You are getting a preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

The executioner’s rifle cracked across Cuba last week, and around the world voices hopefully cheering for a new democracy fell still. The men who had just won a popular revolution for old ideals—for democracy, justice and honest government—themselves picked up the arrogant tools of dictatorship. As its public urged them on, the Cuban rebel army shot more than 200 men, summarily convicted in drumhead courts, as torturers and mass murderers for the fallen Batista dictatorship. The constitution, a humanitarian document forbidding capital punishment, was overridden.

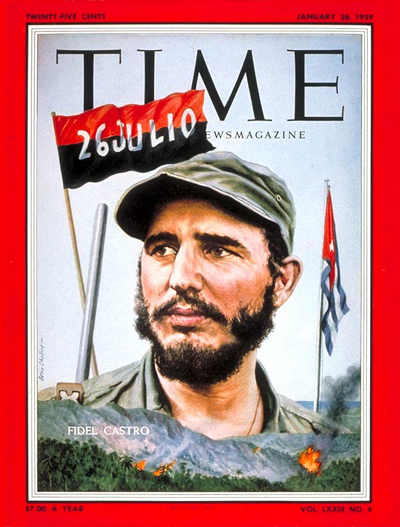

The only man who could have silenced the firing squads was Fidel Castro Ruz, the 32-year-old lawyer, fighter and visionary who led the rebellion. And Castro was in no mood for mercy. “They are criminals,” he said. “Everybody knows that. We give them a fair trial. Mothers come in and say, ‘This man killed my son.’ ” To demonstrate, Castro offered to stage the courts-martial in Havana’s Central Park—an unlikely spot for cool justice but perfect for a modern-day Madame Defarge.

In the trials rebels acted as prosecutor, defender and judge. Verdicts, quickly reached, were as quickly carried out. In Santiago the show was under the personal command of Fidel’s brother Raul, 28, a slit-eyed man who had already executed 30 “informers” during two years of guerrilla war. Raul’s firing squads worked in relays, and they worked hour after hour. Said Raul: “There’s always a priest on hand to hear the last confession.”

In a Mass Grave. The biggest bloodletting took place one morning at Santiago’s Campo de Tiro firing range, in sight of the San Juan Hill, where Teddy Roosevelt charged. A bulldozer ripped out a trench 40 ft. long, 10 ft. wide and 10 ft. deep. At nearby Boniato prison, six priests heard last confessions. Before dawn buses rolled out to the range and the condemned men dismounted, their hands tied, their faces drawn. Some pleaded that they had been rebel sympathizers all along; some wept; most stood silent. One broke for the woods, was caught and dragged back. Half got blindfolds.

A priest led two of the prisoners through the glare of truck headlights to the edge of the trench and then stepped back. Six rebel executioners fired, and the bodies jackknifed into the grave. Two more prisoners stepped forward, then two more and two more—and the grave slowly filled. Lieut. Enrique Despaigne, charged with 53 murders, got a three-hour reprieve at the request of TV cameramen, who wanted the light of a full dawn.

When his turn came, Despaigne was allowed to write a note to his son, smoke a final cigarette and—to show his scorn and nerve—to shout the order for his own execution. On a hill overlooking the range, a crowd gathered and cheered as each volley rang out. “Kill them, kill them,” the spectators bellowed. As the death toll reached 52 and the pit was halfway full, one rebel muttered: “Get it over quickly. I have a pain in my soul.”

By noon 70 prisoners had died. The Santiago rebels also sentenced ten men to ten-year jail terms and acquitted 47. In Camagŭey 19 prisoners were shot, in Matanzas twelve, in Santa Clara 30, in Cienfuegos eight. Almost all were followed by a coup de grace—two .45 slugs fired into the head of a man already dead. Havana jails held 800 accused men; the government estimated that, in all, 2,000 would stand trial.

