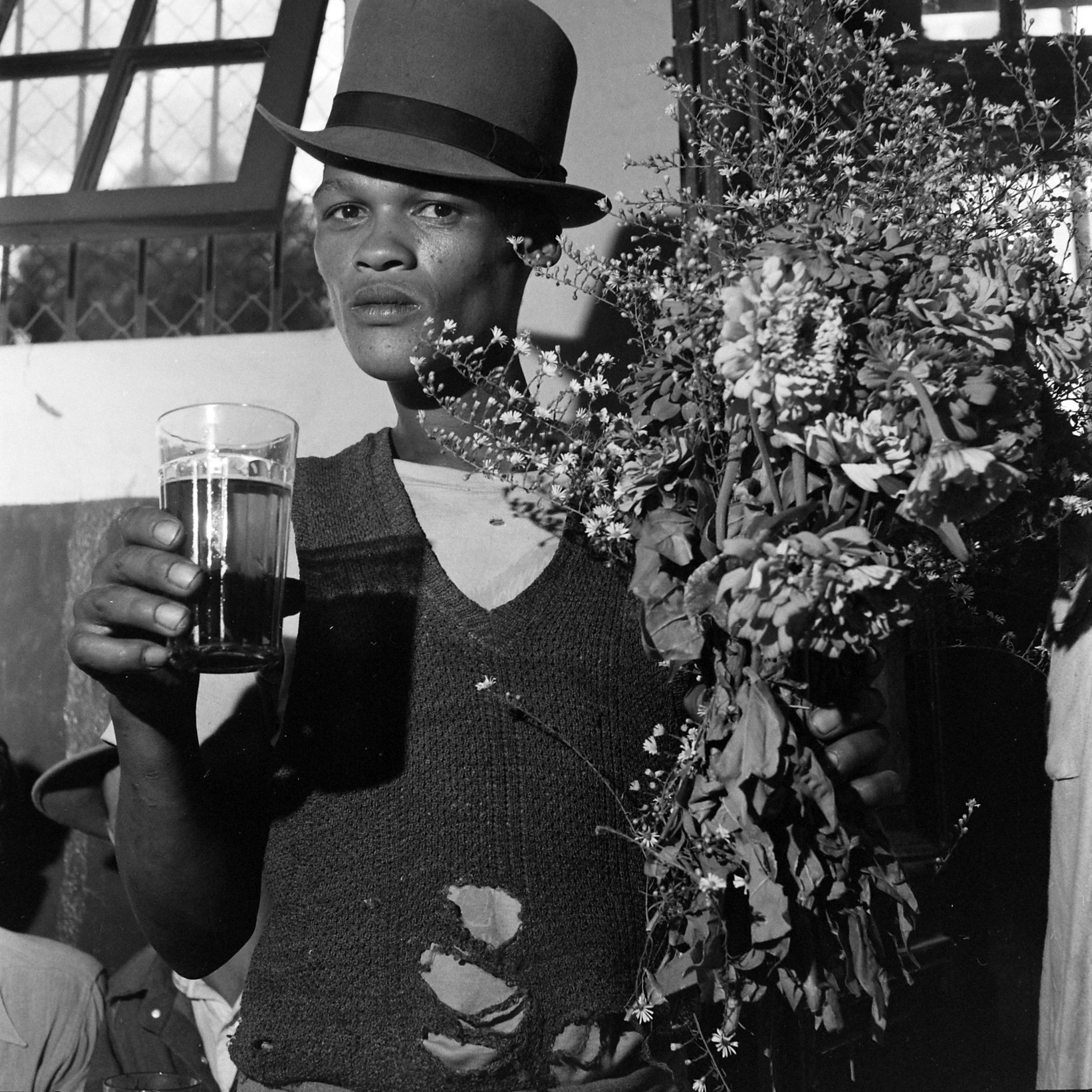

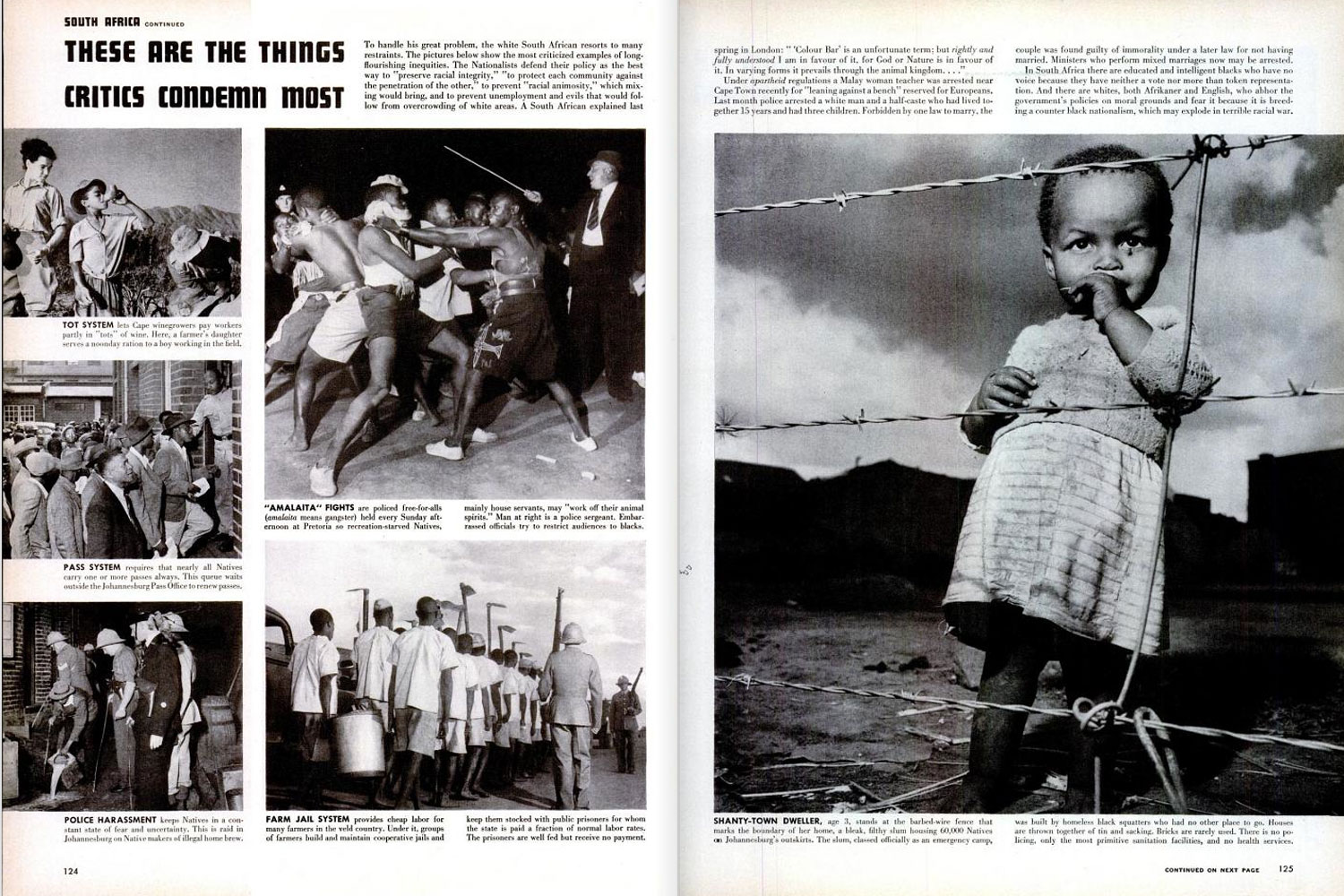

Her images exposed the wine farms’ infamous “tot system,” a practice that paid workers, some of them children, partly in cheap wine, thereby addicting them to alcohol and creating a dependent labor force. She showed African men queuing for passbooks, the degrading internal passports that allowed them to move around in the country of their birth. She photographed women and children amid the dirt and decay of urban shantytowns.

The photographs LIFE published in “South Africa and Its Problem” spoke eloquently about the indignities that blacks endured, the wealth that they created but did not enjoy, and about the political and economic structures that kept them in their place. It cast blacks as workers and “natives,” who were essentially passive in the face of an oppressive system. “The Whites Won the Land, the Blacks Work It,” one of LIFE’s headlines proclaimed. There seemed to be little hope for change

It was a convincing argument, but it was profoundly incomplete.

