Unemployment persists among military veterans as a sharply growing number of them are receiving disability payments from the Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a new study by a Stanford economist. The steep increase in such payments, Mark Duggan suggests, could be acting as a brake on their employment prospects.

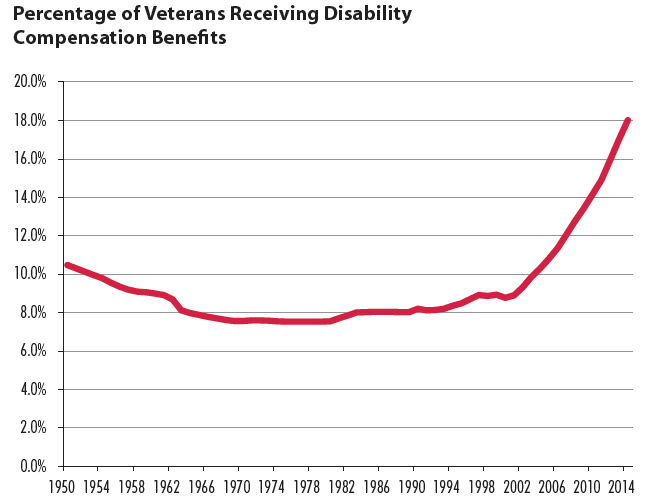

Veterans receiving disability compensation from the VA rose from 8.9% in 2001 to 18% this year, Duggan’s study says. Even as the number of veterans shrank from 26.1 million in 2001 to 22 million this year, those receiving federal money for wounds linked to military service have climbed from 2.3 million to 3.9 million.

“The substantial rise in Disability Compensation enrollment in recent years suggests that this program may be affecting labor market outcomes for military veterans,” Duggan writes. He cites two possible reasons:

— It can reduce a veteran’s “propensity to work because—with the additional income—he may now prefer additional leisure to work.”

— Additional work may also “prevent a veteran from qualifying for a higher level of Disability Compensation benefits—and thus increase the effective tax rate on work.”

The jobless rate among post-9/11 vets was 7.2% in October, compared to the nation’s 5.8% rate—and a 4.5% rate among all veterans.

The study “is important because it shows how the good intentions of the disability system can sabotage the well-being of veterans,” says Sally Satel, a one-time VA psychiatrist who now works at the conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank. But the report, she adds, could boomerang: “Talking about reforming the veterans’ disability system is a third-rail topic because, on superficial glance, it appears as if reformers want to deny veterans help.”

But Satel, a reform advocate, denies that. “Reformers urge that assistance be given in the most constructive way possible,” she says. “This means that the VA should go all-out in terms of treatment and rehabilitation, to maximize entry into the workforce and minimize exit from it.”

Some vets believe the report misses the point. Repeated deployments and the lack of a formal, uniformed and organized enemy, ground down the Americans who fought the post-9/11 wars, says Alex Lemons, a Marine sergeant who pulled three tours in Iraq, “A number of my friends were blown into many pieces and they never quite reassembled them,” he says. “You might look at this person and think they look fine despite scars, but then you find out they can’t stand for more than an hour a day, they have shrapnel that works its way out of their dermis and have to pry it out, they are near deaf without hearing aids, or they can’t pick up things as a result of nerve damage in a hand. It means they will never be qualified for many jobs.”

Lemons says it’s good that troops are coming forward seeking help for post-traumatic stress disorder, which has gone from the 10th most-common condition among vets on disability in 2000, to third in 2013. “In my infantry battalion the number of Marines who are on PTSD disability is not more than 35%,” he says, “even though I believe everyone who deployed with us has it.”

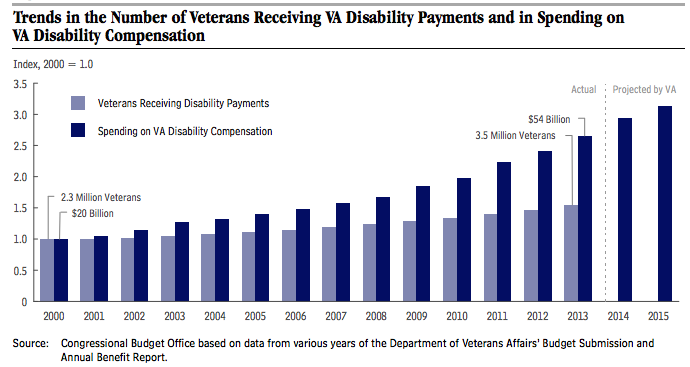

The average monthly disability payment grew 46%—from $747 to $1,094—between 2001 and 2013, Duggan reports. While that’s not much per veteran, the nation paid out a total of $54 billion in such benefits in 2013.

