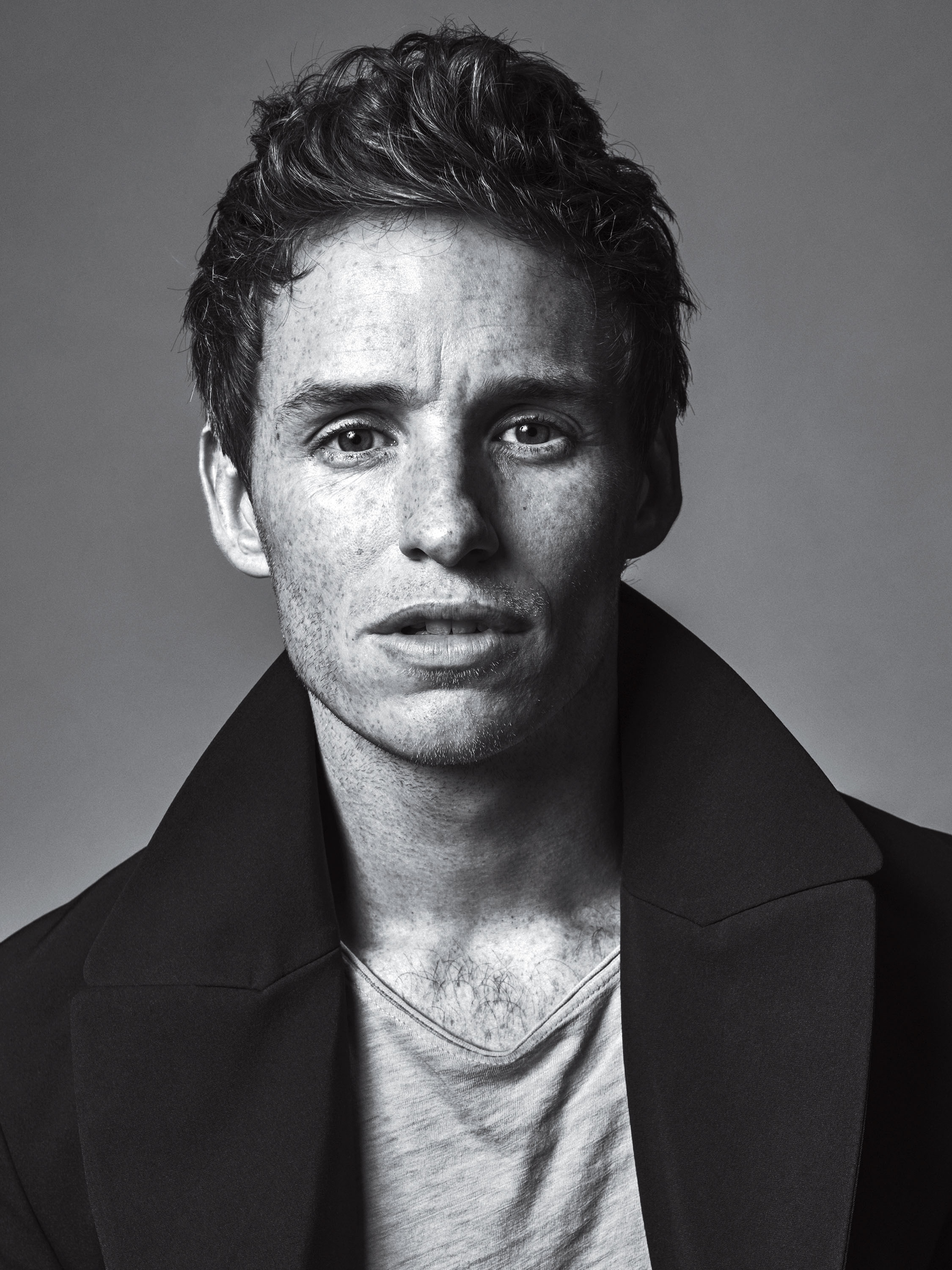

There’s a muscle throbbing in Eddie Redmayne’s cheek, just under his right eye, a muscle most people don’t even know they can control. It pops out, bulbous, even as the rest of his freckled face stays still. Then Redmayne relaxes it. It looks like an impressive party trick, but it’s more than that. “Stephen Hawking can only use this muscle to communicate,” he says.

