Suppose you are a President who has just witnessed 3,000 American deaths in a terrorist attack by a shadowy enemy. Intelligence strongly indicates that follow-on attacks will come. You have little information on future attacks, but you know that the enemy will employ unconventional tactics that violate the very laws of war. The enemy disguises its operatives as civilians, it attacks civilians and peaceful targets by surprise, and is willing to use any weapons, including chemical and biological. Then, just a few months after the attacks, an amazing stroke of good fortune falls into your lap: The U.S. captures the first high-ranking leader of the enemy.

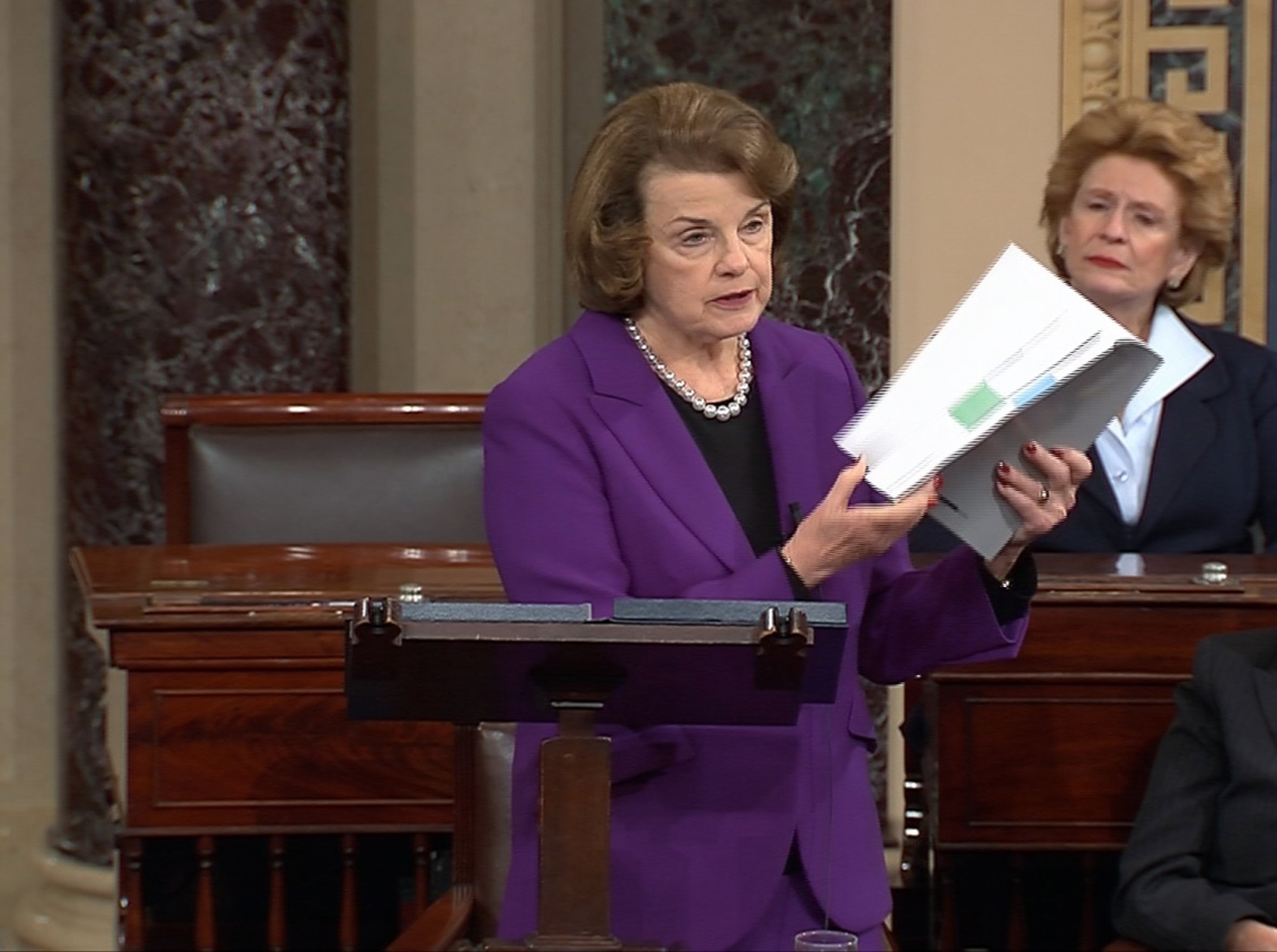

What would you do? According to Senator Dianne Feinstein’s report on Bush-era interrogation policies, released today, you should allow only police station-style questioning. Designed to build a rapport between the interrogator and the detainee, these methods can take weeks, if not months, if they work at all. If al Qaeda leaders refuse to cooperate, the CIA and FBI will have to wait. You cannot treat them differently, the Feinstein report implies; you must give them the same benefits that our Constitution reserves for American citizens suspected of garden variety, domestic crimes. If another attack occurs, perhaps worse than the first, the President must still wait for the al Qaeda leaders to cooperate willingly.

