When Mike Nichols, who died on Wednesday at age 83, first gained notice, it was not as a director. In 1958, Nichols, then 26, appeared along with his comedy partner Elaine May, on NBC’s Omnibus revue; within six months, the two were touted by TIME as “the fastest-sharpening wits in television.” The two had met at the University of Chicago and began their dual career as sketch and improv comics in that city, as part of a group that would eventually feed into Second City.

Though they were an instant hit on TV, the question of how to translate their comedy to the censored and scripted world on screen. They found their footing on Broadway instead with An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, which debuted in 1960. “An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May,” TIME’s critic declared, “is one of the nicest ways to spend one.” From that point on, the rave reviews just kept coming.

By 1962, Nichols was acting in a play written by May, and in 1963 he directed Barefoot in the Park, earning another rave: “If the theater housing this comedy has an empty seat for the next couple of years, it will simply mean that someone has fallen out of it. Barefoot is detonatingly funny.” He would later tell TIME that it had been a turning point, the moment he realized he was meant to direct:

Nichols remembers: “The first day of rehearsal, I knew, my God, this is it! It is as though you have one eye, and you’re on a road and all of a sudden your eye lights up, and you look down and you know, ‘I’m an engine!’ ”

For his next Broadway foray, Luv, he earned the headline “The Nichols Touch” and was called “the sort of director whom most writers and actors only meet when they are asleep and dreaming.” As for 1965’s The Odd Couple, “[t]he only worry they leave in a playgoer’s head is how to catch his breath between laughs.”

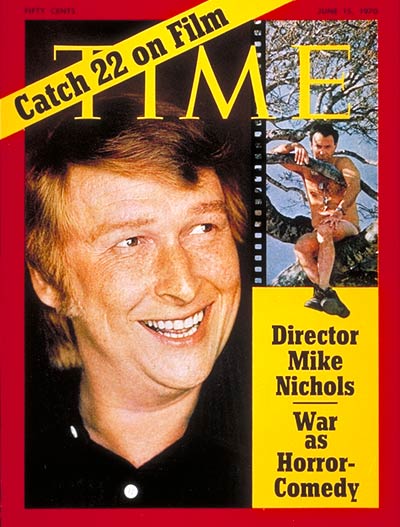

In 1966, when he made his first foray into movies with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the performance he got out of star Elizabeth Taylor was deemed “a sizeable victory.” By 1970, when he made a movie of Catch-22, he landed on the cover of the magazine, with a multi-page feature that praised the maturity of the work:

Fully loaded, the bombers take flight, make their lethal gyres and return empty. Under Nichols’ direction, the camera makes air as palpable as blood. In one long-lensed indelible shot, the sluggish bodies of the B-25s rise impossibly close to one another, great vulnerable chunks of aluminum shaking as they fight for altitude. Could the war truly have been fought in those preposterous crates? It could; it was. And the unused faces of the flyers, Orr, Nately, Aardvark, could they ever have been so young? They were: they are. Catch-22‘s insights penetrate the elliptical dialogue to show that wars are too often a children’s crusade, fought by boys not old enough to vote or, sometimes, to think.

Despite his much-acclaimed career — which would continue for decades — not every one of his projects won applause.

In 1967, for example, TIME gave one of his films a rare pan. The picture in question “unfortunately shows his success depleted” because “[m]ost of the film has an alarmingly derivative style, and much of it is secondhand” with “a disappointing touch of TV situation comedy.”

But, as befits a comedian by training, he had the last laugh: that movie was The Graduate.

Read the full cover 1970 story here, in TIME’s archives: Some Are More Yossarian Than Others

See Mike Nichols' Legendary Career in Photos

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com