This post originally appeared on Consequence of Sound.

In the current Hollywood climate, the lust for franchises is at an all-time high. It’s a logical enough response to both the difficulties found in getting the average American viewer into a theater in the past few years, and the never-brighter future of the new, globalized audience for Hollywood tentpole features. In both cases, name recognition is the most logical (if not necessarily the most ideal) means to get people back in seats. For all the theatrical gimmickry that chains have rolled out in recent years (dine-in screenings, electric recliners, flight simulator-style seating), there’s perhaps nothing more verifiable when it comes to packing a house than a continuation of another film that people saw and enjoyed. Consider that of 2014’s top 10 highest-grossing films so far, as of this writing, six are sequels. Of the other four, you have two modern reboots of famed existing characters (Maleficent, Godzilla), a new entry into an existing franchise model (Guardians of the Galaxy), and The LEGO Movie, a surprisingly enjoyable film that’s nevertheless still based on a line of toys.

In the midst of Hollywood’s seemingly endless franchise hunt, one of the most prevalent trends of the past decade has been the renewed interest in the constant adaptation of popular young adult novels. It’s a logical enough approach; rather than greenlighting a film that’ll ideally spawn sequels, you pick up a property with a built-in following and a pre-released series of follow-up installments. Grab the next Hunger Games, and you have three or four movies ready to go from day one. In a recent article, I addressed just how many studios are trying to do exactly that, the latest Hollywood ideal being the next hot dystopian epic to follow Hunger Games, or the more recent successes of The Maze Runner and Divergent.

But what’s perhaps even more interesting than the handful of successfully launched YA adaptations in recent years is the massive volume of failures surrounding them. Vulture explored this question in brief last year, before the runaway success of Catching Fire, again primarily touching more heavily on the films that worked than those that didn’t. At one point, they quote YA publisher Ben Schrank, who explains that, “The fact that there are more people writing better books for young people than ever before, combined with a culture where fewer and fewer people think of themselves as old, makes over-saturation in the immediate future seem unlikely.” But this proliferation of books doesn’t necessarily mean that their popularity will translate; a book engenders a certain kind of more dedicated fandom by dint of its ability to establish a universe in far greater detail than the average 90-minute to two-hour film can muster.

So, back to the question at hand: why have so many adaptations failed? Vulture cites momentum at one point, which could explain Divergent and Maze Runner, especially the former; the market seems to be bullish on YA dystopian adaptations featuring popular young actresses in layered roles with peculiar first names for the time being. But it doesn’t entirely account for the phenomenon. After all, lest we forget (more on that momentarily), before Hunger Games it was Twilight. And it’s not as though studios didn’t try and fling their bodies onto that rapidly accelerating gravy train as well. But the fantasy market didn’t prove so lucrative. Between the time of the first Twilight film’s release in November 2008 and its conclusion with the underrated Breaking Dawn Part 2 in 2012, studios released at least seven other franchise hopefuls with YA pedigrees. Only one was sequelized, and even then, Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters underperformed in theaters last summer.

Even dystopia isn’t a complete guarantee; witness duds like The Host, another Stephenie Meyer offering that lacked source material for additional installments but still lent studios a sense of optimism. Or, more recently, Jeff Bridges’ long-gestating production of The Giver, as canonical a YA text as you can find in the present era, and a film which grossed less than $50 million. Films like The Giver and last year’s Ender’s Game aimed squarely for the YA audience, adult and young adult alike, and were based on classic novels that frequently appear on various schools’ English class reading lists, and yet both underperformed to the point where sequels are uncertain, verging on unlikely for the time being.

It’s curious to consider the string of flops in a few different respects, and one of them ties right back to Twilight. The oft-maligned vampire series was a cultural phenomenon upon arrival, the first film’s release having been perfectly timed with the release of the final installment of the printed series, Breaking Dawn. Of the top twenty highest-grossing YA adaptations to date, Twilight accounts for five of them. And yet, the buzz seems to have died down around the series. Sure, part of this can be written off as the innately ephemeral nature of most any popular trend; after a while, the collective consciousness moves on, and the series remains bound for an indeterminate time in that fiscally terrifying purgatory between initial popularity and nostalgic sentiment.