Modern readers are likely to wonder, after flipping through the essay, Where is Nelson Mandela? And where is the African National Congress (ANC) he led to power in 1994? More broadly they might ask, Where is any evidence at all of black activism? The evidence, in the form of Bourke-White’s photographs, existed. LIFE’s editors chose not to publish almost all of it and to minimize the rest.

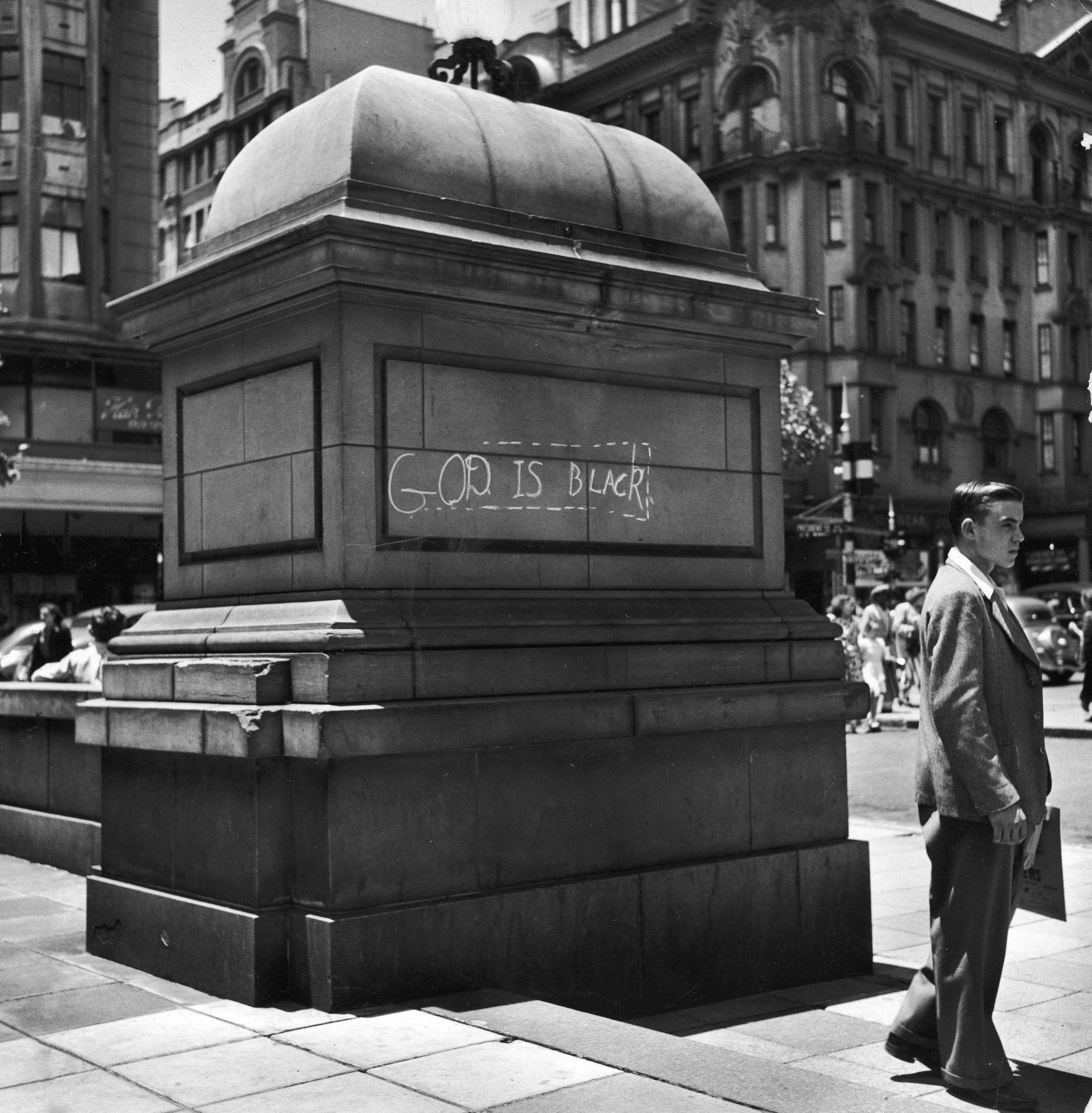

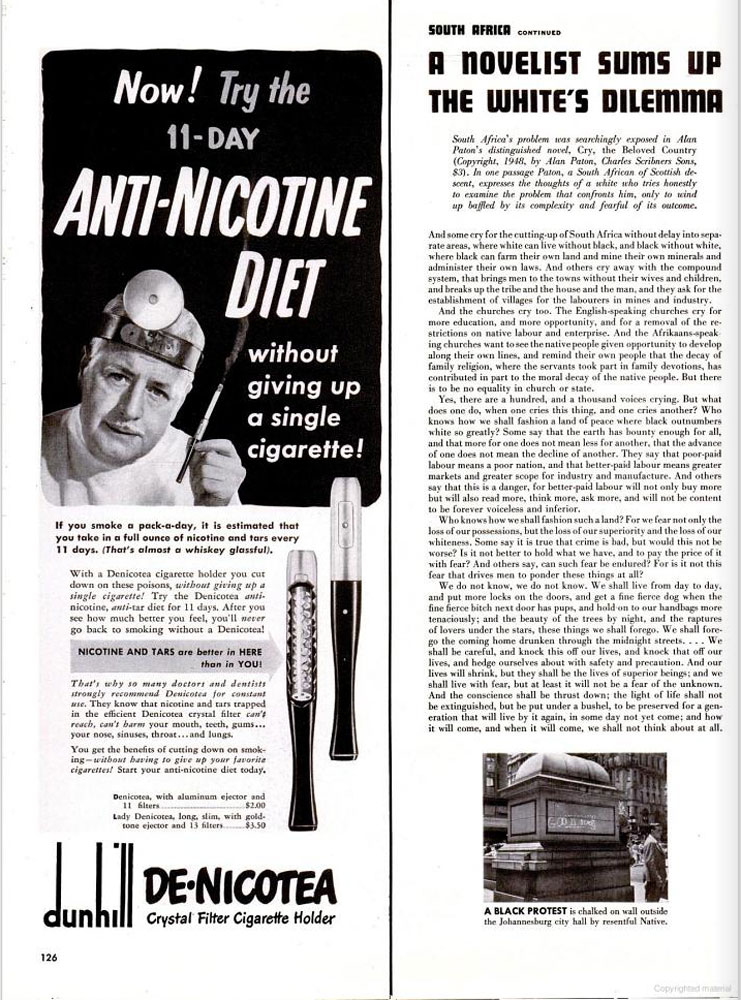

“South Africa and Its Problem” contains only the slightest hint of the activism that would ultimately transform the country, despite the fact that the 1940s and early 1950s were a time of tremendous cultural and political dynamism among black South Africans. The last photograph in the essay, and by far the smallest, was an image of an ornamental plinth in front of Johannesburg’s city hall. On it, somebody had scrawled, “God is Black.” LIFE explained the scene by saying that the words were written by “a resentful Native.” Bourke-White understood its deeper significance. In a note to her editors, written while she was still in South Africa, she explained that the message was “[s]ymptomatic of the growing racial self-consciousness of the black folk of South Africa.”