Any President who followed Feinstein’s advice would fail in his or her fundamental duty to protect the security of the United States. A President charged with this responsibility cannot wait weeks, months, or never; he must obtain intelligence as soon as possible to stop the next attack. Under these emergency conditions, a chief executive would reasonably give the green light to limited, but aggressive interrogation methods that did not cause any long-term or permanent injury. You might even approve waterboarding in the time of emergency (remember, again, that this is three months after the attacks) if limited only to enemy leaders thought to have information about pending attacks.

As a member of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel at the time of the 9/11 attacks, I thought that the CIA’s proposed interrogation methods were within the bounds of the law—just barely. They did not inflict serious, long-term pain or suffering, as prohibited by the federal statute banning torture. We realized then that waterboarding came closest to the line. But the fact that the U.S. military has used it to train thousands of U.S. airmen, officers, and soldiers without harm indicated that it didn’t constitute torture. Limiting tough interrogation methods only to al Qaeda leaders thought to have actionable information, during a time when the nation was under attack, further underscored the measured, narrow nature of President Bush’s decision.

The Feinstein report cannot deny that most Americans agree President Bush acted reasonably under these emergency conditions. Indeed, if the American people concluded that Bush had made a grave mistake, it could have turned him out of office in the 2004 elections (which took place after the stories about tough interrogations first leaked). And the Feinstein report cannot deny the record of success. Armed with intelligence from interrogations, electronic surveillance, and sources on the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Bush and Obama administrations have so far prevented another massive al Qaeda attack on the U.S. homeland. Any terrorism expert inside or outside of government in Fall, 2001 would have been astounded at this result in light of the openness of American society and al Qaeda’s track record. For many years, interrogations yielded the great majority of intelligence that the U.S. held on al Qaeda, which allowed the CIA and the U.S. military to carry out operations that have devastated the terrorist group. (If you don’t believe me, take a look at the 9/11 Commission Report’s footnotes. Most of its important information on al Qaeda comes from interrogations.)

Feinstein can only deny the reasonableness of the choices made in the aftermath of 9/11 by claiming that they never worked. With imperfect hindsight, her report claims that the CIA lied to induce President Bush to order aggressive interrogation methods and then did not produce any unique, actionable intelligence. Worse yet, it alleges that the CIA lied to the White House, the National Security Council, the Justice Department, and Congress about interrogations to exaggerate the intelligence gains and to downplay the harms to al Qaeda detainees.

Such a claim simply does not stand up to the truth. The Feinstein report contains a record of mistakes made by CIA agents in the field, miscommunications between officers and headquarters, and misunderstandings between CIA officials and the White House and Justice Department. But it does not show that the interrogations were a failure. It shows anything but. There are two cases that leap out upon even a cursory reading of the report.

First, and most important of all, the report and the CIA dispute whether interrogations led to the location of Osama bin Laden. CIA directors have said publicly that the information identified the courier, a fellow named Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, and that tracking him led us to bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. The Feinstein report claims that it found the name of the courier in CIA files from other, independent sources. But this is a red herring. The CIA had the names of hundreds, if not thousands, of possible al Qaeda operatives in its databases. Only the interrogation of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the planner of the 9/11 attacks, and other al Qaeda figures explained al-Kuwaiti’s significance. Without their interrogations, the al-Kuwaiti lead could have languished in the “for follow-up” file forever.

Second, the Feinstein report cannot explain the successes in 2002-04 in dismantling the al Qaeda leadership. After the late 2001 capture of al Qaeda facilitator Abu Zubaida, whose refusal to cooperate first raised the question of interrogation methods, the U.S. ran the table: It captured al Qaeda mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, his deputy Ramzi Binalshibh, and an Indonesian named Hambali who was planning a 9/11 style airplane attack on the West Coast, among many others. Without a doubt, these losses disrupted al Qaeda’s efforts to carry out follow on attacks in the United States and degraded the terrorist group’s ability to organize and operate.

The Feinstein Report claims that the CIA would have captured all of these operatives anyway. The Senator from California forgets Yogi Berra’s saying: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Feinstein provides no reason to conclude, counter-factually, that the U.S. would have killed or captured these al Qaeda leaders without the high-quality intelligence from interrogations. The United States and its allies certainly had not done so before the interrogations started—it did not even know about many of them before 9/11. But we do know that armed with the intelligence from interrogations, the U.S. succeeded.

Today’s release of the Feinstein Report will only reignite partisan fighting over the best tactics to fight terrorism. Excluding Republican Senators and their staff in the investigation and refusing to interview any of the CIA and White House officials involved clearly shows the bias inherent in the investigation. The Senator from California thought her mission was to pursue officials with whom she disagreed, rather than issue a fair, impartial review of the Bush-era programs. Her report can only undermine the ability of our intelligence agencies to protect our nation as ISIS controls wide swaths of Iraq and Syria, terrorists behead American citizens taken hostage, and the administration suffers one intelligence setback after another.

John Yoo is a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley and a scholar with the American Enterprise Institute. From 2001-03, he worked in the Bush Justice Department on interrogation and other legal issues raised by the 9/11 attacks.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com