Misgivings. The world looked on, tried to understand the provocation, boggled at the bloodshed. Uruguay’s U.N. delegate, Argentina’s Cuban ambassador, liberal U.S. Senator Wayne Morse, all protested. Puerto Rico’s Governor Luis Munoz Marin was “perturbed.” Castro’s answer: “We have given orders to shoot every last one of those murderers, and if we have to oppose world opinion to carry out justice, we are ready to do it.” He added a few irresponsible crowd pleasers: “If the Americans do not like what is happening, they can send in the Marines; then there will be 200,000 gringos dead. We will make trenches in the streets.” Although the U.S. had done nothing more than recognize his regime swiftly, he denounced “cannon diplomacy” and called for a rally of 500,000 this week in Havana.

No Cuban voices rose in protest, though there were doubtless many private misgivings. Sticking up for calm justice might be misinterpreted as sticking up for the tyrant Batista—a dangerous practice in Cuba today. Overwhelming public opinion, especially among women, urged the firing squads on.

As he walked with his entourage through the lobby of the Havana Hilton last week, Castro stopped to talk with two old women, who blubbered a request that their murdered sons be avenged. “It is because of people like you.” said Castro, hugging the pair, “that I am determined to show no mercy.” All over Cuba, the justly aggrieved, the crackpot patriots and anyone who just wanted to square a minor account filled their black notebooks with the names of new candidates for rebel justice. Fidel Castro estimated that fewer than 450 would be shot; Raul Castro bragged that “a thousand may die.”

A Special Moral Climate. The spectacle of Cuban killing Cuban and calling it justice was nothing new to history. Two of the country’s rulers deservedly got the nickname “Butcher” (see box). Men still alive today saw the carnage of Spanish rule, and their sons died in the streets in the 1933 massacre. Capable of high idealism and warm generosity, Cubans are also endowed to the full with the Latin capacity for brooding revenge and blood purges. Two wrongs, in many Cuban minds, do make a right. They quote a Spanish proverb: “Have patience and you will see your enemy’s funeral procession.”

This set of mind fed, under Batista, on a rich diet of police terrorism, often starkly visible. Many of the Batista cops who faced the firing squads last week were proved killers whose twisted minds drew pleasure from pain. To extract secrets from captured rebels, they yanked out fingernails, carbonized hands and feet in red-hot vises. Castration was a major police weapon.

Bodies were left in sun-speckled streets as police warnings. One Santiago cop of the Batista regime, trying to break down a rebel woman, brought one of her brother’s eyeballs on a platter to her cell. Other rebels were forced to watch their wives raped by cops. A U.S. resident of Santiago, who chanced upon Police Chief Rafael Salas Canizares shooting four young rebels dead in the street, reported: “He was in a state of maniacal ecstasy—face flushed, eyes bright, breathing hard.”

But reporters trying to run down atrocity stories often found them to be rumors or plants. And Batista had streaks of mercy: most of today’s rebel leaders, including the Castros, once jailed, were freed by Batista and lived to fight him again.

Habitual Corruption. Political morality under Batista, while conforming to a half-century of practice, hardly lived up to the idealistic constitution. During his seven years the gross national product soared from $2 billion to $2.6 billion, but the public debt rose from $200 million to $1.5 billion. Corruption ranged all the way from army sergeants who stole chickens to Batista himself, who shared with his cronies a 30% kickback on public-works contracts. Potbellied Chief of Staff Francisco Tabernilla and his family made off with the entire army retirement fund of $40 million. Havana storekeepers who wanted to attract crowds by having a bus-stop sign out front could get one any time—for a flat payment of $4,000 to traffic officials.

In Batista’s last years Havana became the Western Hemisphere’s capital of lust and license, with touches of depravity and opulence unmatched anywhere. Brothels, such as the Mambo Club, with chic girls, matronly overseers and a consulting physician, catered to U.S. tourists. Cheaper cribs along Virtues Street enticed Cubans. There were 10,000 harlots and as many panderers. Payoffs from prostitution and gambling ran into the millions and were efficiently organized, e.g., Batista’s brother-in-law had charge of slot machines.

Graft and terror inflamed Cuba’s people against Batista and helped add Cuba to Latin America’s four-year chain of democratic upheavals. But in Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela, the army, while shucking its dictator-boss, remained nearly intact and moderated the transition to free elections. In Cuba, as in the Mexico of 1910, the people rose to smash the army. The only force left in Cuba is fidelismo, an adherence to whatever scheme pops into the hero’s mind.

