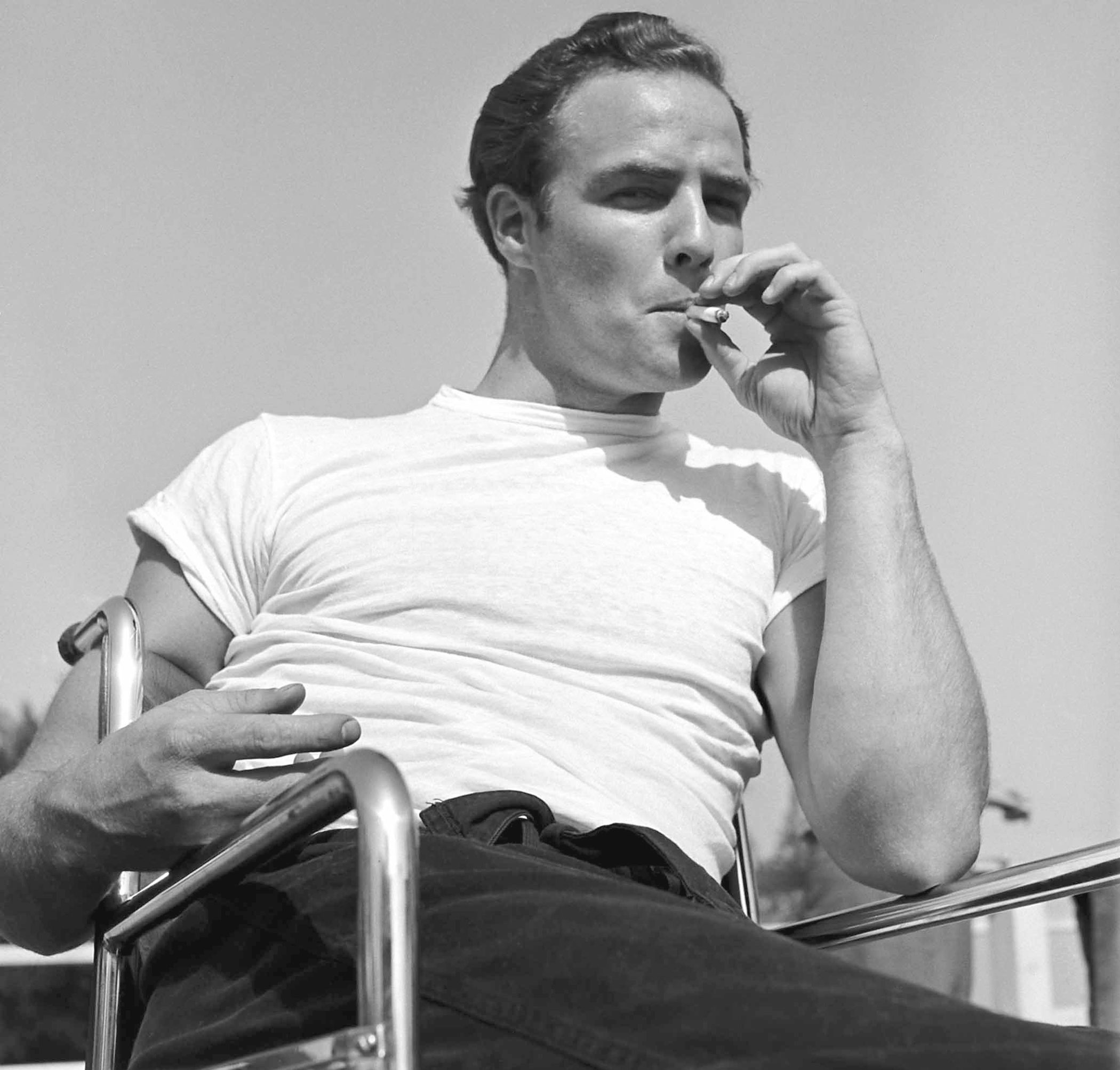

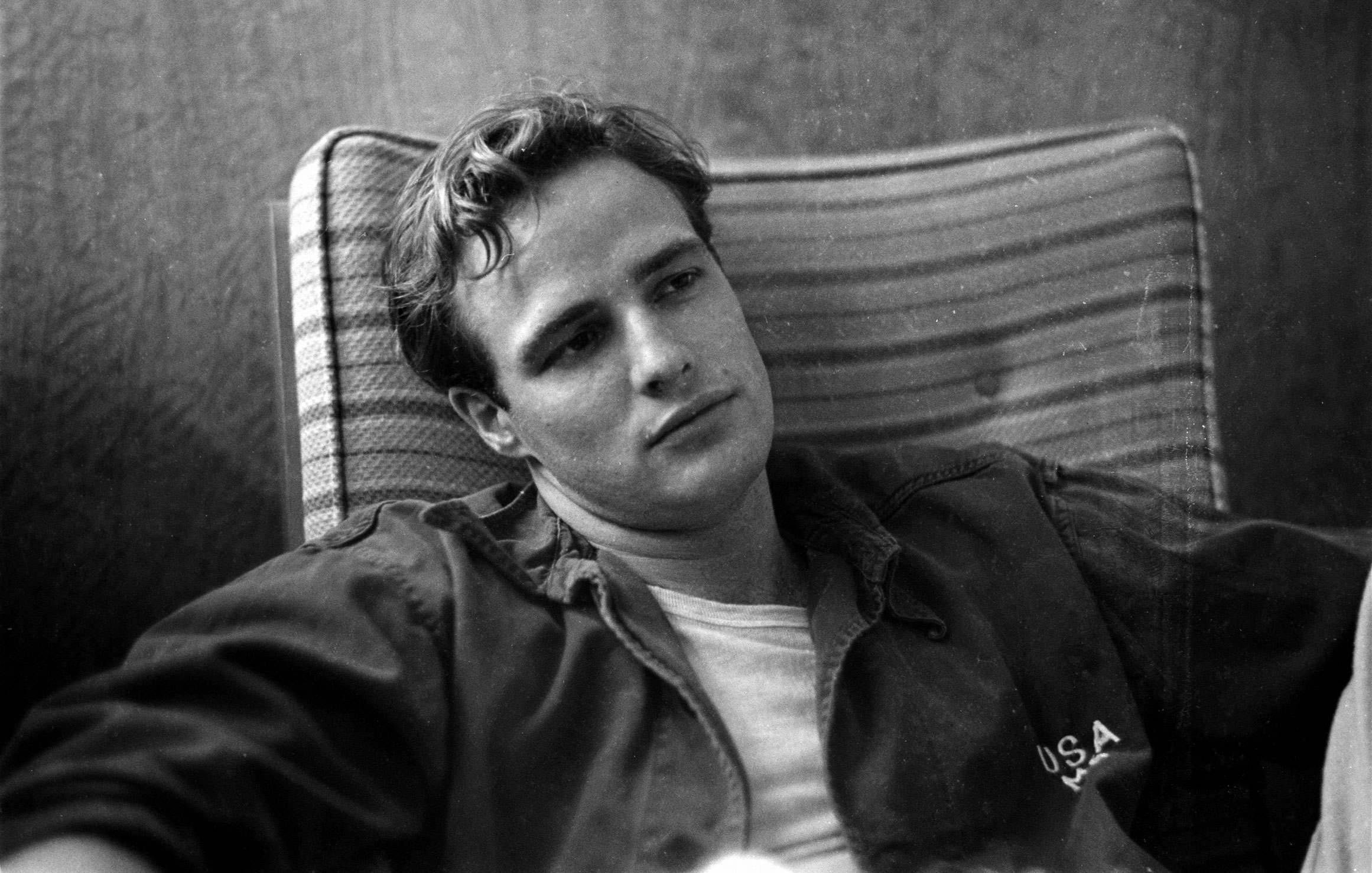

The year was 1949, and 25-year-old Marlon Brando — “the brilliant brat,” as LIFE magazine called him following his astonishing work on Broadway in A Streetcar Named Desire — had finally answered the call of Hollywood. He was preparing for his movie debut in The Men, the wrenching story of a paralyzed World War II vet coping with rage and insecurity. And while it’s true that Los Angeles was familiar with “Next Big Thing” newcomers, it was (and, to some extent, still is) exceedingly rare to document the earliest days in the career of an actor of Brando’s intensity, quirkiness and electrifying talent.

