The Biblical story of Exodus hits the big screen on Friday with the release of Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings. The story is one of the most timeless in Western history, like the Odyssey or Shakespeare, only imbued with deeper spiritual significance, as Jews, Christians, and Muslims all claim the hero as their own. This newest adaptation is classic Scott-style, very Gladiator, set in an ancient Egypt where Ramses is Pharaoh and Moses is Christian Bale.

Like any retelling of a classic, Scott’s blockbuster invites questions about the Exodus’ story’s origin and meaning. Most of the basic plot elements of the Biblical story are included in the film’s adaptation—Moses is a Hebrew boy raised in Pharaoh’s house, he leaves Egypt and encounters the divine in a burning bush; he returns to Egypt to free God’s people from slavery under Pharaoh; there are a bunch of horrible plagues; and the Red Sea parts so the Hebrew people can escape Pharaoh’s armies.

From a strictly historical perspective, the Biblical Exodus story is murky at best. While there is some evidence that a people named Israel were emerging in Egypt in the late 13th and early 12th centuries BCE, little information exists about Israel’s presence there during the time. The general picture is clearer—Egyptians were in power in the region most of the time, various people groups migrated to Egypt during times of famine because the Nile made Egypt’s agricultural system more stable, and slavery was a part of the economic system of the ancient world. Most likely multiple people groups would have been enslaved, not just Semitic peoples, as slaves were often debt slaves or prisoners of war.

Ten Actors Who Have Played God (In Film)

The origins of the written account of the Exodus story in the Bible are equally hard to pin down. “We don’t know when it was written, by whom, and it appears to come from multiple traditions in Israel which were probably both oral and written traditions and probably developed over centuries,” explains Ellen Davis, professor of Bible and practical theology at Duke Divinity School.

But drilling the Biblical story for proof of its narrative elements—that the Red Sea split, the Nile turned to blood, that flies attacked and frogs covered the land—misses the poetic power of the story itself. The Bible as a whole is not designed as a history textbook. It is a collection of different types of writings. Some are historical records, others are laws, poems, prose, and prophecy—written over hundreds of years and in various cultures and languages. The core of the Exodus narrative is actually a song, recounted in Exodus chapter 15, and it is one of the oldest fragments of all Biblical texts, likely dating to the earliest period of Biblical literature. Songs, as Davis explains, are the kind of thing people pass on orally and remember. “Exodus 15 may well be one of the kernels out of which the book of Exodus as we have it grew over centuries in the process of oral and written traditions gradually getting consolidated,” she says.

The truth of the Exodus story is poetic—it is the quintessential story of oppression and liberation. The Pharaoh of Exodus, Davis points out, is not named. “It is, you might say, the generic Pharaoh,” she says. “There is a deliberate lack of specification. Pharaoh is the sort of quintessential oppressive ruler in the Bible, and that is how he is remembered in later literature, so he stands for the oppressor of the moment in a sense.”

That is one reason the narrative has resonated powerfully generation after generation—there is not just one Exodus story. “Let my people go” is a timeless refrain for redemption. It is at the core of the African-American religious traditions in the United States. In some parts of the world, the Exodus story still is very concrete. Davis worked in South Sudan with the Episcopal Church a few weeks before the new state was declared in July 2011. Women is the region often carry babies in baskets on their heads, and many of the people she works with, she says, have seen baby baskets torn from women’s heads and boy babies thrown in the Nile—the river runs through South Sudan. “They don’t want those boy babies to grow up and be soldiers,” Davis explains. “It is not a story that disappears.”