Living on Euphoria. Fidel Castro himself is egotistic, impulsive, immature, disorganized. A spellbinding romantic, he can talk spontaneously for as much as five hours without strain. He hates desks—behind which he may have to sit to run Cuba. He sleeps irregularly or forgets to sleep, living on euphoria. He has always been late for everything, whether leading a combat patrol or speaking last week to the Havana Rotary Club, where a blue-ribbon audience waited 4¾ hours for his arrival. Wildly, he blasted U.S. arms aid to Batista, but he paid a friendly call at 1 a.m. on the ambassador from Britain, which sold tanks and planes to Batista for nearly a year after the U.S. had stopped.

Castro has the Cuban moralistic streak in spades, showing no apparent affection for money or soft living. He considers himself a Roman Catholic but is also impressed by Patriot José Marti’s anticlerical tomes. He has to be cajoled into changing his filthy fatigue jacket. His only luxury is 50¢ Montecristo cigars.

He is full of soaring, vaguely leftist hopes for Cuba’s future but has no clear program. Other Latin American leaders trust his democratic professions, hope that his shortcomings will not bring on disorder and another dictatorship.

Symbol on a Hill. Castro has confidence, physical courage, shrewdness, generosity and luck—qualities that will one day plant his statue in some Havana plaza. He won his long war not by fighting but by perching in sublime self-confidence on the highest mountain range in Cuba for more than two years, proving that Batista could be flouted. He became the symbol of his rebellious country, pulled quarreling rebel factions together and inspired them to face down a modern army.

“I was born in Oriente province. That’s like Texas for Americans,” says Fidel Castro, in explanation of his feats. “It is the biggest province in Cuba. We do the most work, we make the most rum and sugar, we make the most money too. We hate dictators.”

The Planter’s Son. Castro’s father, Angel Castro, a penniless immigrant from the Spanish region of Galicia, had already worked hard and made plenty of money by the time Fidel was born in 1926. Fidel Castro grew up as the planter’s son on a $500,000 sugar plantation at Mayari, 50 miles from Santiago. He was in love with guns from the time he fired his first .22, hunting in the mountains where he would one day return, an outlaw. From the age of eight he spent most of his time at a Roman Catholic boarding school in Santiago ; his younger brother Raul, a quarrelsome, envious youngster of five, tagged along. “For the next eleven years,” a priest recalls, “we Jesuits had Fidel.”

Moving to Havana, Castro enrolled at the Jesuits’ Belen College, got interested in politics. Like many another Cuban student, he kept a revolver or two around the dormitory. He worked his way up through student politics at Belen and Havana University (1945-50), got hauled in twice for questioning about political murders.

In 1947, when the vanguard of 1,100 hot-eyed Caribbean revolutionaries set out in a ship from Cuba’s eastern coast, bound east to invade Dictator Rafael Leonidas Trujillo’s Dominican Republic, idealistic Fidel Castro was aboard. Cuban gunboats intercepted the rebels and Castro swam three miles to shore, his Tommy gun still on his back. He turned to law, defended a few friends in political trouble, a few farmers evicted from their plots; he honeymooned in New York with his bride Mirtha. fathered a son named Fidel, settled down in Havana. At 2:43 on the morning of March 10, 1952. Fulgencio Batista—who had been Cuba’s behind-the-scenes ruler for some ten years—seized Cuba by army coup. Castro, a candidate for Congress in the elections that Batista canceled, at once found his cause.

He sold his law books and car, recruited his brother Raul and 150-odd friends, raised $20,000 for guns and contraband army uniforms. At dawn on July 26. 1953, Fidel Castro led a column of 13 cars to the walls of Santiago’s bristling Moncada barracks, a yellow stone pile where 1,000 Batista troops lay sleeping. A suspicious Jeep patrol came up. Castro, then 26, stepped out, raised his twelve-gauge shotgun and shot his first man. “That was the mistake,” he recalls. “I had told them all to do what I did, and they all opened fire.” The attack was stopped cold; Batista’s cops rounded up and shot 75 of Castro’s men. Intervention by church friends in Santiago saved the Castro boys.