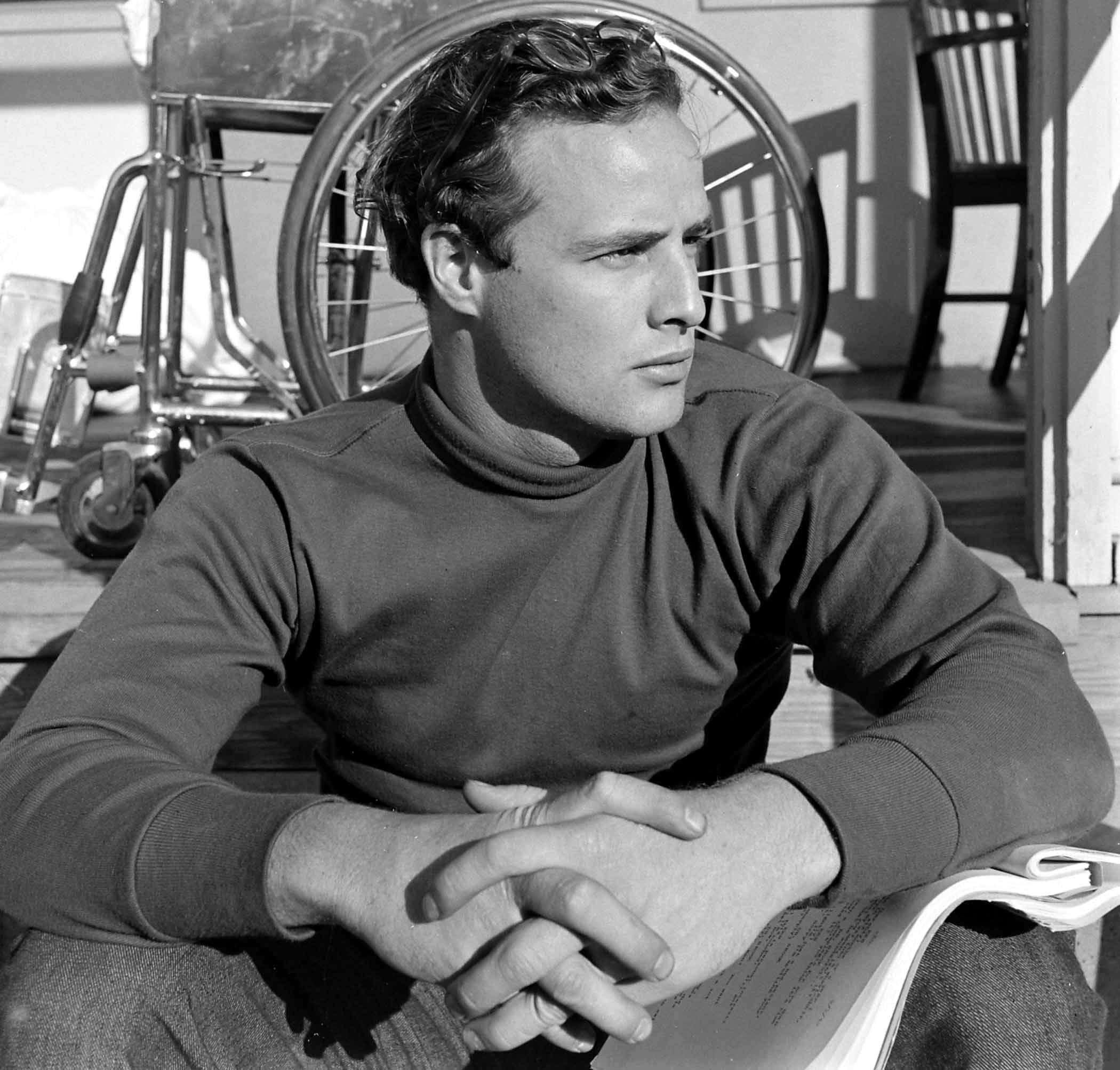

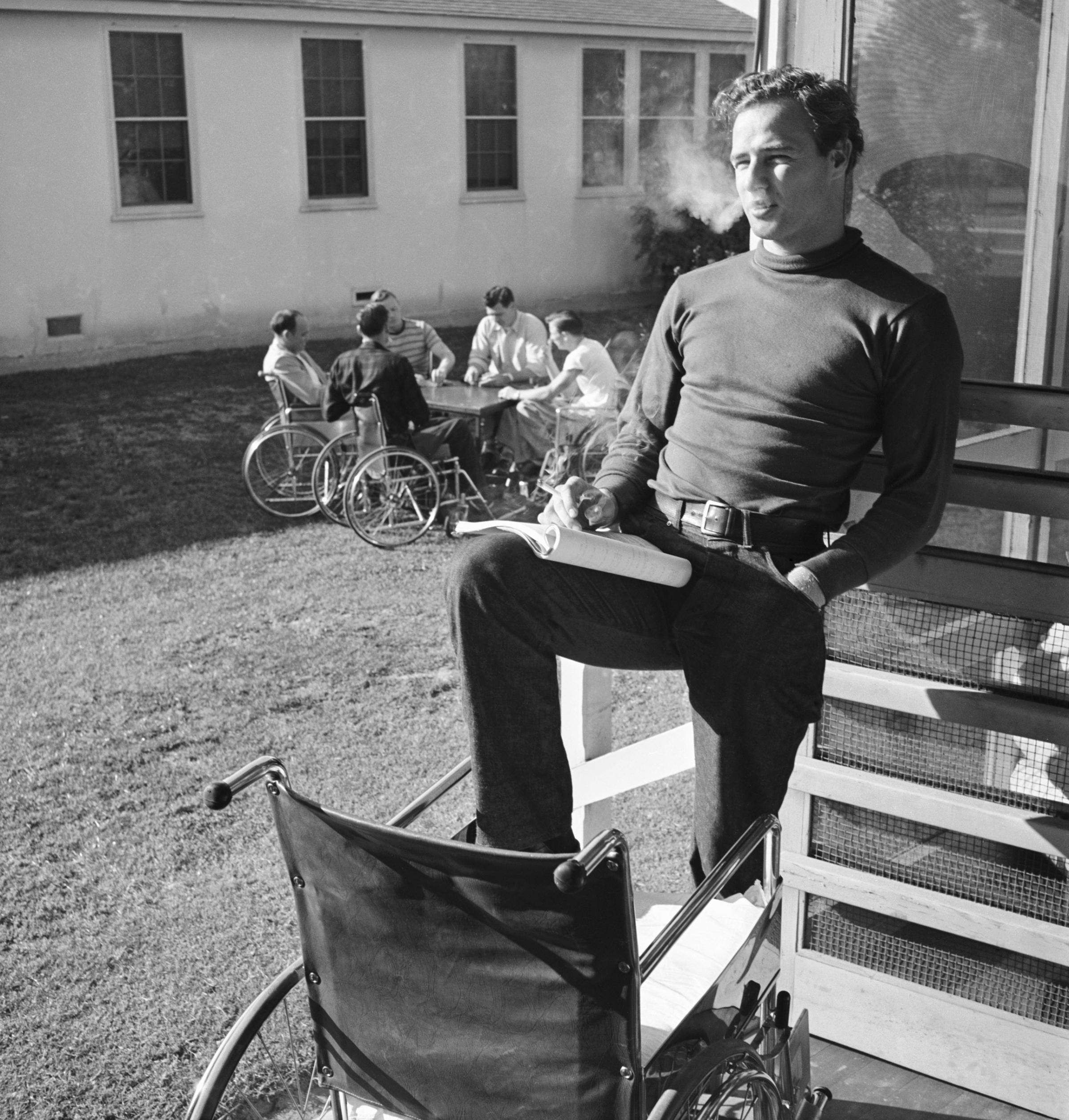

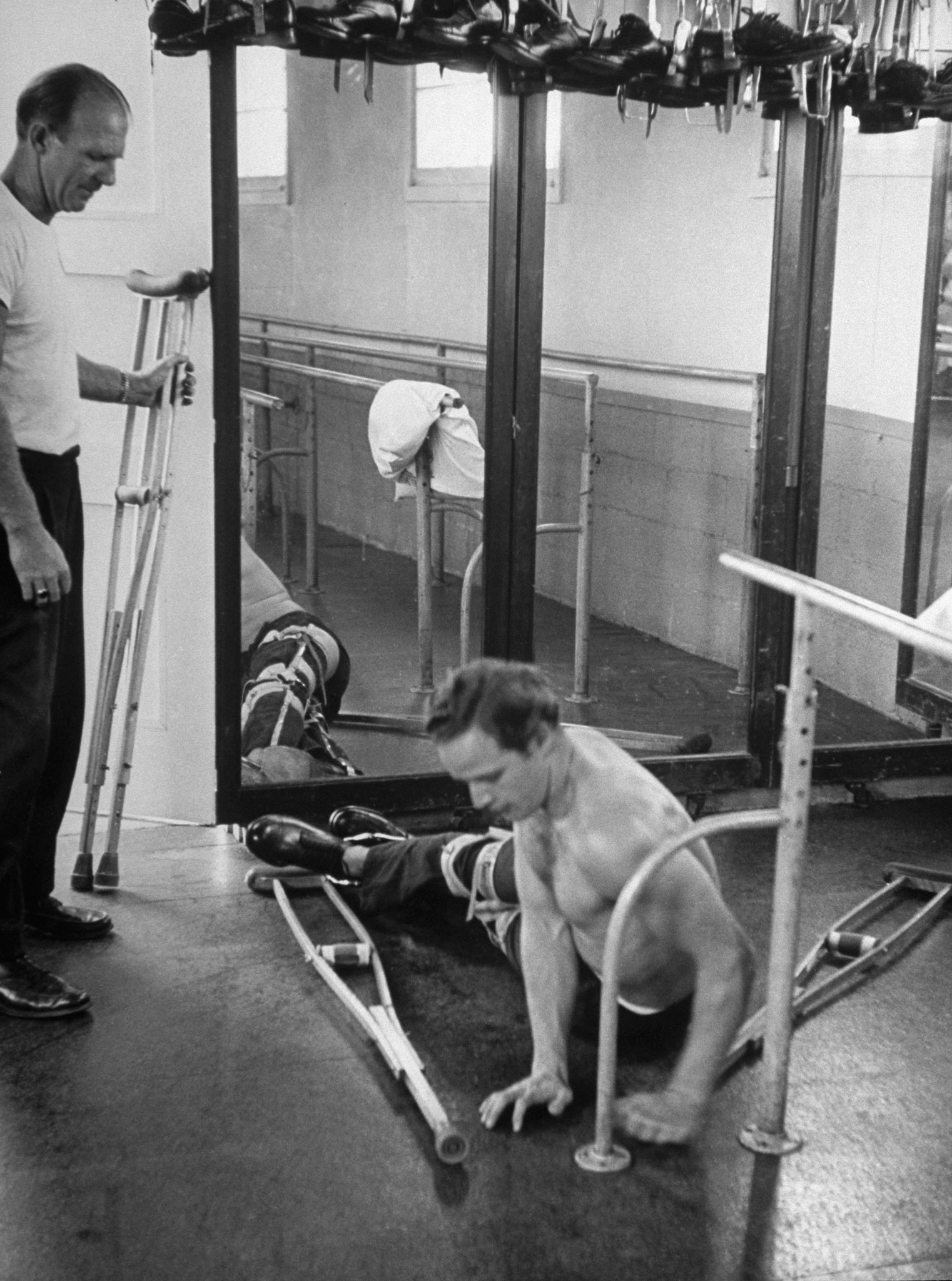

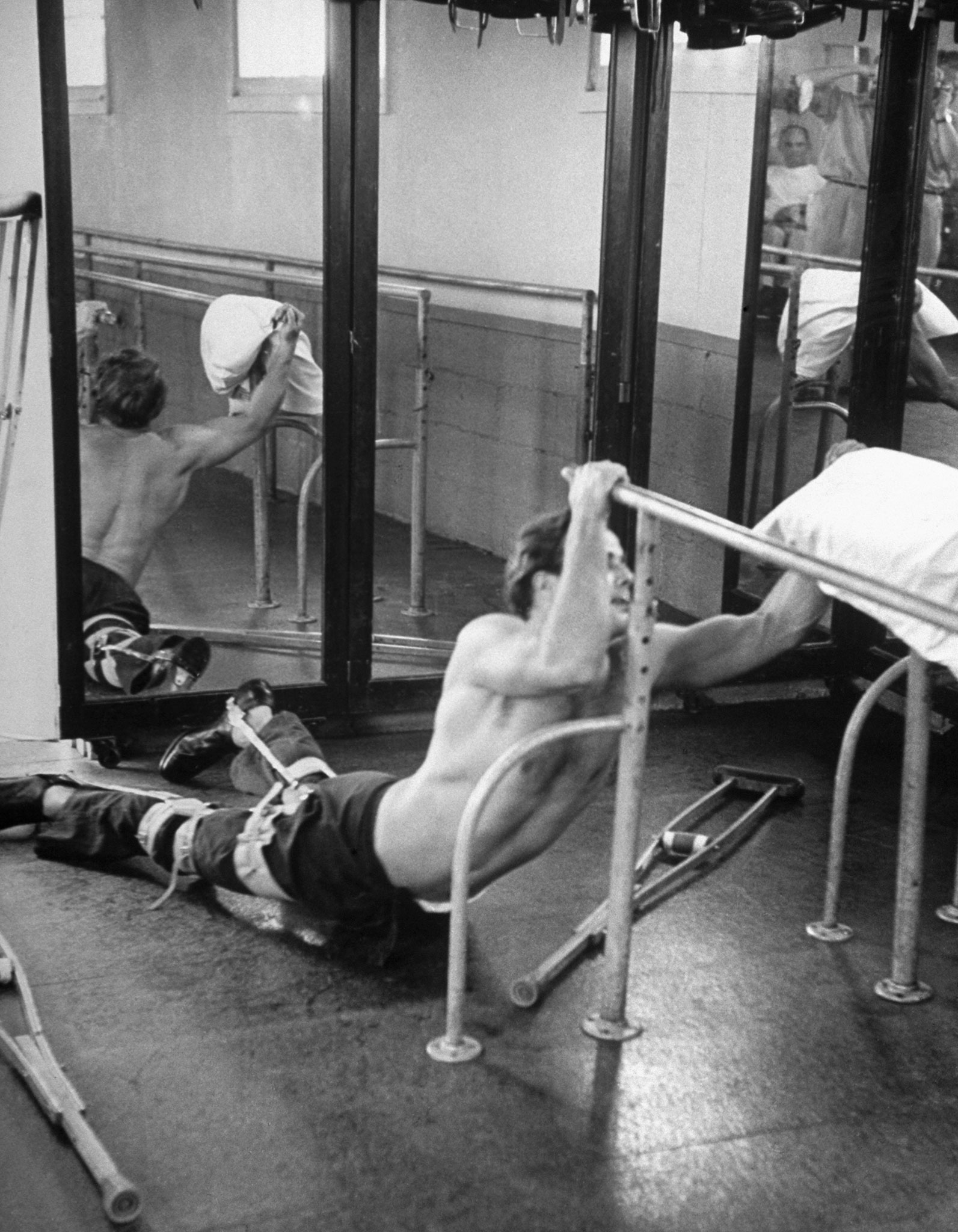

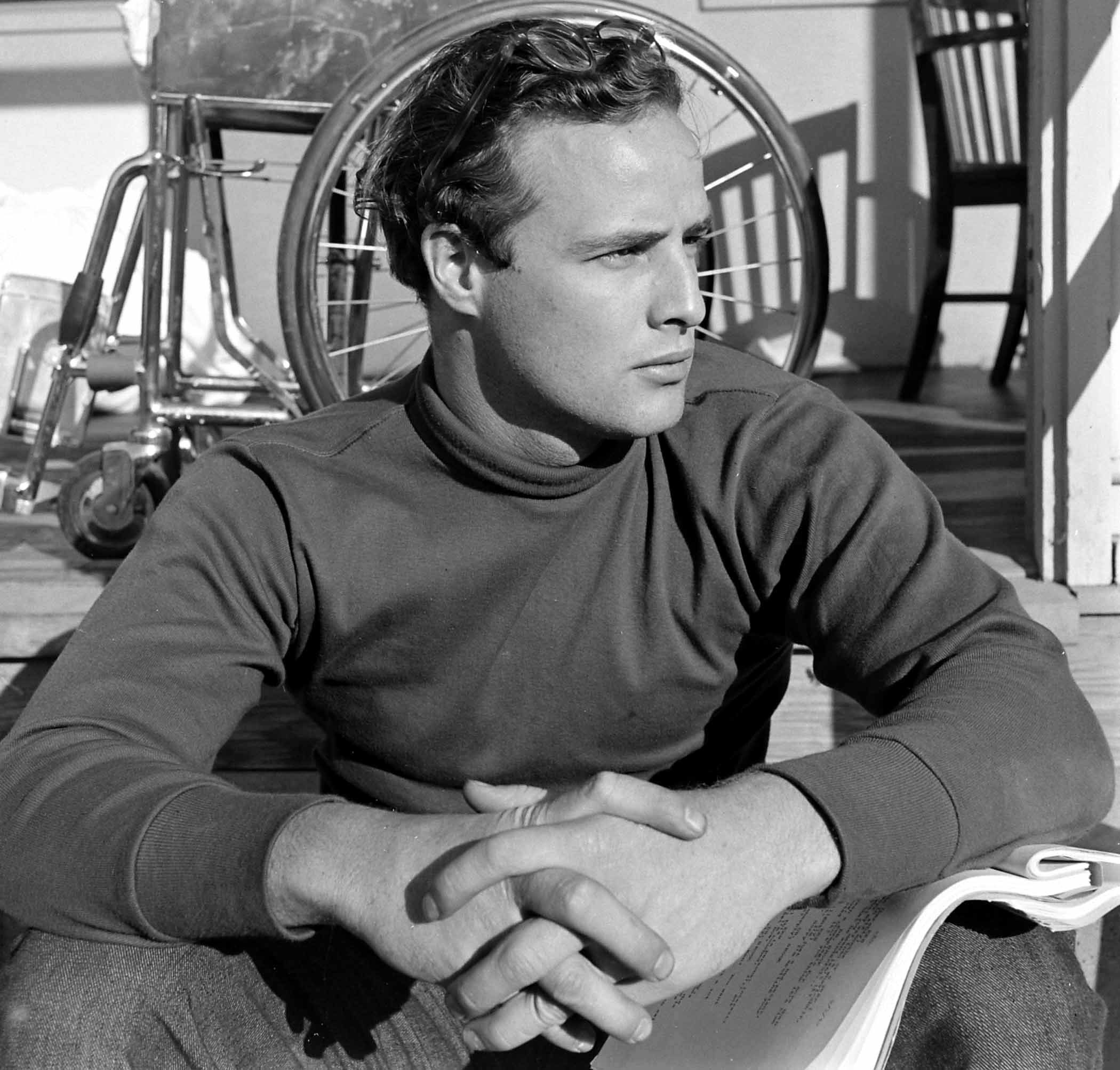

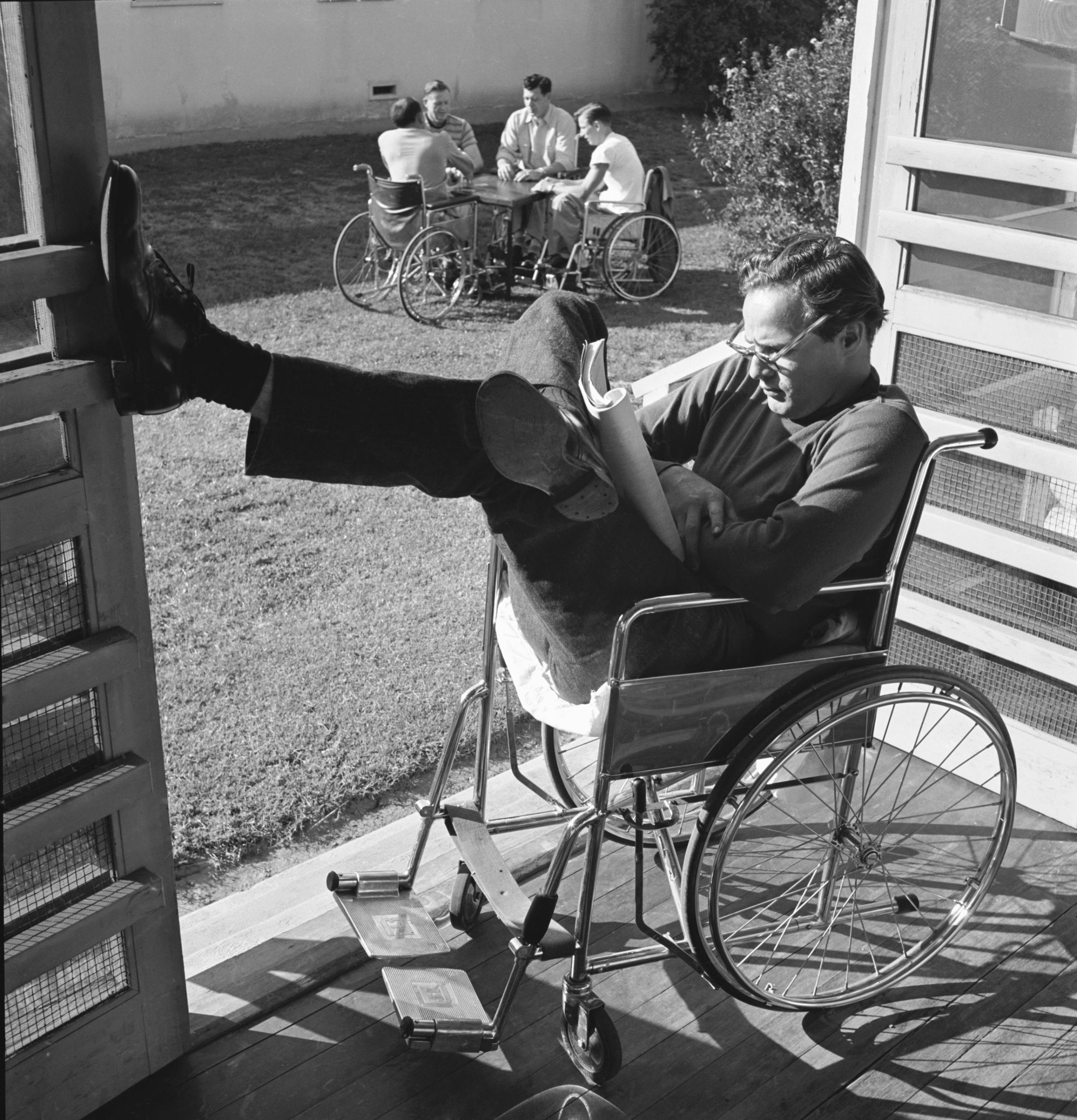

Photographer Ed Clark captured Brando’s explosive arrival in California, chronicling the actor as he submerged himself in “The Method” — e.g., taking to a wheelchair and struggling with leg braces while living among paraplegics at a VA hospital in Van Nuys. But Clark also came away with surprising glimpses into the more personal, private Brando.

Here, on the 10th anniversary of Brando’s death (the Omaha, Neb., native died on July 1, 2004, in Los Angeles), LIFE.com presents a number of Clark’s photos — most of which were never published in LIFE — at a time when the actor was just beginning to forge his own Hollywood legend.

Accompanying Ed Clark’s images in LIFE’s archives were meticulous notes about Brando written by Theodore Strauss, who would ultimately write the magazine’s 1950 profile that coincided with the release of The Men. Strauss details the actor’s every eccentricity: what he wore, how he ate, what he read, how he shunned any sort of red carpet that might have been laid out for him when he came to town.