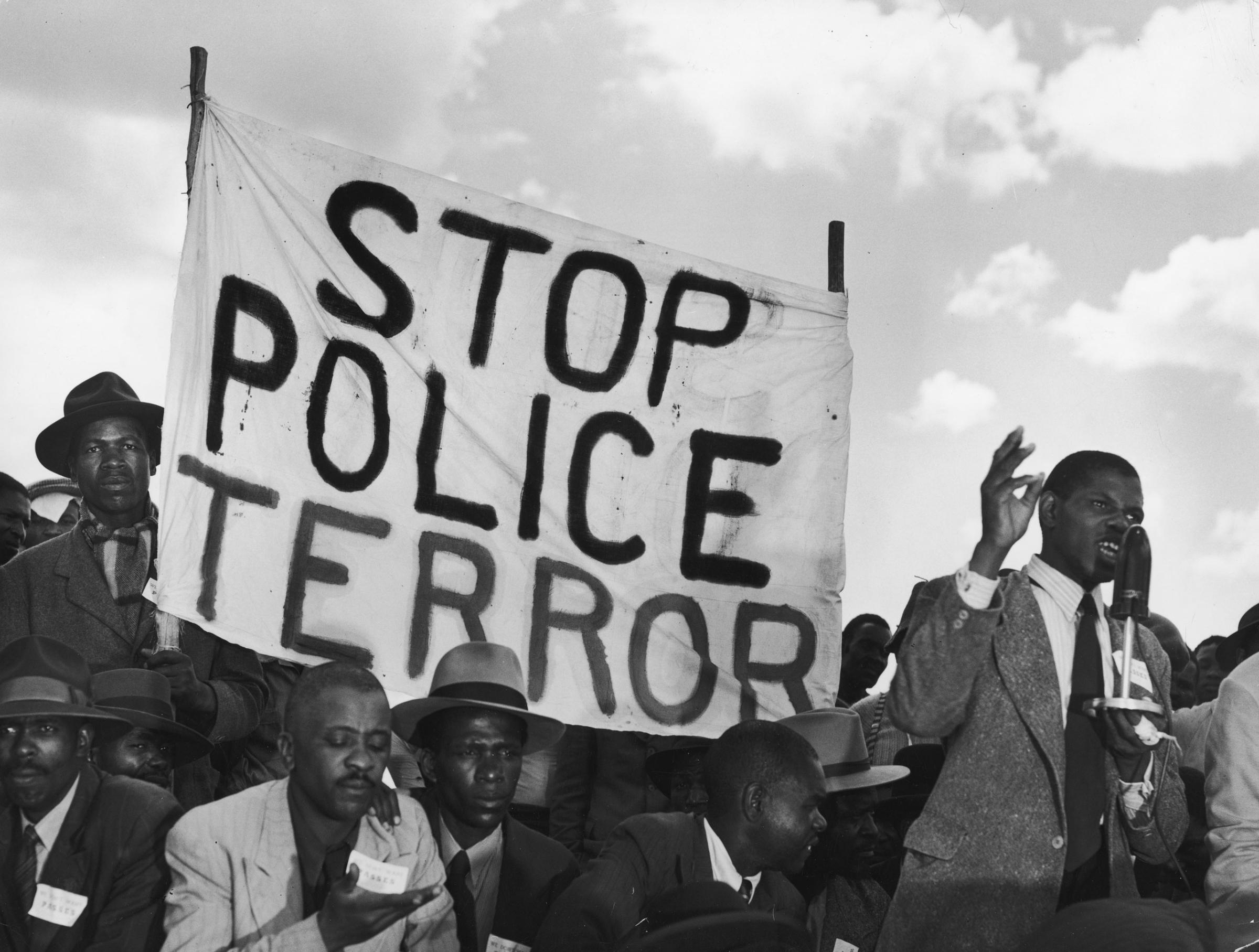

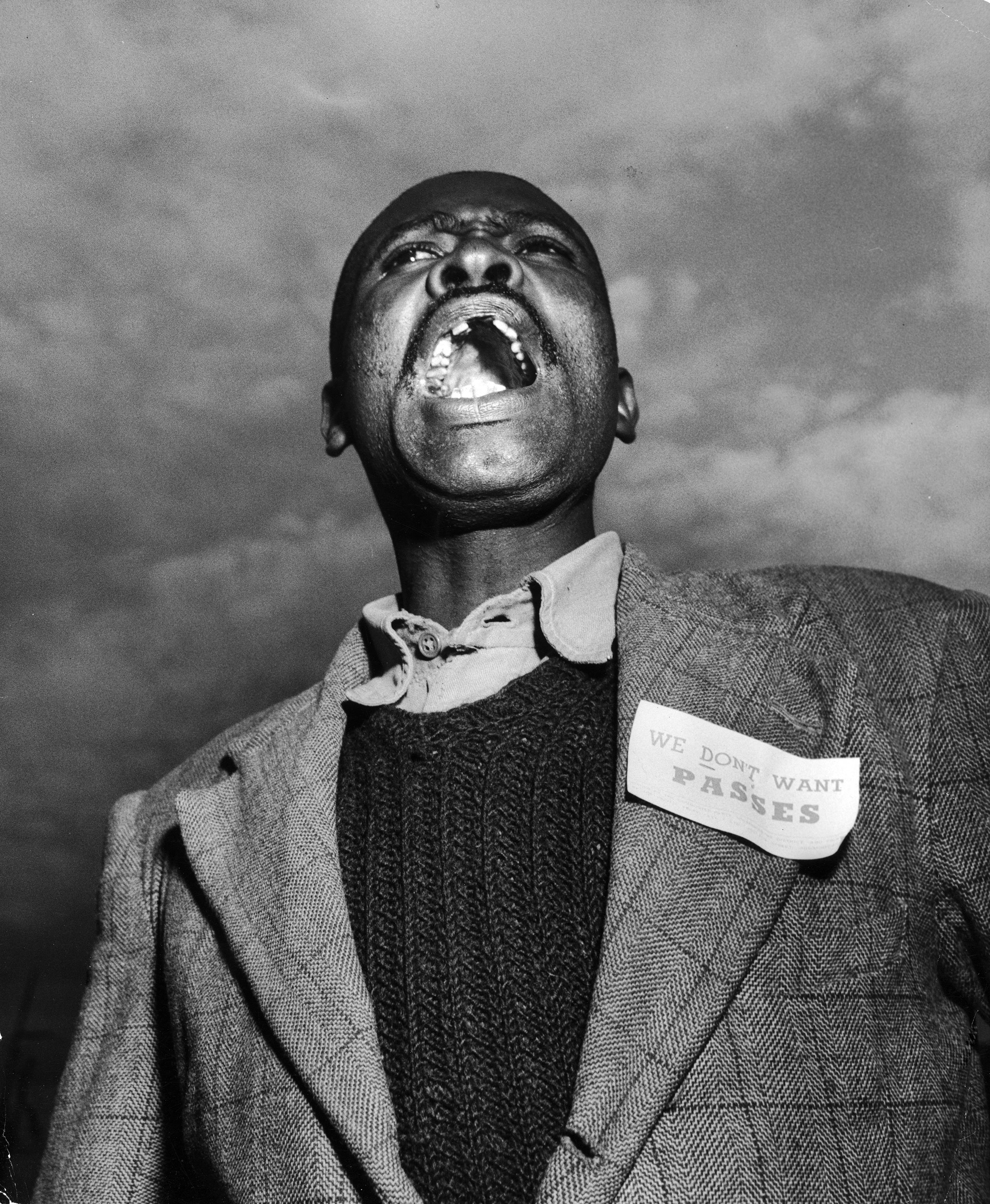

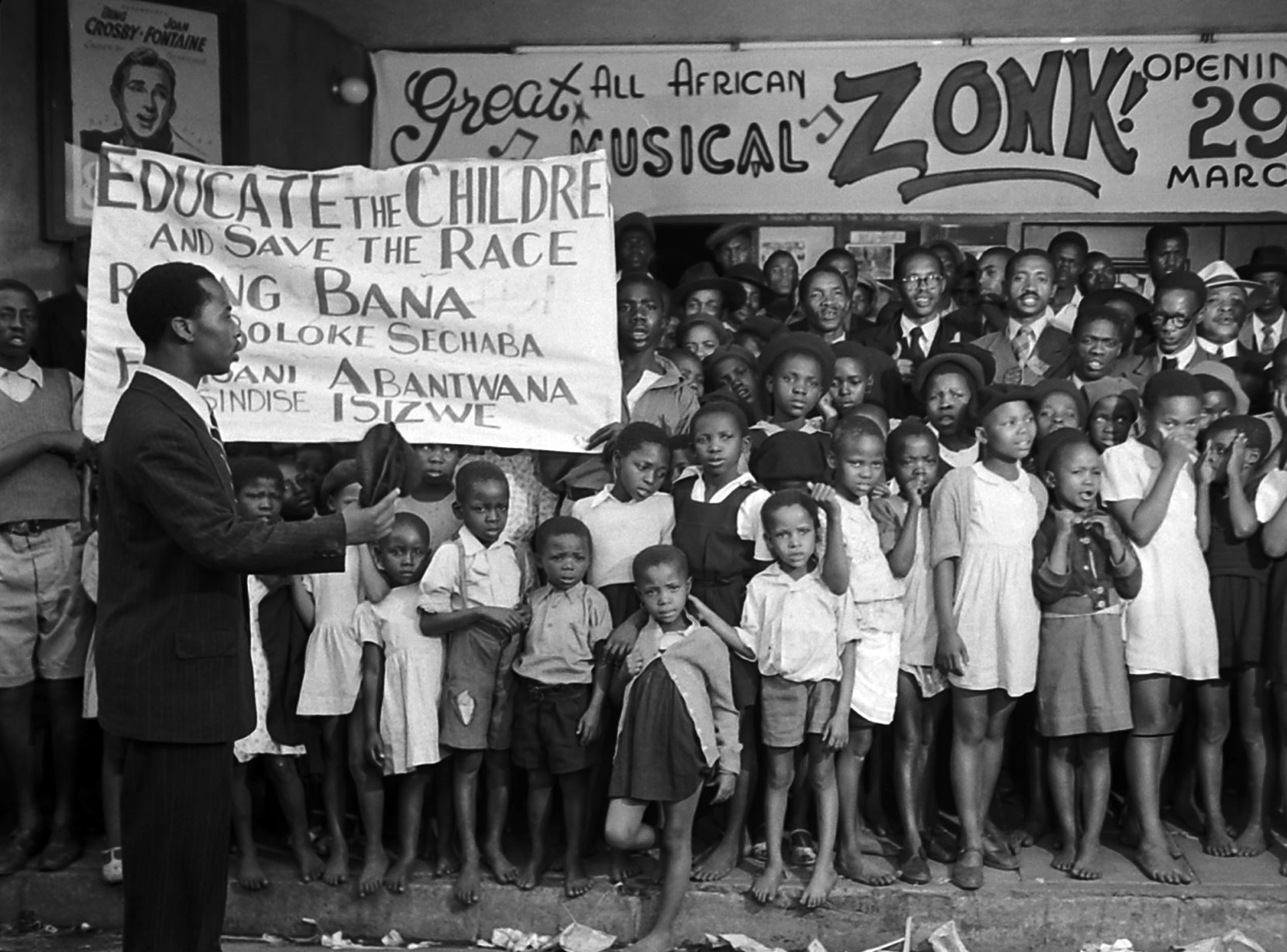

Bourke-White was aware of the changing self-consciousness because she had photographed and spoken with black activists and intellectuals. She photographed a rally that had been called to protest “Police Terror” and the hated passbooks. A close-up of Phillip Mbhele, one of the protestors, showed him wearing a badge that read, “We Don’t Want Passes.” She also photographed union meetings and a campaign that urged better education for African children. She made portraits of several anti-apartheid leaders, although not Nelson Mandela.

It is likely that LIFE’s editors chose not to publish these photographs because many of the demonstrations and activists that organized them were associated with the Communist Party of South Africa. (At this time, the ANC and most of its members, including Mandela, were hostile to communism. Neither ANC members nor activities appear in Bourke-White’s photographs.) Given the anti-communist fervor that pervaded American culture at the time, editors may well have believed that they were doing black South Africans a favor by remaining silent about activism. Ties to communism would have made it difficult for many readers sympathize with the freedom struggle.

The editors’ decision to hide what they knew about black activism did Bourke-White, their readers, and black South Africans — the vast majority of whom had nothing to do with communism — a disservice. It compromised an analysis of South African society that was otherwise as moving as it was convincing. “South Africa and Its Problem” created a flattened, one-dimensional representation of black communities by failing to reveal the cultural and political dynamism that would eventually free them.

Six decades after its publication, the photo essay remains a compelling analysis and explicit condemnation of racial injustice at the dawn of the apartheid era. If not for its omissions, though, it could have been so much more.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com