The first episode of the fifth season of Downton Abbey — which premiered for U.S. audiences on Sunday night — was, predictably, focused largely on the comings and goings of the suitors and staffers who populate the estate. But those characters, upstairs and down, were also concerned with someone who didn’t show up at all: Britain’s new Prime Minister, recently risen to power when the season kicks off in 1924.

But who is this new P.M., and why is he such a big deal?

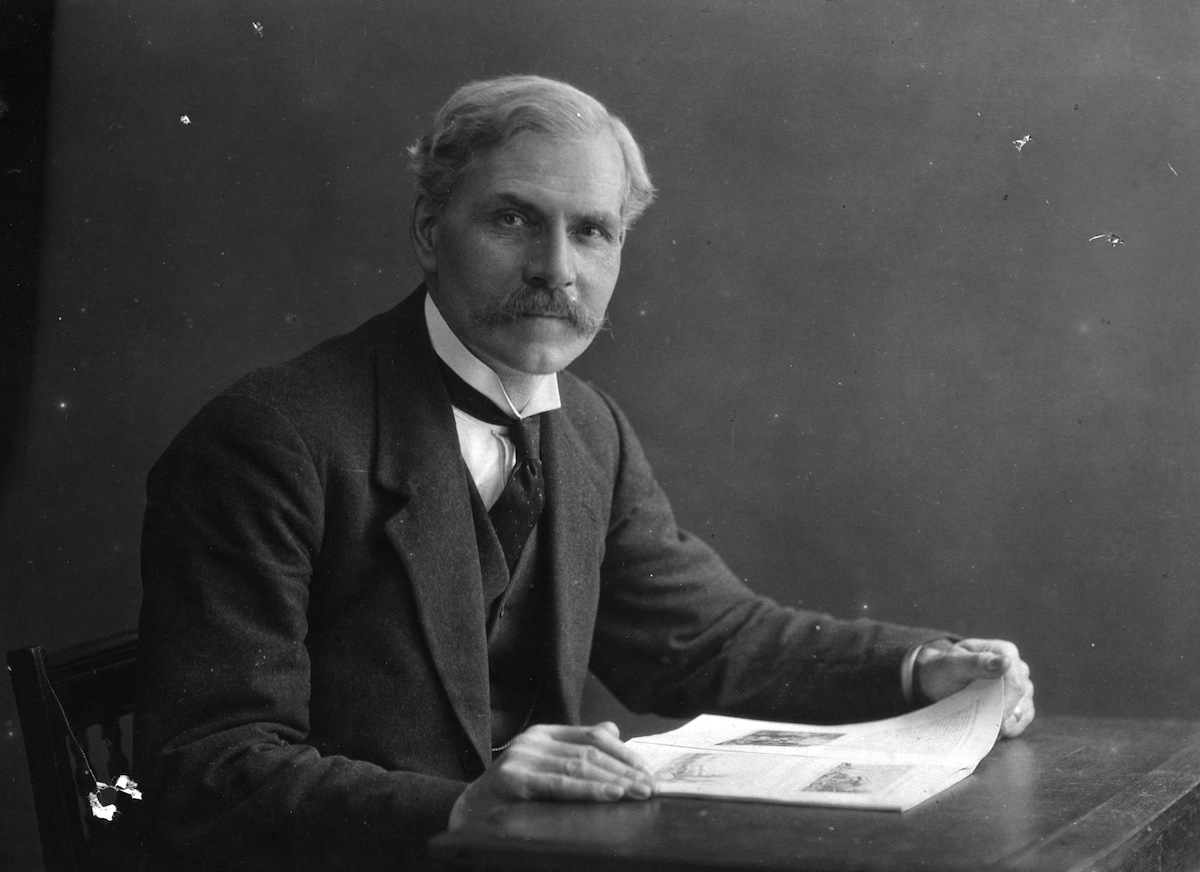

The man in question is James Ramsay MacDonald, and he was Britain’s first-ever Labor (or ‘Labour,’ per the British spelling) Prime Minister. Early in 1924, the then-Conservative leaders in the House of Commons informed the king that, with the help of Liberal Party support, a Labor Party push for a no-confidence motion had succeeded. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin resigned, along with his cabinet, and recommended MacDonald as his successor. The king agreed.

All of this was, at TIME noted back then, “the usual procedure of an outgoing Cabinet.” What was worth noting — and the reason why the folks at Downton would have been talking about the news more than usual — was MacDonald’s unusual personal background.

He was, as Lady Mary put it on the show, the son of a crofter (a farmhand), and as TIME put it in real life, “once a country yokel.” He studied and worked his way from a village to London and from manual labor to a political career. His pacifism got him shut out of the mainstream during World War I, but in 1922 he was reelected to the House. “The Times of London, says he is one of the most noteworthy of British Prime Ministers—an idealist and a pacifist guiding the country when idealism and pacifism are not the ruling passion of the world,” TIME reported in the Feb. 4, 1924, issue. “Henry William Massingham, famed Liberal editor of London, summed up Macdonald thus: ‘Not eloquent, but a statesman. A man of principle, but not a fanatic. Elastic without being supple. A character as stainless as Burke or Gladstone.'”

Though the makeup of Parliament meant that the left-leaning and once-radical MacDonald couldn’t do anything too extreme — the Labor party still needed the support of the Liberal party to maintain a majority over the Conservative party — he still represented a major shift in British political life. Just as Downton Abbey‘s Mr. Carson remarks again and again, the old ways were changing. Rigid lines between the classes had begun to blur, and it was possible for the first time for a man of modest background to exert power over politicians from wealthy and middle-class backgrounds.

The following year, TIME published a round-up of the Prime Ministers who had resided at No. 10 Downing Street since it was established as the official home of the office in 1735, and the difference was made clear. “Twenty-five were peers or the sons of peers, 8 were country gentlemen or members of well-connected families, 5 came from the so-called middleclass: Addington, son of a doctor; Disraeli, grandson of a merchant; Gladstone, son of a shipowner; Asquith, son of a manufacturer; George, son of an itinerant teacher,” the summary read. “The remaining one, Mr. Ramsay MacDonald, was born in the humblest circumstances, his relatives being fishers and farm hands.”

And, though nobody on Downton Abbey mentioned it, that political shift in 1924 brought change in more ways than one. McDonald’s new government included a new Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Labor. Her name was Margaret Bondfield, and she was the first woman in British history to become a cabinet minister.

Read TIME’s original coverage of MacDonald’s rise to power, here in the TIME Vault: Advent of Laborism

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com