“Stanley Kramer, producer of The Men, had intended on putting Brando in a good hotel, but Brando would have none of it,” Strauss wrote. “First of all he insisted on living with the paraplegics in Birmingham Veterans Hospital during the four weeks before production began. This, he felt, was necessary to giving a completely knowledgeable and valid performance in his role. He was given a bed in a 32-bed ward, where he was treated almost like any other patient.”

The actor’s reputation as a bad boy had preceded him, stories of his nose-picking, shabby dress, foul language and grumbling interviews having traveled all the way from New York to Los Angeles. But, LIFE wrote, “however infantile or irresponsible Brando may be in his personal life, he is a totally conscientious artist in his work. Unlike some of Hollywood’s pretty people, he was never late on the set, never indulged in a tantrum, never required endless retakes.”

He was also far more of an introvert, in some ways, than his reputation suggested. Brando, wrote Strauss, “reads everything, absolutely omnivorous — from Krishnamurti to recent novels.” For the actor, it was all about the craft — nothing else, even life’s essentials, seemed to matter. From LIFE’s profile: “His salary, for the soundest of reasons, has been sent to his father, Marlon Brando Sr., who invests the money in cattle on a Midwestern ranch called Penny Poke. Each week Brando receives a living allowance of $150. Because he rarely looks at money and sometimes pays for a package of cigarets with a $20 bill, he usually is penniless by the second day.”

Of his relationship with the real paraplegics and quadriplegics from whom he was learning for his role, Strauss noted that “Brando’s orientation and adjustment as a paraplegic was so complete that he participated in their sometimes gruesome horseplay with complete freedom — one of the reasons why he was so completely accepted. [Pranks] include pillow fights and using hypodermic syringes for water pistols.”

From Strauss’ notes about Hollywood’s reaction to Brando: “Thus far no one has accused him of posing; everyone to whom we’ve spoken has a sort of confused respect for a man who, up to now, has managed to live as he feels, without caring a hoot what anyone thinks.”

In his personal style, meanwhile, the actor was unfussy and unpretentious, almost to a fault: “When Brando first arrived in Hollywood his only luggage was a battered, imitation-leather suitcase the size of a woman’s overnight bag,” Strauss observed. “He was wearing a blue worsted suit which had seen much wear and weather — there were holes and tears in the jacket, and a part of Brando was visible through the seat of the pants.”