Not only are more veterans receiving disability compensation, Duggan’s report says, but they’re receiving more than earlier veterans did. That’s because the VA has ruled that the impact of their military service on their health is greater than for earlier generations of vets. Disability payments are pegged to a VA-determined rating, which is expressed in 10 percentage-point increments. Between 2001 and 2013, the number of vets deemed 10% disabled—generating an average monthly payment of $131 last year—dropped by 1%. Over the same period, the more than 800,000 vets rated 80% or more disabled—receiving an average monthly payment of $2,700—rose by 221%.

Military service also may have “become more demanding over time,” accounting for less veteran participating in the labor force, Duggan’s report says. “Consistent with this explanation,” he adds, “veterans have become more likely than non-veteran males to report that their health is poor or just fair rather than excellent, very good, or good.”

Elspeth Ritchie, a retired colonel who served as the Army’s top psychiatrist before retiring in 2010, believes the report slights what troops experienced in the nation’s post-9/11 wars. “It does not seem to factor in the high rate of physical injuries, traumatic brain injury and PTSD in the veterans from these conflicts,” she says.

Since turning its back on its veterans following the unpopular war in Vietnam, American society has sung the praises of its veterans, and has been footing the bills for those hurt to prove it. “Spending on veterans’ disability benefits has almost tripled since fiscal year 2000, from $20 billion in 2000 to $54 billion in 2013—an average annual increase of nearly 8%, after adjusting for inflation,” the Congressional Budget Office reported in August. “VA projects that such spending will total $60 billion in 2014 and $64 billion in 2015, a 19% increase from two years earlier.”

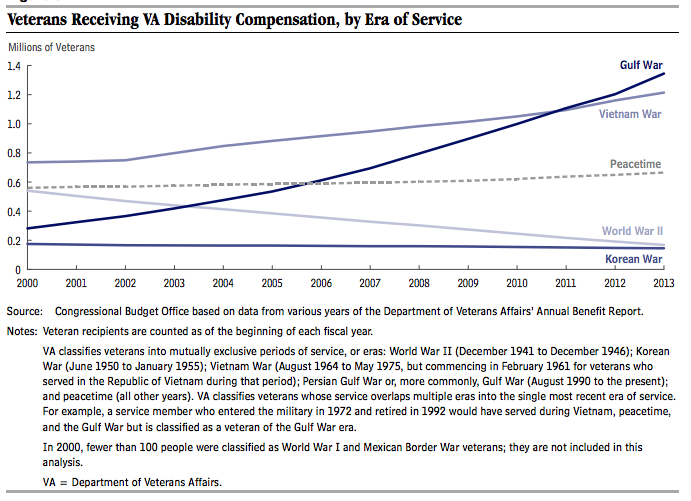

Duggan reports that a “key driver” in the growth of such benefits has been the VA’s decision to make veterans who served in southeast Asia during the Vietnam war eligible for benefits if they have Type 2 diabetes, ischemic heart disease, Parkinson’s disease, or B-cell leukemia. The agency took the action when it decided to “presume” the ailments were linked to military service in the theater and possible exposure there to the defoliant Agent Orange.

Today’s veterans, the study says, are more likely than their fathers to seek and gain VA disability benefits. Nearly one in four vets since 1990 are being compensated, compared to one in seven veterans prior to 1990. “This higher rate of enrollment may be primarily driven by the VA’s approval of presumptive conditions for Gulf War veterans who served in the Southwest Asia theater from 1990 to the present (including Iraq and Afghanistan),” Duggan found.

He also reports that while veterans between 1980 and 1999 were more like to be employed than non-veterans, that has flipped since 2000. “This significant reduction in labor force participation among veterans,” he adds, “closely coincides with their increase in Disability Compensation enrollment during this same period.”

Duggan notes that a 2010 change in VA regulations no longer required veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD to document their exposure to wartime trauma such as firefights or IED blasts. The number of veterans being compensated for PTSD rose from 133,789 in 2000 to 648,992 last year. “The percentage of all veterans on the Disability Compensation program with a diagnosis of PTSD has increased by a factor of six during this period,” Duggan writes, “from 0.5% in 2000 to 3.0% in 2013.”

The jump doesn’t surprise William Treseder, who deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq as a Marine sergeant. “Many post-9/11 vets can tell you stories about the inflation of VA claims,” he says. “We are often told to file for certain conditions—especially post-traumatic stress—whether or not we think it’s actually an issue. It’s the chicken-soup principle in action: can’t hurt; might help.”

Like Duggan, Treseder believes more study is needed examining the impact of disability payments on veterans. “This is much-needed research,” he says. “I’m glad to see someone out there looking into this.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com