Redmayne practiced contracting that muscle for months to play Hawking in The Theory of Everything, in theaters Nov. 7. The biopic begins with the renowned physicist’s early years, when he meets his first wife Jane (Felicity Jones). They quickly marry after Hawking–then 21 and studying cosmology at the University of Cambridge–is diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease) and given just two years to live. It isn’t a film so much about Hawking’s fabled contributions to physics as his poignant and tangled personal life. His marriage turns rocky as Jane struggles for the next 25 years to raise three children and care for her husband, who is slowly losing control of (almost) every muscle in his body.

This wasn’t the first time Redmayne, 32, was enveloped by a role. While playing artist Mark Rothko’s assistant in the 2010 play Red, he took up painting–despite being color-blind. After winning a featured actor Tony for Red and starring opposite Michelle Williams in the critical darling My Week With Marilyn, Redmayne got his big break as Cosette’s suitor Marius in the 2012 film adaptation of the musical Les Misérables. Rumors swirled about which superhero he would get to play for his next role. “The reality is, I tried really hard to be the baddie in The Amazing Spider-Man 2,” he says, “and totally failed.”

Instead of a blockbuster, he landed a role in this far quieter film, and it works in his favor. Redmayne has mastered the glint of the eye that conveys a mind constantly at work, even if his body can’t be–a maneuver that he picked up from Hawking himself. “In life, generally, silence is powerful. But you’re also trying to read every minutia of his expression,” he says. “He commands a room.”

At 72, Hawking is now confined to a wheelchair and can communicate only through a computer. He moves the same cheek muscle Redmayne can isolate to tell a cursor when to stop over a particular letter on the keyboard. When a full sentence is formed, the computer speaks it. That made Redmayne’s only meeting with Hawking tricky. “In the three hours I spent with him, he said maybe eight sentences,” says Redmayne. “I just didn’t feel like I could ask him intimate things.”

So he found other ways to prepare. He trained for four months with a dancer to learn how to control his body. He stood in front of a mirror for hours, contorting his face. He kept a chart tracking the order in which Hawking’s muscles declined. He met with 40 ALS patients. He lost about 15 lb. (7 kg). He remained hunched over and motionless between takes, so much so that an osteopath told him he had altered the alignment of his spine. “I fear I’m a bit of a control freak,” he says. “I was obsessive. I’m not sure it was healthy.”

Redmayne never trained as an actor, a fact he mentions often. Instead, he compensates with manic perfectionism. Sitting in a New York City hotel room months after wrapping, he’s eager to show off the minute details of his physical performance. He leaps off the couch and searches frantically for a pen to demonstrate how Hawking’s grip changed over the years. Finally settling for a knife, he becomes self-conscious: “I don’t know why I’m …” he mumbles, his boyish face turning pink. “It’s such a tiny thing.” He spends several minutes mimicking the slow deterioration of a hand, his fingers contorting in different directions and the joints seizing up. Though the movements are natural for him by now, they’re also strenuous. Afterward, he collapses back onto the couch, his body loosening like a dropped marionette.

On the set, Redmayne felt a perpetual sense of anxiety trying to capture that subtlety. “I don’t know if I ever actively enjoyed it,” he says. “After doing all this research, Stephen had reached idol status for me. I desperately wanted his approval. Fear drove me.” Only after Hawking declared the performance “broadly true” and granted the filmmakers permission to use his copyrighted computer voice in the movie did Redmayne feel truly at ease.

Though Hawking may have been the only critic that mattered to Redmayne, the performance also earned him Oscar buzz at the Toronto Film Festival. In the awards race, critics have pitted Redmayne against Benedict Cumberbatch, who plays another British master of science, Alan Turing, in the upcoming biopic The Imitation Game.

Because Cumberbatch also played Hawking (in a British TV movie) and both actors have dedicated followings– Redmayniacs vs. Cumberbitches–some believe they have a rivalry. Redmayne dismisses the idea. “I feel like my named following was written in reaction to Ben’s,” he says, laughing. In fact, the two are old buddies. When Redmayne was filming at Cumberbatch’s old boarding school, he found an award labeled “B. Cumberbatch.” He took a selfie dressed as Hawking in front of it and sent it to his friend.

Such moments of levity were essential during the grueling shoot. Playing Hawking may have bent Redmayne’s spine, but it also taught him to ease his nerves. “I get caught up in the foibles of everyday life,” he says. “But playing Stephen was a constant reminder to put things in perspective: we only have one chance at this.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com