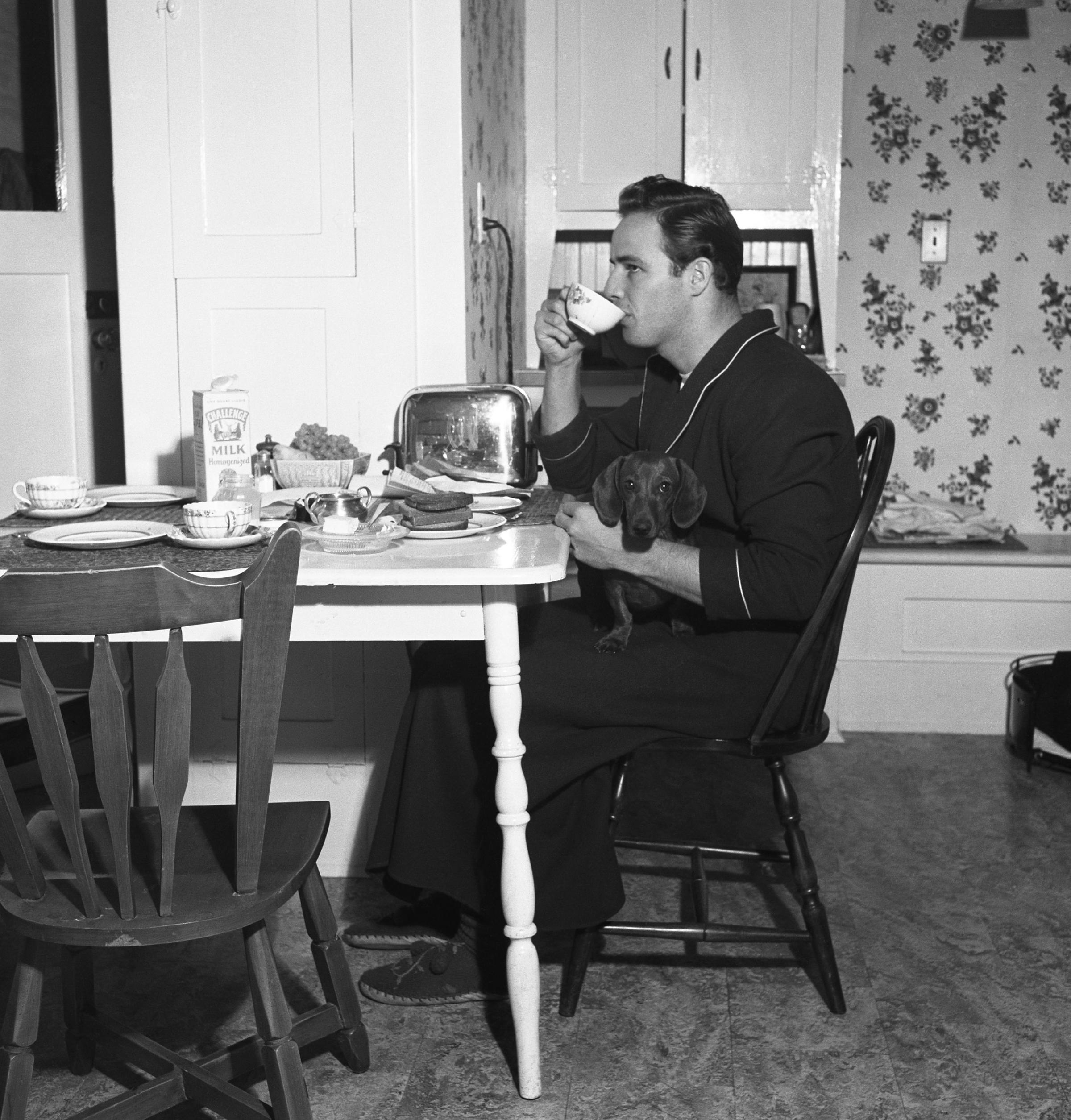

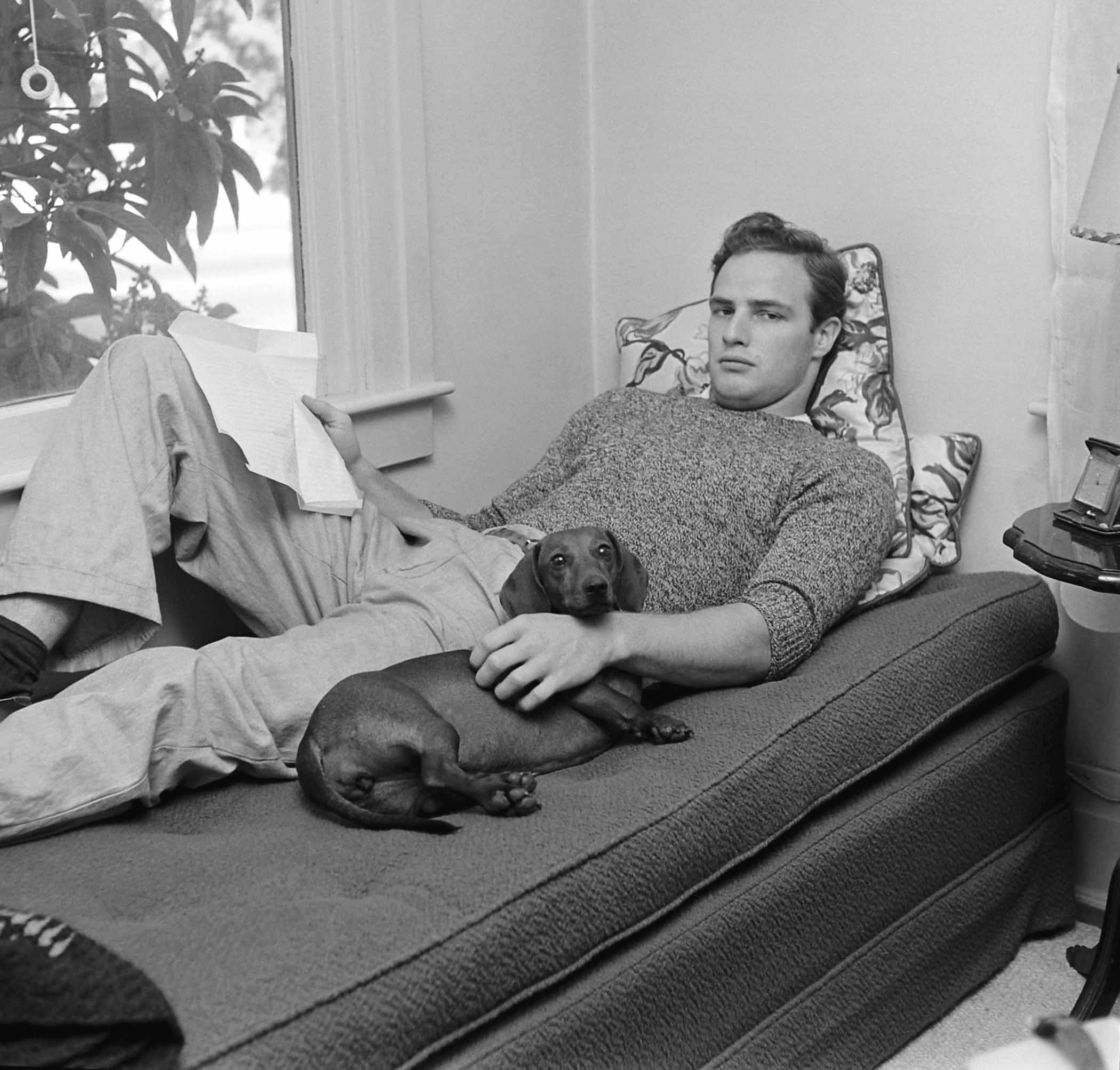

Once official production on The Men began, Brando moved out of the veterans hospital and into a small bungalow owned by his aunt, Betty Lindemeyer, in Eagle Rock, Calif. During this period Brando’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Myers, was also a house guest.

“She [his grandmother] was quite abashed because Ed Clark took pictures of Marlon in a bathrobe, which happens to be hers,” reported a production assistant in notes found in LIFE’s archives. Grandma Myers was also apologetic about the barbaric way her grandson ate: “Bud doesn’t bring the food to his face,” she told LIFE, using Brando’s nickname. “He brings his face to the food.”

“I do hope that Bud comes through all this without too much scandal,” she confided to LIFE at one point. “I love him more than anything on this earth, but I never know when I’m going to hear from him in San Quentin.”

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com