But with Twilight, it’s important to remember that the world started changing as the series progressed, and that series happened to be one major cog in a much larger evolution in American culture. One of the simultaneous booms and busts of the internet age is the ability for audiences to access criticism of their pop culture from every conceivable angle, and to discuss it ad nauseum with others. And given the eventual burnout on Twilight’s reductive gender roles and frequently interpreted moralizing, it makes sense that audiences were already getting enough of it from one source, and weren’t as interested in others. But it still found a crossover audience, which is more than can be said for Beautiful Creatures or The Mortal Instruments or I Am Number Four or City of Ember or Cirque Du Freak or Inkheart. But now, a show of hands: when’s the last time that dedicated Twi-hard in your life brought it up at a family gathering?

And with respect to the matter of audience saturation, that’s as much a sign of burnout as anything. People had their chosen franchise. They couldn’t invest in a dozen at once, because for those who weren’t already reading the books (another desired outcome of the franchise model), it was too much to take on. The proliferation of extremely similar material didn’t help, but the failed YA adaptations even precede Twilight. One of the most notable is still A Series of Unfortunate Events, the would-be Lemony Snicket franchise starter, that failed to see a second installment despite relative success compared to many of the flops that followed. And the burnout became ever more pronounced until last summer, when The Mortal Instruments, a film for which Sony had already kicked off pre-production on a follow-up, made less than $10 million in its opening weekend, on over 3,000 screens nationwide.

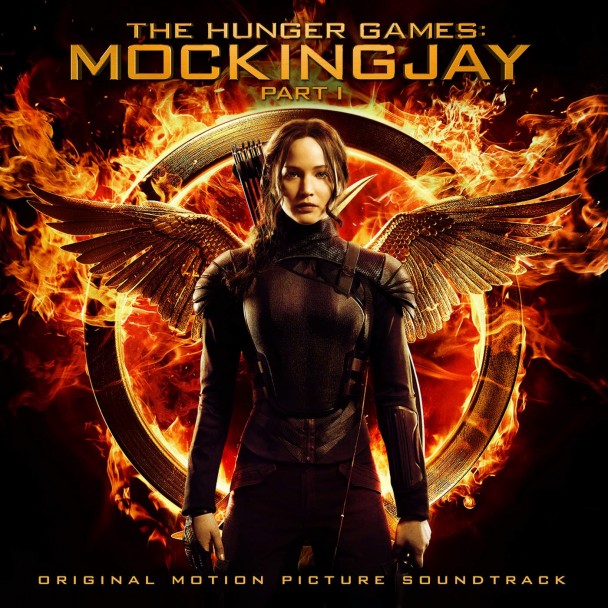

This year has seen them as well; even as Divergent was a breakout hit and Maze Runner found more moderate success, albeit with tepid critical and audience reactions alike, the popular franchise Vampire Academy was an unmitigated dud when released to little fanfare in the doldrums of February. It’s not that audiences are inherently uninterested; they just want something new. And studios aren’t going to stop pushing for the next big new thing. Properties are being snapped up one after the next, some of the current dystopian flavor and others attempting to break new ground and be the first to the party. The glut is hardly stopping, and even the existing franchises are trying to stretch as far as possible; like Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows and Breaking Dawn, this weekend sees the release of the first half of the two-part Hunger Games finale Mockingjay, and theDivergent series has already confirmed plans to split its final installment Allegiant in half.

A note on Potter, while the subject has arisen: it’s really those films that studios crave so desperately. While Twilight proved the buying power of the untapped young female demographic, Potter is the four-quadrant franchise to which others aspire. The Pottermodel was less one of a literary adaptation than it was the bellwether of what we’re seeing today with superhero franchises. Everybody saw them, and those who didn’t were still readily aware of their existence at all times. It was a market saturation, sure, but one people embraced. Perhaps what’s happening now, with the seeming disinterest in genre-based franchise offerings not focused on totalitarian governments, is the explosion of the bubble, the one that will inevitably implode in the case of most any pop trend. Buyers set out to find the next Potter, the next Twilight, the next Hunger Games, and they’re likely out to find the next one as we speak.

Dozens of novels have been picked up, and it’s unlikely that the glut ends before at least a few more fatted calves have been sacrificed to the cause. But eventually, the climate of the world will change again, and the interest in dystopia will transition into something else, something unpredictable and unsolvable by most metrics until it’s too late to get out ahead. This is the inherent downside of the YA boom, after all. You can pick a winner with a devoted following, a built-in series ready to go, and even come up with a catchy Twilight Saga-esque franchise subtitle for it all. But audiences will either show up or not, and by the time a movie even sees the light of day, it might already be too late to tap into the zeitgeist. Everybody’s headed for the promised West of the next Hunger Games, and even more will likely circle their wagons when Mockingjay likely starts printing its own money in a few days. But like any riches worth having, the millions conferred by a YA hit are for the few, not the many.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com