Months in Solitary. Fidel’s trial, on charges of leading an armed uprising, was all that a lawyer-revolutionary could ask. Rising for a three-hour oration, Castro described the attack in fearless detail, diagnosed Cuba’s social ills—”The 900,000 farmers and workers, miserably exploited, with perennial work their only future and the grave their only rest.” He denounced Batista’s corruption and tyranny: “We were born in a free country, and we would rather see this island sink to the bottom of the ocean than consent to be anybody’s slave.” Concluding, he said: “I know that for me imprisonment will be harder than it ever was for anyone, but I do not fear it, as I do not fear the fury of the miserable tyrant who killed my brothers. Condemn me! It does not matter! History will absolve me!” The judge, unmoved, sentenced Fidel to 15 years. Raul to 13.

Fidel served seven months in solitary confinement on the Isle of Pines, passing the time by memorizing an English dictionary. His wife, whose father had become a Cabinet minister’s aide, divorced him. Then Batista, cocky and prosperous, declared an amnesty in 1955 for political prisoners, including Castro.

Castro went to Mexico to recruit men and money. One summer evening in 1956, he stole across the Rio Grande near McAllen, Texas. Castro spent the next day in McAllen’s Casa de Palmas Hotel with the richest Batista-hater of all: ex-President Carlos Prío Socarrás, 55, who had been bounced from office by the dictator’s coup eight months before his term was up and began plotting so persistently that he is still under U.S. indictment for violating the Neutrality Act. “Here was the timber of a hero,” said Pro. As President, Prío had grafted a fortune; he promised to back Castro with arms and cash.

Back in Mexico City, Castro, called on Spanish Colonel Alberto Bayo, onetime fighter against Franco. Said Castro: “You know all about guerrillas. You will teach us.” Bayo sold his furniture factory, rented a big hacienda in the shadow of the volcano Popocatepetl, and taught hit-and-run warfare to 80-odd irregulars assembled by Castro.

“Well,” said Fidel one day, “you are telling us tactics for cowards.” “No,” said Bayo, “for intelligent people. You cannot go in there and face 21,000 well-equipped troops in open battle. You are going to be there like mosquitoes. Your attack on Moncada was & big mistake.” Castro, who had already named his movement “26th of July” for the date of the Moncada attack, was hurt. But he force-marched his rebels through the mountains 15 hours a day, learned mapmaking, bomb making and marksmanship. On Nov. 26, 1956, Castro and 81 revolutionaries set to sea from Tuxpam on the Gulf of Mexico aboard their Prío-bought 62-ft. yacht Gramma.

Decimation. Six days later Castro landed on the southern shore of Oriente province, to be met by Batista’s 1st Regiment. Only a dozen rebels escaped the slaughter. Among them were Cuba’s future leaders: Fidel and Raul Castro, an Argentine surgeon named Ernesto (“Che”) Guevara, a onetime New York dishwasher named Camilo Cienfuegos, a Havana rebel named Faustino Perez.

Twenty days’ march from the beach, the few remaining rebels reached blessed refuge in the Sierra Maestra, a wilderness of sheer cliffs, snarled liana vines and pockets of thick, orange mud. Batista, in a fatal mistake, overconfidently withdrew his troops. Castro and his men lived on plantains and mangos—and waited. The first break came from Jose (“Pepe”) Figueres, President of Costa Rica, 800 miles to the southwest. To a hastily cleared Sierra airstrip, Socialist Figueres sent a twin-engined Beechcraft loaded with rifles, Tommy guns, ammunition and grenades. “I felt sorry for that man,” Pepe explained.

Again and again Batista’s army announced that “the campaign is almost won.” But his 1,000 barracks-fat soldiers around the Sierra Maestra showed less and less hunger for the fight. In the long stalemate the rebel army grew in size and fervor. Castro talked and talked of his dreams for Cuba, sitting up until dawn in the huts of the guajíros—the squatters who farm the rugged mountains. “It is not right,” he said, “that a man should go to prison for robbery when he is able to work, wants to work and cannot find a job.” The guajíros nodded gravely and joined up.