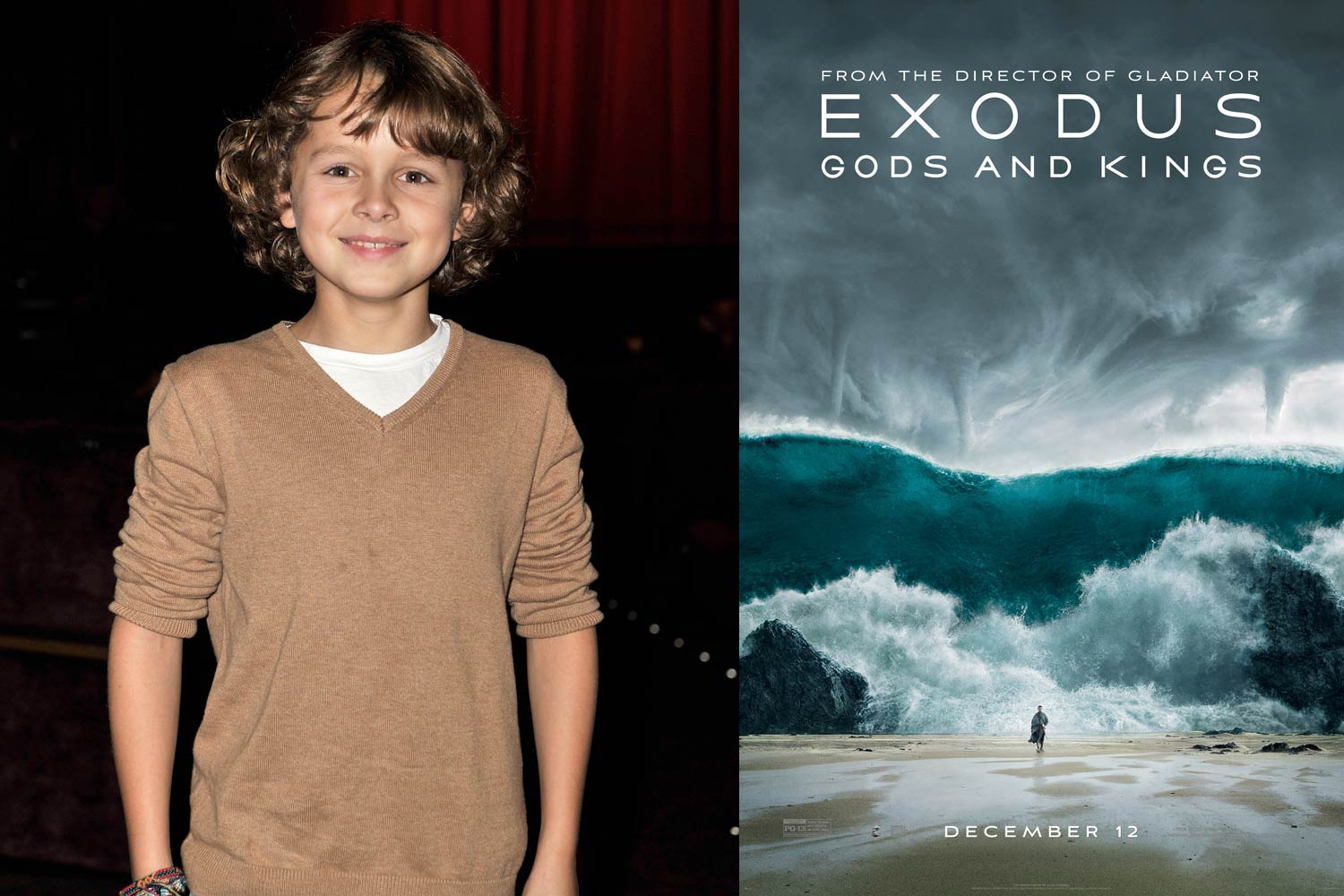

One of the most striking aspects of Scott’s Exodus is that God is portrayed as young boy. Eleven-year-old Isaac Andrews plays the God character, and the choice is both brilliant and scary. It plays on Scriptural images about becoming like a child to enter the kingdom of heaven and—with the Christmas time release—it makes it impossible to forget that God being born as a child is the New Testament’s own liberation story. But the film’s God-child is also more King Joffrey than let-the-little-children-come-unto-me. He actively inflicts plagues of frogs, gnats and boils upon the Egyptian people, and ultimately kills the first-born of all Egyptian families. It is impossible to escape the irony—a child becomes the killer of children.

That raises questions of what kind of God the God of Exodus really is. The film purposefully papers over whether Moses is imagining the child-God, if he is having a vision, or if he is mentally unwell. The Biblical narrative of Exodus portrays God as a king and a man of war—the main drama, Davis explains, is a battle over sovereignty between Pharaoh and Israel’s God.

“You have to remember that Israel was most of the time in its history in a situation of being oppressed, and if you are an oppressed people, it is good news to know that God is going to render judgment, because you are not worried about God’s judgment nearly so much as you are worried about what is going to happen to you from the oppressor,” Davis says. “People have always understood that ultimately God renders judgment and brings down the powerful and raises up the lowly, and you have that in the New Testament just as much as you have it in the Old, that has always been viewed as good news.”

And spiritual questions like these are the ones that never go away, which means Scott’s version of the Exodus story won’t be the last, no matter what happens at the box office.

Read next: Ridley Scott Explains Why He Cast White Actors In Exodus: Gods and Kings

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com