Pressagentry. Castro showed a natural flair for publicity. Rebel beards, originally grown for lack of shaving gear, gave the revolt a trademark. Astigmatic from birth, Castro was seldom caught with his spectacles on. “A leader does not wear glasses,” he said.

Newsmen from all over the world rated top priority with rebel couriers, who escorted them into the hills. For his 1957 interview with New York Timesman Herbert Matthews, Castro made a dangerous trip to the foothills, got invaluable publicity from the U.S.’s most prestigious paper. Other reporters, getting past army checkpoints as “engineer” or “sugar planter,” had to make an arduous climb, but they were rewarded with long, friendly chats. To oblige CBS, the rebels took in 160 lbs. of television equipment. One big-paper correspondent on his way up was crestfallen to discover a reporter from Boy’s Life on his way down.

The Underground. The new hope nourished a deadly and dedicated underground in and out of Cuba, devoted to terror, arms smuggling, espionage, fund raising. The rebels planted bombs in Havana, sometimes 100 in a night, in gambling joints, movie houses. The police and Batista’s dreaded Military Intelligence Service counter-terrorized Cuba by killing suspected underground members, leaving their bodies on busy sidewalks to be seen by stenographers going to work. In reprisal a Santiago mother placed a wreath at night on the exact spot where her son was slain. An arrogant cop kicked the flowers away next morning and was blown to bits by the bomb beneath.

Abroad, rebel sympathizers perfected means for buying and smuggling arms. Castro’s brother Raul, commanding a column of recruits as big as Fidel’s, kept an airstrip open on mountain pastures. By spring of 1958 arms flights became big and frequent—notably from rich Venezuela, which had just thrown off a dictatorship. Cubans in Florida regularly flew planeloads of arms from small airports in Broward County and at Ocala and Lakeland, once made a fire-bomb run.

The arms were whatever the world’s dealers had to offer—Italian sporting rifles, ancient Mausers, nickel-plated revolvers, Springfields, Garands and carbines. Delivered, they cost an average of $1,000 each. Castro handled each munitions shipment with care and glee before passing it on to new recruits. “Bullets come by vintages, like wine,” he explained, “especially Latin American bullets. Mexican ’55 is a good year, ’52 not so good.”

To buy arms, the rebels had money to spare. Collections in the U.S. came to $25,000 a month. Rich Havana sympathizers donated as much as $50,000 each, and the dues from the Havana underground yielded another $25,000 monthly. Contributions and nonredeemable “bond issues” in Venezuela raised $200.000. Companies operating in eastern Cuba began paying “taxes” to the rebels. As a hedge against the future. Sugar Baron Julio Lobo, one of Cuba’s richest men, kicked in $100,000.

Toward the end of 1958, the rebels began moving west. Ex-Dishwasher Camilo Cienfuegos marched a column into the hills of Camagŭey. In December the rebels launched a “battle for Santa Clara”-a city of 150,000 in Las Villas. A column led by Che Guevara quickly took the streets, the Batista army as quickly retreated to its fortress post, and in five days of shooting 60 died.

The rebels knew that they were gaining, but they did not realize that victory was so close at hand. On Christmas Eve a priest climbed the hills to report to Castro that General Eulogio Cantillo, commander of Moncada Barracks, would like to have a chat. Castro celebrated by coming down to the family farm at Mayari, his first visit in four years. “Oh, what a party we had that night!” says his mother. “His soldiers were all over the place, and he bought $1,000 worth of beef to feed the people from all around.”

Triumphal Sweep. A week later Batista ignominiously fled to Dominican Republic exile, and his army surrendered. Rebel Commanders Guevara and Cienfuegos sped into Havana in captured tanks and took over the key garrisons, Cabana Fortress and Camp Columbia. For the next week Fidel Castro received the ovation of his islanders in a triumphal westward sweep. Even before he reached Havana, the record shops were selling a new guaracha:

Fidel has arrived,

Fidel has arrived.

Now we Cubans are freed

From the claws of the tyrant.

Fidel Castro had won by following Colonel Bayo’s instructions almost to the letter. In a much publicized war, his small attacks and quick withdrawals held rebel casualties to a mere 250 men—less than the U.S. traffic toll over the New Year weekend—and he had taken only about 400 enemy lives at the front.

In his first post-victory action, Castro distributed the top army commands to Gramma veterans: Raul Castro in Santiago, Cienfuegos at Havana’s Camp Columbia, Che Guevara at Cabana Fortress.

Preaching the Dream. Castro himself took to balconies and street corners for a marathon of three-hour orations, endlessly repeating his visionary plans to “purify” Cuba. “I want to go back to the Sierra Maestra,” he said, “and build roads and hospitals and a school-city for 20,000 children. We must have teachers—a heroine in every classroom.” He promised a homestead law to give the guajiro squatters title to the poor mountain plots they farm. The army would be a “people’s army” built around los barbudos, the bearded veterans from the hills. He even had ideas on diet: “The silliest thing I know is that Cubans eat so much meat and so little fish.”

Purification will give way slightly to the demands of U.S. tourists. Castro promised that he would allow the big casinos to reopen—but for tourists only, and without the U.S. mobsters who ran them for Batista. He said he would turn the national lottery into a kind of savings-and-loan association to cure the “improvidence” of the Cuban people. The Mambo Club is still open, but the prettiest girls have fled. At Madame Cuca’s, a blondined, buxom wench hoped that “Fidel will never close us, but if he does, we will take to the streets. We could form a new underground.” The theaters that used to specialize in wide-screen Technicolor pornographic movies closed up.

The most encouraging signpost in three turbulent weeks was the Cabinet appointed by Provisional President Manuel Urrutia. They were mostly responsible, moderate men, ready to get to work:

¶ José MirÓ Cardona, 56, dean of the Havana Bar Association, became Urrutia’s Prime Minister and right-hand man.

¶ Rufo LÓpez Fresquet, respected economist and a top rebel moneyman in Havana, took over the national treasury. He found it considerably diminished by the $210 million that Batista spent on the war, but backed by a sound economy. To help meet bills, a group of U.S. companies paid taxes of $3,000,000 in advance.

¶ Roberto Agramonte, 54, a former ambassador to Mexico and a favored candidate in the 1952 elections canceled by Batista, became Minister of State.

¶ Faustíno Pérez, a bearded Gramma survivor, traded his uniform for natty civilian clothes and the title of Minister for Recovering Stolen Government Property. As a start he took inventory at Batista’s estate outside Havana—mansion, movie house, museum, library, $4,000 lamps.

If these men have their way, they will not cripple Cuba’s sugar-based economy by drastic agrarian reform. They will keep the climate warm for U.S. investors, whose $800 million stake in Cuba includes huge plantations producing 40% of the sugar. In turn. Cuba will keep its big, guaranteed share of the U.S. sugar market. A dozen U.S. industries in Cuba, including Firestone, Du Pont, Reynolds, Phelps Dodge and Remington Rand, finished plants last year, and other big firms are going ahead with building plans.

Communists, strong in the new labor organization but weak elsewhere, will try to stir anti-U.S. hatreds. Che Guevara, a frank proCommunist, will give Communism all the help he can in the new army. A Communist-lining journalist, Carlos Franqui, is in a powerful spot as editor of the official rebel newspaper, Revolución. But Cubans know the U.S. too well to swallow the usual Communist whoppers. Any party that wins free elections in Cuba will doubtless be in the Western camp.

Castro is on the record with a promise of free elections a long 18 months or two years from now. “The parties must have time to reorganize,” he argued. “If we held elections tomorrow, we would win. People tire quickly. In 18 months, the people may be very tired of us.” Castro led a revolution against personal government and for restoring a rule of law; since the date of his victory, he has built a government based largely on his personality, while his men have violated his country’s basic law. If he can summon maturity and seriousness, the bloody events of last week may yet turn out to be what Puerto Rico’s Muñoz Marin thinks they are: “A bad thing happening in the midst of a great thing.” If not, the seeds of hate sown in the execution ditches will sprout like the Biblical tares.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com